Facts, information and articles about the Klondike Gold Rush, an event of Westward Expansion from the Wild West

Klondike Gold Rush Facts

Dates

1896-1899

Areas Included

Yukon Region

Klondike Region, Canada

Alaska

Prospectors Involved

100,000 set out. 30,000 arrived in the Klondike

Success Rate

Around 4,000 found gold

Klondike Gold Rush Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Klondike Gold Rush

» See all Klondike Gold Rush Articles

Klondike Gold Rush summary: The Klondike Gold Rush was an event of migration by an estimated 100,000 people prospecting to the Klondike region of north-western Canada in the Yukon region between 1896 and 1899. It’s also called the Yukon Gold Rush, the Last Great Gold Rush and the Alaska Gold Rush.

Gold was discovered in many rich deposits along the Klondike River in 1896, but due to the remoteness of the region and the harsh winter climate the news of gold couldn’t travel fast enough to reach the outside world before the following year. Reports of the gold in newspapers created a hysteria that was nation-wide and many people quit their jobs and then left for the Klondike to become gold-diggers.

Because of the harsh terrain and even harsher weather, it took gold rushers a year to reach the Klondike. The long climb over mountainous terrain and frozen rivers, coupled with the intense cold and frequent snowstorms, made for a long and arduous journey. Each of prospector was told they’d need at least enough food for a year by authorities in Canada so they wouldn’t starve.

In the summer of 1898, gold rushers arrived in the Klondike region by the thousands. Around 30,000 of the 100,000 or so prospectors that set out for the Klondike actually made it there. Many gave up to due to the difficulties of the journey and returned home; some were not able to survive the extreme temperatures and died. Those that made it to the Klondike still had their work cut out for them, as the gold was not easy to find or extract.

Mining was challenging due to pretty unpredictable distribution of gold and digging was slowed by permafrost. Because of this, there were minors that decided to buy and sell their claims so they could build an investment on the backs of others. Along the routes different towns sprung up and where given the name ‘boom towns.’

Of the 30,000 that arrived in the Klondike, only approximately 4,000 actually found gold. Some set up and sold claims rather than digging for gold themselves. Along the Klondike river, boom towns formed that were supported by the miners. Those that found gold spent their time and money in saloons, while those that found nothing continued to labor. In 1899, miners received news that gold had been discovered in Nome and that it was much easier to get, causing the departure of the majority of the miners and the decline of the boom towns.

Articles Featuring Klondike Gold Rush From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

Klondike Gold Rush

On August 16, 1896, George Washington Carmack and two Indian friends in the Yukon pried a nugget from the bed of Rabbit Creek, a tributary of Canada’s Klondike River, and set in motion one of the most frenzied and fabled gold rushes in history. Over the next two years, at least 100,000 eager would-be prospectors from all over the world set out for the new gold fields with dreams of a quick fortune dancing in their heads. Only about 40,000 actually made it to the Klondike, and precious few of them ever found their fortune.

Swept along on this tide of gold seekers was a smaller and cannier contingent, also seeking their fortunes but in a far more practical fashion. They were the entrepreneurs, the men and women who catered to the Klondike fever.

George Carmack, the man who began it all, was neither a die-hard prospector nor a keen businessman. The California native was simply in the right place at the right time. Not that this son of a Forty-Niner had anything against being rich. But, like most of the white men who drifted north in the 1870s and ’80s, he came as much for the solitude as for the gold.

There had been rumors of gold in the Yukon as far back as the 1830s, but little was done about it. The harsh land and harsher weather, plus the Chilkoot Indians’ jealous guarding of their territory, effectively kept out most prospectors–until 1878, when a man named George Holt braved the elements and the Indians and came back with nuggets impressive enough to make other prospectors follow his lead. By 1880, there were perhaps 200 miners panning fine placer gold from the sandbars along the Yukon River.

In 1885, gold was found in paying quantities on the bars of the Stewart River, south of the Klondike River. The next year, coarse gold was found on the Forty Mile River, and a trading post, called Fortymile, then sprang up where the river joins the Yukon River. In 1893, a little farther down the Yukon, in Alaska, two Russian half-bloods hit pay dirt that produced $400,000 a year in gold, and spawned the boom town of Circle City. Known as ‘The Paris of Alaska,’ it boasted two theaters, eight dance halls, 28 saloons, a library and a school. But when news of the strike on Rabbit Creek (soon to be renamed Bonanza Creek) reached the citizens of Circle City, they decamped in droves. Only a year before Carmack’s lucky find, Canada had created the Yukon District as an administrative subunit within the Northwest Territories, and construction had begun on Fort Constantine (across from Fortymile), the first North-West Mounted Police post in the Yukon. So law enforcement was in place just in time to greet the droves of prospectors who would soon be stampeding to the Klondike region of the Yukon District, which would become a separate territory on June 13, 1898.

Like his Indian friends, George Carmack believed in visions. Shortly before his dramatic discovery, he had a vision in which two salmon with golden scales and gold nuggets for eyes appeared before him. So lacking in mercenary impulses was he that he interpreted this as a sign that he should take up salmon fishing. And that’s just what he was doing, along with his friends Skookum Jim and Tagish Charley, when a determined prospector named Robert Henderson floated down from upriver and, in keeping with the prospector’s code, told George about the ‘color’ he’d found on a creek he dubbed Gold Bottom Creek. But, he warned, glaring at Jim and Charley, he didn’t want any ‘damn Siwashes’ staking claims there.

The three friends didn’t like Henderson’s attitude, and for two weeks they ignored his lead. Then, with nothing better to do, they meandered over to check out Henderson’s claim. Henderson insulted the Indians again by refusing to sell them tobacco. Indignant, George, Jim and Charley left and set up camp on Rabbit Creek. While cleaning a dishpan, one of the three unearthed the thumb-sized chunk of gold that set the great rush in motion. Probably because of the insults, Carmack didn’t bother to hike the short distance back to Henderson’s diggings to tell him of the strike. Instead, he headed downriver the 50 or so miles to Fortymile to record his claim, and Jim’s and Charley’s. On the way, he bragged to everyone he saw of his good luck.

Most of the old-timers just scoffed. Carmack had made’strikes’ before that amounted to nothing, earning him the nickname ‘Lying George,’ so they put little stock in this new bonanza of his. But a few cheechakos (newcomers) went to investigate, and the word spread. Within five days, the valley was swarming with prospectors. By the end of August, the whole length of Bonanza Creek was staked out in claims; then an even richer vein was found on a tributary that became known as Eldorado Creek.

If all this had come about early in the year, the news would have reached civilization within a few weeks. But winter was already closing in. Once the rivers froze and the heavy snows fell, communication with the outside was nearly impossible. William Ogilvie, a Canadian government surveyor, sent off two separate messages to Ottawa, telling of the magnitude of the strike, but both were lost in the bureaucratic shuffle.

So it wasn’t until the following July (1897), when steamships from Alaska docked in San Francisco and Seattle–disgorging 68 ragged miners carrying more than 2 tons of gold in suitcases, boxes, blankets and coffee cans–that the outside world caught the Klondike fever.

The fever quickly reached epidemic proportions. Like a worn-down body that’s susceptible to any disease that comes along, the country was particularly susceptible just then to gold fever. The amount of gold in circulation had dropped, helping to cause the deep economic depression that had been eating at the United States for 30 years. The Pacific Northwest had been hit especially hard. People were tired of being poor; many who had jobs quit them for the promise of greater rewards. Streetcar drivers abandoned their trolleys; a quarter of the Seattle police force walked out; even the mayor resigned and bought a steamboat to carry passengers to the Klondike.

Those who had no jobs mortgaged their homes or borrowed the $500 or so needed to buy an ‘outfit’–a stove, tent, tools, nails and enough supplies to last a year. A proper outfit tipped the scales at nearly 2,000 pounds–though one fast-talking salesman began hawking a valise that he claimed contained a year’s worth of desiccated food and weighed only 250 pounds!He was just one of a growing number of enterprising citizens who realized there was a fortune to be made right here at home, simply by selling a product, however dubious in value, with the name Klondike attached. There were Klondike medicine chests, Klondike electric gold pans, Klondike mining schools, a Klondike bicycle, even a portable Klondike house purported to be ‘light as air’ when folded up–a doubtful claim, considering it featured a double bed and an iron stove.

Inventors dreamed up devices that promised to make the task of digging gold positively pleasant. Nikola Tesla, one of the pioneers of electricity, promoted an X-ray machine that would supposedly detect precious metals beneath the ground without all the trouble of digging. A Trans-Alaskan Gopher Company proposed to train gophers to claw through frozen gravel and uncover nuggets. Clairvoyants touted their abilities to pinpoint rich lodes of gold. Several ventures were underway to invade the Klondike by balloon.

Even as all these cockeyed schemes and services were being offered, there was one crucial commodity that was in desperately short supply–transportation. There weren’t nearly enough ships in the Northwest to handle the stampede of gold seekers–2,800 from Seattle alone in a single week. Everything that floated was pressed into service–ancient paddlewheelers and fishing boats, barges, coal ships still full of coal dust. All were overloaded, and many unseaworthy; they were dubbed ‘floating coffins,’ and all too often they lived up to the name.

A few ships sailed around the Aleutians and through the Bering Sea to St. Michael, Alaska, on Norton Sound. The passengers could then take riverboats upstream from the Yukon River delta to the gold fields, a 1,600-mile trip on the winding Yukon. But not many Klondikers could afford the $1,000 fare. Most boats went only as far as Skagway in the Alaska Panhandle, where the passengers and their outfits were unceremoniously dumped on the mile-wide tidal flats. If the Klondikers weren’t ready to turn back by then, there was plenty of adversity ahead to change their minds. Skagway itself was no beach resort. It was, in fact, a grimy anarchic tent town that a visiting Englishman described as ‘the most outrageously lawless quarter I have ever struck. ‘ There was a saloon or a con man, or both, on every corner, and gunfire in the streets was so commonplace as to be mostly ignored. The most famous of the con men was Jefferson Randolph (‘Soapy’) Smith, the ‘Uncrowned King of Skagway,’ who ran the town’s underworld until he died in a July 8, 1898, shootout.

But even in this chaotic setting, legitimate businesses flourished. What the would-be miner needed by now was some way of getting his outfit to the gold fields, so anyone with a wagon and a team or a few mules could do well for himself–or herself. Harriet Pullen, a widow with a brood of children, arrived in Skagway with $7 to her name, but parlayed it into a fortune by driving a freight outfit all day and, at night, baking apple pies in pans hammered out of old tin cans. She became the town’s most distinguished citizen. Joe Brooks, one of the most successful ‘packers,’ owned 335 mules and raked in $5,000 a day–far more than most men earned in a year. In keeping with the nature of the town, he wasn’t overly scrupulous; if he was hauling equipment for one customer and got a more tempting offer, he’d simply dump the first shipment alongside the trail.

In addition to the boat passage up the Yukon, there were at least five trails being touted as the best route to the gold fields. But three of those were so long and hazardous that only a few men ever succeeded in reaching the Klondike alive on them. The two most heavily traveled routes began in Skagway and the neighboring town of Dyea.

In the fall of 1897, the more popular was the 550-mile Skagway Trail over White Pass. At first glance, it seemed the less demanding of the two; it climbed more gradually, which meant that–in theory at least–pack animals could negotiate it. Once on the trail, miners found it nowhere near as easy as it looked. It led them through mudholes big enough to swallow an animal, over sharp rocks that tore at horses’ legs and hooves, across cliffs of slippery slate, where the trail was a scant 2 feet wide and a 500-foot drop awaited any animal–or miner–who made a misstep.

Most of the pack animals were broken-down horses that would have been lucky to survive the trek under the best of conditions. Overburdened as they were by miners desperate to get their outfits over the pass as quickly as possible, they didn’t stand a chance. Before long, the trail was christened ‘Dead Horse Trail’ after the many carcasses that littered it. As writer Jack London described it, ‘The horses died like mosquitoes in the first frost and from Skagway to Bennett they rotted in heaps. ‘ If a horse gave out in the middle of the narrow trail, no one bothered to drag it away; it was simply ground into the earth by the endless parade of feet and hooves. Faced with this nightmare of mud and mayhem, thousands of miners turned back, sold their outfits, and retreated to civilization with spirits broken and pockets empty. But thousands more slogged on and reached Lake Bennett, the headwaters of the Yukon River. Only a very few made it before cold weather choked the lake and the river with ice. The rest were marooned on the shores of the lake until spring.

When heavy snow made the Skagway Trail impassable, the growing flow of gold seekers switched to the Dyea Trail, also called the ‘Poor Man’s Trail’ because it was too steep for pack animals. But even there, the Klondikers were forced to hire Indian packers, at as much as 50 cents a pound, or else lug their outfits themselves, 100 pounds at a time, leaving each load alongside the trail somewhere, then going back for the next load and so on, over and over; by the time a miner transferred his whole outfit to the far side of the pass, he might have walked the 40-mile trail 30 or 40 times, and spent three months doing it. The most daunting part was Chilkoot Pass, which lay at the top of a nearly vertical slope, four miles long. An unbroken stream of Klondikers toiled up it day and night–a total of 22,000 in the winter of 1897. It was an agonizing climb, and the worst of it was that each man had to repeat it again and again until his entire outfit was carried over the pass. The only consolation was that, between loads, he got a free ride down the snowy slope on the seat of his pants.

For the entrepreneur, there was money to be made here, too. Several roadhouses went up along the trail, including the grandly named Palmer House at the foot of the pass. Most were no more than large tents or ramshackle wooden structures, but they offered hot meals and a place to sleep, even if it was only on the floor. On the worst stretches of trail, an enterprising man could bridge a mudhole with logs and charge a fee to each miner who crossed. At the pass itself, several men laboriously chopped 1,500 steps in the hard-packed snow, then collected so much money in tolls that the route was dubbed ‘the Golden Stairs.’

Like the travelers on the Skagway Trail, those who crossed Chilkoot Pass ended up in a vast tent city on the shores of Lake Bennett and spent long months there, waiting for the thaw. Most passed the time cutting trees from the surrounding hillsides and sawing them into planks for boats that, in the spring, would take them down the Yukon River to the gold fields, still 500 miles away.

At the end of May 1898, the ice broke, and a flotilla of flimsy, handmade craft set off downriver, only to encounter one last deadly obstacle–Miles Canyon. The ferocious rapids in the canyon smashed boats to splinters on the rocks, so many of them that the North-West Mounted Police decreed that every boat had to be inspected and then guided through by a competent pilot. A few experienced sailors got substantial grubstakes by taking boats through the canyon at up to $100 a trip. Among them was Jack London, who netted a cool $3,000.

The boats had one more stretch of rapids to endure, and then the Yukon stayed pretty tame all the way to Dawson City. Before the fall of 1896, Dawson didn’t exist. When gold was discovered on Bonanza Creek, a tent camp went up at the junction of the Klondike and Yukon rivers. By the following summer, its population had grown to 5,000. A year later, after the Klondike fever spread worldwide, it swelled to 40,000–becoming one of the largest cities in Canada. Thanks to the North-West Mounted Police, it was a far more law-abiding town than Skagway, though there were only 19 Mounties in the Yukon in late 1896. By November 1898, however, there would be 285. In the summer of 1897, the Mounties’ new headquarters became Fort Herchmer, at Dawson. Detachments were established atop White and Chilkoot passes. The Mounties’ main function was collecting customs duty for supplies brought into Canada by the gold seekers. In addition, between 1898 and 1900, a 200-man militia outfit, known as the Yukon Field Force, also operated in the area, helping the North-West Mounted Police to guard gold shipments, banks and prisoners.

Despite the presence of law enforcement officers, the flood of new gold seekers still generally found the Yukon just another stage of Hell. After a miserable, cramped sea voyage, after a weary trek across mosquito-infested bogs and over glaciers, after interminable months spent courting frostbite in a flimsy tent, they had finally reached the fabled gold fields, only to find that all the land along every gold-bearing creek had long since been staked out. For many of them, this was the final blow; they sold their outfits and headed home. Those who stayed felt lucky to find jobs in the bustling town or working someone else’s claim for $17 a day in gold dust–good wages on the outside, but barely a living here.

But if Dawson dashed the dreams of the gold seekers, for those few who’d had the foresight to bring goods to sell, the town was a gold mine. The old timers who had spent the winter there, subsisting on a diet of beans and biscuits at best, were eager to trade their gold for luxuries like eggs, fruit, writing paper, or just a bit of news from the outside. One newcomer sold a months-old copy of a Seattle newspaper, soaked with bacon grease, for $15.

As Dawson grew, so did the fortunes of those who made the right business decisions. While most men devoted their energies to working a single claim, Alex McDonald, a Nova Scotian whose shy, awkward manner belied a canny business sense, bought up the claims of discouraged miners and hired others to work them for him. He earned $5 million and the title ‘King of the Klondike’ without ever lifting a pick or shovel. The ‘Queen of the Klondike,’ Belinda Mulroney, took another route to riches. She arrived in the Klondike in the spring of 1897 with $5,000 worth of cotton clothing and hot-water bottles, which she sold for $30,000. Next, she opened a lunch counter and, with the profits, hired men to build cabins that sold before the roofs were on. A successful roadhouse near the gold fields followed. But that was not ambitious enough for Mulroney. She went on to build the grandest hotel in the Klondike–the Fairview, which boasted brass beds, fine china, cut-glass chandeliers and chamber music in the lobby, even electricity generated by the engine of a yacht anchored in the harbor.

For a brief time, Belinda and Big Alex became partners in a scheme to salvage the cargo of a wrecked steamboat. Crafty Alex got to the wreck first and made off with the most valuable supplies, leaving Belinda only some cases of whiskey and a large inventory of rubber boots. ‘You’ll pay through the nose for this,’ she promised, and, as usual, she got her way. When the spring thaw turned the ground in the gold fields to mush, McDonald was in dire need of boots for his men, and Mulroney was happy to provide them–at $100 a pair. Mulroney went on to become the only women manager of a mining company, the largest in Yukon Territory.

But life in Dawson had become too tame for the Queen of the Klondike. When news came of a bigger gold strike in Nome, Alaska, she headed down the Yukon to conquer this new region. So did most of the population of Dawson. During one week in August 1899, 8,000 people deserted Dawson for the beaches of Nome. Just three years after the discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek, the great gold rush was over. Of the 40,000 people who reached Dawson, only about 15,000 actually had the grit to work the gold fields; of those, about a quarter actually unearthed any gold, and only a handful of them became wealthy. Of that handful, a very few managed to hang onto their wealth. Most gambled or drank it away.

Big Alex McDonald became obsessed with buying up unwanted claims and eventually found himself stuck with a lot of worthless real estate. He died broke and alone. Belinda Mulroney married a fake French count and lived in style for several years, until her husband invested her money in a European steamship company–on the eve of World War I, which put an end to merchant shipping. She, too, died nearly penniless.

Tagish Charley sold his claim, spent the proceeds lavishly, and died an alcoholic. Shookum Jim wasn’t content with the riches he’d made; he spent the rest of his life searching in vain for another strike equal to the one on Bonanza Creek. Ironically, George Carmack, who had never had much use for money, was one of the few miners who managed to keep and even increase his fortune by investing in businesses and real estate. He was still a wealthy man when he died in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1922.

Although the heyday of the individual prospector ended with the rush to Alaska in 1899, a more subtle and more profitable exploitation of the Klondike began. The new railroad line from Skagway was completed that summer, opening up the area to the big mining companies with their mechanical dredges, which did the work of hundreds of miners. They continued to mine the land the gold seekers had abandoned for another 50 years, and unearthed millions more in gold. Once again, the men of business had triumphed.

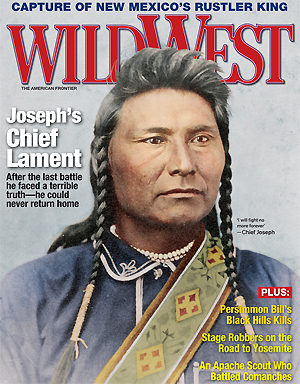

This article was written by Gary L. Blackwood and originally appeared in the August 1997 issue of Wild West.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!