In September 1939, as war winds buffeted Europe, Americans watched warily while the German blitzkrieg swept across Poland. Despite the United States’ official policy of neutrality, many realized it was just a matter of time before America was drawn into the conflict, especially after the invasion of France and the Low Countries in May 1940 made Nazi intentions clear.

Some Americans, not wanting to wait for an official declaration of war, sought to enlist wherever they could. To young pilots and would-be airmen, the early tales of aerial battles lent a romantic allure to combat flying. Adding to the excitement was the recent development of sleek new fighter aircraft such as the Supermarine Spitfire, capable of flying at well over 350 mph.

As Britain’s Royal Air Force faced off against Germany’s Luftwaffe, the need for competent pilots became increasingly apparent. Famed World War I Canadian ace Billy Bishop suggested that recruiters look to the United States for a promising source of new pilots and air crewmen. Despite the unfavorable legal climate created by America’s Neutrality Acts, the Clayton Knight Committee was set up to recruit pretty much anyone who was interested in flying.

Clayton Knight was a World War I pilot veteran with connections, and along with Bishop and another WWI pilot, Homer Smith, he worked out a recruiting plan. Knight approached the chief of the U.S. Army Air Corps, Maj. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, who was happy to supply a list of recent Air Corps washouts—the first targets of the recruiting efforts. Many possessed good flying skills but were a little too unruly for the Army Air Corps. About 300 were signed up by May 1940. Eventually more recruiters spread out across the country, seeking volunteers with some aviation experience. The new recruits were actually signing up with the Dominion Aeronautical Association, a supposed civil aeronautics firm that just happened to have its main office located next-door to the Royal Canadian Air Force headquarters in Ottawa. By the fall of 1941, more than 3,000 Americans had been successfully recruited, and by the end of the year that number had swelled to 6,700.

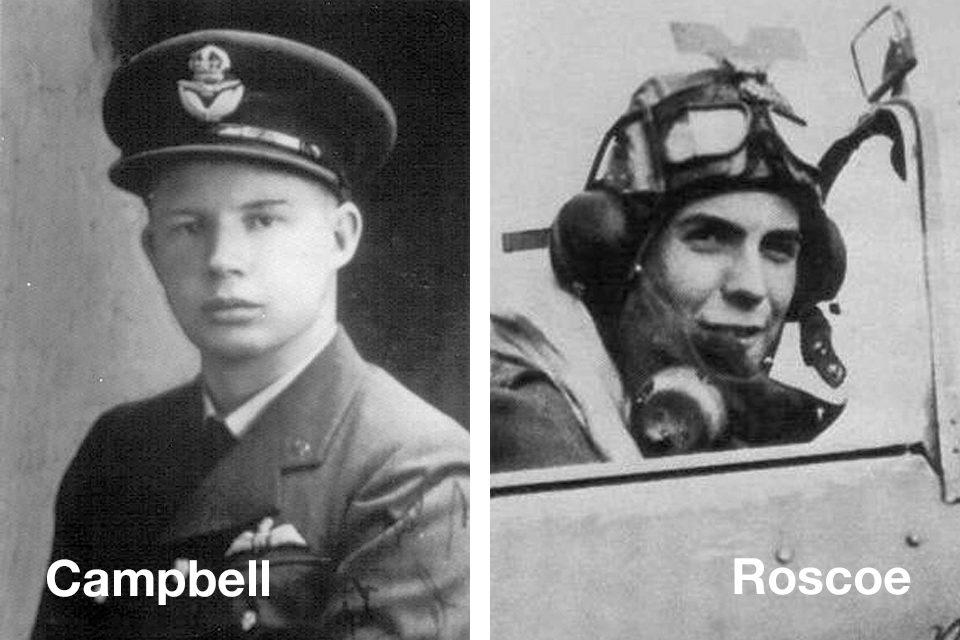

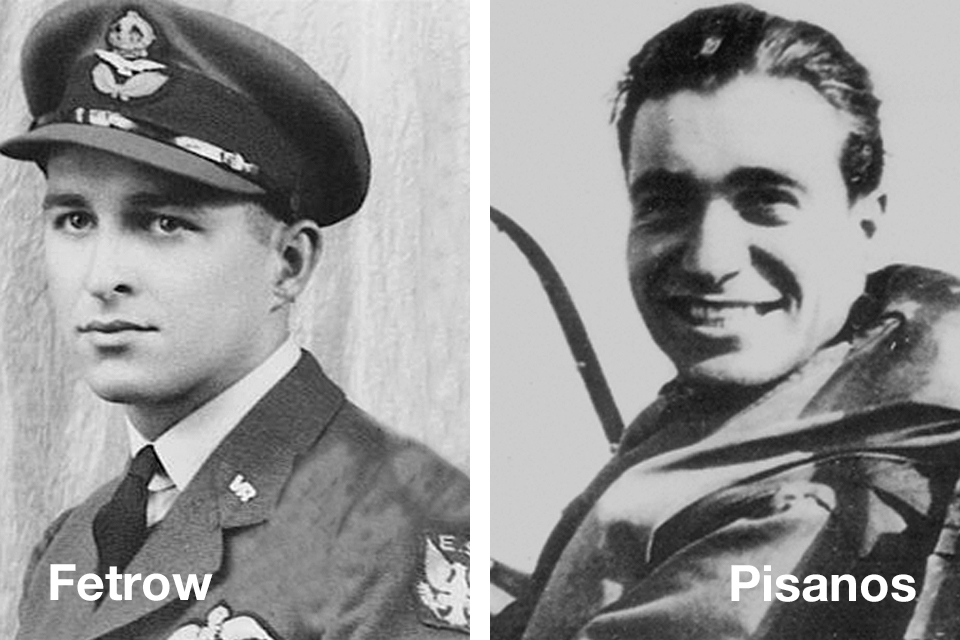

Among the Americans attracted by the prospect of flying Spitfires against the Germans were John “Red” Campbell, Art Roscoe, John Brown, Bill Geiger, Gene Fetrow and Spiro “Steve” Pisanos. Each signed up when the RAF recruiters toured the United States, and all eventually became members of the American Eagle Squadrons in the RAF’s Fighter Command. A total of 244 U.S. pilots eventually joined the three new Eagle Squadrons that had been formed. Roscoe and Geiger were assigned to No. 71 Squadron—the first to form up, on September 19, 1940—while Brown, Campbell and Fetrow were in No. 121 Squadron. Pisanos would later join 71 Squadron. The final Eagle Squadron was No. 133.

JOHN CAMPBELL, who had been flying since age 15, traveled from National City, near San Diego, to Hollywood to enlist in the RAF. The British turned him down because he was only 18, but three days later—having just turned 19 and carrying a letter from his parents—he came back.

“I arrived as a wet-behind-the-ears 19-year-old,” Campbell later recalled. “The British assumed we were there to do a job, and expected we would do it. This was quite different from the United States Army Air Forces, which assumed you couldn’t do it, unless you proved otherwise.”

Campbell already had significant flying experience when he joined up, and had also formed a picture of aerial warfare from the pulp magazines of the day. The popular magazines were instrumental as a recruiting tool, since many stories concentrated on the seemingly glamorous life of a fighter pilot. Campbell credited those magazines as the real reason he signed up. “I thought that every time you went up, you shot down five,” he said. He would learn that aerial combat was quite different in real life.

After flight training in the U.S. and Canada, he joined a convoy bound for England. At his assigned base, Campbell then checked out in a Miles Master. With the Battle of Britain already raging, he got three weeks of training in Spitfires, about 25-30 total hours, with no time on instruments.

“I only flew two ops in them, and they were enjoyable to fly,” he recalled. The Spitfire training started with “sitting for a half-hour in the cockpit with a flying sergeant putting me through cockpit drills.” The next morning he would check out a parachute, show the instructor he knew the cockpit drills and then taxi out, open up the throttle and take off.

Campbell then got to spend five weeks in Hawker Hurricanes—a total of about 54 hours—and, as he recalled, that was “more than most guys.” They flew two or three times daily, but the Eagle Squadron members were initially given old beat-up Hurricane Mark Is. Eventually the Americans received Hurricane IIb models, which they used on fighter sweeps through Belgium and northern France. Campbell felt the greatest difficulty in flying both the Spitfire and Hurricane was having to change hands from throttle to stick, and to the gear and flap controls.

Campbell really took to the Hurricane, and lamented the fact that the press largely overlooked it during the Battle of Britain. He noted that the “Hurricane got 80 percent of the kills, while the Spitfire got 100 percent of the credit. You never ran into a German pilot that was shot down by a Hurricane—they always said it was a Spitfire.”

He felt the Hurricane made a better gun platform, as it was more stable, and was best used against the German bombers. Spitfires were deployed at higher altitudes, and were more likely to engage enemy fighters. Campbell considered the Hurricane easier to land, stating,“It did not float like the Spitfire, you just flare to land, and it lands.”

In comparison to the German Messerschmitt Me-109E, Campbell said the Hurricane “lost most to the 109 at low level, where the 109 was faster, so we had to use tactics.” But he added that “at altitude, the Hurricane was faster, could turn better and had a better gunsight.”

Campbell also flew Hurricane IIcs at Gibraltar, which he described as “the first of the four-cannon-equipped models designed for tank busting.” He was later assigned to the Far East campaign, went to Port Sudan on an aircraft carrier, and took off from there for Java and Singapore. Stationed at Ceylon when the Japanese attacked, Campbell claimed “they got such a bloody nose that they didn’t try it again.”

Campbell believed that the “Hurricane could out-turn both the Mitsubishi A6M Zero and the Nakajima Ki.43 Oscar. In the slow, turning battles the Spitfire got eaten up, so Hurricanes remained in production until the end of the war.” He fought against both the Zero and the Oscar, and “got shot down twice, and I shot down two each of them.” The first time he went down, he made it back to his base after 21⁄2 days—to find all his personal effects gone. “I saw my wingman sleeping, and said, ‘Boo, this is the ghost of Red Campbell and where is my stuff?’ That woke him up in a hurry.”

After he was shot down the last time, over Java, Campbell became a prisoner of war for the duration of the conflict. Sent to a disease-plagued labor camp, he weighed only 98 pounds when the camp was finally liberated.

ART ROSCOE took his first flight at age 13, and from that point on always wanted to work in the aviation field. He got a job with Douglas Aircraft, and it was there that an RAF recruiter caught up with him in February 1941.

Roscoe recalled: “I had about 30-40 hours of flight time, and went out to Pomona to see how to get in [the RAF]. They told me to buy another 30 hours of flight time, and come back to see them then. I went back, took the flight test, and they let me know a couple of days later.” He went to flight school at Glendale, Calif., for another 75 hours, and then took a train to Nova Scotia to catch a steamer for England. His British flight training was in Spitfires at Landau with No. 53 Operational Training Unit.

“My Spitfire was never in really good shape, but you couldn’t get hurt in it if you stayed on top of it,” he remembered. “It could outturn practically anything; you could turn on a dime and have nine cents left.”

The No. 71 Squadron pilots were often tasked with escorting Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses on bombing missions, and frequently ran into Focke Wulf Fw-190As that had been lurking above them. The German fighters would typically make one pass, diving down on the bombers, while the Spitfires performed a split-S and went after them through the cloud cover. The Spits only had 15 seconds of .303-caliber ammo and six seconds of 20mm cannon rounds, so the pilots tried to make every round count. Roscoe recalled one particular B-17 escort mission to the Bay of Biscay, during which two Fw-190s attacked his flight: “The fellow in back of me got a cannon hit in his radio, so I was lucky.” He shot down his first enemy aircraft on October 2, 1941—an Me-109 over France.

In June 1942, Roscoe volunteered to help defend the island of Malta. He arrived at Malta on August 11 via the carrier HMS Furious, which was carrying a load of 35 Spitfires. The plan was to launch seven flights of five planes each, and just as Roscoe’s flight was taking off, the carrier Eagle was torpedoed and sunk while alongside Furious.

For the trip to Malta, they were given the Spitfire Vc, equipped with a tropical air filter. The planes carried only 90 gallons of fuel, mainly to assist in keeping their weight down for takeoff. Since the flaps had only full up and down positions, a wood block was inserted to hold the flaps at 15 degrees to assist in getting off the carrier. Once airborne, the pilots lowered their flaps, allowing the wood blocks to fall out, then raised them again.

“We were told ‘no crash landings,’ and if we got into trouble we were to head to Vichy French–held North Africa and hope for the best,” Roscoe recalled. All the members of his group made it to Malta. When they got there, the newcomers joined No. 229 Squadron, and found a lot of Battle of Britain veterans already fighting the Germans.

Roscoe said Malta was “a fighter pilot’s paradise—you went for the bombers first, had one crack at them, and then the fighters would be on your tail.” It didn’t last long, as most of the aerial fighting ended in October 1942, and they were restationed by the next month. Just before the fighting ended, Roscoe was severely wounded in a dogfight. Four cannon rounds from an Me-109 crashed through his cockpit, but only one hit him—in the shoulder. His plane was on fire, and the German pilot pulled up alongside for a look. Roscoe managed to kick his rudder, swerve behind the 109, and fire his cannons, shooting his tormentor down. He then crash-landed his Spitfire, as he was too weak to bail out.

Like many other Eagle Squadron members, Roscoe transferred into the USAAF when he was given the opportunity. “I had asked for [North American P-51] Mustangs, but ended up with the [Republic] P-47 [Thunderbolt]. It could out-dive practically anything—like a streamlined brick coming down,” he related. He ended the war as a squadron commander, with four confirmed victories, and another three probables.

JOHN I. BROWN III started out with Hurricanes, recalling that “of course everyone who signed up wanted to fly fighters, but we weren’t even guaranteed to fly. Some went to fighters, some to bombers and some to transports.” He quickly moved on to Spitfires.

“The Spit was very unforgiving; you had to fly with an iron hand and a silk glove,” Brown remembered. He also lamented having only 78 rounds of cannon ammunition, but said the 1,300-round-per-minute rate of fire for the .303 machine guns “could cause damage—chunks would fly off enemy planes—it could be very effective.”

Most of the missions were rather short, as his Spitfire had about two hours and 45 minutes’ flight time before it would be running on fumes. “We got about 90 miles into France, a very limited range, and coming back we had to land at the [British] coastal airfields,” he said.

“If you had your wings, it was assumed by the RAF that you could fly anything,” Brown stated.“I flew things I had never seen before. The attitude was that if you were going to get killed, do it in training. Don’t waste a plane on an operational mission.”

While at Duxford, Brown joined the USAAF and switched to the P-47. He recalled that the Thunderbolt “was one hell of an aircraft in combat, as it could take a lot of punishment.” In November 1944, he made another switch, this time to P-51s until the end of the war.

While flying the Mustang, Brown got some experience fighting against the new German jet fighter, the Messerschmitt Me-262 Schwalbe. He remembered that if a pilot called out “jet in the area,” everyone went down fast, like “a funnel to a beehive.” His group eventually claimed 22 of the Me-262s.

“Only the Mustang would try anything against them,” Brown recalled, noting the P-51 could do “600 mph in a dive, and could catch up with the 262.” Using that tactic, Brown and his flight leader went after a Me-262 that was on the deck, heading home. The German jets only had about 45 minutes of fuel. “My leader got it as it passed over the airfield, needing to land,” he recalled.

BILL GEIGER didn’t get to experience much combat during World War II. He did fly some bomber escort missions, recalling that in the summer of 1941, “we never lost a bomber to any fighters.” Shortly thereafter, he was shot down over the English Channel near Dunkirk while flying a Spitfire. German fighters had picked him off at about 15,000 feet over the Channel. He said:“My plane was on fire, and wouldn’t fly anymore. I banged on the cockpit [canopy]—it was supposed to slide but nothing happened. I beat on it with everything I had, then bent out a corner and let the slipstream grab it, and off it went. I popped out of the cockpit, and pulled the ripcord. I felt very much alone, but when I realized I was going to survive, the fear went away.”

A German boat picked up Geiger after he spent five hours in the water. Since it was still early in the war, the Eagle Squadron members were not supposed to wear their insignia, an order that Geiger had chosen not to obey. He recalled, “Not only was I wearing my insignia, I also had extras in my pocket.” Geiger realized he was in big trouble, and fully expected to be shot.

“I was led away by a German officer with a two-man squad, and I thought about running,” he remembered. The officer recognized Geiger’s Brooklyn accent, since the German had been a truck driver in New York before the war. It turned out that he had never become a U.S. citizen, and when Adolf Hitler urged all Germans to return to the fatherland, he went back. “He asked me if I was an American, and when I admitted it he told me that I was going to be all right,” Geiger recalled. It was the start of 31⁄2 years in a POW camp for Geiger—and the end of his war.

GENE FETROW was working at Douglas Aircraft’s Santa Monica plant when the war in Europe broke out, serving as an inspector for A-20 Havocs. Hearing from a friend that an RAF recruiter was at the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood, Fetrow went to see him.

“I told him I had been flying since I was 15 years old, mostly Fleet biplanes,” Fetrow recalled, “but he asked how many hours I had. I only had about 35, so he told me to get more time.” He signed up with a local flying school, and put in another 35 hours as quickly as possible.

Returning to the recruiter, Fetrow took a flight test in a Waco biplane and was told they would let him know if he was accepted. A few days later a confirming telegram arrived. They still wanted him to get more training before heading overseas, however, so Fetrow spent an additional 75 hours in Stearman, Ryan STS, Vultee BT-13 and North American AT-6 Texan trainers.

Arriving in England on a transport ship, Fetrow reported for fighter training. Flying Spitfire Mark Is and IIs, he accumulated about 70 more hours of valuable flight time.

Fetrow served in No. 121 Squadron, flying mostly the Spitfire Mark Vb equipped with two cannons and four .303 machine guns. He flew about 120 missions from England, and was part of the ill-fated August 19, 1942, Dieppe Raid, in which his aircraft was shot up pretty badly. The Dieppe Raid turned out to be the only operation of the war that involved all three of the American Eagle Squadrons. Fetrow supported the mission by providing low cover, one of a flight of four Mark Vbs that ran into trouble shortly after crossing the harbor at Dieppe.

As Fetrow told it: “I saw several Fw-190s to my right and down below strafing our people on the beach. I thought our top cover would take care of some of them, so I started taking my flight down. A 190 then came down on me and put a 20mm deflection shot through my wing and another into my radiator. I wasn’t hurt, but the engine was hurt—my oil cooler blew apart. The engine seized up over the Channel, I rolled upside down, but the canopy wouldn’t eject—it only rolled back about six inches. I had to beat it with my elbows to get out, and my cockpit was filling with smoke. Once I was out, it got real quiet, and I saw my Spit hit the water.”

Fetrow had managed to send out a Mayday call over his radio, and the Air-Sea Rescue team came out to retrieve him while he was still in his dinghy. But by the time he got back to base, the RAF had already listed him as missing in action. “All my stuff had already been divided—my camera, cigarettes and shoes—and it took about a week to get everything straightened out,” he recalled.“We really took a beating that day, but we got about as many of them as they did of us— about 100 shot down.”

Fetrow eventually was transferred to serve in the Italian campaign. In May 1944, he was flying with the RAF’s 1st Tactical Air Force, usually on one of two main missions. The fighters would escort Consolidated B-24 Liberators and Martin B-26 Marauders out of Sardinia on missions to destroy German lines of communication and transport, or they would conduct ground-strafing missions against anything that moved.

“I once saw an old donkey and peasant farmer pulling a cart of hay,” Fetrow related. “I put a couple of slugs into it, and it went sky-high. It had been full of ammo for the German troops.”

He recalled another time when they saw some Tiger tanks: “We couldn’t do much against them, as they were camped in a dry riverbed in the woods. I left two Spitfires up as top cover, and the rest dove down, with one pilot managing to hit their fuel dump. I dove down too fast and steep—very poor manner, a classic case of pilot error. I realized I was in trouble, and pulled back on the stick. I blacked out, the plane did a snap roll, and I came to while flying upside down through a dry wash. My wings were bent, rivets had popped, instruments were broken, but I nursed it back up to 3,000 feet.”

Fetrow managed to get the Spitfire back to Corsica, where he was amazed when the wheels came down. He made a fairly normal landing, but his aircraft was subsequently pushed into the scrap heap. Ground crews managed to salvage only the prop, engine, wheels, tires and radio. That experience was enough, however, to convince Fetrow of the aircraft’s structural integrity.

“The Spitfire was hard to land, but it had great brakes,” he remembered. “I got three Fw-190s while in Spitfires, so it was my favorite plane.”He also had some experience with the P-47 after transferring to the USAAF 335th Fighter Squadron later in the war, and served as a test pilot for many other aircraft.

Another problem with the Spitfire was in retracting the landing gear—“you had to change hands to do it,” Fetrow recalled. He also said the fuel tanks were poorly placed, especially the one in front of the instrument panel. “I lost a friend when that tank was hit, exploding into a fireball, which rapidly consumed the cockpit area.”

STEVE PISANOS was another guy who couldn’t wait to fight the Germans and signed up with an Eagle Squadron recruiter before the United States entered the war. Technically, he wasn’t officially an American. Pisanos had come to the States from Greece in the summer of 1938, and shortly afterward had taken basic flying lessons on his own. He had renounced his Greek citizenship, but it wasn’t until May 1943 that he became a naturalized citizen—while he was in London, of all places. Of that momentous event, he remarked: “Uncle Sam and I are best friends, and I felt nothing but gratitude. I was the first to become a citizen outside of the U.S.”

After advanced training, Pisanos shipped out to England in February 1942. He received instruction in tactics before joining an operational training unit, flying Miles Masters, Hurricanes, P-40E Kittyhawks and P-51A Mustangs during his final training phase. He was assigned to the 268th Army Co-operation Fighter Squadron, and began flying combat missions over Holland in the P-51A. Known to his fellow pilots as the “Flying Greek,” he came to the attention of Squadron Leader Chesley Peterson in No. 71 Squadron, and was officially transferred in early September 1942.

In his one month with No. 71, he flew Spitfires and Hurricanes before transferring into the 334th Squadron, 4th Fighter Group, VIII Fighter Command, at the end of September, when the Eagle Squadrons were disbanded. Pisanos noted that the American Eagle Squadron pilots were heavily recruited by the USAAF, as “in reality we had Ph.D. degrees in fighting—we had experience.” The recruiter said, “You come with us—you are an American, would you accept a second lieutenant [commission] in the Air Corps?” Once he was with the 334th, Pisanos flew the P-47 and briefly the P-51 again.

“The Spitfire was a great aircraft, but it was limited because it had no fuel capacity to go great distances,” Pisanos recalled. He also rated the P-47 in the same fashion, as it “could not stay with the bombers on long-distance missions, and the Luftwaffe would just wait there for the fighters to turn back.”

As for the P-51, Pisanos emphasized, “That was it!” He participated in the first escorted Berlin mission with the 4th Fighter Group on March 4, 1944, and when the Germans saw the P-51 escorting the bombers, he said they knew they had lost the war.

Pisanos wound up his combat career in spectacular fashion. On March 5, he shot down two German aircraft, giving him a total of 10 victories in the space of 110 missions spanning 300 combat hours. On the way home, his engine failed and he was forced to crash-land in France. Evading capture, Pisanos managed to join up with members of the French Resistance, and was based in Paris until it was liberated in August of the same year. Because he knew too much about the Resistance, Pisanos was permanently grounded for combat and sent back to the States, spending the rest of the war as a test pilot at Wright Field in Ohio.

The ranks of Eagle Squadron members have greatly dwindled over the past few years. In 2006 they held their last official reunion. Of the 17 living members at the time, only five were well enough to attend. John Brown, Gene Fetrow, Bill Geiger and Art Roscoe have already made their final flight. Steve Pisanos has finished his book of memoirs, which was released in December 2007.

Frank Lorey III is a federal- and state-registered historian with more than 340 articles and several books to his credit. He has appeared many times on the History Channel and does historical archeology work on military plane crash sites. For further reading, he recommends: The Eagle Squadrons, by Vern Haugland; and The Flying Greek: An Immigrant Fighter Ace’s WW II Odyssey With the RAF, USAAF, and French Resistance, by Colonel Steve N. Pisanos.

Originally published in the March 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.