“What shall we do with the Negro?” was a question posed in Northern newspapers as early as the summer of 1861. The question, of course, revealed an underlying attitude— white people still regarded African Americans as objects, not equals, and not a part of the polity. The status of freed slaves clearly presented a problem for the North. But in fact it played an important role in Confederate war councils as well. And ultimately the conflict proved how unready either side was to deal with it constructively.

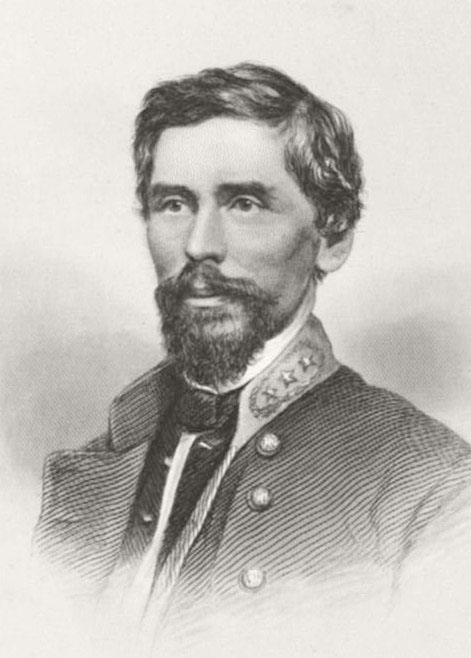

The first serious proposal to overturn the Confederacy’s system of racial slavery came from a surprising source: Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne, a zealous supporter of Southern independence, who was supported in his views by 13 other high-ranking officers in the Army of Tennessee. An Irish immigrant who had established himself as a successful lawyer in Arkansas, Cleburne became one of the Confederate Army’s finest commanders. By January 1864, however, he viewed the Confederacy’s dimming prospects with dismay.

Others Southerners had earlier voiced concern about the future of former slaves. After the fall of Vicksburg in July, a few citizens of Mississippi and Alabama had also felt the despair that weighed on Cleburne. In September 1863, the Jackson Mississippian had opined, “We must either employ the negroes ourselves, or the enemy will employ them against us.” The Mobile Register decried the “danger to the South” from Northern use of black soldiers. Its editor asked, “Why not, if necessity requires, meet them with the same fighting material?” The Montgomery Weekly Mail urged its readers to bow to that same necessity, even if it was “revolting to every sentiment of pride, and to every principle that governed our institutions before the war.”

But no one developed as thorough an argument for arming and freeing the slaves as Cleburne. The “present state of affairs” was grim, the general pointed out in a proposal that he sent to his immediate superior. Confederates had sacrificed “much of our best blood” and immense amounts of property, yet they were left with “nothing but long lists of dead and mangled.” The South’s forces, “Hemmed in” and menaced “at every point with superior forces,” could “see no end to this except in our own exhaustion.” A “catastrophe” lay “not far ahead unless some extraordinary change is soon made.” Cleburne felt the South must act to avoid “subjugation” and “the loss of all we now hold most sacred.”

“Three great causes,” he wrote, were “operating to destroy us.” Most fundamental was the Army’s inferiority in numbers. Closely related to that problem was the Confederacy’s “single source” of manpower compared to the enemy’s “several sources.” Cleburne’s third cause was the most controversial: “slavery, from being one of our chief sources of strength at the commencement of the war, has now become, in a military point of view, one of our chief sources of weakness.”

Jefferson Davis had recently proposed several steps to increase the size of the Army, but Cleburne said these were simply inadequate, listing the reasons why. Many deserters were outside Confederate lines and would not make reliable soldiers, even if captured. Ending substitution would merely bring into the Army an “unwilling and discontented” element. Drafting young boys and old men would “swell the sick lists more than” augment the ranks. The South’s economy needed most of the men who were currently exempt, so few additional men could be gained from that source. Only Davis’ idea of using black men “as wagoners, nurses, cooks, and other employe[e]s” made sense to Cleburne.

But he and his fellow officers also urged a far more drastic step: “We propose that we immediately commence training a large reserve of the most courageous of our slaves, and further that we guarantee freedom within a reasonable time to every slave in the South who shall remain true to the Confederacy in this war.” To make that shocking proposal more palatable, Cleburne claimed that “every patriot” would surely prefer to lose slavery rather than his own independence—choose to “give up the negro slave rather than be a slave himself.”

More eyebrow-raising assertions followed. Slavery, the general declared, “has become a military weakness,” and in point of fact the Confederacy’s “most vulnerable point.” Not only were black soldiers swelling the Union ranks, but slavery was also undermining the South from within. “Wherever slavery is once seriously disturbed” by Union advances, whites ceased to “openly sympathize with our cause,” he claimed. “The fear of their slaves is continually haunting them,” and “they become dead to us.” Meanwhile, the slaves worked as “an omnipresent spy system,” aiding Union troops. Cleburne added, “for many years the negro has been dreaming of freedom,” and it would be “preposterous” to “expect him to fight against it.” It was equally preposterous to expect him to fight for the Confederacy without it. “Therefore when we make soldiers of them we must make free men of them beyond all question, and thus enlist their sympathies also.” The South, Cleburne emphasized, had to face “the necessity for more fighting men.” After countering possible objections and arguing that slaves could make good soldiers, he closed by urging prompt action on what he described as a “concession to common sense.”

Throughout most of 1864, Cleburne’s proposal went nowhere. His superior, General Joseph E. Johnston, declined to forward it to Richmond on the grounds that “it was more political than military in tenor.” But another Army of Tennessee officer, scandalized by the notion of interfering with slavery, sent the document to Jefferson Davis in protest. At that point the Confederate president directed that Cleburne’s idea should not even be discussed. With an eye on the 1864 elections in the North, Davis wanted to avoid dissension in the Southern ranks. He was hoping that the image of a strong, resolute Confederacy might help to defeat President Abraham Lincoln. But after the fall of Atlanta in September 1864, Davis knew his strategy had failed. The Army had to be enlarged.

On November 7, 1864, Davis urged Congress to increase the number of slaves used by the Army to 40,000. To reach that number he recommended purchasing the slaves and “engaging to liberate the negro on his discharge after service faithfully rendered.” This amounted to proposing a sizable program of compensated emancipation. More significant was his statement that “should the alternative ever be presented of subjugation or the employment of the slave as a soldier, there seems no reason to doubt what should then be our decision.”

This message was the cautious opening move in the Davis administration’s plan to arm and free the slaves. Within a few weeks Davis and his allies were pressing forward with their maneuver, both inside the Confederacy as well as abroad. In hopes that emancipation might help the South to gain European support, Davis sent Duncan Kenner to England and France. A wealthy Louisiana slaveholder who had independently advocated enlisting and freeing slave soldiers, Kenner readily accepted his diplomatic instructions.

On the home front, the administration used Robert E. Lee, whose prestige within the Confederacy surpassed the president’s, as its primary advocate. At the suggestion of Secretary of State Judah Benjamin, Lee invited his men to speak out, and most declared that they needed and wanted black reinforcements. More important, Lee himself called for bold steps. In January he wrote a Virginia legislator that the Confederacy should raise African-American troops “without delay.” Lee not only had confidence that they could “be made efficient soldiers,” he also argued that the Confederacy should capture their “personal interest” by “giving immediate freedom to all who enlist, and freedom at the end of the war to the families of those who discharge their duties faithfully (whether they survive or not), together with the privilege of residing at the South. To this might be added a bounty for faithful service.” A similar letter, this one to Mississippi Congressman Ethelbert Barksdale, became public in February.

By February 1865, Lee had become the South’s last remaining hope. The Richmond Examiner, which opposed arming slaves, imagined that “in the present position” of affairs, “the country will not venture to deny to General Lee anything he may ask for.” The Richmond Sentinel predicted that “[w]ith the great mass of our people, nothing more than this letter [to Congressman Barksdale] is needed to settle every doubt or silence every objection.” But both papers were wrong. Even Lee’s great prestige was not potent enough to determine a question so fundamental to Southern society.

The idea of arming and freeing the slaves horrified many prominent Southerners. “If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong,” objected Howell Cobb of Georgia. North Carolina Senator William A. Graham blasted the administration’s ideas as “insane proposals” and “confessions of despair.” The Charleston Mercury insisted that African Americans were “inferior” and “prone to barbarism.” It denounced Davis’ “extraordinary suggestion” as “unsound and suicidal” and issued a racist warning that “swaggering buck n——s” would ruin the country. A Galveston, Texas, newspaper repeated the familiar argument that “slavery is the best possible condition for the slave himself” and opposed any “abandonment” of that “foundation principle.” Davis, charged the Richmond Examiner, had adopted “the whole theory of the abolitionist.” Lee did not escape criticism in the course of the controversy, the Examiner arguing that his military genius did not make him “an authority” on moral, social or political questions. It even questioned whether the general could be considered “a ‘good Southerner’”—that is, one who was “thoroughly satisfied of the justice and beneficence of [N]egro slavery.”

A few Confederates were willing to pursue independence without slavery. But most of the leadership elite valued slavery above all else. Although the South was in a truly desperate situation by that juncture, the Confederate Congress delayed on a decision for months, its members unwilling to act. Finally, in March 1865, the House passed a bill sponsored by Congressman Barksdale authorizing the president to call for one-quarter of any state’s male slaves between the ages of 18 and 45. Opposition to the measure was strong in the Senate, and the bill would not have passed had Virginia’s legislature not finally instructed its state’s senators to vote yes.

Even so, this tardy measure referred only to using slaves as soldiers; it emancipated no one. The final clause specified that “nothing in this act shall be construed to authorize a change in the relation which the said slaves shall bear toward their owners.” Freedom, as a reward for service, could come only if individual owners and the states in which they lived allowed it, as had always been the case in the Confederacy.

Davis tried to require a pledge of emancipation from any owner who offered his slave for service. But recruitment proved difficult, as resistance continued to making soldiers of slaves. A small number of black recruits began drilling in Richmond, but since the war soon came to an end, the Confederate proposal to arm and free slaves amounted to nothing. Most Confederate slaveholders did not want to give up slavery.

From a 21st-century vantage point, this refusal seems all the more noteworthy in view of the Richmond administration’s ultra-conservative plans for race relations. When Davis and Benjamin were seeking allies for their measure, they made it clear that freedom would not bring equality. The government would have to emancipate soldiers “as a reward for good services.” But for their families, “serfage or peonage” would not follow until after the war. In this way, Southern whites would “vindicate[e] our faith in the doctrine that the negro is an inferior race and unfitted for social or political equality with the white man.” The Southern states should adjust the status of soldiers’ families “by degrees.”

Davis’ plan envisioned “cautious legislation providing for their ultimate emancipation after an intermediate stage.” While these families remained serfs, the Confederacy could legislate “certain rights of property” and provide legal protection “for marital and parental relations.” These steps would not only improve “our institutions” but also blunt external criticism. No longer could critics point to aspects of slavery “calculated to draw down on us the odium and reprobation of civilized man.”

Thus racism dominated the thinking of even those Confederates willing to consider arming and freeing slaves. Even after emancipation, no dramatic improvement in their social or political status would occur. African Americans might be better off after the war, but in a markedly limited way. Though they were technically free, they would remain inferior and subordinate within society.

Such low expectations were not restricted to the South. Racism, in fact, had always been a national problem. Though today the North is popularly credited with fighting the war for the sake of freedom and equality, such was not the case. This misconception had its origin in postwar cultural battles over the meaning of the Civil War, when Northerners often used emancipation to claim the moral high ground. Lincoln won adulation as the Great Emancipator in the decades following the conflict, and more recently some have argued that he was a “fervent idealist” and “moral visionary” who labored and schemed for racial equality. But during the war years the North shrank from giving a morally inspired answer to the question “What shall we do with the Negro?”

At best, a minority of Northerners adopted racially progressive views, while most of those supporting the Union cause continued to hold racist beliefs. Although Lincoln wanted an end to slavery, neither he nor his party was committed to racial equality. The Northern president was more focused on conciliating Southern whites, to gain their participation in reunion, than on improving the postwar status of African Americans.

A few facts can help to bring into perspective the larger picture of the American view of slavery. The Republican Party came into being to oppose slavery’s expansion, and carefully distanced itself from the abolitionists. When Lincoln took the oath of office in 1861, he gave his support to a proposed constitutional amendment that would have guaranteed the existence of slavery against federal interference forever. This was in accord with his party’s pledge to maintain “inviolate the rights of the States, and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively.” This provision, Lincoln said, was “a law to me.”

Once the conflict started, many Northerners soon concluded that an attack on slavery was necessary to win the war. Moving slowly, Lincoln repeatedly proposed measures of gradual, compensated emancipation. These plans envisioned voluntary action by the states and colonization of the freed slaves somewhere outside the nation. Lincoln particularly urged the border slave states to adopt such measures, as a means of dashing Confederates’ hopes and bringing the war to a speedier end.

He justified the Emancipation Proclamation as a necessary war measure, taken under his authority as commander in chief, to preserve the Union. Thereafter the Republican Party and Republican newspapers, such as The New York Times, stressed that emancipation was a “military expedient,” a “weapon of warfare.” The war was “Still to be Prosecuted for the Restoration of the Union.” Lincoln’s “one fixed aim” was “the salvation of the Republic.” Emancipation and elevation of the slaves were “secondary in importance to the salvation of the Union, and not to be sought at its expense.” Or as Lincoln told Horace Greeley, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union,” and whatever he did about slavery he did “because I believe it helps to save the Union.”

Many Republicans believed that African Americans would have to remain in a deeply degraded status, deprived of most rights. The Times contemptuously rejected the idea that emancipation would lead to the African American becoming “a voting citizen of the United States.” Blacks were “incapable” of exercising the right of suffrage, and “for many generations to come” suffrage for the freedmen would bring about “the destruction of popular institutions on this continent.” It was “little short of insane” to think otherwise. At the end of 1864 the Times was still declaring that the “black masses of the South, of a voting age, are as ignorant upon all public questions as the driven cattle.”

Lincoln’s views were not quite so negative. He said little throughout the war about elevating freedmen, but a few days before his death he did express a preference for giving the ballot to a few black men—“the very intelligent” and “those who serve our cause as soldiers.” Nevertheless, he did not envision or promote rapid improvement in the practical conditions and social status of the freed people. What he expected was revealed in a letter to General John McClernand that is seldom quoted, since it does not support the idea of Lincoln as a fervent idealist.

Writing on January 8, 1863, Lincoln noted that in his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation he had given Southern states 100 days to return to the Union. Had they returned, they could have avoided emancipation. Even then he was willing to allow “peace upon the old terms” if they acted “at once.” Moreover, the rebelling states “need not to be hurt” by his proclamation. “Let them adopt systems of apprenticeship for the colored people, conforming substantially to the most approved plans of gradual emancipation, and, with the aid they can have from the general government, they may be nearly as well off, in this respect, as if the present trouble had not occurred.”

This idea of apprenticeships, or “temporary arrangements” (as he also called it), was a fundamental part of Lincoln’s thinking about the postwar future. When he issued his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction at the end of 1863, he sought to reassure white Southerners. He would not object to Southern states adopting measures for the freed people that “shall recognize and declare their permanent freedom, provide for their education, and which may yet be consistent, as a temporary arrangement, with their present condition as a laboring, landless, and homeless class.” He explained that he feared “confusion and destitution” resulting from emancipation and would acquiesce in “any reasonable temporary State arrangement” for the former slaves. Southern whites, the “deeply afflicted people in those States,” might be “more ready to give up the cause of their affliction [slavery], if, to this extent, this vital matter be left to themselves.”

Looking past the war, Lincoln wanted to engage Southerners in reconstruction, to induce them to participate rather than resist at every turn. For this reason he consistently reiterated his view that formerly rebellious states should be readmitted to the Union promptly. He did not call for changes in their constitutions, as the majority in Congress felt was necessary, and he staunchly backed his “ten-percent” government in Louisiana, despite the fact that it was widely criticized and had done little to improve the status of African Americans.

In fact, in his desire to appeal to Southern whites and respect states’ rights, Lincoln supported a method of ratifying the 13th Amendment that would have made its success doubtful. Charles Sumner and other advocates of black rights feared that the defeated South would block the 13th Amendment. The Confederacy had more than enough states to defeat it, and a few states in the Union voted heavily Democratic and were unlikely to support the measure. For that reason Sumner argued that ratification should be determined only by the loyal states. In his last public statement, on April 11, 1865, Lincoln demurred, saying “such a ratification would be questionable, and sure to be persistently questioned.” On the other hand, “a ratification by three-fourths of all the States would be unquestioned and unquestionable.”

A more detailed analysis of Lincoln’s policies augments this picture considerably, but the larger point about American society in 1865 is already clear. Racism pervaded the social landscape in both North and South. Although the war settled the question of secession vs. union, it failed to bring equal rights to African Americans. Before 1865 had passed, three Northern states—Connecticut, Wisconsin and Minnesota, all of which had very few black residents—voted against giving suffrage to African-American men. Equality for blacks would have to be sought in Reconstruction, and it would remain an elusive goal for many decades following the war’s end.

Paul D. Escott is the Reynolds Professor of History at Wake Forest University. This article is adapted from his most recent book, “What Shall We Do With the Negro?”: Lincoln, White Racism, and Civil War.