In 1999 Kiowa beadworker Teri Greeves stood in line to enter an umbrella for judging at the Santa Fe Indian Market, the world’s oldest and largest juried Indian art show, held each August in the New Mexico capital. It wasn’t a typical umbrella, of course, but an antique frame spanned by a 3-by-3½-foot brain-tanned deer hide adorned with beads, abalone shell, turquoise, metal studs, Indian head nickels and cloth. The entry stumped the judges. “They didn’t know what it was,” recalls Greeves, 45. “They wanted me to define it as to what it was in their classification, their category. They wanted me to argue it.”

What the judges also didn’t know was that Greeves had just completed studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and was preparing for the LSAT with plans to enter the University of New Mexico law school and pursue a legal career specializing in American Indian issues. “I told them, ‘I don’t know whether it’s traditional or contemporary,’” Greeves recalls. “‘My mom, you can say, wears them traditionally when she goes to powwows. But this is contemporary, because I’ve never seen one before. So you tell me.’”

Indian Parade Umbrella ultimately won best of show at the market and sold for $10,000. “I was so green to the Indian market that I didn’t know what best of show was,” she admits. “I thought I’d won best of beadwork—and back then they didn’t even have a beadwork category.” Greeves in turn decided she could “fight the good fight” without becoming a lawyer by tackling Indian and women’s issues in her beadwork. She hasn’t slowed down.

“I usually say I’m a beadworker,” Greeves says from her studio outside of Santa Fe. “And when they give me that weird look, like, ‘What the hell is that?’ I say, ‘I’m an artist,’ because the medium I work in itself is so defined by craft that it’s not really recognized broadly as a valid artistic medium.”

Greeves has done much to change that perception, exhibiting her works at the Denver Art Museum, the Heard Museum in Phoenix, the Museum of Art and Design in New York, the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and the British Museum in London.

Her Kiowa mother, Jeri Ah-be-hill, married Italian-American sculptor Richard Greeves and moved to Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation, where Jeri ran the Fort Washakie Trading Post. It was there Teri first saw—and eventually sold—beadwork from various tribes. “I grew up surrounded by all those amazing beaded objects,” Teri recalls.

At about age 8 Teri learned to make her own beadwork. While her mother was not a beadworker, her Kiowa grandmother had been, earning recognition at New Mexico ceremonials and county and state fairs. So was her Shoshone aunt, Zedora Enos, and that’s who taught Teri the craft. Greeves’ first work was a pair of baby moccasins.

“What Zee really told me was to look at the overall object,” Teri recalls. “When we were done with the moccasins, it was the negative space created with those beaded lines that created the pattern—a deer hoofprint. That space informed the viewer as to what the moccasins meant. And so from the moment I first started working on beadwork, I didn’t just see it as a way to cover things up.”

Meanwhile, her mother taught Teri about business. Jeri sold her daughter the necessary supplies at wholesale and had Teri put together a display board for the curios she sold.

Though Teri grew up on the reservation, she often felt like an outsider. “I was an outsider because I was half-white and wasn’t Shoshone, either,” she says. “I know other creative people who have similar experiences. It’s one of those observational points. You’re always looking from the outside in.”

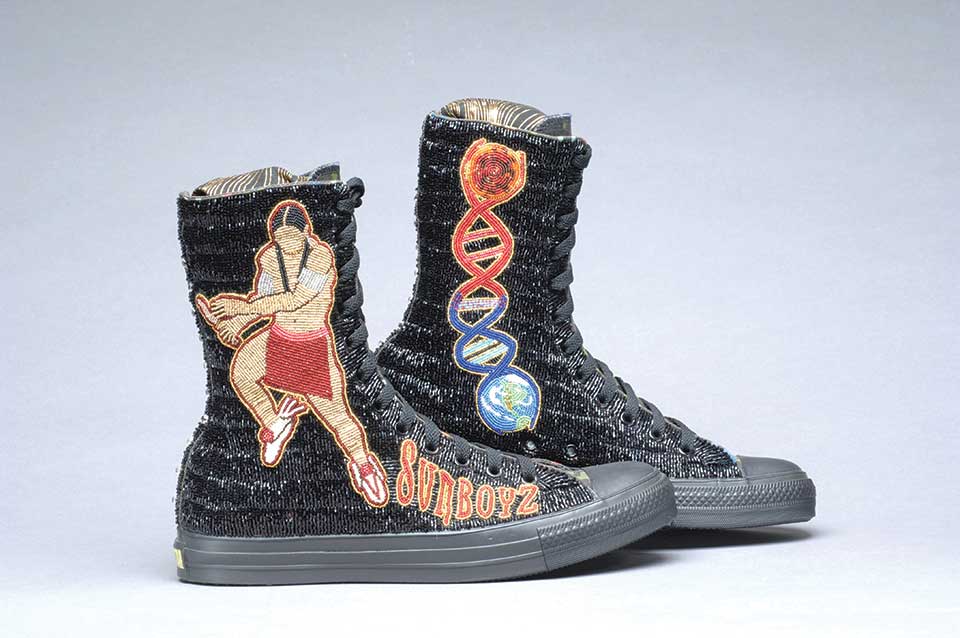

Greeves parents later divorced, and Teri and her mother moved to Santa Fe in 1986. The young woman studied at St. John’s College in Santa Fe and Cabrillo Community College in Aptos, Calif., before moving on to Santa Cruz, all the while making and selling beaded tennis shoes and other nontraditional works for book or rent money. “I didn’t want to just make beaded mocassins and pipe bags,” she explains. “I never felt bound by those traditional objects.”

Greeves has no regrets about abandoning her dream of practicing law. She likes fighting the fight in her own way. “Part of it is fighting for sovereignty, mutual respect,” she says. “That’s what my great-grandfather fought for as a Kiowa person. That goal is what I try to bring through in my work. If I can make an object that is so beautiful, that someone comes over to see and then walks away realizing what it is to connect to a Kiowa person—I mean similar things flow through all of us—if I can do that, then I’m still fighting the good fight.”

Greeves would have made a pretty good lawyer.

“My husband tells me that all the time,” she says with a laugh. WW

See more of Greeves’ work on her website. Johnny D. Boggs, a special contributor to Wild West, writes award-winning fiction and nonfiction from Santa Fe, also home to many art galleries. Originally published in the December 2015 issue of Wild West.