A congressional war panel proves too many cooks can poison the pot

By any standard, Ball’s Bluff was a fiasco. What began as a raid in October 1861 escalated into an unintended battle for Leesburg, Va. The Yankees so badly mismanaged the assault that the Union commander, Colonel Edward D. Baker, would almost certainly have been held responsible for the defeat—had he not been shot dead during the affray. What gave added import to the day’s events was the fact that the inept and tragically comical Colonel Baker was also a prominent Republican and a U.S. senator—the only senator ever to die in combat. The political response to his death would help to usher in an era of unparalleled congressional meddling.

“I want sudden, bold, forward, determined war,” Baker had thundered in the Senate, just before the Union’s equally disastrous stand at First Bull Run. He apparently had in mind the romantic Arthurian combat described in the epic poems of Tennyson and Scott. Baker—who attended congressional sessions dressed in full uniform, his sword displayed dramatically across his desk—was fond of quoting martial poetry, and did so even as his men came under fire at Ball’s Bluff. On the brink of a disaster he had initiated but was unable to comprehend, he greeted a bemused fellow colonel with a quote from “Lady of the Lake”: “One blast upon your bugle horn / is worth a thousand men.” He led his men into an impossible situation, and in the Rebel sniping and charge that followed, he discovered—all too briefly—the real meaning of “bold, forward, determined war.”

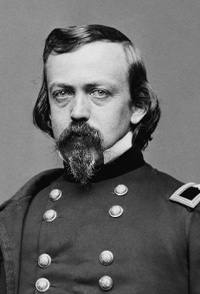

Congress, furious at the heroic death of one of its own, demanded a reckoning. In December 1861, both houses of Congress adopted a resolution to create a committee “to inquire into the conduct of the present war.” This Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War—or, the War Committee, as they came to be known—included four senators and four representatives and was guided by some of Congress’ most assertive Radical Republican members. In their analysis of the defeat, they ignored Baker’s culpability and found a scapegoat in his unsuspecting superior, Brig. Gen. Charles Pomeroy Stone.

Congress, furious at the heroic death of one of its own, demanded a reckoning. In December 1861, both houses of Congress adopted a resolution to create a committee “to inquire into the conduct of the present war.” This Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War—or, the War Committee, as they came to be known—included four senators and four representatives and was guided by some of Congress’ most assertive Radical Republican members. In their analysis of the defeat, they ignored Baker’s culpability and found a scapegoat in his unsuspecting superior, Brig. Gen. Charles Pomeroy Stone.

Stone, a West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran, had a sterling reputation, but had earlier earned the enmity of the committee’s more radical members by returning fugitive slaves to their owners, in accordance with his orders. To Radical Republicans on the committee, he was a “soft war” general.

As for the defeat at Ball’s Bluff, Stone’s superior, General George B. McClellan, knew exactly what had gone down: He had given the orders Stone followed. But McClellan not only blanched at interfering on Stone’s behalf, he ordered Stone to keep his own mouth shut regarding McClellan’s role. When questioned by the committee, McClellan swore his only knowledge of the Ball’s Bluff affair was what Stone had told him. McClellan then took his betrayal a step further. A Southern refugee from Leesburg had come along with a dubious bit of gossip about Rebel officers communicating with Stone. The story, an obvious concoction, should have been dismissed out of hand. But McClellan passed it along to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who ordered Stone relieved of his command and arrested. Stone was blameless, but the committee wasn’t having any of it. Someone must pay, and Stone—who didn’t share their anti-slavery zeal, and was therefore suspect—was fixed in their crosshairs.

The committee’s merciless and illegal treatment of Stone entailed unofficial allegations of treason as well as imprisonment for six months, much of it in solitary confinement, without formal charges or legal representation. He was not allowed to hear the evidence against him or to know the names of those who provided it. His treatment was in direct violation of the Articles of War, which guaranteed officers a prompt trial and a copy of the charges, but no one seemed to care. Not until February 1863 was Stone allowed to answer the preposterous charge that he had pre-arranged the Union defeat by colluding with the enemy. When brought into the light, the charges didn’t stand. Stone was restored to command, but his career had been destroyed, and he retired the following year. The War Committee had won its first victory against the military establishment.

The committee’s behavior toward Stone foreshadowed a three-year campaign of partisan-based persecution and pressure. Throughout the war, the committee did everything in its not-inconsiderable power to control every aspect of the Union’s military efforts—and they had the power to make their influence felt. Although the president was assigned the role of commander in chief, it was Congress that controlled the purse-strings. At times, the committee drove Lincoln to distraction and became, in the figurative words of one historian, “the deadliest sharpshooters in Washington.”

This was not the first time Congress had elected to use its investigatory power. There had been several committees established to probe military disasters, political intrigues and financial scandals since the late 1700s, and as recently as John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry. But this particular group of politicians, not content with merely observing and reporting, chose to direct the course of the war. The committee had the power to “inquire into the conduct of the present war,” to which end they could “send for persons and papers, and…sit during the sessions of either house of Congress.” And they used that power to institute a program of inquisitions against any officers whom they suspected of insufficient fervor in the pursuit of victory. The War Committee met frequently—272 times between 1861 and 1865—and, although the full complement of members was not always in attendance, the proceedings were well under the control of the majority party. And quite a group they were.

The two committee leaders, Senator Benjamin F. Wade and Senator Zachariah Chandler, of Ohio and Michigan respectively, were cut from the same cloth, as was House member George Julian. All were rabidly radical Republicans, unflinching in their belief that the war was being fought to put an end to slavery. They had little patience with anyone, including the president—who disagreed, or who advocated a policy of conciliation or gradual emancipation. The only senatorial Democrat among the members was Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, and he—and the other members—apparently had little trouble getting along with their more aggressive colleagues.

Ever critical of Lincoln’s approach to military matters, committee members’ solution to what they perceived as command deficiencies was to seek to place anti-slavery Republican generals in positions of high command. They paid no regard to the officers’ military experience or prowess. To their lights, this was still the age of the citizen army; it was the American farmer, the shopkeeper, the tradesman who had whipped the British, and the trappings of West Point and the experience of battle-scarred veterans of the Mexican War carried no weight. In fact, U.S. Military Academy graduates were looked on with suspicion and scorn. To Wade, who bristled at the number of West Point grads who had sided with the South, no such institution in the world had “turned out so many false, ungrateful men.” And to fellow committeeman Chandler, half were traitors and the other half Southern sympathizers. The War Committee—and to a great extent, Congress at large—tarred all West Pointers with the same brush, and trusted none of them.

The committee’s lack of insight is reflected in its list of favored generals: perennial loser Ambrose Burnside, limited and widely despised Benjamin Butler, hopelessly self-aggrandizing John C. Frémont, morally questionable Joseph Hooker and conniving and inept John Pope. The committee favored those general officers whose strong anti-slavery positions most jibed with their own, regardless of ability or performance. It was enough that Butler, for instance, had advocated the use of black troops, and Frémont had declared his own early version of an emancipation proclamation. Their zeal made them acceptable; victory surely would follow. What the committee did not understand, and what Lincoln would eventually come to recognize, was the war could not be won without seasoned and, more important, effective military commanders.

George McClellan and George Gordon Meade, through their less than stellar performance on the field, reinforced the committee’s prejudices. Meade was a Democrat—as was McClellan—and suspected by some of being a Copperhead. He had permitted Lee’s battered Army of Northern Virginia to escape across the Potomac after Gettysburg, arguably extending the war nearly two more years and reportedly reducing President Lincoln to tears of grief and frustration. And McClellan, despite being a splendid organizer, displayed an infuriating unwillingness to risk his superbly trained army in actual battle.

McClellan would eventually have his turn before this Star Chamber. Although warned by friends and supporters—and by Lincoln himself—of Congress’ growing impatience with his lack of progress, McClellan chose to read the warnings as personal affronts. He had been training the Army of the Potomac for five long months and was showing no sign of placing them in harm’s way any time soon. Inevitably, whispers of treason began to emanate from the committee, and McClellan was summoned. After hearing “Little Mac’s” lengthy and less-than-aggressive plan, Chandler sarcastically concluded, “General McClellan, if I understand you correctly, before you strike at the rebels you want to be sure of plenty of room so you can run in case they strike back.”

“Or,” added an equally caustic Wade, “in case you get scared.”

McClellan delivered a rambling response, closing with, “[W]e must bear in mind the necessity of having everything ready in case of a defeat, and keep our lines of retreat open.”

Given his audience, McClellan’s response bespeaks either boundless hubris or abject stupidity. After the general left, Chandler said to Wade, “I don’t know much about war, but it seems to me this is infernal, unmitigated cowardice.”

When Chairman Wade presented the president with a report of the exchange, he demanded Lincoln replace McClellan “with anybody!” Lincoln, bereft of acceptable command choices, answered, “Wade, anybody will do for you, but I must have somebody.”

In early March 1862, the War Committee came to Lincoln with a plan for restructuring the Army of the Potomac into corps (which would result in a reduction of McClellan’s authority) and promotions for various generals the committee favored. Despite McClellan’s objections, Lincoln complied, issuing General War Order No. 2, elevating to corps command Republican Generals Irvin McDowell, Edwin V. Sumner, Samuel P. Heintzelman, Erasmus D. Keyes and Nathaniel P. Banks, and designating Republican Brig. Gen. James Wadsworth as military governor of the District of Columbia. McClellan was on the way out.

Disappointing as Meade and McClellan were, they were not traitors. Lincoln knew his officers’ problems were rooted in mediocrity and inexperience, not disloyalty. But while he was less concerned with placing blame than in obtaining results, the War Committee freely pursued its “treason” witch-hunt for the duration of the war.

Committee members deployed all the conventions of partisan politics. They foisted inexperienced or undeserving candidates on Lincoln, leaked sensitive information to the press, used unaccredited testimony and tainted or fabricated evidence to neutralize generals of whom they disapproved and ultimately drove a wedge between the corps of general officers and Congress that remained fixed throughout the conflict. All hope of trust and viable communication between the military and the government was irrevocably damaged.

When he was campaigning, Lincoln could be as partisan as any other politician; he played the game with skill. But now he had a war to win, and he needed the support of Northerners of all stripes; without compromise, the task was impossible. Even with compromise, unity was often beyond reach, as evidenced by the resistance to conscription shown in the 1863 Draft Riots in New York. Lincoln’s four years in office were a constant exercise in diplomacy, with the preservation of the Union his foremost goal. It mattered little to War Committee members. As far as they were concerned, Border Staters and Union Democrats were all suspect.

Overbearing they might have been, but Wade, Chandler, Julian and their fellow committeemen weren’t monsters. They were, in fact, moral-minded men who believed in immediate and universal freedom, and who realized before most Americans that the war was, in fact, being waged over slavery. Their proposed policies, however, were divisive, and their methods undermined the nation’s faith in its military and to some extent, in its president. Lincoln, for his part, prevailed on some occasions; on others, he gave in to political expediency and let the committee have its way.

None of this means the War Committee made no positive contributions to the war effort. In fact, it proved effective in a number of areas: investigating alleged Rebel war crimes, including the massacre of captured black soldiers at Fort Pillow; overseeing the humane treatment of prisoners of war; looking into the proper care of wounded soldiers; curbing illegal commerce with states in rebellion; attempting (not altogether successfully) to monitor the proper fulfillment of government contracts; advocating the use of black troops; and unceasingly promoting emancipation.

And—for better or worse—the committee was diligent in its investigations of such Union disasters as the Crater during the Siege of Petersburg in July 1864. It turned out four voluminous annual reports citing the results of seemingly endless hearings, ranging from the losses at Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff to the shameful massacre of friendly Cheyenne at Sand Creek in November 1864. But efforts to appoint generals on strictly political grounds, to derail generals whose politics members didn’t like and to constantly curb and control the efforts of the chief executive proved obstructive. In seeking to ferret out treason where none existed, in the de facto presumption of guilt and in the use of egregious, extra-legal methods, the committee set the tone for the McCarthy hearings of the 1950s.

While the over-zealous members of the War Committee remained fixed in their views, their methods and their purpose, Lincoln grew in office. Through a long, frustrating and costly process of elimination, he matured as a commander in chief. He selected the right men for the task at hand, and learned how to wage war effectively. Lincoln would never be completely free of the committee’s sway; it would prove a source of frustration to the very end. Ultimately much of what Lincoln accomplished was in spite of, rather than because of, its influence.

Ron Soodalter is a columnist for America’s Civil War.