Justices set high bar for public figures claiming press defamation

SCOTUS 101

LAYPERSONS TEND TO VIEW Supreme Court decisions in terms of winners and losers. However, the justices often find the most contentious aspects of a case to involve explaining the reasons for favoring the victor and devising a formula that will tell lower court judges how to handle similar cases. No case illustrates this better than New York Times v. Sullivan, the 1964 decision that, the Times editorialized on its 50th anniversary, “instantly changed libel law in the United States and still represents the clearest and most forceful defense of press freedom in American history.”

Sullivan arose over two principles in conflict: the right of the press to publish without government interference and the right of individuals to use the government—that is, the courts—to obtain recompense when defamed.

It was obvious from the moment that the justices agreed to review an Alabama Supreme Court decision ordering that the Times pay an astonishing libel judgment of $500,000 that the High Court was going to give the publication some relief. The question was how broad that relief was going to be.

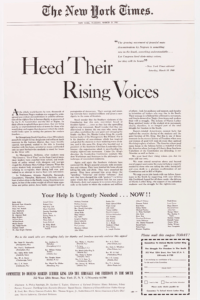

The politicians who brought the case claimed to have been libeled not in a news story or an opinion piece, but by a paid advertisement run in the paper on March 29. 1960. The full-page ad lauded the nonviolent civil rights demonstrations “Negro” students, in the ad’s language,

were staging around the South. The copy in the ad decried the “unprecedented wave of terror” meeting those demonstrators, and solicited donations to support the students, assist in aiding blacks to vote, and provide legal help to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The ad was signed by 20 Southern clergymen and 80 celebrities ranging from Eleanor Roosevelt to Jackie Robinson and including such show business luminaries as Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, and Shelley Winters.

One paragraph of the ad copy focused on actions against protesting students in Montgomery, Alabama. The ad named no individual official. However, L.B. Sullivan, the Montgomery city commissioner who oversaw the municipality’s police department, claimed that the mention unfairly cast aspersions on his job performance. Sullivan sued the Times and local ministers who had signed the ad. Alabama Governor John Patterson and other elected officials later joined Sullivan’s action.

The ad did contain misstatements, bolstering the plaintiffs’ case. For example, the ad said protesting students had gathered at the Alabama statehouse and sung “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” when in fact they had sung the National Anthem. The ad claimed that Dr. King had been arrested seven times on such minor charges as loitering; in fact, police had arrested him four times. The errors’ substance stopped mattering when the trial judge ruled that the standard “libelous per se” would apply—that is, that any factual errors, no matter how trivial, are presumed to harm a subject’s reputation. In setting damages jurors could assume plaintiffs had been injured, without requiring proof.

The justices had not heard a libel case in 20 years, but they knew this judgment could not stand. After the Alabama high court OK’ed the $500,000 judgment against the Times, so many Southern politicians sued the press for libel that state courts had $300 million in claims pending. “These kinds of cases provide a method to put newspapers out of business,” Hugo Black said as he and colleagues privately discussed the case.

Yet justices hesitated simply to say the trial judge was wrong to call the contested ad libelous per se. States make the rules for libel litigation, and in Alabama that harsh standard was the rule. The justices were not about to impose an overall national standard on run-of-the-mill libel suits.

Those who sat through oral arguments in the case expected the justices to dispose of the case by the easiest means. That would have been to limit their opinion to this particular dispute, holding that no jury reasonably could conclude that the ad’s authors had aimed their statements on police actions directly at the officials claiming to have been libeled.

But afterwards, conferring privately on the case, the justices saw the need for a broader ruling. Justice John Harlan cut to the core. “This case presents a classic illustration of how the First Amendment’s protection of the public interest in discussion must be accommodated against private rights—including the private right not to be defamed,” Harlan said. “We must lay down new constitutional rules for state libel laws.”

The justices felt that, rather than send the case back to lower courts to be tried under any new standard, the court had to apply those new rules to the Times case. All thought returning the case to Alabama would be disastrous. Jurors there were likely to be hostile to the Times and disinclined to parse any instructions’ legal niceties, especially since the original judge consistently had ruled against antisegregation efforts and in his courtroom made blacks and whites sit separately.

The solution for balancing the rights of the press—and the public’s need to be informed about government’s workings—against the rights of those claiming to have been libeled first was enunciated in the justices’ conference by Justice Tom Clark. “I would separate private libels from those on groups or in public affairs or government,” Clark said. “In private libels, I would allow a less onerous burden of proof.” That was not a radical idea. Courts in 16 states had narrowed public officials’ right to bring libel cases even when stories about them were false, as long as those publishing the stories had a reasonable belief that the articles’ contents were true and had acted without malice.

The justices had no trouble embracing a two-tier approach, but did struggle over criteria for lower courts to apply in assessing public officials’ claims of libel. Clark suggested that the writing under challenge had to relate directly to the official claiming injury, not merely to a policy that that official was pursuing. Chief Justice Earl Warren wanted the standard to be whether the contested article in its totality amounted to “fair comment” on a topic of public interest. Justice Harlan wanted a very high bar for any plaintiff; namely, to present “clear, convincing, and unequivocal” evidence—the standard in denaturalization cases involving efforts to revoke the citizenship of an immigrant who had been granted it. Justice William Brennan suggested plaintiffs should have to prove “actual malice.”

Brennan was assigned to write the opinion for the court. Seeking a middle ground among his brethren’s divergent views, he wrote six drafts before producing an opinion that most would accept—that to win a libel case, a public official had to prove either that the publisher had made the false statements knowing them to be untrue or had done so with a reckless disregard to gauging their accuracy. The ruling was a green light for the press to report aggressively on any public figure, since the Court in 1967 extended the Times standard to such persons.

However, while agreeing on the need to void the judgment against the Times Justices Black, William O. Douglas, and Arthur Goldberg wanted a more absolutist rule. They read the Constitution as barring any libel action by a public official—against the press or citizens—because even the threat of such action could inhibit the robust debate vital to democracy.