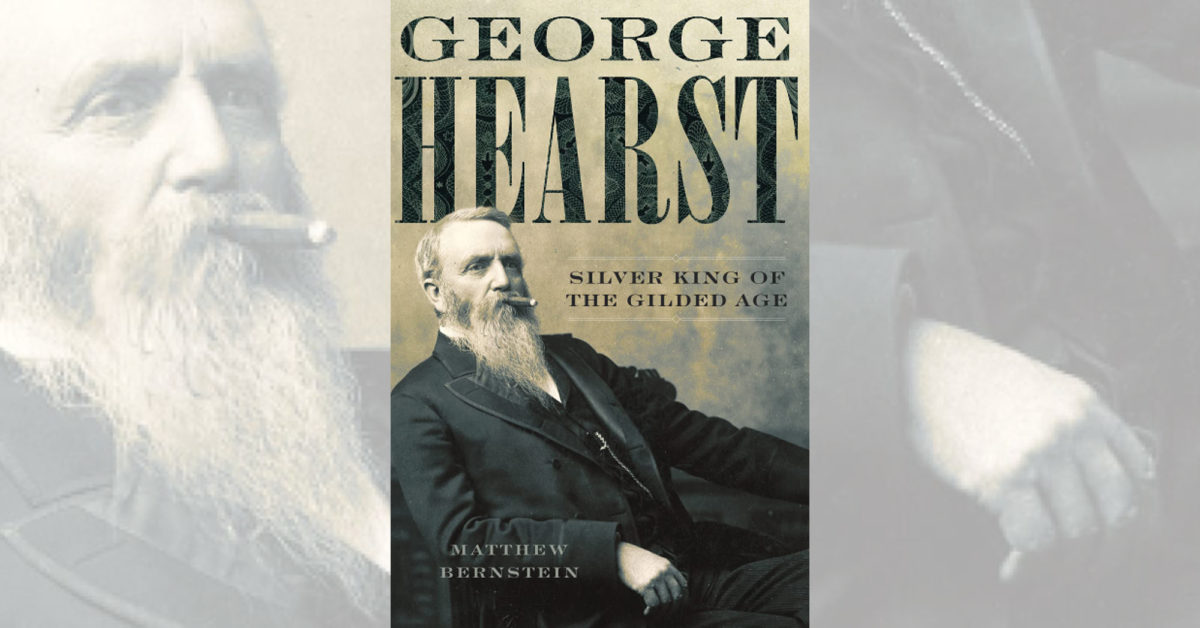

George Hearst: Silver King of the Gilded Age, by Matthew Bernstein, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2021, $55

Americans who do recognize his name likely recall George Hearst as the father of infamous newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, in no small part because Orson Welles related the younger Hearst’s quasi-biographical story in the 1941 drama Citizen Kane. But father Hearst was himself a self-made, larger-than-life figure who, as author Matthew Bernstein notes in this first-rate biography, “filled the bill as the quintessential American prospector, full of piss and vinegar and with a nose for gold.”

In the 21st century Hearst also claimed a share of film fame, as a character in the HBO series Deadwood—but not the kind of attention he would have wanted. As portrayed by Gerald McRaney, George was a vicious sociopath who would stop at nothing to gain control of the largest gold mine in the Black Hills. The real Hearst was hardly bloodthirsty, though he did make a killing in Deadwood. Indeed, he very cleverly gained control of the valuable Homestake Mine by first shutting it down to give the false impression it was a bust. “Hearst,” writes Bernstein, “demonstrated for good and all that in the great game of pay dirt he was second to none.”

The Missouri-born Hearst ventured west from his native state in 1850 to join the California Gold Rush and had little initial luck at placer mining and locating quartz veins, earning him the nickname “Quartz George.” In 1859, however, he hit it big silver mining in what was then western Utah Territory but would become Nevada’s Comstock Lode. “I got to the Comstock and in six months made half a million dollars,” he bragged. He later mined silver in the Tough Nut Lode outside Tombstone, Arizona Territory, owned the prosperous Ontario Mine near Salt Lake City and operated the Anaconda Mine in Montana Territory. He was a risk-taker in an endless quest to increase his holdings, and he didn’t limit himself to mining. He engaged in cattle ranching in California, New Mexico and Mexico, owned a thoroughbred horse racing stable and entered the political arena with mixed success. In 1882 he ran unsuccessfully as the Democratic candidate for governor of California but twice served as a U.S. senator (appointed the first time to fill a vacancy due to a death, but elected the second time, serving from March 4, 1887, until his own death at age 70 on Feb. 28, 1891, in Washington, D.C.).

While making and losing fortunes and then making them again, Hearst was happy to wear worn clothes and eat unpretentious meals, although his much younger wife, Phoebe, liked to give parties, live in style and travel the world with their beloved and somewhat rambunctious son, William Randolph, who in 1887 would take over management of his father’s newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner.

While Phoebe championed such progressive notions as women’s rights and education reform, George had a record of voting against emancipation, Chinese emigration and women’s suffrage. “Such torpid beliefs stemming from an active mind are understandable when one considers that Hearst’s focus had been mainly in acquiring capital, not in spending it,” the author suggests. “He would leave that part of the Hearst saga to his wife and son.”

One thing is clear from this first-full-length biography of George Hearst, the man had his share of human flaws and was complex. He certainly had the energy to keep pushing to succeed. Bernstein does his research and writes well, although a reader might have trouble trying to keep track of George’s wheeling and dealing across the American West. The author is a regular contributor to Wild West, and he adapted sections of the book for the feature articles “Murder in the Black Hills” (December 2018) and “The Playwright Who Captured Geronimo” (December 2019).

George Hearst

Silver King of the Gilded Age

By Matthew Bernstein

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.