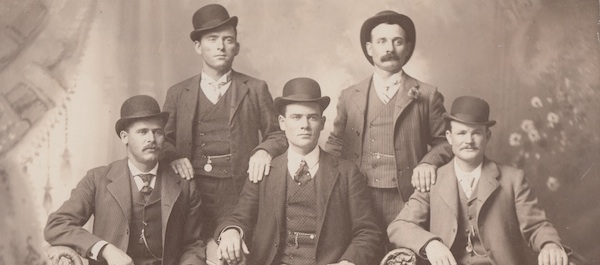

The Fort Worth Five. When these five members of the Wild Bunch had their photo taken in Fort Worth, it provided the Pinkerton Agents pursuing them with an invaluable tool. Left to right, Harry Alonzo Longabaugh (The Sundance Kid), William Carver (News Carver), Benjamin Kilpatrick (The Tall Texan), Harvey Logan (Kid Curry), and Robert Leroy Parker (Butch Cassidy). Photo courtesy Robert McCubbin.

If you are one of the millions who loves the 1969 movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, you owe it to yourself to watch the one-hour American Experience documentary, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Last Outlaws. It fills in a good bit of information and provides a deeper appreciation for what the movie got right historically within an entertainment medium. The gregarious Cassidy and taciturn Sundance of the 1969 film reflect the true personalities of the two, for example.

The American Experience documentary sets the scene effectively within the opening minutes. The story begins with the Wilcox Robbery, when Butch’s gang used too much dynamite and blew a safe in a railroad mail car into the middle of next week. That robbery is what made Butch famous, but as the narration points out, he and the outlaw gang he led, the Wild Bunch, was operating at the end of an era. The railroads had become determined to put an end to holdups, and the dogged pursuit that followed the Wilcox Robbery sent Butch and Sundance to South America and, ultimately, to their doom.

“Butch Cassidy” was the alias of Robert Parker. Raised by a fundamentalist Christian mother whom he loved deeply, he deflected dishonor from his family name after he became an outlaw, by creating a name based on that of Mike Cassidy, a small-time rustler who had been his mentor in crime.

The program says Butch was an unusual owlhoot, one who employed meticulous planning and understood one simple premise—he didn’t have to kill people to escape the law. It was not uncommon for holdup men to kill witnesses who could sound the alarm. Butch planned not only the job but the escape, leaving a series of fresh horses along the escape route so he and his cohorts would have fresh mounts while those of the posse pursuing them were becoming exhausted.

His reputation for pulling successful robberies spread among other outlaws and attracted them to him. One who found his way to Cassidy was Harry Longabaugh, a native of Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. Taking a job at age 14 on his cousin’s ranch in Colorado, Harry became a respected wandering cowboy, traveling from ranch to ranch to hire on. But the 1887 blizzard that brought as much as 100 feet of snow wiped out up to 90% of the livestock in some states, thereby wiping out the need for itinerant cowhands. Harry Longabaugh turned to crime, was sentenced to a year’s internment for stealing horses near Sundance, Wyoming, and left prison with the nickname The Sundance Kid. The Kid and Butch Cassidy met up when Butch was hiding out at Brown’s Park along the Outlaw Trail.

Newspapers across America picked up the story of the Wilcox Robbery, giving Butch and the Wild Bunch the notoriety of earlier outlaws like the James-Younger Gang or the Daltons. The railroad men had to put them out of business, and sought the services of the Pinkerton Detective Agency.

Newspapers across America picked up the story of the Wilcox Robbery, giving Butch and the Wild Bunch the notoriety of earlier outlaws like the James-Younger Gang or the Daltons. The railroad men had to put them out of business, and sought the services of the Pinkerton Detective Agency.

In the Pinkerton Agency, Butch was up against an organization that was as methodical in pursuing criminals as he was in planning crimes—and it had thousands of agents and informants across America. The agency was larger than the U.S. standing army of the time. And it did not give up.

When the Wild Bunch posed for a photo in Fort Worth, a Pinkerton Agent saw it in the photographer’s window, where it had been placed to advertise the cameraman’s work, and bought a copy. The agency distributed it far and wide, and the price on the heads of the men in the photo kept rising. The documentary covers “the rest of the story” on each of the men in the photograph.

There was a great deal of commerce between the U.S. and Argentina at the time, particularly in regards to cattle. Butch, Sundance and their companion, the mysterious Etta Place traveled to Argentina, bought 300 head of cattle and seem to have settled down, but the Pinkertons intercepted a letter Sundance wrote to his family in Pennsylvania, and circulated photos of the two outlaws throughout Argentina. What happened to Etta Place is unknown, but the two men fled into Bolivia and returned to the criminal life, leading to the first killing ever accurately attributed to Butch Cassidy. Their ultimate demise was not the romantic charge into dozens of guns depicted in the movie.

There is little to complain about in American Experience: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Last Outlaws. The period photos are interesting, including some of Butch, Sundance, Etta and their dog at their ranch in Argentina. Headlines from period newspapers capture a sense of the times and of the sensationalism employed to sell newspapers. Michael Murphy’s narration is effective; it is the sort of calm voice usually heard in documentaries, but he communicates a sense of urgency when necessary. The documentary’s various “talking heads” all have a good screen presence and provide useful and interesting information.

Highly recommended for fans of the Old West or for anyone who loved the Oscar-winning film and wants to know more about the real Butch and Sundance. The program has been airing on PBS stations and will likely be repeated; check your local PBS station for American Experience programs and airdates, or watch online at pbs.org. It is also available on DVD.

Like learning about the history of the Old West? Check out Wild West magazine!