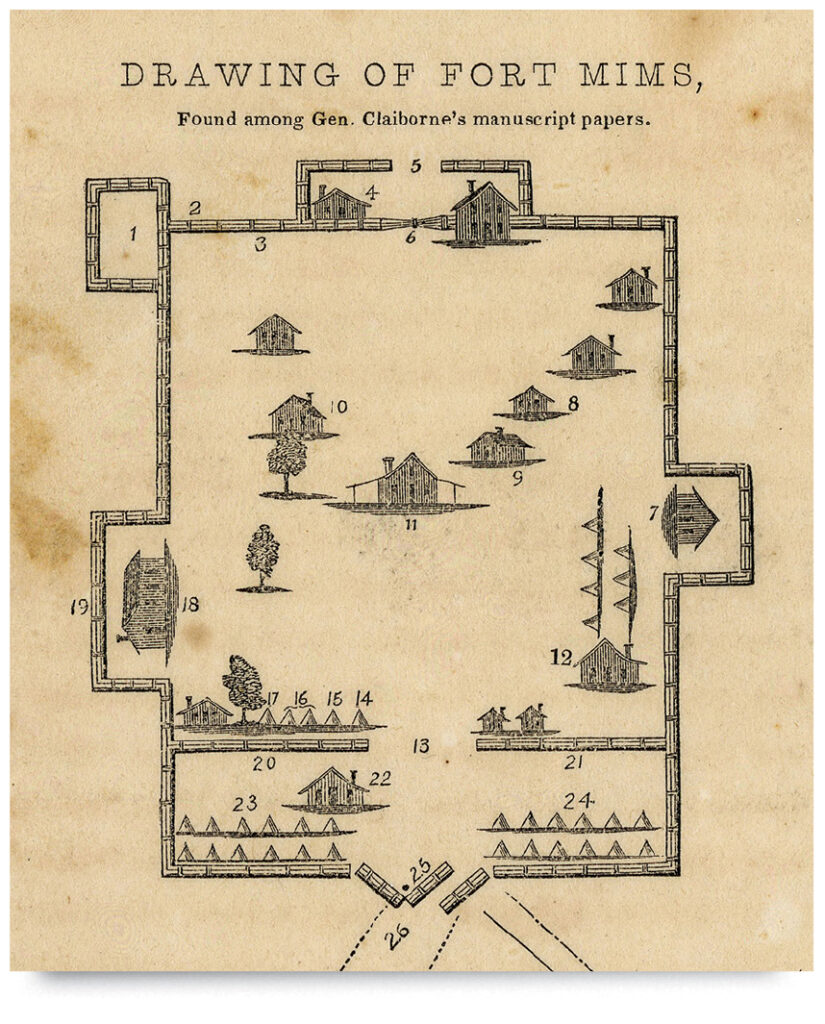

On August 30, 1813, a war party of 750 enraged American Indian warriors attacked a haphazard stockade known as Fort Mims in the southwestern corner of present-day Alabama, 50 miles from Mobile. After killing most of the 146 defending militiamen, the warriors turned on nearly twice that number of White, Black, and Métis (mixed indigenous and white) noncombatants, slaughtering scores of women and children with sickening ferocity.

The victorious assailants called themselves the Red Sticks, after the traditional red war clubs they carried. Until 1812, they also had belonged to the Creek (Muscogee) Confederacy, a loose alliance of largely autonomous villages, or talwas, that claimed a sprawling domain comprising modern Alabama and the western and southern portions of Georgia. Contact with British colonial traders in the late 17th century wrought the first significant change in the Creek domain. Those Creeks residing north and west of the trade route from the Carolinas became known as the Upper Creeks, those below it the Lower Creeks. The distinction was more than a matter of nomenclature. Living nearer to Whites, the Lower Creeks slowly shed much of traditional Creek culture in favor of accommodation. Upper Creeks tended to be traditionalists, profoundly distrustful of White encroachment, particularly once the American Revolution gave rise to an expansionist young Republic.

At nearly 25,000 members, the Creeks were the most numerous Indian people in the American South. The other indigenous tribes in the region were the Cherokees in northern Georgia and western North Carolina, and the Choctaws and Chickasaws, who occupied the northern two-thirds of present-day Mississippi. All three would side with the United States in the pending conflict. Spanish Florida would prove sympathetic to the Red Sticks but remained effectively neutral.

With the Fort Mims massacre, what had begun as a Creek civil war in 1812 metastasized into war with the United States. An outraged nation demanded vengeance against the Red Sticks. Total war was to be the price they paid, retaliation complete and unsparing. There was just one catch. The U.S. government, preoccupied with the War of 1812 against Great Britain, possessed neither the resources nor the will to confront the Red Sticks threat. Prospects consequently seemed good for the Red Sticks, who hoped not only to subdue the Lower Creeks, but also perhaps roll back the border with Georgia and expel White and Métis settlers from southwestern Alabama. Although the future of the Deep South hung in the balance, Tennessee, Georgia, and the Mississippi Territory would have to defeat the Red Sticks largely on their own. Georgia and the Mississippi Territory contributed invading columns to the conflict, but they made only brief and inconclusive gains. It fell to Tennessee to press home the fight.

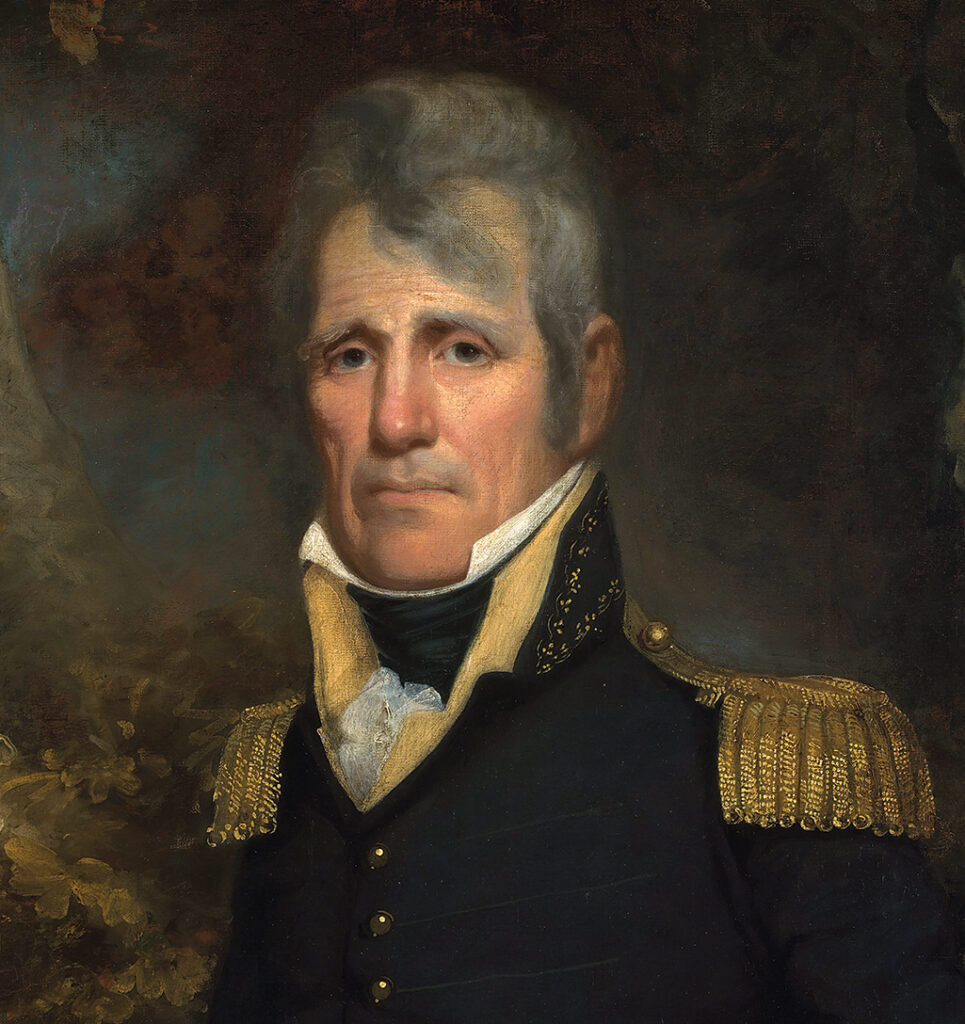

Enthusiasm for war ran high in the Volunteer State. “I hope to God,” said a Tennessee senator after Fort Mims, echoing the sentiments of his constituents “that as the rascals have begun, we shall now have it in our power to pay them for the old and new.” Tennesseans need look only to their own recent past, when Indian attacks were frequent and the state neglected by the federal government, to emphasize with the citizenry of the Tensaw. None reveled more in the prospect that victory offered to open vast new lands to Southern speculators and settlers than did the fiery, 46-year-old commander of the West Tennessee militia, Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson.

“Brave Tennesseans,” he proclaimed in a florid general order that exploited both frontier fears and avarice to spur recruitment, “your frontier is threatened with invasion by the savage foe. We must hasten to the frontier, or we will find it drenched in the blood of our citizens.” Jackson and Governor Willie Blount both were clear on the unique opportunity that the present crisis presented. Victory over the Red Sticks would be but the prelude to dispossessing all Creeks of their lands, dislodging the Spanish from West Florida, and preventing the pernicious hand of Great Britain from grasping the Gulf Coast.

Volunteers flocked to the banner. From his home in the quaint settlement of Kentuck, Tenn., the 27-year-old farmer and expert marksman David Crockett saddled his horse and journeyed 10 miles to join a new regiment of mounted riflemen. Crockett enlisted over the earnest objections of his young wife, Polly. They had only just settled on their latest homestead—the peripatetic Crockett frequently uprooted his family—and had two young boys and an infant girl to raise. David wrestled with his emotions. (The future American icon—the “king of the wild frontier”—never cared for the nickname “Davy.”) Although a proficient game hunter, he doubted his fitness for combat; he had killed plenty of bear, but never a man. “There had been no war among us for so long, that but few who were not too old to bear arms knew anything about the business,” he recalled. “I, for one, had often thought about war and had often heard it described, and I did verily believe that I couldn’t fight in that way at all.”

Then, too, there were Polly’s pleas to consider. “She said she was a stranger in the parts where we lived and that she and our little children would be left in a lonesome and unhappy situation if I went away.” Loyalty to a larger cause won out, however. “It was mighty hard to go against such arguments as these,” Crockett ruminated, “but my countrymen had been murdered, and I knew that the next thing would be that the Indians would be scalping the women and children all about there if we didn’t put a stop to it.” Besides, the term of service was merely three months, and the prospective pay hardly paltry. And so, on September 24, 1813, Crockett enlisted as private in the Second Regiment of Mounted Riflemen in General John Coffee’s cavalry brigade.

Crockett’s baptism by fire came little more than a month later. Jackson had penetrated the wild, mountainous northern fringe of the Red Sticks country hopeful of striking deep into the heart of the enemy domain. First, however, he must clear his left flank of 2,000 Red Sticks warriors purportedly gathered at Tallushatchee, a talwa resting eight miles from his newly constructed Coosa River supply-depot. Jackson assigned the task to Coffee’s mounted brigade.

Dawn on November 3, 1813, broke clear and chill over the clearing that cradled the clapboard cabins of Tallushatchee. As the darkness melted, General Coffee and 900 troopers glided undetected through the pine barrens. Two friendly Creek warriors guided them. Three miles short of Tallushatchee, Coffee divided his command into two parallel columns—the left element comprised of the cavalry, the right of the mounted riflemen clad in coarse linen trousers, long-tailed civilian shirts, and caped jackets called hunting shirts. Some men donned animal-skin caps, but not Crockett; he thought they made him look short. Suddenly, recalled Coffee, “the drums of the enemy began to beat, mingled with their savage yells, preparing for action.” Armed with bows and arrows, their sacred red war clubs, and a handful of muskets, the outgunned and outnumbered warriors (fewer than 200 actually were on hand) spilled from their cabins.

Coffee opened the fray. As the Red Sticks formed a hollow square, he hurled a company of mounted rangers at them. The rangers galloped to within musket range, fired some scattered shots, and then dared the Red Sticks to pursue. With a series of yells, the warriors complied “like so many red devils,” said Crockett, who watched from his position in the militia column. Catching sight of Crockett and his comrades, the massed Red Sticks veered toward them, unaware of the long line of cavalrymen in the timber on the opposite side of Tallushatchee. “We gave them a fire,” Crockett recalled, “and they returned it, and then ran back to their town.” Coffee ordered the encircling files to advance dismounted.

Pandemonium ensued. “Women and children darted from the cabins to surrender. Crockett saw seven women clutch at the hunting shirt of a stunned militiaman. He also counted 46 warriors running into a single cabin for a last-ditch defense. As Crockett’s company approached, a woman sitting in a doorway prepared to resist. “She placed her feet against the bow she had in her hand,” Crockett marveled, “and then took the arrow, and raising her feet, she drew with all her might and let it fly at us, and she killed a lieutenant.” The dead subaltern’s enraged men fired at least 20 musket balls into the woman. Her death elated the Tennesseans, who showed the Red Sticks in the cabin no mercy. “We now shot them like dogs,” Crockett confessed.

Bullets penetrated the thin clapboard walls handily, shredding those inside with splinters, balls, and buckshot. To complete the carnage, Crockett’s detachment set the cabin ablaze, burning the wounded inside to death. The gore made an indelible impression on Crockett. “I recollect seeing a boy who was shot down near the house.” Crockett would wrote in his 1834 Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of Tennessee. “His arm and thigh was broken, and he was so near the burning house that the grease was stewing out of him. In this situation he was still trying to crawl along, but not a murmur escaped him, though he was only about twelve years old.”

Scarcely a warrior escaped death, while Coffee counted just five of his men killed and 40 wounded, most slightly. Returning in triumph to Jackson’s supply depot, the victors, who had been on half-rations for days, discovered that the contractors engaged to feed the army had failed to deliver provisions. A ravenous Crockett and several of his companions returned to the battlefield in search of food. Combing the charred cabins and blood-soaked grounds, they found a potato cellar under the wreckage of the same cabin that had claimed the lives of the 46 doomed warriors. They hauled out a large cache of nauseating tubers. “Hunger compelled us to eat them,” remembered Crockett, “though I had a little rather not, if I could have helped it, for the oil of the Indians we had burned up on the day before had run down on them, and [the potatoes] looked like they had been stewed with fat meat.”

Five days later, Crockett again saw combat. An allied Creek chief had called upon Jackson to save his people, whom he said a large Red Sticks war party had besieged at the fortified post of a trader named Lashley near Talladega, a talwa just six miles distant. Jackson’s scouts returned with a heartening report. The Red Sticks had not encircled the friendly Creeks. Rather, they were congregated in a shrub-choked valley below the hilltop fort.

At sunrise on November 9, Jackson halted on the northern rim of the valley, his presence undetected by the Red Sticks. He quietly arranged his troops in battle order, telling Coffee to deploy his mounted men on the high ground to the east and west of the valley and join their flanks behind Lashley’s fort. To Crockett’s delight, the friendly Creeks streamed from the stockade, waving and crying, “How-dy-do, brother, how-dy-do.” After aligning his infantry on the northern rim of the valley, Jackson opened the action with an old Indian tactic. He sent three companies into the valley to roost the Red Sticks from their camp, and then wheel and dash back to the infantry lines. Painted scarlet and stripped to their breechclouts, the Red Sticks took the bait and chased the soldiers straight into Jackson’s ranks. Smoke rolled down the ridge, and the Red Sticks reeled in confusion. Repelled on one front, the Red Sticks rallied and then charged Coffee’s line.

“They came rushing forward like a cloud of Egyptian locusts and screaming like all the young devils had been turned loose, with the old devil of all at their head,” wrote Crockett. “The warriors came yelling on, meeting us, and continued until they were within shot of us, when we fired and killed a considerable number of them.” Crockett described the ensuing slaughter. “They broke like a gang of steers and ran across to our other line, where they were again fired on; and so we kept them running from one line to the other, constantly under a heavy fire.”

After an hour of futile battering at Jackson’s lines, several hundred Red Sticks survivors slipped through a gap between two units and fled. Nearly 400 Red Sticks died in the one-sided struggle. Jackson had inflicted a shattering but by no means war-ending defeat on the Red Sticks; they were too numerous and dispersed to collapse under the twin losses at Tallushatchee and Talladega.

David Crockett had no desire to stick around for the denouement. Together with most of Jackson’s volunteers, he quit the war at the expiration of his term of enlistment. In late January 1814, Crockett returned home to a joyous Polly, with $65.59 in pay and allowances in his pockets. Crockett would reenlist nine months later for a brief stint against the British in the Gulf Coast, but he saw no combat, his service ending before the Battle of New Orleans. “This closed out my career as a warrior, and I am glad of it,” he later wrote. Crockett had seen slaughter enough, and as his Narrative reveals, it clearly sickened him.

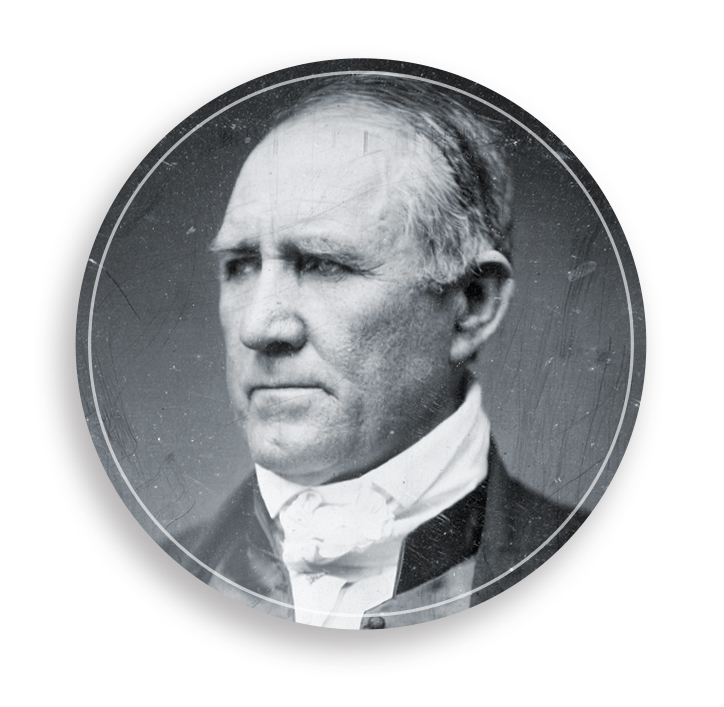

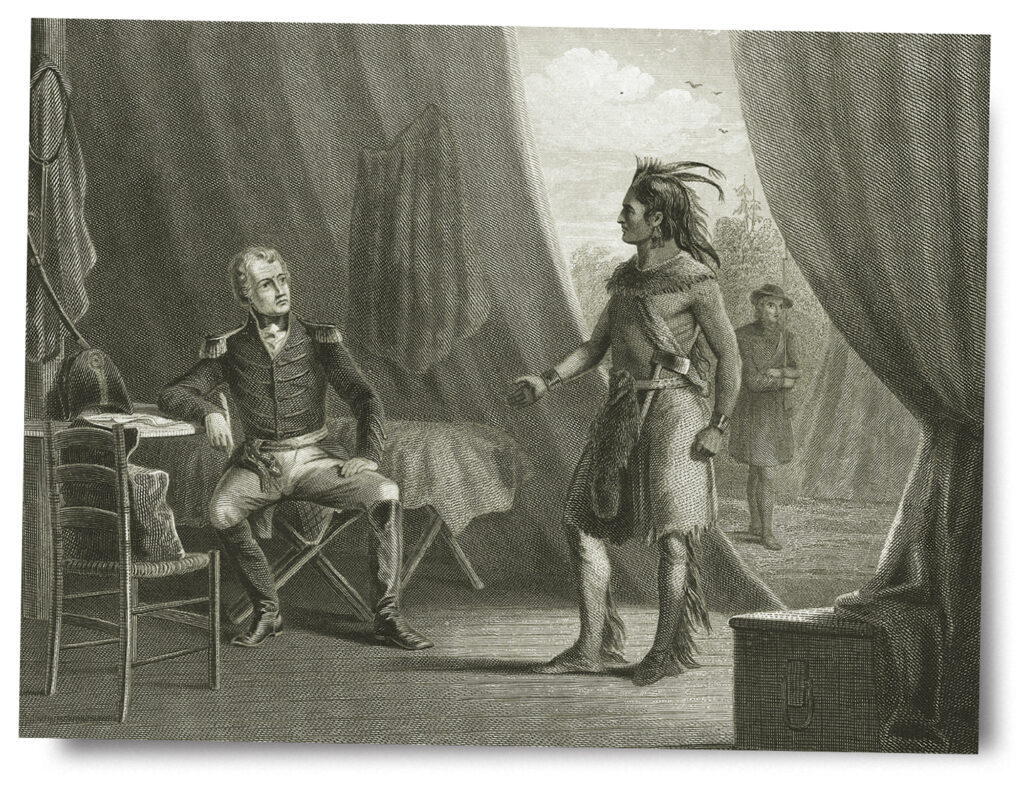

The 21-year-old fellow Tennessean Sam Houston began his Creek War odyssey a few weeks after David Crockett headed home from his first enlistment. A non-conformist by nature, at age 15 Houston abandoned the Kingston general store in which he clerked to live with the Cherokees, whose country abutted his family’s East Tennessee farm. The Cherokees took to the strapping white adolescent. The chief of the band adopted him, naming Houston “the Raven” after the bird the Cherokees believed symbolized good luck and wanderlust. Houston had not bucked the family traces entirely, however. He regularly visited his widowed mother and siblings, wheedling money from her with which to purchase a generous quantity of gifts for his adopted Cherokee kin.

In 1811, Houston returned to frontier society, fluent in Cherokee but intent on filling the gaps in his white education. He studied under a tutor and then opened a school for local children. Debt, however, soon drove him to resume clerking as well. Houston loathed the work no less than he had three years earlier. When in March 1813 the opportunity to enlist in the 39th U.S. Infantry regiment, then recruiting in East Tennessee, ostensibly for service against the British in the ongoing War of 1812, presented itself, Houston hastened to seize it. Being underage—the legal minimum age for service in the Regular Army was then 21—Houston first needed to obtain his mother’s permission, which she granted with an apparent admonition to never “turn his back to save his life.” That said, she slipped onto his finger a thin gold band with the word “Honor” etched in the inner curve.

A friend remembered when Houston “took the silver dollar.” Following the custom of the day, a recruiting detail from the 39th paraded up the dirt thoroughfare of Kingston with fife and drum. Silver dollars glinted on the drumhead as tokens of enlistment. Houston stepped forward, snatched a coin, and “was then forthwith marched to the barracks, uniformed, and appoint the same day as a sergeant.” Shortly after Houston left Kingston, admiring friends secured for him an ensign’s commission. Promotion to third lieutenant came apace. Lieutenant Houston cut a fine figure in uniform. Powerfully built, at six feet, two inches tall, he towered over most of the men of his platoon. His deep, commanding voice and eyes, as brilliant a shade of blue and as transfixing as those of Andrew Jackson, enhanced Houston’s natural gift for leadership. On the morning of March 27, 1814, staring intently at a gun-smoke-draped barricade, behind which thronged confidently jeering Red Sticks, the young lieutenant awaited his first test of combat.

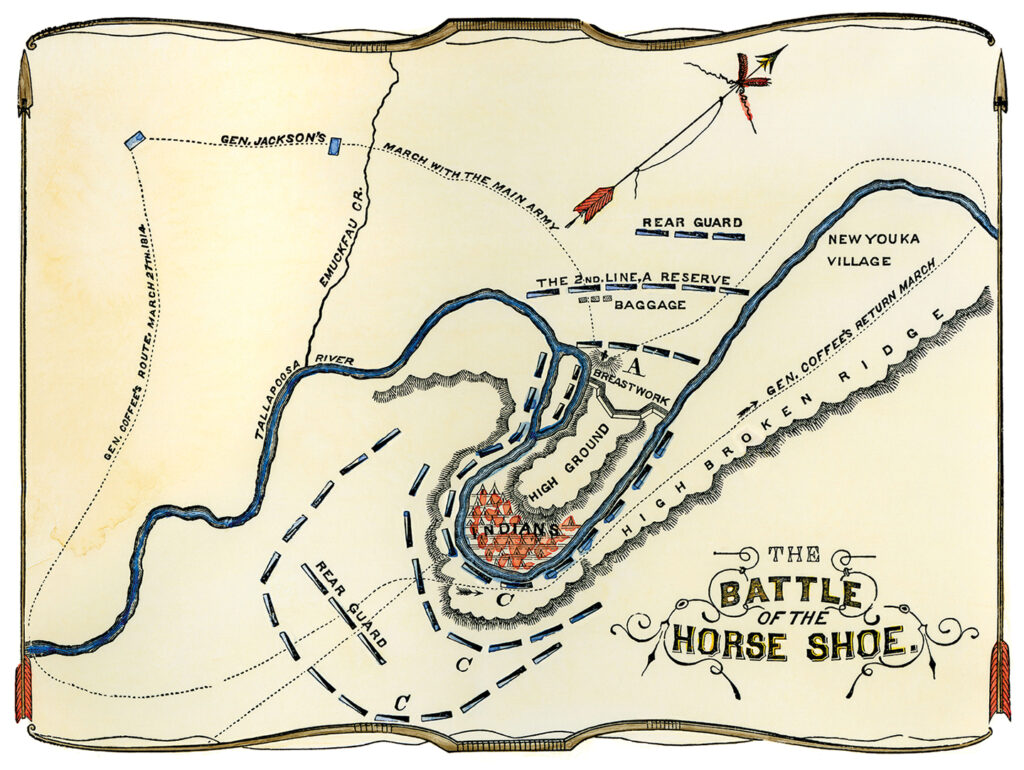

At last awakened to the danger a Red Sticks victory posed for the South, particularly if the British were to land on the Gulf Coasts, early in 1814 the War Department diverted the untried 39th U.S. Infantry to service under Andrew Jackson. With a command now numbering 3,200 men, Jackson advanced from his central Alabama supply depot on March 25, 1814, to challenge the strongest remaining Red Sticks contingent, nearly 1,000 warriors defending an enclave in a horseshoe-shaped bend of the Tallapoosa River, 70 miles northeast of present-day Montgomery. Along the south bank of the river rested the Red Sticks village of Tohopeka. Across the land approach to the village, the warriors had fashioned the most formidable obstacle American Indians would ever construct in their century of conflicts against the United States. A 350-yard-long wall of massive pine logs held in place with upright pine posts and props zigzagged across the neck of the 100-acre peninsula. In places the breastworks rise to a height of eight feet; nowhere were they less than five feet high. Clay chinking filled gaps between the logs. Two rows of firing ports were cut in the logs at regular intervals.

Jackson had devised a simple but ingenious plan—theoretically at least—to obliterate the Red Sticks and their refuge. At daybreak, General Coffee would ride down with his mounted brigade of Tennessee militia and 500 Cherokee warriors. They were to ford the river, come up on the Red Sticks from behind, and throw a cordon around the far bank of the horseshoe-shaped bend to prevent escape. Jackson, meanwhile, would march directly against Tohopeka with the infantry and an artillery company, batter openings in the breastworks with his two cannons, and then launch a grand bayonet charge against the weakened defenses. The 600 blue-coated soldiers of the 39th U. S. Infantry would lead the attack.

The battle did not unfold according to plan. The small cannon blasted away for two hours without even denting the barricade. Aligned in close order within musket range of the Red Sticks, the Regulars took casualties from enemy sharpshooters. Sam Houston and his comrades grew restless. Not until the Cherokee warriors spontaneously surged across the Tallapoosa and seized the Red Sticks village, causing warriors to stream from the barricade to rescue their families, was Jackson able to launch his assault.

The fight at the barricade was bitter but brief. Cheering Regulars rapidly punched gaps in the sagging Red Sticks ranks. On the extreme right of the regimental line, Lieutenant Houston climbed the wall with his platoon. He slashed at Red Sticks with his sword until a barbed arrow buried itself in his right groin. Hobbling about exhorting his men, Houston kept on his feet until the warriors opposing his platoon retreated to a log-roofed redoubt in a ravine beside the riverbank. Then he sank to the ground, bleeding and helpless.

Houston begged a fellow officer to extract the arrow. The man tried, but the arrow refused to budge. He tugged at it again with the same result. Furious and perhaps delirious with pain, Houston lifted his sword and threatened to cleave the officer’s skull if he failed a third time. The man yanked, and the arrow came out, together with a mass of tissue and a torrent of blood. Houston righted himself, struggled back to the barricade, and delivered himself to the regimental surgeon, who staunched the flow of blood.

After the collapse of the barricade, the Battle of Horseshoe Bend degenerated into a five-hour slaughter of Red Sticks that ended only with nightfall. Nearly 300 warriors died trying to flee across the Tallapoosa. Those who remained behind fought and died until only two clusters remained, one of which was the redoubt in the ravine near where Houston had been wounded. Jackson personally called for volunteers to storm the place. Houston, who lay near enough to hear the summons, labored to his feet, grabbed a musket, and summoned his men to follow him. Stumbling down the rocky ravine as twilight settled over the forest, Houston came within 15 feet of the redoubt before two musket balls struck him simultaneously, one in the right arm, the other in the shoulder. Drawing on his last reserve of strength, Houston turned to order his men to charge, only discover that he was alone. Houston staggered back up the ravine before collapsing. After dark, soldiers burnt the redoubt, immolating the occupants.

Night fell. The occasional musket shots, which signified Red Sticks survivors rooted out and dispatched, at least ceased. Surgeons, meanwhile, attend to army wounded, which numbered 159 in addition to 47 killed. Jackson’s Cherokee and Lower Creek allies suffered 23 dead and 47 wounded. The Red Sticks force had been all but annihilated, with nearly 900 dead and fewer than three dozen escaping unhurt. The Battle of Horseshoe Bend effectively ended the Creek War. It also catapulted Andrew Jackson to national fame and earned him a major general’s commission in the Regular Army.

On the battlefield that night, Sam Houston received only cursory care from the surgeons. A doctor bandaged his groin and extracted the bullet from his right arm. He was about to probe for the second musket ball when another surgeon suggested he desist. Houston, he said, had lost too much blood to survive the night, better not to torture him gratuitously. Laying Houston on the ground, the surgeons ministered to men whose odds of recovering they judged better.

Houston, however, refused to die. Shivering with cold, tormented by thirst, and racked with spirit-shattering pain, he passed the night of March 27, alone and ignored. When daybreak confounded the surgeons’ prediction, Houston was placed on a litter and carried swinging and jolting between two horses 60 excruciating miles to Jackson’s forward supply depot, where me might expire in relative comfort. Instead, he lingered on. Placed on another litter and fortified with whiskey between blackouts, Houston made it home alive. It would take him three years to recover fully.

David Crockett and Sam Houston had faced their respective baptisms by fire in the most consequential war between American Indians and the United States in the nation’s history. The Creek War opened the Deep South to the Cotton Kingdom, setting the stage for both the expulsion of all Indians from the South in the Trail of Tears in the 1830s and the Civil War three decades thereafter.

Destiny would eventually lead Crockett and Houston to Texas, where Crockett would meet his end on a merciless March 1836 morning at a crumbling former Spanish mission called the Alamo, and Houston would chart the course of Texas independence from Mexico. For both, the road to glory had begun in battle against the Red Sticks.

Peter Cozzens is the author of A Brutal Reckoning: Andrew Jackson, the Creek Indians, and the Epic War for the American South (Alfred A. Knopf, 2023)

This story appeared in the 2024 Winter issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.