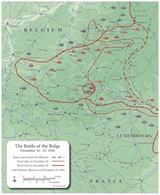

The Battle of the Bulge (December 16, 1944–January 16, 1945), also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the largest battle fought on the Western Front in Europe during World War II; it is also the largest battle ever fought by the United States Army. It was a German offensive intended to drive a wedge between the American and British armies in France and the Low Countries and recapture the port of Antwerp in The Netherlands to deny the Allies use of the port facilities. The German codename for the buildup to the offensive was Watch on the Rhine (Wacht am Rhine). The actual offensive was codenamed Operation Autumn Mist (Unternehmen Herbstnebel). It fell far short of its goals but managed to create a bulge in the American lines 50 miles wide and 70 miles deep, which gave the struggle its alliterative name.

The initial German attack force consisted of more than 200,000 men, around 1,000 tanks and assault guns (including the new 70-ton Tiger II tanks) and 1,900 artillery pieces, supported by 2,000 aircraft, the latter including some Messerschmitt Me 262 jets. In the opening phases of the battle, they would be facing only some 80,000 men, less than 250 pieces of armor and about 400 artillery guns. Many of the American troops were inexperienced; the German force included battle-hardened veterans of the tough fighting on the Eastern Front, but they, too, had green units filled with boys and with men who normally would have been considered too old for military service.

During the course of the month-long battle, some 500,000 German, 600,000 American and 55,000 British troops became involved. The Germans lost some 100,000 men killed, wounded and missing, 700 tanks and 1,600 aircraft, losses they could not replace. Allied losses—the majority of them incurred during the first week—included 90,000 men, 300 tanks and 300 aircraft, but they could make up these losses. In addition, an estimated 3,000 civilians died, some during the fighting and others executed by German combat and security forces. See “War Crimes in the Battle of the Bulge.”

The Ardennes Offensive was a massive gamble on the part of German dictator Adolf Hitler, one that he lost badly.

Battle Of the Bulge Facts

When was the Battle of the Bulge?

December 16, 1944 — January 25, 1945

Where was the Battle of the Bulge?

Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany

Who won the Battle of the Bulge?

Allied Victory

Troop Strength

80,000 Allies initially; ultimately 600,000+

200,000 Germany initially; ultimately 500,000

Casualties

90,000 Allies

100,000 German

Battle Of the Bulge Articles

Explore articles from the HistoryNet archives about Battle of The Bulge

» See all Battle of the Bulge Articles

Background to the Battle of the Bulge

By the winter of 1944, Nazi Germany’s situation was grim. Soviet forces were coming ever closer to the Fatherland from the east, and in the west Allied forces had crossed the German border. German Chancellor Adolf Hitler intended to launch a surprise attack in the west that would divide and demoralize the Western Allies and, perhaps, convince them to join Germany in its war against the communists of the Soviet Union. In May 1940, he had gambled on a surprise attack through the dense Ardennes Forest into Belgium and France and had won a stunning victory. Now he planned for history to repeat itself: once more German armor would advance through the concealing woods of the Ardennes to strike his enemies by surprise.

The German army commander in the West, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, thought the plan too ambitious. Other commanders also objected to taking resources away from the Eastern Front for this operation, but Hitler overruled them all.

Field Marshal Walther Model’s Army Group B would be responsible for the attack. His forces included Generaloberst Josef “Sepp” Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army, the largest and best equipped of the three striking armies, which was to drive northward, quickly cross the Meuse River and capture Amsterdam before the surprised Allies could regroup. Directly to the south of this force General der Panzertruppen Hosso-Eccard von Manteufel’s Fifth Panzer Army would push west in support of Dietrich’s attack. General der Panzertruppen Erich Brandenburger’s Seventh Army would protect the southern flank. The build-up was given the defensive-sounding codename Watch on the Rhine. Strict security measures included no radio communication to prevent Allied radio intercepts.

Field Marshal Walther Model’s Army Group B would be responsible for the attack. His forces included Generaloberst Josef “Sepp” Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army, the largest and best equipped of the three striking armies, which was to drive northward, quickly cross the Meuse River and capture Amsterdam before the surprised Allies could regroup. Directly to the south of this force General der Panzertruppen Hosso-Eccard von Manteufel’s Fifth Panzer Army would push west in support of Dietrich’s attack. General der Panzertruppen Erich Brandenburger’s Seventh Army would protect the southern flank. The build-up was given the defensive-sounding codename Watch on the Rhine. Strict security measures included no radio communication to prevent Allied radio intercepts.

On the opposite side, Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower was planning major operations in the northern and southern sectors of the front. Accordingly, the center, where the German attack was to fall, was the weakest part of the line. The American VIII Corps, under Major General Troy Middleton, consisted of the 4th, 28th, and 106th infantry divisions, most of the 9th Armored Division, and the two-squadron 14th Cavalry group. The 106th Infantry and 9th Armored were green units, untested in combat. The 4th and 28th had suffered high numbers of casualties during operations in the Hurtgen Forest and were receiving thousands of inexperienced replacements. This small, largely untried force had been assigned an 80-mile-long front; normally, a corps would be defending an area only about one-third that length.

Elsenborn Ridge and St. Vith

The German attack achieved the desired surprise but often encountered unexpectedly tough resistance. Their timetable did not allow for delays, but time and again the Americans slowed the enemy advance.

The road network in the Ardennes was narrow and rough. A key road for Sixth Panzer Army’s advance ran parallel to a stretch of high ground called Elsenborn Ridge. Along this ridge, ad-hoc groups of tanks, tank destroyers and dug-in infantry stubbornly resisted. General Eisenhower, immediately realizing his men were facing a major attack in the Ardennes rushed artillery to support the ridge. The firepower from their guns left the narrow roads choked with wrecked vehicles, in addition to those that broke down on their own from mechanical failure. After 10 days of intense fighting, Sixth Panzer Army abandoned its attempts to cross Elsenborn Ridge and sought other routes.

Many villages saw intense fighting. Because of the road situation, towns where several roads converged were critically important; one such town south of Elsenborn Ridge was St. Vith, Belgium. At St. Vith and nearby

towns, Fifth Panzer Army encountered stiff resistance; on the first day of the German offensive Eisenhower had ordered the 7th Armored Division to St. Vith to support 106th Infantry units. The narrow roads, ice, snow and mud prevented the Germans from massing their superior armor. The St. Vith pocket held until December 21 when, in danger of being encircled, the defenders withdrew. Their determined stand had thrown another monkey wrench into the German timetable. It bought time for the 82nd Airborne Division to set up strong defensive positions west of the town that blunted the enemy’s advance and temporarily pushed the attackers back across the Ambleve River. During the course of their engagements some units of the 82nd Airborne suffered over 80% casualties—the 509th Battalion reportedly took over 90% casualties—with most losses coming during the Allied counteroffensive that began in January.

Bastogne

To the west and south of St. Vith another crossroads town became the focus of intense fighting. When Eisenhower ordered the 7th Armored to St. Vith he also ordered the 10th Armored Division to Bastogne. It joined the 9th Armored, several artillery battalions, and infantrymen defending Bastogne and the small towns around it. On the 18th, the 705 Tank Destroyer Battalion arrived, and on the 19th the 101st Airborne. By the 20th the town was encircled by the advancing enemy, and on the 22nd, four Germans arrived with an ultimatum: surrender or heavy artillery will begin firing on the town. Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe sent them back to their commander with a one-word reply: “Nuts.” The artillery had already moved farther west, however, so the barrage was not forthcoming, though the Luftwaffe bombed the village by night.

On December 26, Bastogne’s defenders received a belated Christmas present: Lieutenant Charles P. Boggess with a few M4 Sherman tanks fought his way into Bastogne from the south. They were the lead element of a relief force from Lieutenant General George S. Patton‘s Third Army. When Patton struck with three divisions the following day, the German ring around Bastogne was broken.

End of the Battle of the Bulge

By this time, the Nazi offensive was running out of fuel, literally and figuratively. The Germans had waited for bad winter weather to launch their attack, to diminish the ability of Allied aircraft to support the ground troops. The weather also slowed the German advance, however, and this, the narrow roads and stubborn resistance wrecked their timetable. Improving weather conditions allowed Allied planes to take to the skies again and support the counterattacks that began pushing back the Germans. Despite a Luftwaffe offensive in Holland and a second major ground offensive the Germans launched in Alsace on January 1, the Third Reich could not regain the initiative. The Battle of the Bulge is officially considered to have ended January 16, exactly one month after it began, although fighting continued for some time beyond that date. By early February, the front lines had returned to their positions of December 16.