Squire E. Howard awoke before dawn on October 19, 1864, to what he thought was thunder. The clamor, though, wasn’t coming from the clouds but from the fog enveloping the left flank of the Union Army of the Shenandoah at Cedar Creek—and the sounds accompanied a raging band of Confederate soldiers. “It was like the howls of the wolves around the wagon train in the early days of the great prairies,” he would write.

Captain Howard and his comrades in the 8th Vermont Infantry had anticipated another fight at some point, just not in the dead of night. Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early, however, wasn’t known to readily accommodate his opponents.

The Rebels’ initial fog-shrouded thrust that morning was chaotic, as the sleeping Union troops were quickly overwhelmed, many choosing to flee half-clothed rather than put up a fight. The retreat, recalled Captain D. Augustus Dickert of the 3rd South Carolina, was “a living sea of men and horses.”

When the attack began, the Union army’s colorful commander, Phil Sheridan, was resting 12 miles away in Winchester. His subordinates on site scrambled to respond, fortunate to receive additional time when famished Confederates stopped mid-attack to pilfer food and supplies from Union camps.

Among those trying to make sense of the situation was Brig. Gen. William H. Emory, the 19th Corps’ commander. Knowing he was ordering a likely suicide mission, Emory directed 8th Vermont commander Colonel Stephen Thomas to engage Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon’s attacking Confederates head-on. Gordon’s Division totaled roughly 2,000 troops. Thomas, in command of the 2nd Brigade that day, had about 800 men from four regiments, including the 8th Vermont.

Meeting again on the Cedar Creek battlefield 19 years later, Emory grasped Thomas’ hand and reflected: “I never gave an order in my life that cost me so much pain as it did to order you across the pike that morning. I never expected to see you again.”

A Budding Reputation

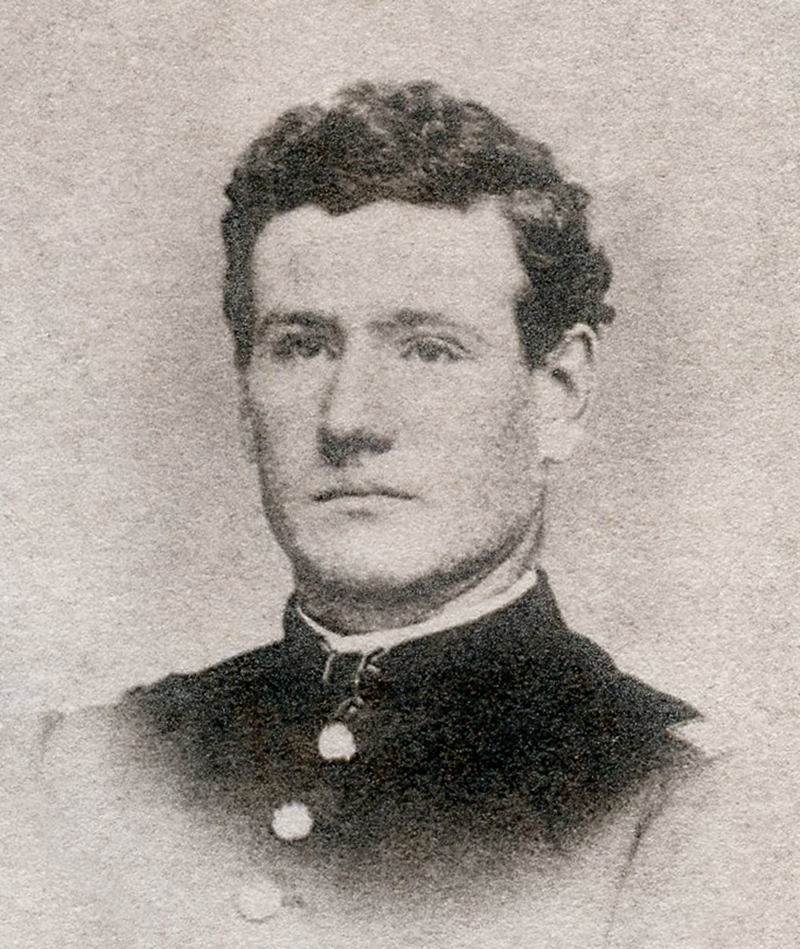

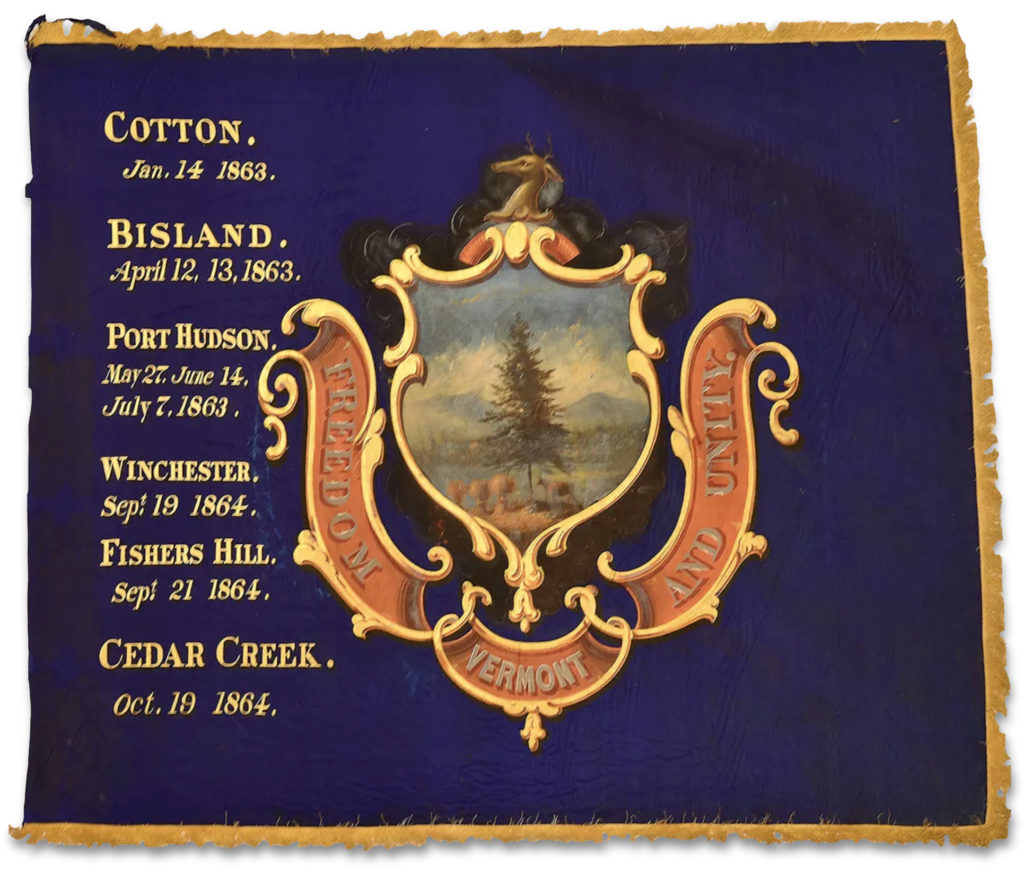

Formed in 1862, the 8th Vermont quickly developed a sterling reputation for bravery. Thomas, Howard, and Captain Moses McFarland were but a few of the regiment’s eventual list of standouts.

Thomas, gray hairs sprinkled throughout his dark beard, was a 51-year-old state representative with no military experience when the war broke out. A Democrat, he was hand-selected to lead the regiment. Though at first hesitant, “his patriotism overbore all his doubts,” wrote George Benedict in Vermont in the Civil War.

Howard had enlisted as a sergeant in Townshend, Vt., and received a Medal of Honor for heroism during the 1863 Bayou Teche Campaign. McFarland would be one of the 8th’s heroes at Cedar Creek. A 43-year-old father with piercing eyes, he was regarded for his stamina and drive. He also was no stranger to death, as only two of his five children survived past the age of 4.

In the summer of 1864, the regiment was called east from Louisiana to help repulse Early’s near-successful raid on the U.S. capital. It was then assigned to the 19th Corps’ 1st Division when Sheridan took control of the Army of the Shenandoah in August 1864.

At the Federals’ September 19 victory at Third Winchester (Opequon), the Green Mountain boys clashed with a soon-to-be familiar foe, Gordon’s Division—holding their line for two hours amid a relentless firefight.

Thomas then led a valiant bayonet charge, telling his men “we’ll drive them to hell.” Implemented without orders from above, the charge was another block in Thomas’ budding reputation as an inspirational leader.

“What Sheridan was to the army under him, Colonel Thomas was to his regiment,” Howard wrote. “Many had been the critical moments in our history when his level head and iron nerve had been our salvation.”

“More Like Demons”

At Cedar Creek, with Thomas now in charge of the 2nd Brigade, command of the 8th Vermont was handed to Major John Boardman Mead, a 33-year-old father of two. The undersized regiment did not hesitate in accepting the challenge of a showdown with Gordon, but as McFarland later wrote: “It was a sacrifice to the God of war of the few that the many might be spared, a propitiation offered against hope that out of defeat might come victory.”

The engagement with Gordon would last less than half an hour, many comparing the fighting to hell itself and the combatants to demons. After clawing their way uphill in the fog, the Vermonters entrenched in a wooded area. They were shocked, however, to see men in blue uniforms charging at them, whooping and hollering. Some of the Vermonters responded by opening fire.

“Captain, we are firing on our own men,” insisted Lieutenant Aaron K. Cooper, hunkered down next to McFarland. As McFarland replied, “I think not,” Cooper—his guard down—was riddled with bullets.

The men in blue coats were indeed Confederates, benefactors of the raids on Union tents earlier in the attack. “As the great drops of rain and hail precede the hurricane, so now the leaden hail filled the air, seemingly from all directions,” recalled Private Herbert E. Hill.

Steadily pushed back, the 8th managed to re-form in a ravine. McFarland, though, received news that Mead had been wounded, and Captain Edward Hall, his second-in-command, mortally wounded. The regiment was now in McFarland’s hands.

Hand-to-hand combat broke out. “Men seemed more like demons than human beings,” recalled Private Hill, “as they struck fiercely at each other with clubbed muskets and bayonets.”

The fiercest struggle was for the 8th’s colors. Corporal Alfred S. Worden had to fight off a bayonet attack by a stocky Confederate, who was shot dead by a fellow Vermonter. Corporal John Petrie, holding the colors, would be mortally wounded, crying out as he fell to the ground: “Boys, leave me…take care of yourselves and the flag!” But when fellow color guard Corporal Lyman F. Perham scooped up the colors, he was shot and killed almost instantly.

Engaged in what he called “the boiling caldron [sic] where the fight for the colors was seething,” Howard would be wounded twice, and later wrote that bayonets were “literally” dripping with blood amid the chaos, and that only one member of the color guard avoided being killed or wounded.

“It seemed as though we were passing into the very jaws of death and that the gates of hell were open to receive us,” McFarland wrote.

Overrun and taking heavy losses, the Federals eventually had no choice but to fall back. Howard, one of his shoes filling with blood from a wound, heaped praise on those who continued to engage in brutal bayonet clashes.

Although the regiment briefly re-formed to try to halt the Confederate surge, it was fruitless. “Longer resistance would have resulted in [the regiment’s] entire death and capture,” Mead wrote. It was indeed a horrific scene across the battlefield. Captain John W. DeForest of the 12th Connecticut recalled seeing pools of blood everywhere. “The firm limestone soil would not receive it,” he wrote, “and there was no pitying summer grass to hide it.”

Flipping the Script

As noted on the 8th’s memorial at the Cedar Creek and Belle Haven National Historical Park, the regiment had 110 killed or wounded out of 164 engaged, including 13 of 16 commissioned officers. But was the horrible sacrifice worth it? Those who survived said yes, having bought critical time for their army to re-form their ranks and launch its decisive counterattack.

Recounted Hill: “Bleeding, stunned, and being literally cut to pieces, but refusing to surrender colors or men, falling back only to prevent being completely encircled, the noble regiment had accomplished its mission.”

Incredibly, the 8th Vermont was not done fighting for the day. Howard was among those taken to a nearby field hospital, but Thomas took the lead in rallying the men. And, in what would long remain a contentious issue, the Confederate army decided to halt its attack. According to Gordon, that was Early’s call. The commander, he claimed, was satisfied enough with the morning’s progress: “Well, Gordon, this is glory enough for one day. This is the 19th. Precisely one month ago today [at Third Winchester] we were going in the opposite direction.”

By the end of the day, however, Confederate troops were again in retreat. Upon learning of Early’s surprise attack, Sheridan had mounted his charger, Rienzi, and ridden furiously to the battlefield from Winchester. Sheridan’s presence helped produce an inspired Federal counterattack that broke the Confederate line and re-established Union control of the battlefield.

The 8th Vermont, freshly removed from the “gates of hell,” had a big hand in the counterattack, flipping the script against a familiar foe: Gordon’s Division. Thomas led the way, and even when his horse was killed under him, he remained galvanized. Now under a bright sun, Early’s army was driven from the battlefield. The Vermonters followed the Confederates as far as Strasburg, about four miles. Most, unfortunately, would spend a difficult night without blankets, tents, or fires.

Cedar Creek marked the regiment’s last major action of the war. From that point on, it served mainly in a defensive role in the Valley.

Thomas received a Medal of Honor for his efforts in the battle, formally recognized for “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked.” (Three members of the 1st Vermont Cavalry also received Medals of Honor, as did Lt. Col. Amasa Tracy of the 2nd Vermont.)

Thomas became a Republican and reentered politics after the war, serving as Vermont’s lieutenant governor and in various other political and business positions before his death in 1903 at the age of 94. McFarland dedicated himself to repairing buildings and locations that had been damaged during the war before he died at 89 in 1911. Howard died in 1912 at the age of 72.

Cedar Creek was essentially the final major blow for the Confederacy in the Valley, but in reality Jubal Early wasn’t quite finished just yet.

For the Vermont soldiers, the battle was probably their most celebrated day. A large painting by Civil War veteran Julian Scott, hanging prominently in the state house in Montpelier, depicts the 1st Vermont Brigade’s counterattack. It features members of the 8th Vermont, including Thomas—visible in the background.

Mead recovered from his Cedar Creek wound, and in his official report to the adjutant general in September 1865 he acknowledged the regiment’s record of bravery and fearlessness: “I hope I may not be charged with egotism when I say, the 8th regiment was not excelled by any other in service in devotion to the cause for which it was raised, in its readiness and willingness to meet all necessary exposure and danger incident to a soldier’s life.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.