In the summer of 1940 the Second World War had been under way for nearly a year. Hitler’s Germany was triumphant. The United States was neutral. It was a time, Winston Churchill later observed, when “the British people held the fort alone till those who hitherto had been half blind were half ready.” Some Americans, however, did not remain on the sidelines.

That summer and fall, eight American pilots fought against the Nazis in the Battle of Britain. This remarkable bunch of rogue flyers included ex-barnstormers, a Minnesota farm boy, and the greatest bobsled champion in American Olympic history. All had defied strict neutrality laws—thereby risking loss of their citizenship and imprisonment if they dared return home—in order to join what they regarded as the best flying club in the world: Britain’s Royal Air Force.

With only minimal training, they dueled with some of the Luftwaffe’s finest aces in the greatest man-on-man contest in the history of aviation and, by October 1940, had helped save England from Nazi invasion. Dozens more Americans soon joined them, enough to fill three squadrons—all of this months before Pearl Harbor marked America’s belated entry into the Second World War.

The first American to enlist in the RAF during World War II was no ordinary American. Twenty-nine-year-old Billy Fiske was one of the most remarkable sportsmen in Olympic history. He spent much of his adolescence in Europe, graduated from Cambridge University, and went on to work as a banker in London and New York. In his spare time, he completed the Le Mans 24-hour auto race when he was only 19 and earned the unofficial title “The King of Speed” by dominating bobsledding between the wars. In 1928, Fiske became, at age 16, the youngest-ever winner of a Winter Olympics gold medal for the bobsled. In 1932, at the Lake Placid Winter Games, he carried the Stars and Stripes for the Americans at the opening ceremonies, presided over by Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York.

At the outbreak of war in September 1939, Fiske decided he would pretend to be a Canadian in order to circumvent American neutrality laws. Before an interview with an RAF recruiter, he played a round of golf to give himself a “healthy look.” In his diary he wrote, “Needless to say, for once, I had a quiet Saturday night—I didn’t want to have eyes looking like blood-stained oysters the next day.” Fiske’s interviewer was impressed and recommended he be sent to the RAF No. 10 Elementary Flying School. Fiske duly pledged his life and loyalty to the king, George VI, and was formally admitted into the RAF. In his diary, a joyous Fiske wrote, “I believe I can lay claim to being the first U.S. citizen to join the RAF in England after the outbreak of hostilities.”

Three other Americans were admitted into the RAF shortly after Fiske: Andy Mamedoff, Eugene Tobin, and Vernon Keough. The 23-year-old Tobin and 27-year-old Mamedoff had been flying friends at Mines Field in California, now Los Angeles International Airport, before the war. Tall, red-haired Tobin had paid for flying lessons in the late 1930s by working as a guide and messenger at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film studio. Mamedoff had grown up in Thompson, Connecticut, where his White Russian family had settled in the early 1920s. Both were convinced that the war in Europe would come to America sooner or later, and they didn’t want to be drafted into the army as grunts when it did.

Above all, they were looking to fly the “sweetest little ship” in the world, the Supermarine Spitfire, designed by Englishman R. J. Mitchell, first flown in 1936, and now capable of over 350 mph, three times faster than any plane they had flown. “I just felt I wanted to fly some of these powerful machines,” Tobin recalled. But only by risking their necks in someone else’s war would they get that chance. The gamble seemed well worth it.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

In May 1940, Tobin and Mamedoff had braved the U-boat threat and crossed the Atlantic in a convoy with the smallest man ever to fly in the RAF’s dark blue uniform: 4 foot 10 inch Vernon Keough, 28, who had introduced himself to his fellow American adventurers as “Shorty.” A stunt pilot, Keough was one of America’s first professional skydivers. At fairs and air shows around New York, he had jumped out of biplanes more than 500 times.

In early July 1940, the three pilots were assigned to 609 Squadron at Middle Wallop airfield in southern England, where they were quickly accepted as honorary Brits. To the young British pilots, the lanky and wisecracking “Red” Tobin seemed like a cowboy out of a Hollywood movie. The charming and roguish Andy Mamedoff loved to gamble and wagered small fortunes on games of bridge; between scrambles, he also taught the Brits in the squadron how to play stud and Red Dog poker. Shorty earned plenty of laughs as he ran to his Spitfire on practice scrambles, a cushion under each arm; he needed to sit on two to see out of the plane’s cockpit.

If it was action the Americans were looking for, they could not have arrived in England at a better time. Just days after the men reached their frontline squadron, on July 10, 1940, the Luftwaffe opened a daylight bombing campaign against Britain. The Battle of Britain was on.

Two days later, Billy Fiske was posted to 601 (County of London) Auxiliary Air Force Squadron at Tangmere, on England’s south coast. Also known as the Millionaires’ Squadron, it had been composed since the 1920s of mostly wealthy aristocrats, recruited at the elite gentleman’s club, White’s, by Lord Edward Grosvenor.

There was some apprehension in 601 about “the untried American adventurer,” according to the squadron’s official record book. But Fiske made no pretensions about his flying skill and was soon popular with the squadron’s other flamboyant and daring pilots. When not on duty, he invariably beat them in races to local golf courses and pubs in his 4.5 liter open Bentley, painted British racing green, complete with bonnet strap and projecting supercharger.

On July 20, Fiske flew for the first time in a 601 plane, making two patrols. Over the coming weeks, he would fly with the same exceptional skill that he guided bobsleds, pushing his plane to its operational limits without being reckless. When the call to scramble sounded, Fiske was often first to sprint to his “kite,” so eager was he to test himself in the ultimate thrill ride.

Aside from Fiske and the American trio in 609 Squadron, four other American citizens served in the RAF during the Battle of Britain. Twenty-eight-year-old Philip Leckrone, from Salem, Illinois, flew more than two dozen sorties over the English Channel as a “tail-end Charlie”—the rear plane in a formation—in 616 Squadron. Minnesotan Art Donahue, 27, was perhaps the most experienced of all the Americans who flew in the RAF during the summer of 1940, having logged over 1,000 hours in the air before joining. He was posted to 64 Squadron just six weeks after leaving his farm in St. Charles, Minnesota. The very next day he destroyed his first bandit: a Bf 109. But then, barely a week later, he was shot down, his face and hands severely burned. He would spend the rest of the Battle of Britain recuperating. (And was shot down over the English Channel two years later, his body never found.)

Pilot Officer Hugh Reilley, who had been born in Detroit, Michigan, served with 66 Squadron. It was only after he had been shot down and killed by the legendary German ace, Werner Molders, that RAF personnel discovered that Reilley, who had passed himself off as a Canadian, was in fact an American citizen. His squadron leader recalled that when Reilley was buried, the families of dockhands in the riverside town where the squadron was based lined the streets and graveyard “in large numbers to pay their respects as the cortege went by.”

According to RAF rosters of the period, the only other American known to have served during the battle was 19-year-old John K. Haviland from Mount Kisco, New York, the son of an American navy officer and English mother. Haviland was one of many green pilots brought into decimated squadrons that summer; pilots who had not even practiced deflection shooting and had less than 20 hours on fighters. Raw and scared, many crashed their planes and died or were wounded in accidents rather than combat. This was the case with Haviland, who collided with another Hurricane during formation practice the very day after he joined 151 Squadron. Thankfully, he was able to bring his Hurricane down in a paddock; he would see no further significant action in the Battle of Britain.

On August 13, 1940, the Luftwaffe launched its first all-out mass attack, codenamed Eagle Day. More than 50 Stuka dive-bombers attacked airdromes in the area of Portland naval base on England’s south coast. Spitfires of 609 Squadron shot down five enemy planes for a record haul. Above the English Channel, 601’s Billy Fiske shot up a German bandit’s underbelly but was unable to claim the kill because he did not see the German crash or burst into flames.

Three days later, on August 16, the Luftwaffe singled out Fiske’s base at Tangmere for attack. RAF Fighter Command ordered 601 to patrol over Tangmere at about 12,000 feet: Ju 87 dive-bombers had been detected as they crossed the English coast at nearby Selsey Bill. Soon, the Stukas started to dive on Tangmere, killing several ground staff and badly damaging the airfields. Fiske and his fellow 601 pilots chased the Germans out to sea just to the south around Pagham Harbor and downed several enemy planes.

Then someone spotted Fiske’s Hurricane returning to the base. It was badly damaged and was seen to “glide over the boundary and land on its belly.” Medical and fire crews rushed to the plane. The squadron’s operations record book recorded what happened next: “Pilot officer Fiske was seen to land on the aerodrome and his aircraft immediately caught fire. He was taken from the machine but sustained severe burns….”

Fiske was rushed to the Royal West Sussex Hospital in Chichester but died the following morning from shock. He was just 29, the first American pilot to be killed during the Battle of Britain.

There was no time to grieve. The battle grew more intense with each unusually hot summer day. On August 18, 1940, the Germans again attempted to finish off the RAF by launching a massive air attack that hammered British defensive installations, radar towers, and airfields. RAF Fighter Command flew nearly 1,000 sorties, sending all available squadrons into battle, including 609 Squadron. Mamedoff, Tobin, and Keough saw action for the first time.

Recommended for you

Tobin fired 2,000 rounds and burned through 80 gallons of fuel but allowed his target, a Bf 110, to escape. Keough’s first round with the Germans was just as frustrating. He fired his Browning guns repeatedly at the enemy but could not take a bandit down, probably because like many novices he did not get close enough to his target. Mamedoff also returned empty-handed.

Two days later, on August 20, six members of Tangmere’s ground staff carried Billy Fiske to his final resting place. As his coffin, covered in the Union Jack and the Stars and Stripes, was borne on a bier to Boxgrove Priory Church, the RAF’s Central Band played funeral marches. Buglers gave the “supreme artist of the run” a farewell, and then a rifle squad cracked the silence with a salute. Up above, Fiske’s English comrades fended off yet more Stuka attacks as the Battle of Britain raged on. By now, the RAF was fast running out of pilots. If the Luftwaffe continued bombing air bases and radar installations, the battle would soon be lost.

On the day of Fiske’s funeral, Red Tobin attacked a group of Bf 110 fighters escorting Junkers 88 bombers and badly damaged two of them. The following day, August 24, cannon shells and machine gun bullets of a German fighter smashed the tail wheel of Andy Mamedoff’s Spitfire and pierced the plane’s armor plating and seat. Mamedoff managed to land safely, miraculously uninjured except for bruising on his back. Like many other tail-end Charlies that summer, Mamedoff had been so busy watching out for his comrades flying ahead of him that he had neglected to watch his own back, and had been taken completely by surprise.

That evening, in a local pub, Tobin commiserated with him. “For a week after, Andy looked like the Hunchback of Notre Dame,” Tobin later wrote. “It was Andy’s birthday so we drank to the present he’d received from the Krupp [arms] factory.”

Day after day that late summer, the pilots fighting for Britain engaged in dogfights above England and the Channel, vapor trails crisscrossing the perfect blue skies. As more and more were shot down, the Americans—and pilots from other nations who’d joined the RAF—became indispensable. Indeed, every man in a cockpit counted. But how much longer could they hold out as Hitler threw the full might of the Luftwaffe against them?

At dawn on September 7, 1940, the Germans sent aloft the largest grouping of attack aircraft in history. In the first major attack on London itself, 1,012 German aircraft struck at its heart, setting the city and its docks ablaze, killing more than 400 people, and injuring over a thousand. The Blitz had begun and would continue unabated for the next four months.

Ironically, the Luftwaffe’s shift of attack from airdromes and radar stations to London meant the RAF was saved from destruction. Had the Luftwaffe persisted in destroying the RAF’s infrastructure, victory would have been assured. In ordering his air force to strike at a civilian target, Hitler had made his first great strategic mistake of the war.

On September 15, the Germans again sent more than 1,000 planes across the Channel, again headed for London, aiming to terrorize the British into submission and deal a knockout blow to the RAF’s Fighter Command. The battle’s climax had arrived. The American pilots were in top form, playing their part in the most crucial day of air combat in history. Tobin shot down a Dornier bomber and probably destroyed a Bf 109. Fellow 609 pilots Mamedoff and Keough also fought with enormous courage and stamina, claiming kills of their own.

It was a black day for the Luftwaffe. The combined losses to Hitler’s air force were so punishing that the usual flocks of German bandits did not return the following day. The Germans could not sustain such losses and were no nearer, after three months of hard pounding, to controlling the air space above the English Channel and southern England—Hitler’s stated precondition for launching the amphibious invasion of England called Operation Sea Lion.

On September 17, Grand Admiral Raeder recorded in the official German war diary: “The enemy air force is by no means defeated. On the contrary, it shows increasing activity.” And then the all-important words: “The Führer therefore decides to postpone Operation Sea Lion indefinitely.” Britain would not be invaded. Instead it would be brought to its knees through terror bombing at night and slow starvation by day. What was left of the Luftwaffe’s bomber fleet and the now more-important Atlantic U-boat packs would sooner or later surely see to that. Besides, Hitler now nursed a greater design than the humiliation of Winston Churchill: the conquest of Soviet Russia. “I want colonies I can walk to without getting my feet wet,” he would soon tell one of his confidantes.

It was not yet clear to Churchill’s fighter boys that they had fought off the greatest threat to Britain’s survival in a millennium, and had done so by, in Churchill’s words, the “narrowest of margins.” On September 15 they had made possible a far greater victory. As an official RAF historian would write, “When the details of the fighting grow dim, and the names of its heroes are forgotten, men will still remember that civilization was saved by a thousand British boys.”

And a few Americans.

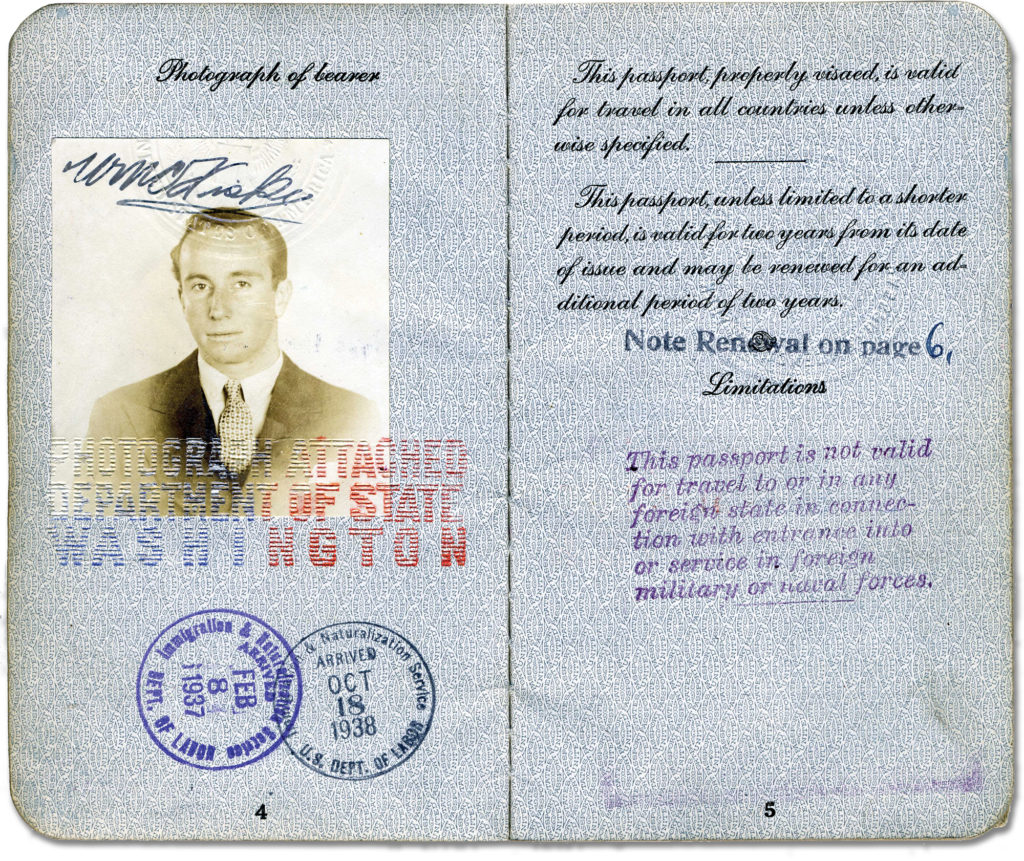

Four days after the climax of the Battle of Britain—on September 19, 1940—Red Tobin, Andy Mamedoff, and Shorty Keough became the first Americans to join the new 71 “Eagle” Squadron, the first all-American unit in RAF history. Five months earlier, an influential London-based American banker, Charles Sweeny, had contacted Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Aircraft Production, with the idea of an all-American squadron, whose shoulder patch would resemble the insignia of the eagle on his American passport. Beaverbrook, whose son, Max Aitken, had at the time been 601’s squadron leader, had liked the idea and had recommended that Sweeny contact Brendan Bracken, personal assistant to Winston Churchill. Bracken was an old friend of the Sweeny family and had quickly forwarded the idea to Churchill, who was immediately enthusiastic.

The potential for positive propaganda was unrivaled. Here were America’s finest young airmen, ready to lay their lives on the line for democracy while their own country slept. An all-American squadron flying in the RAF would powerfully and symbolically undermine the notion of American neutrality.

By the fall of 1940, dozens of Americans, inspired by the widely reported exploits of RAF pilots that summer, were defying American neutrality laws and making their way to Britain. (In 1941, as the first Eagle squadron garnered hugely favorable publicity in the United States, the State Department decided not to prosecute any of the American pilots in the RAF, no doubt for fear of a public outcry but also because isolationist sentiment in the United States was waning.)

The 71 Squadron first saw active duty on January 4, 1941. The following day, Shorty Keough was flying in close formation at 20,000 feet with two fellow 71 recruits, pilot officers Edwin Orbison and Philip Leckrone. Suddenly, Orbisonand Leckrone collided. Orbison was able to turn back toward their base. Leckrone went into a tail-spin and plunged toward the ground.

Keough followed Leckrone down, shouting at him over the radio telephone.

“Bail out! Bail out!”

Leckrone did not reply and made no attempt to bail out. He died on impact. Orbison landed safely despite a damaged left wing. According to the squadron’s operations book, Leckrone had joined the RAF “for the highest of motives—not for the glamour, if any, or the thrills, but to defend our way of life.” He was buried the next day, the first fatality in 71 Squadron.

There would be many more. Indeed, sooner or later the odds caught up with all but a very fortunate few. During a patrol on February 15, 1941, Shorty Keough failed to return from a scramble. Several hours later, a coast guard unit found a pair of size five flying boots floating amid wreckage in the Channel. “Nobody but little Shorty could wear such small boots,” reported 71 Squadron’s operations record book. “There can be little doubt that Shorty’s plane dived into the sea at great speed and that he was killed instantly.”

Nonetheless, by the spring of 1941, so many American pilots had made it to Britain, eager to do their part, that the RAF was able to form a further two Eagle squadrons, 121 and 133. Later that summer, Andy Mamedoff was selected to lead a flight in 133 Squadron, the first American to be so honored.

Shortly before leaving for his new assignment, he also became the first of the Americans to take a war bride: Penny Craven, a member of the hugely wealthy Craven cigarette family. Fellow American pilot Vic Bono arranged for a flyby a few minutes after the wedding in Epping. Unfortunately, it was market day and the low-flying pilots sent pigs and cows scuttling in all directions, leaving the marketplace a wreck.

On September 7, 1941, Red Tobin joined 15 pilots from 71 Squadron in a sweep over northern France. Around 75 miles inland, radar announced the presence of bandits to their rear, between them and the Channel. The bandits turned out to be 100 Bf 109s that had waited for the RAF planes to fly inland. Squadron leader Stanley Meares suddenly shouted over the radio, “Every man for himself now, chaps.”

The 109s attacked the Spitfires from above, at 29,000 feet, and then returned to higher altitude and attacked again. Two 71 Squadron pilots were killed, including Tobin, and three had to bail out.

In early October, Andy Mamedoff learned that his new unit, 133 Squadron, would be posted to Northern Ireland. On October 8, in atrocious weather, he and his flight of 15 pilots left for their new posting. All reached their first refueling stop at Sealand, a sea fort off the coast of England. Then the weather closed in. Only six pilots made it to next refueling stop on the Isle of Man. Three landed elsewhere, two turned back to Sealand, and four died; they included flight leader Andy Mamedoff, whose Hurricane had suddenly plummeted onto a field on the Isle.

In December 1941, two years after Mamedoff had left America, his countrymen finally joined the Second World War following the attack on Pearl Harbor. The following September, all three Eagle Squadrons were folded into the U.S. Army Air Forces, becoming the 4th Fighter Group. The group would eventually destroy more than 1,000 enemy aircraft. That success was based on tactics first learned in the RAF by the few Americans who, ironically, ended up helping the United States by breaking its laws in the summer of 1940.

Only one of the American pilots who flew in the Battle of Britain managed to survive the war. After flying Mosquito dive-bombers and Blenheims, John Haviland returned to Spitfires in late 1944 and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross as a flight lieutenant with 141 Squadron on February 16, 1945. At war’s end, he returned to the United States, went back to college on the GI Bill, and never left: he retired as a distinguished Professor of Aeronautics at the University of Virginia in the 1980s. Haviland raised five children and continued to fly almost to the day he died in July 2002. A scholarship foundation for aeronautics students has since been established in his name at the University of Virginia.

In 1940, Winston Churchill famously said of the pilots who had fought for Britain, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” Today, fewer and fewer of the “few” remain. As a result, perhaps, the significance of the greatest air battle in history has been downplayed. Many Americans do not realize that had it not been for the few, the Second World War would have had a very different outcome.

And to this day, even in England, the role played by foreign-born pilots tends to be overlooked. Indeed, it is generally assumed that the British fought alone during the summer of 1940. But on the RAF’s Runnymede Memorial, and in many other corners of England, there are many tragic reminders that this was not, in fact, the case. A fifth of the few came from foreign shores, mainly Poland, New Zealand, Canada, and Czechoslovakia. Of these 510 pilots, more than a quarter never returned home.

On July 4 of most years, in a corner of Boxgrove graveyard in Sussex, fresh flowers lie on the grave of one of these foreigners: Pilot Officer Billy Fiske, the first American to die in the Battle of Britain. “The King of Speed” lies between two British soldiers, a sapper in the Royal Engineers and a corporal in the East Lancashire Regiment. A small American flag sometimes snaps in the wind above his final resting place. On his headstone the following words are inscribed for all to see:

He died for England

Alex Kershaw is the bestselling author of six acclaimed books, five of them about World War II. His grandfather served in Egypt in the RAF during the war. His 2006 book, The Few, was selected as the Military Book Club’s first-ever book of the year. His 2008 book, Escape from the Deep, is currently being adapted for the screen.