Information and Articles About Amelia Earhart, a famous woman in history

Amelia Earhart Facts

Born

July 24, 1897, Atchison, Kansas

Died

July 2, 1937, near Howland Island, Pacific Ocean

Spouse

George P. Putnam

Accomplishments

First woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean

Numerous aviation records

First woman to receive a National Geographic Society gold medal

First woman to receive a Distinguished Flying Cross

Charter member and first president of the 99s

Amelia Earhart summary: Amelia Earhart is one of the most prominent icons of the 20th century. She was a pioneering female pilot, determined and independent, and a supporter of women’s rights. Her numerous aviation firsts and her disappearance during an attempt to fly around the globe in 1937 have ensured her status as a legend.

Amelia Mary Earhart was born July 24, 1897, to Edwin and Amelia “Amy” (Otis) Earhart in her Otis grandparents’ house in Atchison, Kansas. Two years later, her sister Grace Muriel was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on December 29, 1899. Until Amelia was 12, the two sisters primarily lived with their Otis grandparents in Atchison —her grandfather was a successful judge—and attended a private school there. She spent summers with her parents in Kansas City.

In 1908, after their father, an attorney, got a job with Rock Island Railroad and moved to Des Moines, Iowa, Amelia and Muriel went there to live with their parents. It was in Des Moines that Amelia saw her first airplane at a state fair, although she was not impressed—it had only been six years since the Wright brothers made their first flight at Kittyhawk, North Carolina.

In 1911, Amelia’s grandmother Otis, her namesake, died. Around this time, her father began to drink heavily and eventually lost his job. In 1913, Edwin got a job in St. Paul, Minnesota, and the family moved. In the spring of 1914, Edwin took another job in Springfield, Missouri, but after moving, discovered that the man he was to replace had decided not to retire. Rather than return to Kansas with Edwin, where he eventually started his own law practice, Amy took her children to live with friends in Chicago’s tony Hyde Park neighborhood. Amelia’s shame and humiliation over her father’s alcoholism and from watching her mother struggle financially caused a lifelong dislike for alcohol and need for financial security.

Earhart graduated from Hyde Park School in 1915 and attended a finishing school in Philadelphia, the Ogontz School, the following year. Her ultimate goal was to attend Bryn Mawr, then Vassar. Over the Christmas break during her second year, 1917, she visited her sister in Toronto, Canada, where Muriel was attending St. Margaret’s College. Earhart encountered many World War I veterans and, although she was already helping with the war effort at Ogontz as secretary of the Red Cross chapter, she wanted to do more. She left Ogontz to volunteer as a nurse in at Spadina Military Hospital, where many of her patients were French and English pilots. She and Muriel spent time at a local airfield watching the Royal Flying Corps train.

During the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919, which swept through Toronto in the summer of 1918, Earhart contracted a severe sinus infection that required surgery and a lengthy recovery period. That fall, she went to live with her mother and sister in Northampton, Massachusetts, where her sister was preparing to attend Smith College. During her convalescence, she learned to play the banjo and completed a course in automobile maintenance.

In the fall of 1919, Earhart enrolled in a pre-medical program at Columbia University in New York City. Although she did well academically, she left after a year to rejoin her reconciled parents in Los Angeles, California, having changed her mind about becoming a doctor and hoping to help her reconciled parents stay together.

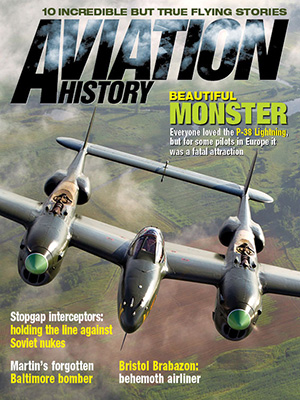

Read More in Aviation History Magazine

Read More in Aviation History Magazine

Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

In Los Angeles, Earhart saw her first airshow and took her first plane ride—”As soon as we left the ground, I knew I had to fly.” She began taking lessons at Bert Kinner’s airfield on Long Beach Boulevard from Neta Snook on January 3, 1921. Snook gave her lessons in a rebuilt Canuk, the Canadian version of the Curtiss JN4 Jenny, which proved to be to lumbering and slow for Earhart—by summer, she had a bright yellow Kinner Airstar that she called The Canary. To help pay for the plan and flying lessons, she worked in a photography studio and as a filing clerk at the Los Angeles Telephone Company.

Snook thought Earhart was ready to fly solo after 20 hours of flight training—generally 10 hours were deemed sufficient at the time—but Earhart insisted on having stunt training before flying alone. She began participating in public aerial demonstrations and air rodeos. In the fall of 1922, she set an unofficial altitude record for women, flying to 14,000 feet. On March 17, 1923, she received top billing for the air rodeo and opening event at Glendale Airport in Glendale, California.

Unfortunately, due to a change in the Earhart family’s fortune and her own inability to earn enough to keep the plane, Earhart sold the Airstar in June 1923. In 1924, her parents divorced and Earhart moved back to the East Coast with her mother and sister, and eventually to Boston, Massachusetts where she worked at Denison House teaching English to immigrant families. She became a full-time, live-in staff member at Denison House, which provided social services and education to the urban poor by having educated women and poor people live together in the same residence.

In 1928, she was invited to join pilot Wilmer “Bill” Stultz and co-pilot/mechanic Louis E. “Slim” Gordon as a passenger on their transatlantic flight set to take place a little over a year after Charles Lindbergh’s landmark flight—she would be the first woman to fly across the Atlantic. On June 17, 1928, they left Newfoundland in a Fokker F7 and, about 21 hours later, arrived at Burry Port, Wales. The successful flight made headlines across the world—in no small part because book publisher and publicist George P. Putnam was involved in the project. He would become Earhart’s manager and eventually her husband. A ticker-tape parade in New York City and a reception at the White House by President Calvin Coolidge catapulted the crew to fame. Although Earhart was just a passenger—in her own words, “a sack of potatoes”—the trip set the stage for Earhart to become a pioneer of aviation and a celebrity. By the end of the year, Putnam had arranged for her first book to be published, titled 20 Hrs. 40 Min., Our Flight in the Friendship: The American Girl, First Across the Atlantic by Air, Tells Her Story.

In August 1929, the Cleveland Air Race, a transcontinental race, was opened to women as a nine-stage race that began in Santa Monica, California, and ended in Cleveland, Ohio. In the Women’s Air Derby, dubbed the “Powder Puff Derby” by humorist Will Rogers, Earhart piloted a new Lockheed Vega-1, the heaviest of the planes flown in her class. Due to several mishaps and one fatality, only 16 of the 20 pilots completed the race. Louise Thaden won the Class D race with a Beechcraft Travel Air Speedwing, Gladys O’Donnell came in second with a Waco ATO, and Earhart came in third in her Vega, two hours behind the winner.

Never had so many female pilots spent a significant amount of time together or gotten to know each other so well. Because of the camaraderie and support they felt during the race, Thaden, O’Donnell, Earhart, Ruth Nichols, Blanche Noyes, and Phoebe Omlie gathered to discuss forming an organization for female pilots. All 117 of the women pilots licensed at the time were invited to join. On November 2, 1929, twenty-six women, including Earhart, met at Curtiss Airport in Valley Stream, New York to form the organization now known as the 99s, named for the 99 charter members. Earhart was the first president of the organization.

Following Putnam’s divorce in 1929, his professional relationship and friendship with Earhart developed into more. After numerous proposals, Earhart finally accepted and they were married on February 7, 1931. Earhart called the marriage a “partnership” with “dual control.” Putnam continued to manage Earhart’s career, arranging her flying engagements, which were often followed by lecture tours to maximize the opportunity for publicity.

On April 8, 1931, Earhart set an altitude record in a Pitcairn autogiro—a type of early helicopter—that would stand for years. She was sponsored by Beech-Nut company in an attempt to be the first pilot to fly an autogiro from coast to coast, but discovered on arrival that another pilot had accomplished the feat a week before. She decided to attempt to be the first to complete the first transcontinental round-trip flight in an autogiro, but crashed after taking off at Abilene, Texas, on the return leg of the trip, for which she received a reprimand for negligence from Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aviation Clarence Young. Although she completed the trip in a new autogiro, she abandoned the rotorcraft after several other mishaps.

To dispel rumors that Earhart was not a skilled pilot but merely a publicity figure created by Putnam, they began planning a solo transatlantic flight from Harbor Grace, Newfoundland, to Paris, which would make her the first female and second person to fly solo across the Atlantic. Earhart took off May 20, 1932, in her Lockheed DL-1—five years to the day after Lindbergh began his historic flight. Mechanical problems and adverse weather forced Earhart to land in a pasture near Londonderry, Ireland, rather than Paris, but her achievement was undeniable. The National Geographic Society awarded her a gold medal, presented by President Herbert Hoover, and Congress award her a Distinguished Flying Cross—both awarded to a woman for the first time.

Earhart continued to set records and achieve firsts for females in aviation. In August 1932, she became the first woman to fly nonstop coast-to-coast across the continental United States in her Lockheed Vega. She had the fastest nonstop transcontinental flight by a woman in 1932. In 1933, she was one of two women to enter the Bendix race from Cleveland, Ohio, to Los Angeles, California, which officials had opened to women, allowing them to compete against men in the same race for the first time. Although she crossed the finish line six hours behind the men, on her return flight, she beat the nonstop transcontinental flight record she set the previous year by two hours.

Earhart received many awards and accolades for her record-setting achievements. She won the Harmon Trophy as America’s Outstanding Airwoman for 1932, 1933, and 1934. She was given honorary membership in the National Aeronautic Association and was awarded the Cross of Knight of the Legion of Honor by the French government.

Earhart launched a fashion line in 1934 but did not have success and closed it by the end of the year. She also worked with Paul Mantz, a Hollywood stunt pilot and technical advisor, to prepare for a new record flight from Hawaii to California as the first person to fly solo across the Pacific. She received FCC approval to install a two-way radio in her Hi-Speed Special 5C Lockheed Vega—the first in a civilian aircraft.

On December 3, 1934, another pilot and his two-man crew had disappeared attempting to complete the flight from California to Hawaii. In spite of the disappearance and public opinion that the flight was both dangerous and pointless, the Vega was shipped to Honolulu, Hawaii, in late December and on January 11, 1935, Earhart took off from Wheeler Army Airfield near Honolulu. A little over 18 hours later, she landed in Oakland, California, after an uneventful flight.

Hoping to break another record, in April 1935 she became the first person to fly solo from Los Angeles, California, to Mexico by official invitation from the Mexican Government, but became lost 60 miles from her ultimate goal of Mexico City and had to stop for directions. In May, she set a record traveling nonstop from Mexico City to Newark, New Jersey, arriving in just over 14 hours. In August 1935, she flew in the Bendix race again, this time with Mantz, and placed fifth, winning $500.

Earhart joined the Purdue University staff as a women’s career counselor and advisor in aeronautics in 1935 after being invited by university president Edward C. Elliott to lecture at the university in 1934. In December 1935, Purdue had a conference on Women’s Work and Opportunities—Earhart was the featured speaker.

In July 1936, Purdue and other sponsors helped Earhart purchase a Lockheed Electra 10E, which she called her “flying laboratory,” and she began planning a trip to fly around the world at the equator. In early 1937, she and Frank Noonan, her navigator, began their first attempt. They flew from Oakland, California to Honolulu, Hawaii, March 17–18, but crashed while attempting take-off from Luke Field near Pearl Harbor on March 20. After the plane was repaired at the Lockheed plant in California, they began a second attempt, this time traveling from west to east, departing from Miami, Florida June 1.

On July 1, having completed 22,000 miles of the trip, they took off from Lae, Papua New Guinea for Howland Island in the central Pacific. After about 18 hours of flight, they lost radio contact with the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Itasca, which was helping guide them in to land on the island. They were never seen or heard from again. President Roosevelt authorized a massive naval, air, and land search, but nothing was found and it was ended on July 18. Putnam financed his own search for his wife but was also forced to call off the search in October 1937. On January 5, 1939, Earhart was declared legally dead in a Los Angeles, California, Superior Court.

The mystery of Earhart and Noonan’s disappearance continues to fuel speculation and searches—it is one of the greatest mysteries of the 20th century. Amelia Earhart continues to live on in our collective imagination for her accomplishments and because of the mystery of her disappearance. There are countless biographies and four movies about her life, not to mention numerous books, movies, and television shows about her disappearance and what may have happened to her and Noonan.

Articles Featuring Amelia Earhart From HistoryNet Magazines

Featured Article

The Life Of Amelia Earhart

A tomboy who defied early-20th-century conventions, Earhart successfully crusaded for women pilots’ place in the sky.

They called Amelia Earhart “Lady Lindy” after her first flight across the Atlantic. She was tall and slim, with short, wind-swept hair, and looked so remarkably like Charles Lindbergh that she could have been his sister. Although she disappeared flying the Pacific in 1937, her name is still frequently in the news, thanks mostly to “aviation archaeologists” who believe they know the circumstances of her demise and where her plane and other evidence can be found.

Amelia Mary Earhart was born in Atchison, Kansas, on July 24, 1897. She referred to herself simply as “AE,” and that’s what her friends called her. Earhart was considered a tomboy because she dared to do things that girls at the turn of the century usually did not do—she climbed trees, “belly-slammed” her sled in the snow to start it downhill, and hunted rats with a .22 rifle. Later she attended a girls school in Pennsylvania and became a nurse’s aide in a Toronto hospital, helping to care for wounded soldiers during World War I.

At the time Earhart was growing up, women were beginning to assert their right to enter careers traditionally reserved for men. She kept a scrapbook of newspaper clippings that highlighted women entering occupations in motion-picture directing, law, advertising, management and automobile mechanics.

Her introduction to aviation came on Christmas Day 1920, when her father, a lawyer, took her to the official opening of a new airfield in Long Beach, California. She had her first airplane ride three days later with barnstormer Frank M. Hawks. “As soon as we left the ground,” she later said, “I knew I myself had to fly.”

Earhart took her first flying lesson on January 3, 1921, from Neta Snook, one of the first women to graduate from the Glenn Curtiss school. The flight cost $1 per minute, which Earhart paid for in World War I Liberty bonds. The airplane was a dual-control Canuck, the Canadian version of the famous World War I Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny.”

In July 1921, Earhart bought a rebuilt Kinner Airster for $2,000. The Kinner was an unstable, two-seat biplane powered by a 3-cylinder, 60-hp Lawrence L-2 engine. The airplane was painted yellow, and Earhart promptly named it The Canary.

There is no denying that Earhart had difficulty learning to fly. It took her more than 15 hours of flight time and nearly a year to solo the Kinner, and she had a number of mishaps afterward, most of them during landings. As one biographer noted: “Unfortunately, though highly intelligent, a quick learner, and possessed of great enthusiasm, Amelia did not, it seems, possess natural ability as a pilot. This is no disparagement of Amelia, it is simply the view of many of her contemporaries in the flying world. Indeed, given this apparently important drawback, it is to her great credit that she was subsequently able to achieve so much.”

One aspect of Earhart’s personality proved dominant—perseverance. She was obsessed with flying and built up solo flying time in The Canary when she could afford it. She set a women’s altitude record in October 1922 by coaxing the Airster to 14,000 feet. The record was broken by Ruth Nichols a few weeks later, but the effort had put Earhart in the news.

In 1925, Earhart moved with her mother and sister to Massachusetts. She attended college, became a social worker in Boston, and taught English to immigrants. But the lure of flying remained strong. When she was financially able, Earhart invested a small sum in a local airport. She was soon back in the cockpit, where she attracted much press attention by promoting flying, especially for women.

Earhart’s life changed abruptly in April 1928, when she was invited to be the first woman to fly across the Atlantic. It was primarily a publicity effort instigated by George P. Putnam, a book publisher with a flair for finding and promoting profitable book projects. One of Putnam’s coups was Charles Lindbergh’s book We, which became a best seller after it was published in July 1927.

Some say Putnam planned to publish a book, titled “She,” about the first woman to make a trans-Atlantic flight. He was looking for “the right sort of girl”—a well-educated and physically attractive pilot. After he ruled out other women pilots, including Ruth Elder and Ruth Nichols, he chose Earhart and promptly labeled her “Lady Lindy.” Putnam would make Earhart a national heroine.

For the flight, a Fokker F7 was purchased secretly from Commander Richard E. Byrd by Mrs. Frederick E. Guest. Originally from Great Britain, Guest named the plane Friendship to represent the close ties between England and the United States. Although Earhart was said to be in command of the flight, she was actually only a passenger. Wilmer “Bill” Stutz would be the pilot, and Louis E. “Slim” Gordon would serve as the co-pilot and flight mechanic. While the details of the flight were being worked out, Earhart and Putnam became friends, but she remained leery of his promotional schemes.

Test flights were made by Bernt Balchen and Floyd Bennett, who were employed by Fokker. Friendship’s wheels were then exchanged for pontoons, and the plane was flown to Newfoundland. After a series of delays, Earhart, Stutz and Gordon left Trepassey Harbour just before noon on June 17, 1928. They flew through harsh weather, including snow squalls, but 20 hours 40 minutes later—with only 25 gallons of fuel left—Friendship was guided to a landing by an Imperial Airways Sea Eagle at Burry Port, Wales. On their return, the three were greeted with a ticker-tape parade in New York and receptions in Boston, Chicago and Medford, Mass. Earhart was also given a reception at the White House by President Calvin Coolidge.

Earhart wrote a book about the flight, which she named 20 Hrs. 40 Min., went on an exhausting lecture tour in the winter of 1928-29, and became an associate editor of Cosmopolitan magazine. Her articles on aviation subjects were well-received, and she became a spokesperson for women in aviation. In July 1929, she became assistant to the general traffic manager of Transcontinental Air Transport (later to become TWA).

Earhart made her first attempt at competitive flying during the first Santa Monicato Cleveland Women’s Air Derby. The event, later named the “Powder Puff Derby” by comedian Will Rogers, took place in August 1929 as the opening feature of the National Air Races. Earhart flew a Lockheed Vega and placed third, behind Louise Thaden and Gladys O’Donnell.

Shortly after the race, 26 licensed women pilots met informally at Curtiss Field on Long Island and formed a group that was incorporated the following year as the Ninety Nines. In their constitution, they proposed “to assist women in aeronautical research, air racing events, acquisition of aerial experience, administration of aid through aerial means in times of emergency arising from fire, famine, flood, or war.” Earhart was elected the first president. Their stated aim was “to provide closer relationship among pilots and to unite them in any movement that may be for their benefit and for that of aviation in general….”

Earhart continued her writing, but she also flew to many locations where she spoke publicly about women’s flying. She became an official in the National Aeronautic Association and encouraged the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) to establish separate world altitude, speed and endurance records for women.

As soon as those records were established, Earhart got her name into the record books. She established women’s world speed records for 100 kilometers with no load, then with a payload of 500 kilograms, on June 25, 1930. Ten days later, she set a women’s world speed record of 181.18 mph over a 3-kilometer course.

Setting records was one way to keep aviation in the news, but Earhart also wanted to promote aircraft as a safe means of transportation. She helped organize a new airline in September 1930–the New York, Philadelphia and Washington Airways–and served as vice president for public relations.

Earhart’s relationship with George Putnam was becoming more serious. Ten years her senior, Putnam basked in the publicity he had brought the young flier. When he divorced his wife of 18 years, Earhart reluctantly agreed to marry him after agonizing over the decision. The wedding was held February 7, 1931. She later described their marriage as “a reasonable partnership…conducted under a satisfactory system of dual control.”

By the time Earhart was married, there were about 300 licensed women pilots in the United States, and many of them were competing for the fame that records brought. Among them were Bobbi Trout, Laura Ingalls, Elinor Smith and Ruth Nichols. Competitive by nature, Amelia needed something to keep her name in the news. Her husband ordered an autogiro for her a week after their marriage, but she did not wait for her own machine to be delivered to make another record-setting attempt. She set an altitude record for men and women of 18,415 feet on April 8, 1931, in an autogiro borrowed from the Pitcairn-Cierva Autogiro Co.

Earhart canceled her order for an autogiro when the Beech-Nut Co. offered its autogiro for a transcontinental flight; she flew it to the West Coast in nine days. She had an accident at Abilene on the return trip when, as she put it, “the air just went out from under me.” The autogiro hit two cars and damaged the craft’s rotor and propeller, but Earhart was unhurt. It was replaced by another autogiro, and she continued her trip east. However, she was issued a formal reprimand for “carelessness and poor judgment” after the accident from the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce. She made two more trips that year and had a minor crack-up in Detroit.

One January morning in 1932, Earhart put down the newspaper she had been reading and asked her husband, “Would you mind if I flew the Atlantic—alone?” He agreed, and the two of them secretly began to make preparations for her to use a Lockheed Vega she had bought in 1929. Bernt Balchen, who had piloted Commander Byrd across the Atlantic in 1927, agreed to rebuild and test the Vega, which she had damaged at Norfolk in 1930.

Balchen and Eddie Gorski, a skilled mechanic, installed a 420-gallon gas tank in the fuselage, a new engine and new instruments, including a drift indicator, two compasses and a directional gyro. Balchen taught Earhart to fly using instruments and then quietly checked her out in the renovated Vega. The weather was improving over the Atlantic, and Balchen flew Earhart to Harbour Grace, Newfoundland. She took off for Paris on the afternoon of May 20, 1932—the fifth anniversary of Lindbergh’s Atlantic flight. Fourteen hours 54 minutes later, after being driven off course by strong north winds and overcompensating for southward drift, she landed in a pasture near Londonderry in Northern Ireland. It had been a fatiguing flight through storms and icing conditions with a leaky gas line and a burned-out exhaust pipe. Lindbergh had been honored with far more awards and receptions after his trans-Atlantic crossing than he had anticipated. Now the same thing was happening to Earhart. She was besieged by reporters and photographers as she traveled to London, France, Belgium and Italy to be decorated. Back home, at a National Geographic Society dinner in her honor, she received the society’s gold medal from President Herbert Hoover. Congress voted Earhart the Distinguished Flying Cross; she was the first woman to be so honored. It was presented to her by Vice President Charles Curtis for “displaying heroic courage and skill as a navigator at the risk of her life.” In writing about the flight, Earhart said she had made it to prove that “women can do most things that a man can do.” Not everything, she added, but certainly “jobs requiring intelligence, coordination, speed, coolness, and will power.”

Next, Earhart planned another record-setting flight in the Vega. On August 24 and 25, 1932, she set a women’s nonstop transcontinental speed record, flying 2,447.8 miles from Los Angeles to Newark in 19 hours 5 minutes. The following year on July 7 and 8, she broke her own record by making the flight in 17 hours 7 minutes 30 seconds, winning the Harmon Trophy.

Earhart began preparations in 1934 to compete for a $10,000 prize offered by Hawaiian pineapple and sugar growers, hotel owners and businessmen to publicize the islands by flying from the Territory of Hawaii to the States. She acquired an updated Lockheed Vega with the latest instrumentation, two-way radio and controllable-pitch propeller. Earhart and the plane were taken by ship to Hawaii, where she ran into a storm of media criticism for planning to make the flight purely as a publicity stunt. One newspaper report was subheaded “Nothing To Be Gained, Much May be Lost, Say Aviation Experts.”

Ignoring the criticism, Earhart made a lecture tour of the islands and then left Honolulu on January 11, 1935, for Oakland, California. She followed a course drawn up by Captain Clarence Williams, a Navy navigator, and arrived without difficulty 17 hours 7 minutes later. She was the first person to fly the 2,408-mile distance alone. It was also the first flight in which a civilian aircraft carried a two-way radio.

As before, Earhart was feted and received congratulations from many prominent admirers. President Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote her a long letter, remarking, “You have scored again…[and] shown even the ‘doubting Thomases’ that aviation is a science which cannot be limited to men only.”

It had been rumored before the Hawaii-California flight that Earhart was planning to fly around the world, but other newsworthy flights were to come first. She became the first person to fly solo from Los Angeles to Mexico City on April 19 and 20, 1935, completing the trip in 13 hours 23 minutes. On May 8, she followed that with a solo flight from Mexico City to Newark in 14 hours 19 minutes.

Earhart’s fame and her continuing struggle to give women the opportunity to fly resulted in her appointment as a consultant in careers for women at Purdue University. The university trustees established a $50,000 fund for aeronautical research to encourage the study of aeronautics.

Two members of the Purdue Research Foundation donated a total of $40,000 for Earhart to buy a twin-engine Lockheed 10E Electra to be used as a “flying laboratory,” equipped with Bendix instruments, a Sperry autopilot and a radio compass. Earhart wanted to use the specially equipped craft to study navigation problems in addition to what she termed “the human reactions of flying.”

One of the interesting friendships Earhart developed at that time was with Eleanor Roosevelt. She was planning to teach Eleanor to fly, and the First Lady actually got a student permit. Mrs. Roosevelt never pursued the matter, but the two corresponded frequently.

Read More in Aviation History Magazine

Read More in Aviation History Magazine

Earhart continued to work on plans for a world eastwest flight. She planned to fly from San Francisco via Hawaii, Australia and India, across Africa to Brazil and on to New York. The longest and most difficult leg would be the long haul over the Pacific. At first, an in-flight refueling by a Navy PBY-1 over Midway Island was considered. Midway was used by Pan American Airways as a flying boat base, and there was no airstrip on the island. That idea was abandoned when Earhart learned that the Department of Commerce was establishing a weather observation station on tiny Howland Island, described as “nothing more than a sandbar,” that would include a small landing strip. Planning then centered on using Howland for refueling. George Putnam became heavily involved in bringing the project together. He made most of the planning decisions and contacts with Navy, Treasury and Commerce officials.

The flight began from Oakland on March 17, 1937, with Frederick Noonan and Captain Harry Manning, an experienced ship captain, serving as navigators, and Paul Mantz, a movie stunt pilot, acting as co-pilot. Mantz was to go along as far as Honolulu, Noonan would continue on to Howland, and Manning would stay with the flight until they reached Darwin, Australia. Earhart would fly the rest of the trip alone. Noonan, a competent navigator with a reputation for excessive drinking, had been on the Pan American pioneering runs across the Pacific. Manning was captain of USS President Roosevelt and had agreed to take a six-month leave of absence from his ship to participate in Earhart’s flight.

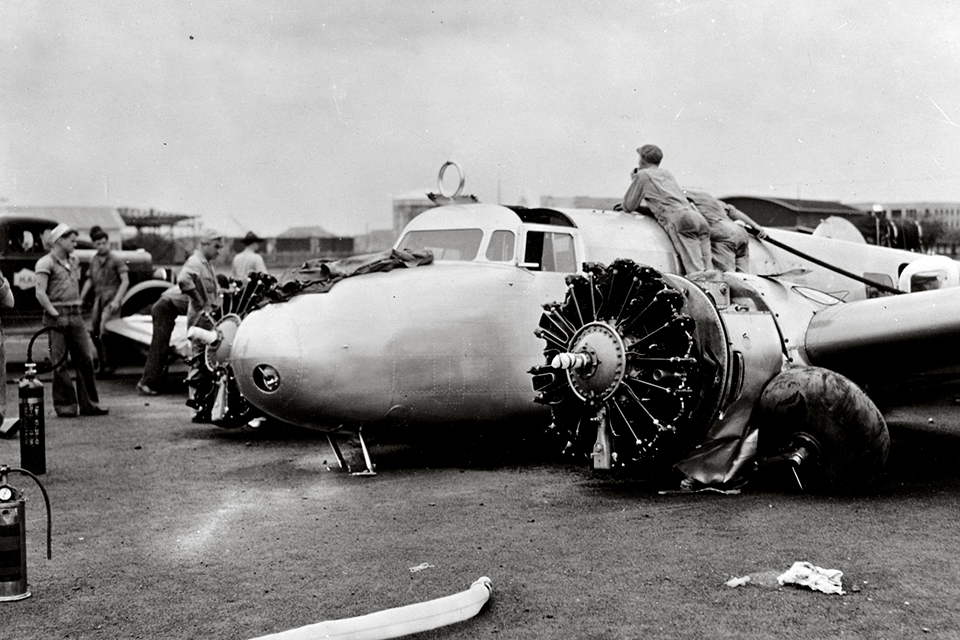

The 15-hour 47-minute flight to Hawaii was uneventful, and a new eastwest record between the two points was established. After a delay for weather, Earhart lined up the heavily loaded Lockheed on the runway of Luke Field (later known as Ford Island) to take off for the 1,900-mile leg to Howland. There was a crosswind as she pushed the throttles forward and gained speed. Slowly, the right wing dipped, and Earhart compensated by pulling back on the left throttle. The plane then veered to the left in a classic ground loop. Sparks flew under the airplane as it dropped to its belly.

Luckily, there was no fire and no one was hurt. But the plane had to be repaired before it could fly again, and it was shipped back to Lockheed in California. Earhart believed a tire had blown during the takeoff attempt, but that was never proved. Mantz later said that Earhart had a tendency to hold a twin-engine plane straight on takeoff solely with throttles, rather than using the rudder. In Mantz’s experience, this technique would almost always produce a ground loop.

Earhart was upset by the accident but determined to make another try. She received generous checks from well-wishers, including the Lockheed mechanics who repaired the Electra. Meanwhile, she changed her plans and decided to fly a reverse route, from west to east. Captain Manning’s leave was up, but Noonan agreed to be her navigator for the entire trip.

The newly rebuilt plane was ready to go in May, and a test flight was made from California to Miami with several stops. Earhart and Noonan departed for San Juan, Puerto Rico, on June 1, 1937, and proceeded from there to Venezuela, to Brazil, and across the Atlantic to Africa. En route she ignored Noonan’s calculations in favor of her instincts. They landed at Senegal, 163 miles north of Dakar, their intended destination. They flew to Dakar, had the engines checked and then made the long, hot journey across Africa with stops at Gao, Fort-Lamy, El Fasher, Khartoum and Massawa. Noonan found navigation difficult because the few maps available were often inaccurate.

They continued to Eritrea and then nonstop to Karachi, an aviation “first”—no one had previously flown from the Red Sea to India. They reached Calcutta on June 17, having made 15 stops thus far. The aircraft had performed well, and there had been no major problems.

The next legs were to Rangoon, Bangkok, Singapore, Bandoeng and Soerbaja, Java. At that point, Earhart was having problems with the fuel analyzer and electrical instruments, and she decided to return to Bandoeng for repairs. She had a bout with dysentery, the cause of which she thought “must be the petrol fumes.” After weather delays and sightseeing, they flew on to Port Darwin, Australia, via Koepang, Indonesia. They reached Lae, New Guinea, on June 29, 1937, after a 1,200-mile flight in 73Ž4 hours.

The engines were thoroughly checked, the spark plugs cleaned, and a fuel pump and the autopilot repaired. Everything not needed for the transpacific flight, including parachutes and some survival equipment, was packed to be sent home. Earhart cabled the last of several articles to the New York Herald Tribune. She then met with senior government officials and took care of details such as fumigation of the plane, a check of immunization certificates, and customs clearance.

Noonan had trouble getting his chronometers accurately set because time signals, necessary for accurate navigation, could not be picked up by radio. There are reports that Noonan and Earhart were exhausted at that point and that Noonan got drunk, causing a delay in their takeoff for Howland, 2,227 nautical miles from Lae. Meanwhile, the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Itasca was waiting off Howland to act as a radio contact. The Navy had a weather officer and two mechanics waiting on the island with a run-in cylinder assembly, new spark plugs, oil, gas and food. A seaplane tender, USS Swan, was approximately 200 miles northeast of the island to monitor the HowlandHawaii leg. Other ships—USS Ontario and USS Myrtlebank—were positioned along the intended flight track between the Nukumanu Islands and Howland.

Earhart and Noonan had on board about 1,100 gallons of 87 octane fuel, plus 50 gallons of 100 octane for extra takeoff power. That would allow them to stay airborne between 20 and 21 hours, enough for a cruising range of approximately 2,460 nautical miles. Noonan estimated they would reach Howland in about 18-and-a-half hours.

The weather was reported favorable on July 2, 1937, although the flight would run into rain showers and overcast skies. That meant that Noonan probably would not be able to make star shots for celestial navigation. They took off from the 3,000-foot dirt strip at 12:30 p.m., in the heat of the day. The plane used every inch of the strip and disappeared briefly below a 20-foot drop off a cliff at the end. A commercial pilot reported that he saw the plane’s props throwing spray before it climbed slowly northeastward to about 100 feet and flew out of sight.

There has been much speculation about what happened in the hours that followed. Itasca made radio contact with the plane, but static interfered with transmissions. Earhart sent one clear message: “Overcast…will listen on hour and half hour on 3105 [kilocycles].” Chief radioman Leo G. Bellarts asked for her position and estimated time of arrival at Howland, then gave her weather details. When Earhart failed to report at the next scheduled time, Bellarts transmitted weather information by voice and Morse code. Earhart’s voice was heard briefly on the radio several times as dawn neared. She asked for a bearing to the ship.

Read More in Aviation History Magazine

Read More in Aviation History Magazine

At this point controversy enters the scenario. Bellarts received one message and reported it in his log as follows: “KHAQQ cling [calling] Itasca we must be on you but cannot see U but gas is running low been unable reach you by radio we are flying at altitude 1000 feet.” Another radio operator on the ship logged the report in the third person, as follows: “Earhart on NW [now] sez running out of gas only 1/2 hour left cant hr us at all/we hear her and are sending on 3105 es 500 same time constantly and listening in for her frequently.”

There was a radio direction finder on Howland, but the operator was never able to get a fix on the plane because the Electra’s transmissions were too brief. The plane had been in the air for 19 hours by that time. Suddenly, a clear voice message from Earhart was heard: “We are circling but cannot hear you. Go ahead on 7,500 now or on schedule time on half hour.”

Bellarts sent out the letter “A” continually on 7,500 kilocycles and told her to “Go ahead on 3105.” She did so immediately—the first time during the flight there had been two-way contact. Everyone on the Itasca relaxed as her message came in clearly: “KHAQQ calling Itasca. We received your signals but unable to get a minimum. Please take bearing on us and answer on 3105 with voice.”

For an hour, some signals were received from the plane at the same strength, indicating that the plane was probably circling the ship’s position. Meanwhile, Itasca had started making black smoke, which trailed the ship by about 10 miles. The log of messages received by the ship showed that Amelia did not respond to questions put to her and gave no position reports during that time. However, she did report “200 miles out,” then “100 miles out, coming up (fast).” At 1912 Greenwich time, she reported “one-half hour fuel and no landfall.” Sixteen minutes later, she reported circling. The last message ever received was a plaintive one: “KHAQQ to Itasca. We are on line of position 157-337. Will repeat this message on 6210 kilocycles. We are running north and south.” All attempts to make further contact by Itasca’s radio operator were fruitless.

The consensus by those who have studied the flight is that Amelia had to ditch the Lockheed. If she put the gear down and landed too fast, the plane may have nose-dived into the sea. That could have prevented the pair from getting out of the aircraft with the life raft and survival equipment. If she made a relatively soft ditching with empty fuel tanks, the two might have had time to get out before the plane sank.

The Navy and Coast Guard went all out to locate the pair, but no trace was ever found. Writers came up with all kinds of scenarios to explain their disappearance, but none have been proved valid so far. Captain Elgen Long, an airline pilot who set his own record of flying around the world at the four corners of the globe, believes the plane can be found about 35 miles west-northwest of Howland. But a search for it using an undersea vehicle in an area 20 miles by 40 miles would be an expensive undertaking.

Various “conspiracy” theories about the tragedy have circulated for years. It has been suggested that the pair were seen on one of the Marshall Islands, that they were captured and tortured by the Japanese because they were on a spying mission for the United States, or that the plane somehow survived and was later destroyed by the U.S. Army for mysterious reasons.

Read More in Aviation History MagazineThere have been reports from island natives that the two white Americans were buried on various Pacific islands during World War II. Saipan islanders have reported seeing a white woman wearing what appeared to be man’s clothing, accompanied by a tall man. None of these reports have been substantiated.

Read More in Aviation History MagazineThere have been reports from island natives that the two white Americans were buried on various Pacific islands during World War II. Saipan islanders have reported seeing a white woman wearing what appeared to be man’s clothing, accompanied by a tall man. None of these reports have been substantiated.

One theory that persists because of zealous publicity is that of Richard Gillespie, head of The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR). He believes that the Electra came down off Nikumaroro, an uninhabited atoll in the Republic of Kiribati, a Central Pacific island nation. Gillespie has made three trips there and found a piece of aluminum, the heel of a shoe and a piece of Plexiglass. He says that these findings substantiate his thesis that the plane lies underwater nearby. He had the aluminum tested in December 1996 at Pittsburgh’s Alcoa laboratories, but the tests were inconclusive.

Like several other aviation mysteries, this one may never be solved. But it seems there will always be someone who tries. Verifiable scientific proof is needed. It has been 60 years since the disappearance of one of the world’s most famous pilots. Still, there are those who believe proof will yet be forthcoming.

The late C.V. Glines was an award-winning aviation writer. For further reading: The Sound of Wings, by Mary S. Lovell; Amelia Earhart, by Doris L. Rich; and Amelia, My Courageous Sister, by Muriel Earhart Morrissey and Carol L. Osborne.

This feature originally appeared in the July 1997 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!