Fox Conner (1874–1951) was among the most influential American generals of World War II, despite having retired from active duty in 1938, three years before the United States entered the war. One of the Army’s most senior officers during World War I and the interwar years, Conner mentored several leading generals of World War II. His protégés included George Marshall, George Patton and Dwight Eisenhower. Throughout the war that trio regularly wrote the retired Conner, outlining their plans and seeking his advice.

During World War I Conner was the operations officer (G-3) of Gen. John J. Pershing‘s American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in France. Conner monitored closely as Marshall, the G-3 of the 1st Division, planned and coordinated the successful May 28, 1918, attack on the German position at Cantigny. It was the first division-sized American attack of the war. On the heels of that battle Conner had Marshall transferred to the AEF staff as his assistant G-3.

As American forces continued to arrive in France, the First Army was established in August 1918 as the primary U.S. fighting headquarters. Conner sent Marshall to the First Army as its G-3. Coordinating closely with Conner at AEF, Marshall went on to plan the great Allied victories at Saint-Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne. In the interwar years Conner continued to support Marshall’s career advancement. As the former approached retirement in 1938, he worked tirelessly behind the scenes to support Army Chief of Staff Gen. Malin Craig’s efforts to ensure Marshall would succeed him in office.

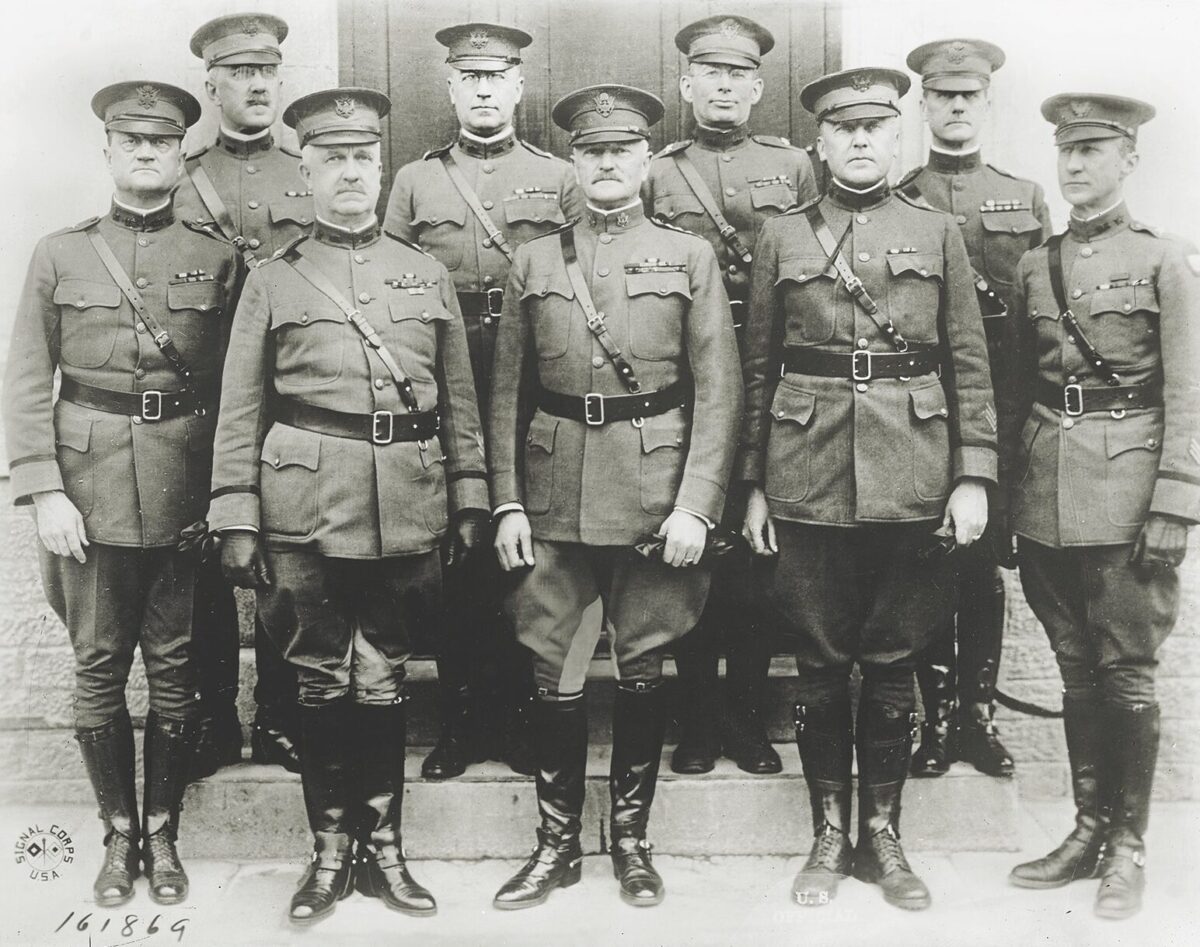

Conner met Patton in 1913 and they became lifelong friends, the senior-ranking Conner often playing the older brother role. In April 1917 both were on the AEF advance staff that traveled to England with Pershing (above, front and center). In the interwar years Conner intervened to prevent Patton’s abrasive nature from damaging his career. When Conner took command of the Hawaiian Department in 1927, Patton was the intelligence officer (G-2), though he had been reassigned from the position of divisional G-3 due to his personality. Conner worked to keep Patton under control.

Conner is best remembered, however, as “the man who made Eisenhower.” In 1920 Eisenhower’s friend Patton introduced him to Conner. A year later, when the newly promoted brigadier general needed an executive officer for his 20th Infantry Brigade in Panama, Conner tapped Eisenhower. According to Ike, his two years under Conner were the most profound period of his military education. Conner introduced Eisenhower to the principles of precise and methodical staff work. He also required his exec to read Carl von Clausewitz’s On War and introduced him to such authors as Plato, Tacitus and Friedrich Nietzsche. In 1925 Conner got Eisenhower a slot in the General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan. A year later his protégé finished first in his class. Eisenhower later referred to Conner as “the ablest man I ever knew.”

Conner impressed on Eisenhower three principal strategic war-fighting imperatives. Unfortunately, some of the United States’ military actions following World War II have fallen short of one or more of these imperatives.

Lessons:

- Never fight unless you have to. The 2003–11 Iraq War, aka Operation Iraqi Freedom, was clearly a war of choice rather than one of necessity.

- Never fight for long. Neither the Vietnam War nor the war in Afghanistan had clear strategic objectives, and both lasted far too long due to mission creep.

- Never fight alone. NATO was meant to ensure the United States would never again fight by itself, but its members didn’t support the U.S. intervention in Vietnam. During the post-invasion phase of the Iraq War the United Kingdom was the only significant NATO ally that stood with the United States. MH