Throughout World War II, fighters, bombers and reconnaissance planes dominated headlines around the world. However, flying boats such as Germany’s Blohm und Voss Bv-138, Britain’s Short Sunderland, Japan’s Kawanishi H6K and H8K, and the U.S. Navy’s Consolidated PBY Catalina and Martin PBM Mariner earned a measure of fame in such vital roles as maritime reconnaissance, anti-submarine patrols and air-sea rescue, or “Dumbo,” missions. Although not as renowned or numerous as the PBY, the PBM was more advanced, more capable and—as even the most sentimental Catalina crewmen would have to admit—more comfortable to fly in than its predecessor.

Designed in 1936, just two years after the PBY, the PBM first flew in 1939 and entered production the following year. By May 1943, when the definitive PBM-5 model came out, it had distinguished itself in both the Atlantic and Pacific. Powered by two 2,100-hp Pratt & Whitney Double Wasp 18-cylinder radial engines, the PBM-5 had a maximum speed of 205 mph and a 3,275-mile range. In addition to APS-15 radar, it was armed with eight .50-caliber machine guns and 5,200 pounds of bombs or torpedoes. A total of 1,235 Mariners were built, compared to more than 4,000 Catalinas.

In the spring of 1945, Mariners saw some of their most active service in support of the invasion of Okinawa. Operating from Kerama Retto, a small island group south of Okinawa, they carried out anti-shipping operations against small enemy convoys and rescued the crews of Boeing B-29s lost while engaged in bombing Japan, as well as those of carrier planes downed in combat between Formosa and the Japanese Home Islands. One of several PBM-5 units based at Kerama Retto was Navy patrol bombing squadron VPB-27. In an interview with Aviation History senior editor Jon Guttman, Jack A. Christopher described his experiences as a Mariner crewman with that outfit.

Aviation History: Could you tell us something about your early years?

Christopher: I was born in St. Paul, Minn., on March 21, 1924, in a Salvation Army home. My mother had moved to Minneapolis after her husband left her. I went to school in Minneapolis, and then the war started.

AH: What influenced your decision to go into naval aviation?

Christopher: I’d lived near a naval air station in Minneapolis and went out there every weekend to watch them fly. In those days you could walk right onto the base and climb on the airplanes. So when I graduated from high school in January 1943—they let me out two weeks early to enlist—I wanted to be a pilot. I’d graduated 22nd out of a class of 247, and I passed all the tests until I took the colorblindness test—I couldn’t pass the blue-green test.

AH: How did you take that?

Christopher: I was devastated, as you’d expect to be when your dreams didn’t come true. I cried a lot. And I decided to wait until I was drafted.

AH: When did that happen?

Christopher: In May 1943 I got my draft letter, and I went out to Fort Snelling on June 1. At that time, if you passed your physicals with high marks, you could choose the Navy if you wanted. I decided that I’d rather be in the Navy than the Army. After going to boot camp at Farragut, Idaho, from June 12 to August 2, I could select a school, so I selected aviation ordnance. I figured that if I selected aviation, maybe I could get into planes. But then they claimed my blood pressure was too high and wrote “Rejected” on my slip. When they asked what I did, however, I said I had worked in the Twin City Gun Club for three to four years. Well, when I returned from leave, I found my name on the aviation ordnance list. Then they asked for volunteers for aerial gunner. I volunteered for that, and during my flight physical I passed the blue-green eye test—three times!

AH: What sort of training did you undergo?

Christopher: I went to the aviation ordnance school at Norman, Okla., from August 20 to December 4. I also had two weeks of radar training at Norman, from December 6 to 20. Then I went to gunnery school at Purcell, Okla., from December 22, 1943, to January 4, 1944. I scored in the top 10 percent of my ordnance class and was promoted to petty officer 3rd class right off the bat. I went through Norman and Oklahoma City in the winter with my peacoat over my arm, just to show off my rating. Third class petty officers were big stuff in those days.

AH: When did you first train in the PBM?

Christopher: From February 1 to April 11, I did operational training in PBMs. I remember when I first got to Banana River, Fla.—it seems you always got there at 2 or 3 in the morning—I went down to the ramp to look at our PBM-3Ss. The PBM-3S was an anti-submarine version. I was very disappointed—they didn’t have many guns on ’em, just a couple of .50-caliber machine guns in the nose, hanging by bungee cords, and one in the tail. At lunchtime one day, however, a guy came up to me and told me that two squadron PBMs were on the ramp. There they were—PBM-3Ds—big, beautiful birds with lots of guns. There was a ball turret in the nose with two .50s, a deck turret on top with another two .50s, a rear turret with two .50s and two .50s in the waist. I said, “That’s what I want to fly in.” I took the training and got my combat aircrew wings. We then had to fly some anti-sub patrols.

AH: What specific tasks were you trained in?

Christopher: As ordnance man, I was in charge of the guns, bombs, aerial mines and pyrotechnics. I also had to learn code, signal flag and semaphore to advance in rate. When we landed, I tied us up to the buoy and cast off. Because of that, when I was assigned to a regular plane, the crew painted a reference to me on the nose: “Our Buoy Chris.”

AH: When were you assigned to a squadron?

Christopher: From April 26 to May 1, I was awaiting my squadron assignment at Norfolk, Va., and after May 1, I was at Harvey Point, N.C. Sometimes we did shore patrol in Hertford, N.C., but most of the time was spent just cleaning barracks, doing maintenance on airplanes—hiding when we could. Then on June 1, 1944, VPB-27 was commissioned at Harvey Point. From August 4 to 23, we trained with aerial torpedoes off Key West, Fla.—the PBM-3D was designed to have torpedo racks. Finally, on September 28, we left Harvey Point for Jacksonville, Fla., and began to fly cross-country to Pensacola, then Eagle Mountain Lake, Texas, San Diego and Alameda, Calif. One plane from another squadron landed in the desert, but it wasn’t badly damaged. The crew jacked it up, stuck beaching gear under it and took off.

AH: Were those the PBMs you used in the Pacific?

Christopher: No, from Alameda they ferried them out to the Pacific to replace losses and left them there. I took more gunnery school, then we got our PBM-5s. A small crew—three or four crewmen—went back to get the new planes. The rest of us shipped out on November 25 aboard the escort carrier Attu, which was also ferrying North American P-51s out there. We got to Kaneohe, Oahu, on December 2 and trained in our new PBM-5s when they arrived. My usual plane was Bureau No. 59019, which we christened Dinah Might and decorated with a lady that one of the crew, Aviation Machinist’s Mate 3rd Class Sam Whitmore, designed on a tablecloth. We flew our first mission in Dinah Might on December 17—anti-sub practice with depth bombs and Fido, an acoustic torpedo that was top-secret at the time. Fido was used in conjunction with sonobuoys, tall cylinders with parachutes attached that we threw over the side. When each one hit the water, a microphone dropped down to listen for submarine propellers. We dropped them in pattern and listened for the sound. You knew which sonobuoy received the sound and dropped the Fido by that sonobuoy.

AH: Were there any problems during that phase of training?

Christopher: Unfortunately, we suffered our first fatalities during that period. On December 25 at 10:30 p.m., PBM-5 59017 was coming in for a night landing in heavy rain and poor visibility when it crashed in Kaneohe Bay. Six of the eight-man crew were killed. We held their funerals on January 6, 1945. Then on January 23, another PBM-5 crashed just outside of the bay. One engine went out, and the propeller wouldn’t feather. Due to the windmilling and vibration of the prop, they were forced down. They came in at about 120 knots, and upon hitting a swell, they flipped over and the plane exploded. Of the 13 who were flying, five of the crew were killed, plus three passengers from the maintenance group. Funeral services were held on February 6. Our crew flew over the scene of the crash and dropped flowers.

AH: How did you feel about seeing these squadron mates die like that, before you even reached the front?

Christopher: Maybe it was because I was so young, and I didn’t see them go down, and the squadron was so new. It didn’t affect me so much. I feel sadder when I hear of someone from the squadron dying now than I was then—the thought that we’re fading away.

AH: When did you finally get out to the front?

Christopher: On February 11, we took off for Johnson Island, then on to Kwajalein and Saipan, where we arrived on the 13th. From then until March 28, we operated from Saipan, performing patrols, Dumbos, et cetera. Between missions, we were stationed aboard the small seaplane tender Onslow, a destroyer escort–type ship.

AH: The seaplane tender served as your quarters between missions?

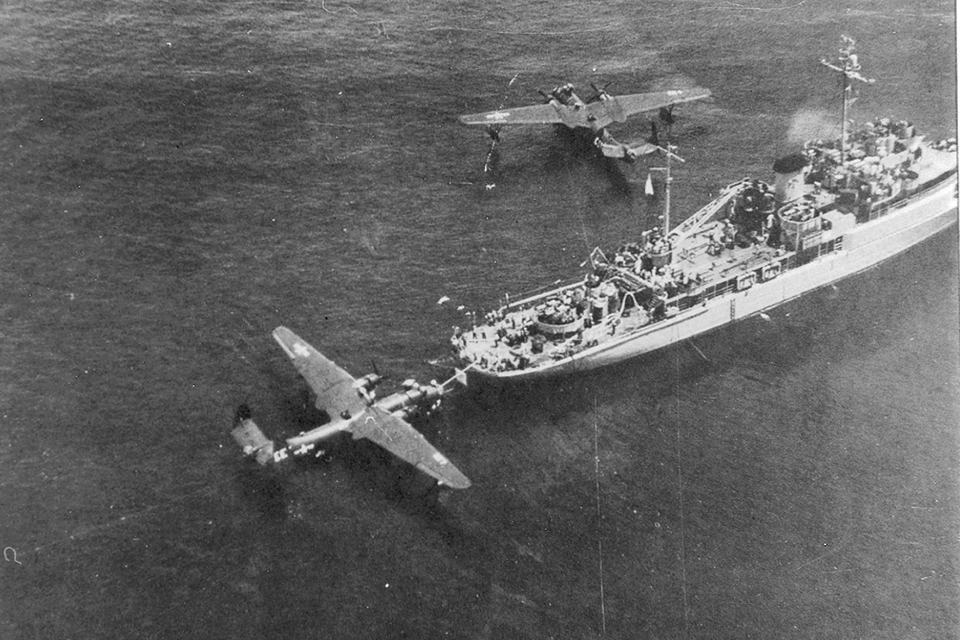

Christopher: Half the time. Half of the crew had to be on the plane all the time when on the water, so half of our life was spent living on the airplane. Each small seaplane tender held six flight crews, so there were three tenders per squadron. The others for VPB-27 were Yakutat and Shelikof. There were also a few big tenders at each base, for more extensive repairs or maintenance, which could hoist two PBMs on deck—at Kerama Retto, we had Norton Sound, Pine Island and the auxiliary tender St. George.

AH: What would comprise a typical PBM-5 crew?

Christopher: There were three pilots—one was the PPC [patrol plane commander], another acted as the navigator, and two pilots traded off on each patrol. There were two ordnance men, responsible for all the guns, the bow turret and the bombs; two radiomen to operate the radar and radio; and four machinist’s mates who served as plane captain, flight engineers and gunners. I was part of Crew 2, with Lieutenant Walter J. McGuire Jr. as Dinah Might’s PPC.

AH: What were living conditions like for crewmen doing a half-day shift aboard the PBM?

Christopher: It wasn’t bad. The plane had a galley and a bunkroom with four bunks. The head consisted of a can with a seat, a paper bag and a pee tube. At the base, we had to act like officers and enlisted men, but on the airplane we were just one family. The only other crews like that were PT-boat crews.

AH: Dumbos were rescue missions. How many people did you rescue?

Christopher: On March 4, we found eight survivors from a B-29 in two life rafts. Their plane had crashed while returning from a Tokyo raid. On March 10, we found a B-29 with some very high-ranking officers aboard who had wanted to go on a bombing run. The sea was too rough to land, so we dropped life rafts and smoke lights, and got in touch with a destroyer. The ship was too far away, so we circled over the rafts for six hours or so, even in the dark. We dropped them lights and stayed until they were rescued by that destroyer. They were so happy to be rescued that they invited us to a party on Tinian, but then the Battle of Okinawa started, so we couldn’t go. I always wanted to be a hero.

AH: The Allies took Kerama Retto, the small group south of Okinawa, before invading the main island. When did VPB-27 go out there?

Christopher: We arrived on March 29, the first squadron to land, and on April 1 we conducted our first anti-sub patrol around Okinawa. The Japanese submarines didn’t really attack, but they were around—just sitting out there. We had our first air raid that night. They had the aircrews man .50-caliber guns on the fantail of the seaplane tender. I was kind of scared, with all the tracers going up. But then a guy on a 5-inch gun mount yelled, “Riky tiky tiky tiky,” like it was a game, and I wasn’t scared anymore. The .50-caliber didn’t have any sights on it. I asked the ship’s ordnance man about that. He said, “You’ve heard of tracers, haven’t you?” Yeah, right. When the gun only holds 60 rounds.

AH: What were some of your operational activities at that time?

Christopher: I was an AOM2C, or aviation ordnance man, 2nd class. In addition to maintaining the guns, I was taught to be a bombardier when they formed the squadron. I operated the bomber’s panel and the intervalometer, which set the intervals for the bombs to drop. I had also trained on the Norden bombsight, riding on a big thing on four wheels, running along the floor, dropping plumb bobs on a target. Then I flew at 10,000 feet and dropped water-filled 100-pound bombs on the water. But I never used a bombsight in anger—all the bombing missions we flew were low level.

AH: Did you encounter enemy aircraft?

Christopher: Yes. The first time was during an anti-sub patrol on the night of April 12-13. They’d fly above us and drop flares. But we were also shot at by the Fifth Fleet.

AH: The Mariner, with its gull wings, was a pretty distinctive-looking airplane—and yet you came under attack from your own fleet?

Christopher: Yes. Our IFF [identification friend or foe] device went out a lot during rough landings. PBMs were called “Peter Baker Mike” on the radio, but our plane used to be called “Peter Bogey Mike” because our IFF would go out. Vought F4U Corsairs came up after us several times. We’d hear over the radio, “Scramble four chicks, bogey at such and such a position,” eventually followed by us saying, “Friendly coming in.” During another anti-sub patrol on the night of April 15-16, we dodged an unseen aircraft. Our radarman, Aviation Radioman 2nd Class John Derick, reported a plane coming on our tail. “I saw him on the radar,” he said, “I think it was more than one.” The pilot said, “Watch for him—if you see him, shoot him down.” He got closer, but just as we were about to shoot him, he turned off. He was an Eastern Aircraft FM-2 Wildcat, we think. The worst case of mistaken identity came on June 21, when PBM-5 No. 59026, piloted by Lt. j.g. J.B. Watsabaugh, was shot down by a Northrop P-61 Black Widow night fighter while patrolling the area around Okinawa. The plane caught fire in the forward bunkroom, and one engine was shot out. Aviation Machinist’s Mate 3rd Class Jeff Gwaltney was hit in the back. The plane made a crash landing at sea and sank. The 15-man crew escaped in life rafts, and after nine hours they were rescued by a Dumbo search plane from VPB-208.

AH: Your log mentions that you were flying another plane on an anti-sub patrol on April 20. Was yours undergoing repair?

Christopher: That was nice. We were taxiing around in the water and ran into a reef. We got old Dinah back for an anti-sub mission on the night of April 25-26.

AH: The next evening, April 27-28, you logged an attack on a Japanese convoy. What were the circumstances of that action?

Christopher: We had duty that day and were not supposed to fly—just do administrative work. I was glad to be on duty—I was sick as a dog, with a headache, nausea. I just wanted to lie around in my bunk all day. But then the squadron called to tell us that we had to get on the airplane. Our pilot had volunteered for a mission. When we saw them putting 500-pound bombs in our plane, we knew it was big. Our commander for this mission was Lieutenant McGuire, with Lieutenant Franz J. Eglies and Lt. j.g. Otho L. Edwards as the other two PPCs—there were three planes from VPB-27 and three from VPB-208. When we took off, I was so sick that I lay with my earphones on by my panel, with a bucket to throw up in. I didn’t say anything to anybody, though. Who wants to be left behind when your crew flies into danger?

AH: What was the mission?

Christopher: VPB-27 and VPB-208 attacked a Japanese transport convoy at the mouth of the Yangtze River. We encountered heavy flak. VPB-208 went in ahead of us, which woke the Japs up, so they were ready for us when we got there. I prayed to be well—and I was well, just like that. But a hit by a 5-inch shell cut our aileron cables, so we couldn’t bank. Our flight engineer, Aviation Chief Machinist’s Mate Julius J. Jaskot, was sitting on the back of his seat, with his feet up on the seat, to see what was going on, when a shell came in one side of the hull and out the other—where his legs would normally have been. It missed our gas line by just six inches. That same shell went through our propeller blades without striking them, as if it was synchronized—then it exploded. We must have been flying too low for the shell to arm.

AH: That’s four different disasters that one shell could have caused in a matter of seconds. Did you realize this at the time?

Christopher: No, I didn’t really think about it until we were going home. I just kept working all the gadgets that controlled the bombs, such as the intervalometer; I armed the bombs, made sure the bomb bay doors were open, ready for the pilot when he dropped them. The pilot dropped the bombs—we were too low to need a bombardier—and headquarters confirmed an 8,000-ton tanker sunk by us. Two other ships were also sunk.

AH: How did the pilots control the plane with the ailerons out of commission?

Christopher: They used the trim tabs. They were good when you were going fast, but not much good when you were slowing to land. We sweated out the landing very much. They just kept it straight and hoped it stayed that way as we got set for a crash. We got in OK, and the rearming boat came out and got us. They gave each of us a little bottle of brandy. I didn’t drink, so I gave mine to someone else. We also got a commendation: “The task group commander takes the greatest pleasure in offering an enthusiastic ‘well done’ to the pilots and crews of VPB-27 and VPB-208 who braved heavy enemy fire to strike at the well-defended Jap convoy last night. The admiration of all hands for the valor of the act is exceeded only by their gratitude for the safe return of all who participated….In their hands PBMs made history last night.”

AH: What happened to your PBM?

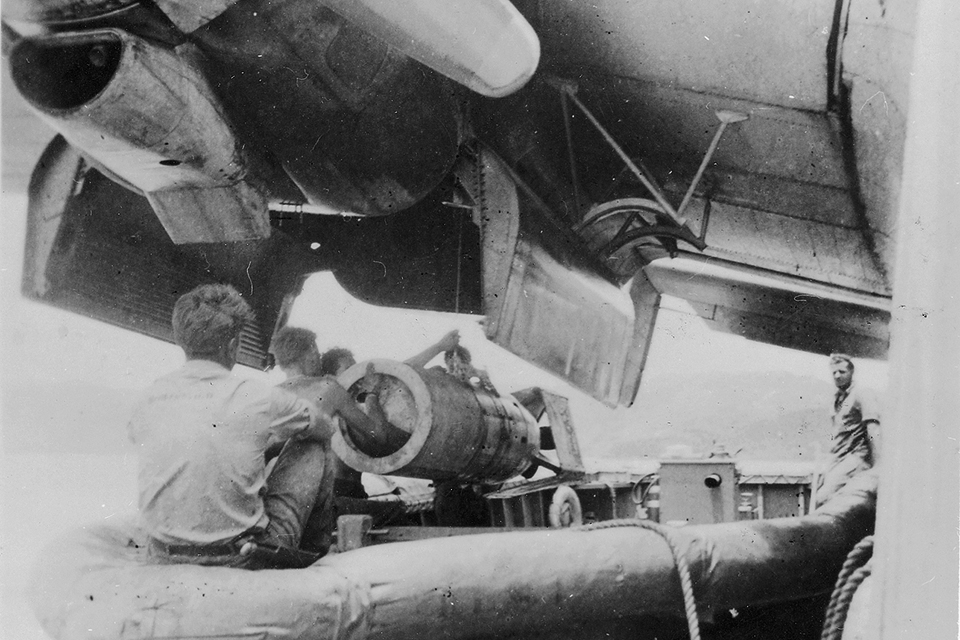

Christopher: There is a U.S. Navy official photograph of Dinah being hoisted aboard Pine Island for repairs—after our convoy strike that day.

AH: What were some other highlights of your activities after that?

Christopher: On May 1-2, we did another night anti-sub patrol, during which there were Japanese planes all around. On May 12, we were on another anti-shipping mission, looking for ships trying to hide in coves between China and Japan. We also searched for survivors of a VPB-21 PBM that had been shot down. They were not found by us, but they were found. During another night anti-sub patrol on May 13-14, Jap planes were seen on the radar, flying off our wing. On June 9, we flew a Dumbo, covering a strike by Republic P-47N Thunderbolts of the Seventh Air Force on Kyushu. Most of the time we flew alone, but this time we were escorted by two P-47s. Our job was to recover any pilots who had been shot down, but nobody was lost on that mission. On June 15, we provided a radar picket patrol. Since we had the best radar in the fleet—it covered 120 miles out—we were dispatched to cover certain sectors, so the Japanese fleet wouldn’t sneak up on our fleet.

AH: Did you use your torpedoes in any of your missions?

Christopher: That occurred at the end of June. On June 23, we came back from a night anti-sub patrol to learn that the Okinawa campaign had been officially declared over. On the 27th, our bombs were unloaded and two torpedoes installed. We were told to get out to the plane and PPC Walter McGuire, who was also VPB-27’s executive officer, would brief us. An Army “Duck” [DUKW amphibious personnel carrier] came by filled with soldiers. We both waved. The soldiers saw the torpedoes, and one hollered, “Give ’em hell!” I never felt so proud as at that moment. We were told that we, Crew 2, and Crew 7, piloted by Lieutenant Glen Welch, would attack a convoy composed of two destroyers with radar-controlled guns and 12 transports. We took off around noon and headed for the mouth of the Yangtze River. The convoy was located by radar. We attacked at about 240 feet at 160 to 170 knots. We encountered heavy anti-aircraft fire. Aviation Machinist’s Mate 2nd Class Bill Ferrall in the tail turret said that Lieutenant Welch’s plane was being followed by puffs of smoke, each one closer. The next one would have got him, but there was no “next one.” We dropped our torpedoes, except one of ours hung up. McGuire said, “We will make another run.” Being the first ordnance man, it was my job to see if we could release it. I crawled up into the wing with a screwdriver. We made a human chain, with Aviation Radioman 2nd Class Gene Cheak standing near the hole leading into the wing and Sam Whitmore with earphones on in the forward bunkroom. McGuire made the run and hollered “Drop” over the mike. Sam hit Cheak on the leg, Cheak hit me on the leg, and I jammed the screwdriver into the torpedo release. It dropped. McGuire made a fighter turn and took evasive action, and we got out of there. Because of the AA fire and poor visibility, we never actually saw if the torpedoes hit, but the runs were hot and appeared to be on target. We also attacked five “sugar dogs”—trawler-type ships—with our machine guns until the ammunition in our bow turret was exhausted. Both planes got back safely.

AH: Was weather ever a problem at Kerama?

Christopher: Whenever we took off on patrols, the decks of all the ships would be lined with people to see if we could get off despite the swells. During July 18-19, we flew from Okinawa to Saipan during an emergency typhoon watch.

AH: What were your last missions?

Christopher: During a search and anti-shipping mission on July 2, we strafed and bombed a lighthouse and radar station with 100-pound and thermite bombs in the face of light flak—our tail gunner was slightly wounded. Then, on July 4, we practiced a new torpedo plan, in which we would go into evasive action after dropping our torpedoes. On the 31st, we conducted a search while ready to perform Dumbo duty during an anti-shipping strike off the Shantung Peninsula. On August 6, we flew a search off the east coast of Japan. On the 7th, Crews 6 and 17, flying PBMs 59023 and 59150, went out on a night search for Japanese shipping around Formosa. No word was heard from them after they attacked two motor torpedo boats. Several squadrons searched for them, but no trace was ever found. By then, our squadron had moved to Buckner Bay on Okinawa. On August 15, we were on another search off the Shantung Peninsula. After we landed, I was on the airplane, listening to the radio, when the Japanese announced that they were surrendering. All the guns on the island were shooting for some time.

AH: How did you and Dinah’s crew react to the news?

Christopher: We threw our arms around each other and practically cried. Most of us prayed, thanking God for getting us through. AH: What became of your flying boat? Christopher: What we wanted to do was fly her back and fly under the Golden Gate Bridge, but it was not to be. On August 25, we ran on a reef as we were about to take off. We were barely able to save Dinah Might from sinking. Later they decided to junk her after her long combat hours—an unfitting end after such service.

AH: What did you do after the war?

Christopher: We were in occupied Japan, at Sasebo naval base, for about a month, from September 29 to November 6. From November 6 to 23, we took the transport ship Andromeda to Seattle, Wash. We got within sight of San Francisco when they switched to Seattle—which made us feel real good! From December 1 to 3, I traveled from Seattle to Minneapolis, and I got my discharge at Naval Air Station Minneapolis on December 6. On February 19, 1947, I reenlisted in the Naval Reserve in Minneapolis and served in attack squadron VA-66A, flying in Eastern Aircraft TBMs. I got out just before the Korean War started in 1950. I went back to work at Lamaur Inc., which produced shampoo, hairspray and perms, and worked with them for 44 years, retiring as production manager.

AH: Did you receive any medals for your activities in VPB-27?

Christopher: I got the Air Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross and Combat Aircrew Wings with three Gold Stars. I went from apprentice seaman to 1st class petty officer in two years.

AH: Any last comments on your service?

Christopher: Nobody ever heard of PBMs, but we flew by ourselves most of the time, hundreds of miles into Japanese territory. We were at the mercy of winds, currents and waves. We didn’t have nice, level runways to take off from and land on. There were no brakes, nose wheels or tail wheels, and we couldn’t walk away from our plane after flights. The PBM crews deserve to be remembered for their contribution to victory.

Senior editor Jon Guttman recommends for further reading: Mariner/Marlin, Anytime, Anywhere, by Turner Publishing Co.; PBM Mariner in Action, by Tom Doll; Seaplanes at War and Sailor Aviators, by Don Sweet and American Flying Boats and Amphibious Aircraft: An Illustrated History by E.R. Johnson.

Click here to read about modeling a PBM for your own seaplane collection!

This feature appeared in the May 2004 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!