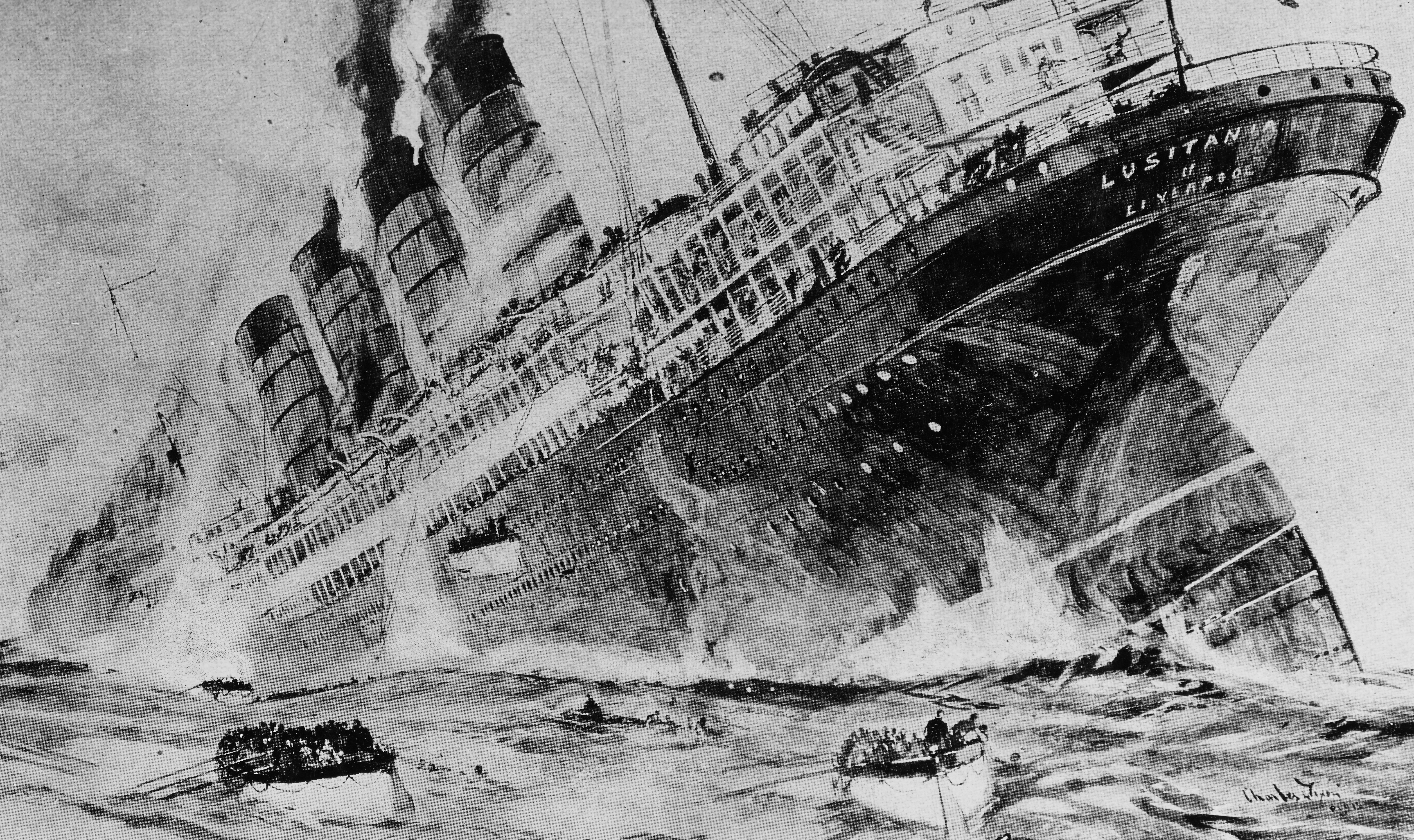

Shortly after noon on a drizzly spring day in 1915, the Cunard liner Lusitania backed slowly away from Pier 54 on New York’s Lower West Side. It was Lusitania‘s 202nd Atlantic crossing, and as usual the luxury liner’s sailing attracted a crowd, for the 32,500-ton vessel was one of the fastest and most glamorous ships afloat. In the words of the London Times, she was ‘a veritable greyhound of the seas.’

Passengers, not yet settled in their accommodations, marveled at the ship’s size and splendor. With a length of 745 feet, she was one of the largest man-made objects in the world. First-class passengers could eat in a two-story Edwardian-style dining salon that featured a plasterwork dome arching some thirty feet above the floor. Those who traveled first class also occupied regal suites, consisting of twin bedrooms with a parlor, bathroom, and private dining area, for which they paid four thousand dollars one way. Second-class accommodations on Lusitania compared favorably with first-class staterooms on many other ships.

People strolling through nearby Battery Park watched as three tugs worked to point the liner’s prow downriver toward the Narrows and the great ocean beyond. While well-wishers on the pier waved handkerchiefs and straw hats, ribbons of smoke began to stream from three of the liner’s four tall funnels. Seagulls hovered astern as the liner slowly began to pick up speed.

The early years of the twentieth century belonged to the great ocean liners, and Lusitania was one of the elite. A Scotsman who was present at her launching in 1907 recalled his awe at the sight:

Was it the size of her, that great cliff of upperworks?… Was it her majesty, the manifest fitness of her to rule the waves? I think what brought the lump to the boy’s throat was just her beauty, by which I mean her fitness in every way; for this was a vessel at once large and gracious, elegant and manifestly efficient. That men could fashion such a thing by their hands out of metal and wood was a happy realization.

In 1908, on one of her first Atlantic crossings, Lusitania broke the existing transatlantic speed record, making the run from Liverpool to New York in four and one-half days, traveling at slightly more than twenty-five knots. Like her sister ship, Mauritania, she could generate sixty-eight thousand horsepower in her twenty-five boilers. Lusitania was also versatile, for the government subsidy that helped pay for her construction required her to have features that would facilitate her conversion to an armed cruiser if necessary. The liner’s engine rooms were under the waterline, and she incorporated deck supports sufficient to permit the installation of six-inch guns.

It was May 1, 1915, and Lusitania, with 1,257 passengers and a crew of 702, was beginning a slightly nervous crossing. War was raging in Europe, and although no major passenger liner had ever been sunk by a submarine, some passengers were uneasy. The German embassy had inserted advertisements in a number of American newspapers warning of dangers in the waters around the British Isles.

Because this warning appeared only on the day of sailing, not all of those who boarded Lusitania saw it. Yet for travelers with an apprehensive turn of mind, there were alternatives to the Cunarder. The American Line’s New York, with space available, sailed the same day as Lusitania, but she required eight days to cross the Atlantic as opposed to Lusitania‘s six.

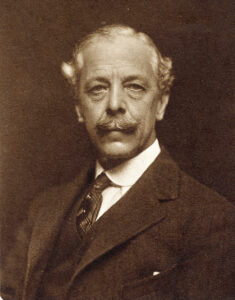

Despite the warning posted by the German embassy, Lusitania‘s captain was not nervous. When Captain William Turner was asked about the U-boat threat he reportedly laughed, remarking that ‘by the look of the pier and the passenger list,’ the Germans had not scared away many people.

By the spring of 1915 the land war in Europe had settled into a bloody stalemate, but one in which the Central Powers held the advantage. A decisive German victory at Tannenberg had all but taken czarist Russia out of the war. The initial German thrust for Paris had been repulsed, but even as Lusitania sailed, the British were being mauled in the month-long Second Battle of Ypres.

The war at sea, however, was a different matter. The Royal Navy’s numerical superiority made it perilous for the German fleet to venture out of port and enabled the Allies to move troops and materiel by sea. Most important of all, Allied control of the sea had cut the Central Powers off from overseas supplies of food and raw materials. When the increased range of shore-based guns prevented the British from maintaining a traditional offshore blockade of German ports, the Royal Navy mounted a long-range blockade instead. British cruisers patrolled choke points well away from German ports, halting all vessels suspected of carrying supplies to Germany and enlarging the traditional definition of contraband to include even raw materials and food.

Not all contraband was headed for Germany. Lusitania carried some forty-two hundred cases of Remington rifle cartridges destined for the Western Front. Her cargo also included fuses and 1,250 cases of empty shrapnel shells. Although the Germans had no knowledge of this cargo, it is clear that British authorities were prepared to compromise Lusitania‘s nonbelligerent status as a passenger liner for a small amount of war materiel.

The growing effectiveness of the Allied blockade had forced Germany to take drastic measures. Germany’s most promising offensive weapon at sea was the submarine, but international law of the time prohibited its most effective employment. If a submarine encountered a vessel that might belong to an enemy or might be carrying contraband, the U-boat had to surface, warn her intended victim, and ‘remove crew, ship papers, and, if possible, the cargo’ before destroying her prey.

In response to Britain’s unilateral redefinition of a naval blockade, Germany issued a proclamation of its own, declaring the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland to be a war zone. From February 18, 1915, on, Berlin had declared, enemy merchant vessels found within the zone would be subject to destruction without warning.

The day before Lusitania sailed from Pier 54, U-20, skippered by thirty-two-year-old Kapitänleutnant (Lt. Cmdr.) Walther Schwieger, left the German naval base at Emden on the North Sea. Schwieger’s orders were to take U-20 around Scotland and Ireland to the Irish Sea. There he was to operate in the approaches to Liverpool for as long as his supplies permitted. His orders allowed him to sink, with or without warning, all enemy ships and any other vessels whose appearance or behavior suggested that they might be disguised enemy vessels. The British were known to dispatch ships under neutral flags.

Submarine warfare was still in its infancy, and Germany had only eighteen seagoing subs, of which only about one-third could be on station at any one time. Schwieger’s U-20 displaced just 650 tons, making it about half the size of a fleet submarine in World War II. The boats were crowded and damp, and the eight torpedoes they carried were often unreliable. But the men who commanded the U-boats included some of the boldest officers of an elite service, and U-20 had a reputation as a ‘happy’ ship. The scion of a prominent Berlin family, Schwieger was popular with his officers and crew. One of his colleagues recalled him as ‘tall, broad-shouldered, and of a distinguished bearing, with well-cut features, blue eyes and blond hair–a particularly fine-looking fellow.’

On May 3, U-20‘s fourth day at sea, Schwieger spotted a small steamer just north of the Hebrides. Although the vessel was flying Danish colors, Schwieger concluded that she was British and fired a torpedo at her from three hundred meters. The torpedo misfired and his quarry escaped, but the incident said much about Schwieger’s interpretation of his orders. He would not risk his boat by questioning possible neutrals. Rather, he would make full use of his authorization to sink ships without warning.

On the sixth day of his patrol, Schwieger rounded the southern tip of Ireland and entered the Irish Channel. There he encountered a small schooner, Earl of Lathom, under sail. Schwieger considered her so minimal a threat that he surfaced, allowed the schooner’s five-man crew to abandon ship, and destroyed the vessel with shellfire. Later the same day he attacked a three-thousand-ton steamer flying Norwegian colors, but the single torpedo he fired missed.

The next day, May 6, brought better fortune. That morning U-20 surfaced and pursued a medium-sized freighter, bringing her to a halt with gunfire. Schwieger believed in shooting first and identifying later, but in this case he was vindicated, for his prey turned out to be a British merchantman, Candidate, out of Liverpool. Schwieger dispatched her with a torpedo. That same afternoon U-20 sighted another ship of undetermined nationality. Schwieger stopped her with one torpedo and watched as her crew took to the boats. He then sent her to the bottom with a second torpedo. This victim was Centurion, sister ship to the fifty-nine-hundred-ton Candidate.

After sinking Centurion, Schwieger made a critical decision. Although his orders called for him to press on to Liverpool, he had only three torpedoes left and was near the end of his cruising range. Schwieger would expend one more torpedo in his current operational area and then begin the return voyage, confident of finding targets en route for his remaining two torpedoes.

Although Lusitania had left New York City with much of the pomp of a peacetime crossing, not all was well aboard the liner. To conserve coal, six of the ship’s twenty-five boilers had been shut down, effectively reducing her top speed from twenty-five to twenty-one knots. Perhaps most important, there was a shortage of experienced seamen on Lusitania. The Royal Navy had called up most reservists, leaving Cunard to recruit crewmen as best it could.

Nevertheless, the ship was in the hands of one of the most experienced skippers on the Atlantic run. Captain Turner, sixty-three, had been assigned to Lusitania just before her previous crossing, but he was a veteran commander. One of his officers, Albert Worley, saw his skipper as a typical British merchant captain, ‘jovial yet with an air of authority.’ The son of a sea captain, Turner had signed aboard a clipper as a cabin boy at age thirteen and had served as a junior officer on a variety of sailing vessels. Some believed that Turner’s blunt speech and unpolitic manner were liabilities, but no one questioned his seamanship. In 1912, while captain of Mauritania, he had won the Humane Society’s medal for rescuing the crew of the burning steamer West Point.

Much would later be made of Turner’s seeming lack of concern about the submarine menace. But the skipper knew that no ship the size and speed of Lusitania had ever fallen victim to a U-boat. Even steaming at a reduced speed, Lusitania could outrun any submarine, underwater or on the surface.

The liner plowed ahead on its northeasterly course, averaging about twenty knots. The normally festive atmosphere on board had been dampened somewhat by the war; indeed, Cunard had obtained a full passenger list only by reducing some fares. The only gilt-edged celebrity on board was multimillionaire Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, en route to Britain for a meeting of horse breeders. Vanderbilt was fortunate in more than his inherited wealth; three years earlier he had booked passage on Titanic‘s maiden voyage but had missed the fatal cruise because of a change in plans. Other first-class passengers included Broadway impresario Charles Frohman, scouting for new theatrical offerings, and Elbert Hubbard, the homespun writer of inspirational essays such as ‘A Message to Garcia.’

On Sunday, May 2, the first day out, Captain Turner conducted church services in the main lounge. The following day found the liner off Newfoundland’s Grand Banks. On May 4, Lusitania was halfway to her destination. The weather was fine, and Turner had reason to anticipate an easy crossing. Even so, the war was never entirely forgotten. On the morning of May 6, as the ship prepared to enter Berlin’s proclaimed war zone, some passengers were startled by the creak of lifeboat davits. Early risers on B deck saw the Cunard liner’s lifeboats being uncovered and swung out over the sides of the ship, where they would remain during the final, most dangerous portion of the voyage.

That evening Turner was called away from dinner to receive a radio message from the British Admiralty that warned of submarine activity off the southern coast of Ireland. There was no elaboration; the Admiralty did not mention the recent losses of Candidate and Centurion. Forty minutes later, however, came an explicit order to all British ships: ‘Take Liverpool pilot at bar, and avoid headlands. Pass harbors at full speed. Steer midchannel course. Submarines off Fastnet.’

Lusitania acknowledged the message and continued on course. She was now about 375 miles from Liverpool, making twenty-one knots. Turner ordered all watertight doors closed except those providing access to essential machinery, and he doubled the watch. Stewards were instructed to see that portholes were secured and blacked out.

May 7 began with a heavy fog, and Lusitania‘s passengers awakened to the deep blasts of the liner’s foghorn. Turner maintained a course of eighty-seven degrees east but because of the fog ordered a reduction in speed to eighteen knots. The skipper was timing his arrival at the Liverpool bar for high tide so that, if no pilot was immediately available, he could enter the Mersey River without stopping.

Some 130 miles east, in his surfaced boat, Schwieger was wondering whether, given the poor visibility, he should continue on station. He recalled:

We had started back for Wilhelmshaven and were drawing near the Channel. There was a heavy sea and a thick fog, with small chance of sinking anything. At the same time, a destroyer steaming through the fog might stumble over us before we knew anything about it. So I submerged to twenty meters, below periscope depth.

About an hour and a half later…I noticed that the fog was lifting…. I brought the boat to the surface, and we continued our course above water. A few minutes after we emerged I sighted on the horizon a forest of masts and stacks. At first I thought they must belong to several ships. Then I saw it was a great steamer coming over the horizon. It was coming our way. I dived at once, hoping to get a shot at it.

Until midday, Turner had taken most of the measures that a prudent captain would be expected to take during wartime. On the fateful afternoon of May 7, however, he reverted to peacetime procedures. The coast of Ireland was in clear view at 1 p.m., but Turner was uncertain of his exact position. Ignoring Admiralty orders to zigzag in dangerous waters, to maintain top speed, and to avoid headlands, Turner changed Lusitania’s course toward land to fix his position. At 1:40 p.m. he recognized the Old Head of Kinsale, one of the most familiar headlands of the Irish coast. With cottages on the coast clearly visible to her passengers, Lusitania swung back toward her earlier course of eighty-seven degrees east and headed toward her reckoning.

The change of course involved two turns. In Schwieger’s recollection:

When the steamer was two miles away it changed its course. I had no hope now, even if we hurried at our best speed, of getting near enough to attack her…. [Then] I saw the steamer change her course again. She was coming directly at us. She could not have steered a more perfect course if she had deliberately tried to give us a dead shot….

I had already shot away my best torpedoes and had left only two bronze ones–not so good. The steamer was four hundred yards away when I gave an order to fire. The torpedo hit, and there was a rather small detonation and instantly after a much heavier one. The pilot was beside me. I told him to have a look at close range. He put his eye to the periscope and after a brief scrutiny yelled: ‘My God, it’s the Lusitania.’

U-20‘s torpedo, carrying three hundred pounds of explosives in its warhead, struck between the first and second funnels, throwing a huge cloud of debris into the air. Turner, who had been in his cabin when the torpedo wake was spotted, rushed to the bridge. Survivors later testified almost unanimously that a second, heavier explosion followed. Power was cut off throughout the ship, preventing Turner from communicating with the engine room and trapping some people belowdecks. Passenger Margaret Mackworth and her father were about to step into an elevator when they felt the ship tremble from Schwieger’s detonating torpedo. Both stepped back, an action that undoubtedly saved their lives.

Above, confusion was rampant. Passengers rushed to the boat deck, only to be told that the ship was safe and that no boats need be launched. Most life rafts were still lashed to the decks. Passengers and crewmen alike milled about; although Lusitania carried ample lifeboats, passengers had never been informed to which boat they were assigned in case of an emergency. Charles Lauriat, a Boston bookseller, later noted that as many as half the passengers had put on their life jackets improperly.

The ship immediately took on a heavy list to starboard that made it impossible to lower boats from the port side. The inexperienced crew could not cope. When Third Officer Albert Bestic reached the No. 2 lifeboat on the port side, he found it filled with women–most in full-length skirts–but only one crewman was available to man the davits. When Bestic, the crewman, and a male passenger attempted to lower the boat, there was a sharp crack. One of the guys had snapped, dropping the bow of the lifeboat and spilling its passengers against the rail and into the sea.

Three years earlier, those aboard Titanic for whom there were not enough lifeboats had had some two hours in which to stare into their icy grave. Aboard Lusitania, the imminence of the disaster left little time for contemplation. For instance, shortly after the torpedo struck, second-class passenger Allan Beatty slid across the entire width of the deck, caught the side of a collapsible raft, and still almost drowned as water poured over the rail.

Although Turner never gave an order to abandon ship, individual officers began loading boats on their own initiative. But the fact that the liner was still underway made it difficult to launch even the starboard boats. Several capsized, spilling their occupants into the water. Only eighteen minutes after Schwieger’s torpedo struck, Lusitania sank with a roar that reminded one passenger of the collapse of a great building during a fire. Hundreds of passengers went down with her, trapped in elevators or between decks. Hundreds of others were swept off the ship and drowned in the roiled waters. Because Lusitania was nearly eight hundred feet long, her black-painted stern and four great screws were still visible to horrified onlookers on shore at Kinsale when the liner’s bow struck bottom at 360 feet.

Not a ship was in sight when the liner went down; other skippers appear to have taken the submarine warnings more seriously than had Turner. But a stream of fishing boats from nearby Queenstown collected the living and the dead during the afternoon and evening of May 7. More than 60 percent of the people on board died–a total of 1,198–of whom 128 were Americans. About 140 unidentified victims were buried at Queenstown, but the remains of nine hundred others were never found. Of the American celebrities, all three–Frohman, Hubbard, and Vanderbilt–went down with the ship. One survivor recalled, ‘Actuated by a less acute fear or by a higher degree of bravery which the well-bred man seems to feel in moments of danger, the men of wealth and position for the most part hung back while others rushed for the boats.’

Whatever Lusitania may have been carrying as cargo, the death toll aboard the liner ensured that the sinking would become a public relations disaster for Germany. Instead of issuing an apology, however, or at least holding out the promise of an investigation, Berlin first sought to deflect responsibility. Adding insult to injury, thousands of Germans purchased postcards that portrayed Schwieger’s torpedo striking Lusitania, with an inset of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. The newspaper of one of the centrist political parties, Kolniche Volkszeilung, editorialized:

The sinking of the Lusitania is a success of our submarines which must be placed beside the greatest achievements of this naval war…. It will not be the last. The English wish to abandon the German people to death by starvation. We are more humane. We simply sank an English ship with passengers who, at their own risk and responsibility entered the zone of operations.

In Britain, reaction to the sinking was immediate and violent. British officials denied German suspicions that Lusitania was carrying contraband, and in London and Liverpool, mobs attacked German-owned shops. The reaction in the United States was less destructive but more ominous. Former President Theodore Roosevelt denounced the sinking as piracy; to Roosevelt, it was inconceivable that the United States could fail to respond. The press reaction outside the German-American community was almost uniformly condemning. The New York Tribune warned that ‘the nation which remembered the Maine will not forget the civilians of the Lusitania.’ A cartoon in the New York Sun depicted the kaiser fastening a medal around the neck of a mad dog.

The United States was not yet ready for war, however, and amid the indignation there were calls for restraint. But the Lusitania tragedy caused thousands of Americans, heretofore indifferent to the war in Europe, to side with the Allies. On May 12 the British government released a report on German atrocities in Belgium. The report exaggerated the extent of German depredations, but in the aftermath of Lusitania’s sinking most Americans were a receptive audience. The German ambassador in Washington reported that the Lusitania affair had dealt a fatal blow to his efforts to enhance his country’s image.

The foreign reaction was sufficiently disturbing to the German government that Schwieger, on his return to Germany, met with a cool reception. Then U-20‘s log mysteriously disappeared. Typewritten versions of Schwieger’s log, made available after Lusitania survivors had reported a second explosion, included this sentence: ‘It would have been impossible for me…to fire a second torpedo into this crowd of people struggling to save their lives.’

In the diplomatic exchanges that followed the sinking, Germany was for a time intransigent and then issued a statement expressing regret for the loss of American lives. President Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan, resigned his post over the stern tone of Wilson’s notes protesting the German action, arguing that Germany had a right to prevent contraband from going to the Allies and that a ship carrying contraband could not rely on passengers to protect her from attack. But Germany had lost the propaganda war.

On August 19, 1915, while diplomatic notes on the Lusitania affair were still being exchanged, another British liner, Arabic, was torpedoed, with the loss of two American lives. This time the German Foreign Ministry impressed upon the kaiser the seriousness of any rupture with the United States, and Germany promised that no more merchant ships would be torpedoed without warning. The threat of Amercian intervention receded until, more than a year later, the beleaguered Germans believed it was necessary to resume unrestricted submarine warfare to break the British blockade. Berlin’s announcement, on January 31, 1917, that its submarines would’sink on sight’ brought the United States into the war.

Nearly two years had passed between the sinking of Lusitania and President Wilson’s call for a declaration of war. But when Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917, the picture that came to American minds was of the women and children aboard the legendary Cunard liner. Indeed, much of the world seemed prepared to accept the judgment of a British court that responsibility for Lusitania rested exclusively with the Germans, ‘those who plotted and…committed the crime.’

Turner, who survived the sinking of his ship, was roundly criticized for having failed to maintain top speed and for having ignored Admiralty orders to avoid headlands such as the Old Head of Kinsale. He never again took a Cunard liner to sea. As for Schwieger, he went on to become one of Germany’s top U-boat aces, receiving his country’s highest decoration for having destroyed 190,000 tons of Allied shipping. About five weeks after receiving his decoration, however, Schwieger took U-88 on what proved to be his last cruise. The submarine never returned; she apparently struck a mine and went down with all hands.

Although divers attempted to explore the wreck of Lusitania both before and after World War II, only recently has the availability of advanced underwater cameras and robotic vehicles made a thorough examination possible. In August 1993, Dr. Robert Ballard, whose teams had earlier explored Titanic and Bismarck, led an expedition to the wreck of Lusitania. Employing a small submarine and remote-controlled, camera-equipped vehicles, Ballard took extensive photographs, partly in an attempt to explain the mysterious second explosion.

Although the ship lies on her starboard side, with the interior largely collapsed, Ballard had sufficient access to the wreck to determine that the magazine where the cartridges had been stored was undamaged. Nor was there any evidence of a boiler explosion. Given that Schwieger’s torpedo had struck near a coal bunker, and the fact that the wreck is surrounded by spilled coal, Ballard makes a convincing case that the second, fatal blast resulted from an explosion of coal dust in the forward bunkers.

In the eight decades since the torpedoing of Lusitania, the world has passed through two world wars, the Holocaust, Stalin’s purges, and China’s Cultural Revolution. Today, the indignation aroused by the sinking of Lusitania seems almost quaint. By the time of World War II, the idea that any submarine would surface to warn of an impending torpedo attack was ludicrous; the practice of the German, British, and U.S. navies alike was to torpedo ships without warning.

By the standards of his day, however, Schwieger’s action was reprehensible. Although the U-boat commanders’ orders permitted them to attack without warning, many of his colleagues chose to warn their victims when possible, and most of them probably would have done so in the case of a passenger liner. By his own admission, Schwieger torpedoed Lusitania before he had even identified her. The one point in Schwieger’s defense is that he certainly did not expect his target to go down in eighteen minutes. As in the case of Centurion the day before, Schwieger probably expected his first torpedo to stop Lusitania. Then, after those aboard had abandoned ship, he would sink his victim at leisure. But this is not what happened, and Lusitania‘s victims were not the only ones who paid a price. Winston Churchill, British first lord of the Admiralty when Lusitania went down, wrote in 1931:

The Germans never understood, and never will understand, the horror and indignation with which their opponents and the neutral world regarded their attack…. To seize even an enemy merchant ship at sea was an act which imposed strict obligations on the captor. To make a neutral ship a prize of war stirred whole histories of international law. But between taking a ship and sinking a ship was a gulf.

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Spring 1999 issue (Vol. 11, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Fateful Voyage of the Lusitania

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!