[dropcap]I[/dropcap]N 1970, I WAS in fifth grade. One day I gave an enthusiastic oral report on the Battle of Tarawa. When I finished, a fellow pupil raised his hand. “What are ‘Nips’?” my schoolmate asked.

“You know: Japs,” I replied. “Yellow bastards.”

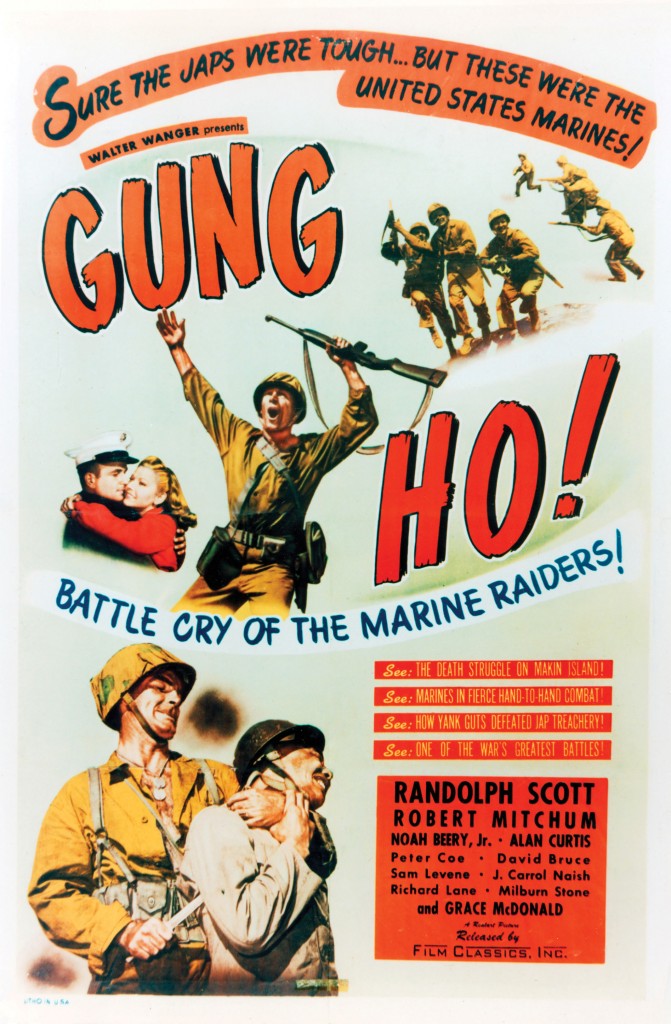

I had no idea that those terms were questionable. “Nips” and “Japs” were sprinkled liberally in the books I read about the war. “Yellow bastards” came straight out of LIFE’s Picture History of World War II. The images these phrases conjured came mostly from old movies I saw on television. Among these was Gung Ho!, a film I recall watching on “Sunrise Theater,” as WRAL-TV in Raleigh, North Carolina, called its Saturday morning movie broadcast.

Subtitled The Story of Carlson’s Makin Island Raiders, Gung Ho! tells the story of a raid on Japanese-held Makin Island in the Gilbert Islands chain on August 17-18, 1942, by two companies of Marines from the 2nd Raider Battalion, an outfit nicknamed “Carlson’s Raiders” after its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson. Two submarines ferried the Raiders to Makin on a hit-and-run operation meant to destroy installations, seize prisoners for interrogation, and divert attention from recent Marine landings on Guadalcanal. The Raiders rowed ashore in rubber boats, killed most of the garrison in fierce fighting, then withdrew to the two waiting subs.

Although largely forgotten today, at the time the Makin raid made breathless headlines. Late in 1942, one of the Raiders, Lieutenant W. S. Le François, chronicled the operation for the Saturday Evening Post. Hollywood producer William Wanger made this two-part account the basis for a major motion picture. The title comes from the motto of Carlson’s Raiders: “Gung Ho,” a Chinese phrase Carlson interpreted as meaning “Work Together.” Directed by Ray Enright, the film starred Randolph Scott as Colonel Thorwald, the fictionalized Carlson; the cast also included future star Robert Mitchum.

Gung Ho! premiered in December 1943, winning strong reviews and much praise for its realism. “As close to the real thing as you are likely to get,” said the Los Angeles Times. The portrayal of close combat was “hot and lurid,” reported the New York Times. “As a matter of fact, the stabbing and the sticking go on ad nauseam.”

Unremarked on in the reviews was the film’s portrayal of the Japanese, which audiences took to be as accurate as the battle sequences. In an early scene, a Marine officer questions each new candidate, asking, “Why did you volunteer for duty with this Raider battalion?”

“My brother died at Pearl Harbor,” says one. “They didn’t find enough of him to bury.”

Another man is a Filipino. “My sister was caught by the Japanese in Manila,” he bitterly replies. “We never heard a word from her, but we read in the newspapers what they did.”

Addressing his men for the first time, Colonel Thorwald tells them that the Japanese are formidable soldiers, but they have a weakness: “their inability to adapt themselves to new situations.” The Raiders can win by being able “to land where they think we cannot, to cross terrain which they think impassable.” In so doing, the Americans can handily defeat a force outnumbering them two-to-one. (The actual Marines at Makin outnumbered a small enemy garrison.)

The celluloid Raiders display ingenuity and imagination, most dramatically by painting a large American flag atop a key building and drawing Japanese troops toward the structure, which Japanese pilots bomb and strafe. (The flag ruse is fiction; Japanese pilots did attack Japanese defenders but by mistake, not because of American chicanery.)

The cinematic “Japs” are evil automatons. A machine gunner grins diabolically as he draws a bead on advancing Raiders. An infantryman brutally bayonets a helpless wounded Marine.

Imperial soldiers show smarts only in treachery. One, faking a wound, is about to shoot a Raider medic in the back when a badly injured Raider, sprawled on the ground, kills him by throwing a knife with amazing accuracy and force. A trio of “those monkeys,” as the narrator calls the foe, approaches two Marines, hands raised. “I think we ought to riddle them anyway,” says one American. “No, don’t kill ’em when they’re willing to surrender,” his buddy replies. “They know when they been licked.” The Japanese in the middle suddenly jacknifes, revealing a submachine gun strapped to his back that his comrades scramble to fire.

My point is not that the film’s depiction of Japanese soldiers was completely inaccurate. Atrocities did occur. In Gung Ho! all surviving Raiders make it to the waiting submarines, but in fact the enemy captured nine Marines and eventually beheaded them. However, together with other wartime movies, Gung Ho! cemented a collective American view of the Japanese as scarcely more than beasts, an assumption that excused American atrocities on the grounds that the “Japs” started it. When Time magazine reported approvingly in 1943 that American pilots had strafed Japanese in lifeboats, a reader protested in a letter to the editor, only to be disparaged by numerous other commenters. Would he feel remorse after “killing a helpless rattlesnake after he had spent his ‘strike’?” asked one. Another wrote of reading about the strafing incident with pleasure, adding that he would like to see a “Jap hide” nailed to every outhouse door in America.

As my 10-year-old self’s naiveté demonstrates, those and other stereotypes proved durable. They still enable many Americans to shrug off the firebombing of Japanese cities and avoid questioning the atomic immolations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By denying the enemy a human face, stereotypes make it easy to deny our own humanity.

Originally published in the March/April 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.