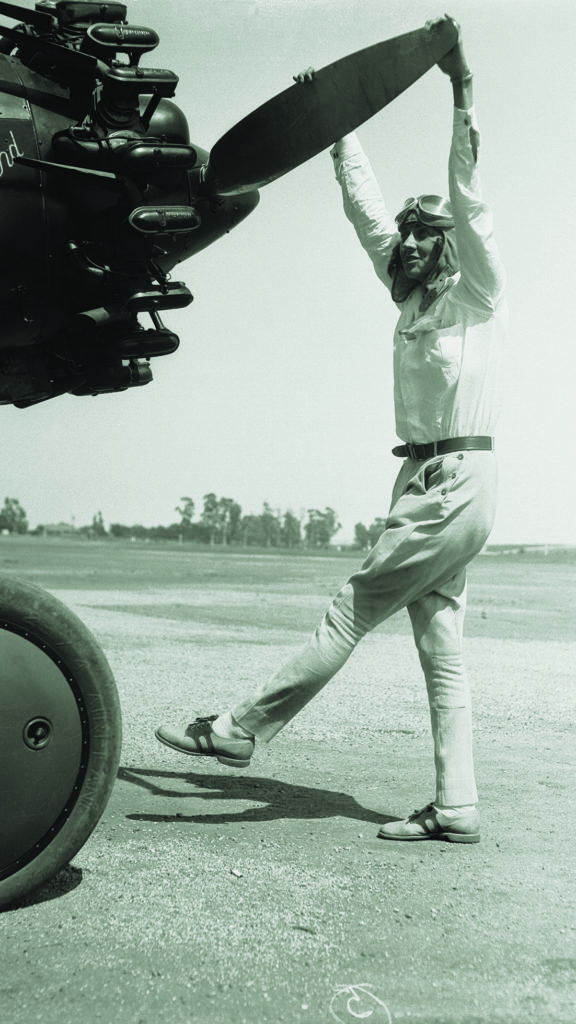

IN THE 1920s, when civilian aviation was organizing itself and aviators were setting benchmark upon benchmark, air races were a popular spectator sport. The All Women’s Air Derby, as it was known officially, drew crowds to see and meet record setters, nonconformists, and all bands between. At the extremes flew unassuming Amelia Earhart, a demure daredevil from Atchison, Kansas, and bohemian Florence “Pancho” Barnes, a Union Army balloonist’s granddaughter who declared, “Flying makes me feel like a sex maniac in a whorehouse with a stack of $20 bills.” Endurance flier Evelyn “Bobbi” Trout was known for flying by night—and living to tell the tale. Ruth Elder financed flying lessons with her beauty contest winnings. Feminist Opal Kunz’s husband, George, was chief mineralogist at Tiffany’s and well able to keep her in planes. Blanche Noyes flew for the air mail service. Stylish Alabamian Ruth Elder had failed in 1927 to become the first woman to fly from Long Island to Paris, France (she was forced to ditch in the Atlantic), but the attempt had earned her dinner at the White House and a Manhattan ticker tape parade. These and fellow competitors—pint-size Vera Dawn Walker, banker’s daughter Neva Paris, test pilot’s wife Claire Mae Fahy, and more—took off from Clover Field—now Santa Monica, California, Municipal Airport—on August 19, 1929, aiming to log the fewest air hours reaching Cleveland, Ohio. That nine-day journey killed one racer, made the survivors famous, and signaled American women’s full-fledged entry into aviation.

Between its early 1900s inception and the decade following the Great War, aviation evolved dramatically. Aircraft went from dual-winged contraptions of wood, fabric, and wire puddle-jumping along at 80 mph and landing in whichever farm field presented itself to sleek metal monoplanes able to exceed 200 mph and travel great distances. The airborne future looked limitless. To seduce passengers away from railroads, airlines needed larger, faster, and safer aircraft but also terminals at which to take on and disperse travelers and their luggage. Dearborn, Michigan’s Ford Airport was the first such facility to offer comfortable waiting and boarding areas, though it was not unusual for passengers to get a face full of propwashed grit. Grass airfields hung on into the 1930s.

The airplane industry echoed the automobile’s introduction, with scores of manufacturers opening, closing, merging, and acquiring one another. Unlike car makers with their assembly lines, the aircraft industry emphasized craftsmanship, often hand-building planes one by one from the wheels up. Also unlike the auto industry, which was concentrated around Detroit, Michigan, the aircraft industry had no geographic hub. Headquarters and factories dotted the map: Bell and Curtiss Wright in Buffalo, New York; Republic and Grumman on Long Island; Boeing in the Northwest and later Wichita, Kansas. Los Angeles, California, was home to Douglas, Lockheed, Northrop, North America and Vultee.

Charles Lindbergh’s heroic 1927 trans-Atlantic solo flight legitimized flying as a skill, a source of celebrity, and a business proposition, attracting millions in investment and stoking public interest in flying as a means of travel and in fliers as a new category of star.

In 1929, 9,098 men held flying licenses in the United States. So did 117 women. Those among the latter trying to make a living at flying had few permanent career options. Many had to resort to air circuses—traveling carnival-style troupes of aviators setting up for business for a few days in the hinterland to entertain crowds with wing-walking and trick flying, as aviatrix Phoebe Omlie and husband Vernon did for a living—and barnstorming in the air from town to town, sometimes solo, to spin up deals to get paid for aerial stunts. The film industry offered opportunities as a stunt woman or stand-in. Wealthy women took up flying for the challenge and the notoriety. On June 24, 1929, Opal Kunz made Page 1 of The New York Times for crashing her newly purchased cream and gold Travel Air C-9827 biplane at Morris Plains, New Jersey, with an ex-sailor aboard. Kunz promptly bought another Travel Air, which she had christened “Betsy Ross” by Mrs. Thomas Edison at Newark Metropolitan Airport. Wellesley-educated stockbroker’s daughter Ruth Nicols took flying lessons on the sly. Evelyn Trout began flying at 17 with money earned at the family filling station in Southern California. Emulating star dancer Irene Castle, Trout cropped and pomaded her black hair, dressed mannishly and went by “Bobbi”—“She looks like a boy but flies like a man,” a reporter wrote. Inspired by Lindbergh, Ruth Elder, 23, learned to fly. Hollywood picked her for lead roles in the 1928 Paramount vehicle Moran of the Marines (Paramount 1928) and Universal’s 1929 The Winged Horseman.

Women had long been making news in the air, pushing back against a patriarchal aviation culture. Harriet Quimby flew the English Channel in 1912, three years after Louis Blériot was the first man to achieve the feat. In 1921, former wing-walker Phoebe Omlie broke the world parachute jump record. In 1921, Louise Thaden flew to 20,260 feet, a record for a female aviator. On June 18, 1928, Amelia Earhart, accompanying two male pilots, flew the Atlantic in a Fokker trimotor, just a year after Charles Lindbergh’s famous New York-Paris solo flight. Global certifying body FAI—the France-based Fédération Aéronautique Internationale—derisorily classified these achievements as “miscellaneous air performance.” In the same vein, air race organizers, all male, refused to let women compete. That barrier stood until 1929, when in collaboration with promoter Cliff Henderson, who during World War I had flown with the 101st Aero Squadron, the National Exchange Club, a businessmen’s group, announced the All Women’s Air Derby. Adhering to the mainstream model, the 2,700-mile route between Santa Monica, California, and Cleveland, Ohio, involved multiple days, many stops, and much ballyhoo (see map, p. 49). To have a shot at the $25,000 first prize, a prospect needed FAI and National Aeronautics Association pilot’s licenses and 100 hours of solo flight, including 25 hours of soloing cross-country. She also had to be a certified airplane mechanic. The race drew 70 applicants; of 40 qualifiers, 20 entered, including German aerobat Thea Rasche, “The Flying Fraulein,” and petite Australian Jessie Maude “Chubbie” Miller, first woman to pilot a plane from England to Australia.

Racers’ rides varied widely in engine displacement, prompting the sponsor to divide the field: fliers whose aircrafts’ engines displaced 510 cubic inches or less were lightweights, anything with a bigger bore was a heavyweight. The dominant model was an open-cockpit biplane, with a 510- or 800-cubic-inch engine, built by Travel Air since 1925 in Wichita, Kansas, which billed itself as the Air Capital of the World. Travel Air executive Walter Beech, who thought having female aviators race would sell airplanes, had helped bring about the event.

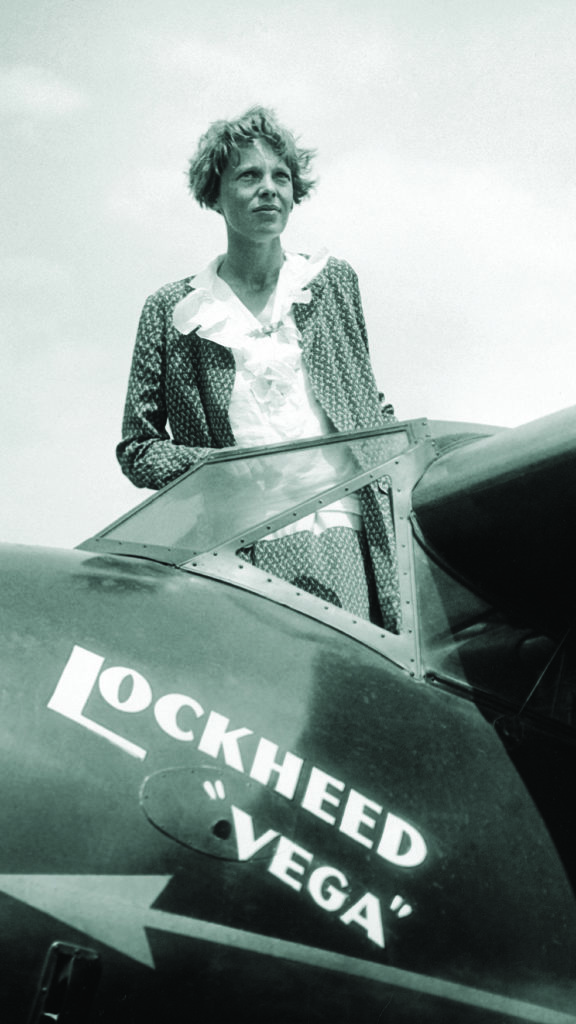

At noon on August 18, 1929, Santa Monica’s seaside morning fog was burning off and Clover Field was buzzing. Humorist and aviation enthusiast Will Rogers, with flier and sidekick Wiley Post, was there to cover the race for his Gulf Oil radio show. Seeing the competitors primping for the press, Rogers, coining a catchphrase, cracked, “Looks like a powder puff derby to me.” Earhart, who had flown into Santa Monica in her shiny red heavyweight five-passenger Lockheed Vega, was favored to win. Officials decided the 300-hp Travel Air Opal Kunz had just bought was too much aircraft for a woman; she rented a 200-hp Travel Air. Edith Folz fired up the Kinner 5 engine in her Alexander Eaglerock Bullet, a stylistic standout with its retractable gear, underslung wing, and enclosed cabin; Folz, a clotheshorse, had a custom lavender flying suit she called a “Folzup,” tailored for flying and ground-bound casual wear.

Earhart, Thaden, and Marvel Crosson were worried that Mary Haizlip, 19, who had learned to fly from her World War I aviator husband Jimmy, was missing. Word came that a plane had gone down in a nearby field—the women recognized it as stunt pilot Phoebe Omlie’s Monocoupe. Omlie, who had lost her way in the fog, was about to be jailed for smuggling dope when Earhart intervened; the sheriff’s deputy let the other woman off. Pancho Barnes arrived in jodhpurs and beret, smoking her usual cigar.

Among the 3,000 spectators was Edgar Rice Burroughs, author of the Tarzan series. Another celebrity, tool fortune heir Howard Hughes, shyly wished Crosson good luck; himself an aviator, Hughes was sponsoring 4’11” Vera Dawn Walker in a Curtiss Robin. To reach the rudder pedals, Walker had to prop herself forward with pillows. Until Hughes intervened, she had been stuck for a sponsor.

he San Bernardino leg took the aviators 68 miles east—once they were able to get going. Mishaps abounded. Earhart had to turn back to unstick her aircraft’s jammed starter. Mechanical trouble delayed Haizlip by a day; she arrived aboard a replacement craft. Besides staying aloft, the challenge was keeping on course without radios, using questionable charts to reach ill-marked landing fields. Savvy fliers like Barnes kept an eye peeled for railroad tracks, a reliable guide. Barnes was first to San Bernardino, where 4,000 spectators crowded the airport.

The second day’s leg was 348 miles to Calexico, California, and Yuma and Phoenix, Arizona. Earhart’s propeller broke; a spare had to be flown in from Los Angeles. Trout’s 100-hp Golden Eagle Chief cartwheeled across a field, requiring days of repair work. Airport mechanics accidentally contaminated the fuel tank of Elder’s Swallow biplane with five gallons of oil. Landing hard amid dust clouds, Kunz damaged her Travel Air’s landing gear. When Fahy, who had been having trouble maintaining control, set her Travel Air down at Calexico, she found snapped aileron wires that appeared to have been sabotaged with acid.

The flyers next headed to Phoenix, Arizona, 150 miles northeast of San Bernardino.

Barnes, following the wrong rails, veered far off course, landing in a farmer’s field in Mexico. “I wheeled around, goosed the throttle, and got outta there,” she recalled.

Desert temperatures and a stifling cabin made Elder woozy. Losing her map to the slipstream, she landed her red Swallow NC8730 in a field of grazing bulls. A rancher’s wife appeared, shouting that she was scaring the herd. Elder about-faced and took off.

At dusk that day in Phoenix all pilots were accounted for except Warsaw, Indiana-born Marvel Crosson, 29, who with younger brother Joe was a bush pilot in Alaska. A month before, Crosson had gained fame reaching 23,996 feet in a Travel Air Jet J-5. Searchers found her corpse in the Gila River Valley, her parachute unopened, several hundred feet from the wrecked Chaparral. Decades later the son of the Travel Air factory investigator who worked the case said his late father had suspected carbon monoxide poisoning in Crosson’s death, which dominated the next morning’s front pages. Exhaust also had sickened other competitors. Race officials suggested canceling. Survivors said they would push on to honor their fallen sister.

The stops were as much work as the flying, if not more. Each destination tried to set a record for hospitality. Mayors and city councils overscheduled the aviators with charity appearances, photo sessions, and soirees. Even the most media-savvy among the competitors had not reckoned with the kind of notoriety that would draw 10,000 spectators, many of them rabid autograph hounds, to an airfield outside Wichita, Kansas.

Required to keep a gallon of water and three days’ worth of rations aboard, the fliers had little stowage, and at events often appeared clad in wrinkled frocks and sporting windburned cheeks, V-shaped tans, and goggle-induced owl eyes. Some wore plus-fours under their skirts to keep from flashing too much thigh negotiating cockpits. By Day 4, racers were recovering from Marvel Crosson’s death. In honor of her wrong-way turn, Barnes painted “Mexico or Bust!” in white on her Travel Air’s fuselage.

At Pecos, Texas, gawking drivers pulled onto the airstrip as competitors were landing. Colliding with a car, Barnes totaled her plane, knocking her out of the race. Accidents and illnesses continued. Margaret Perry, diagnosed with typhoid fever, had to enter the hospital in Abilene, Texas. Fouled oil lines grounded Haizlip. On high, Noyes noticed her luggage smoldering. She set down in the desert and pulled up her plane’s wooden flooring to extinguish the flames with sand.

On August 26, 1929, 15 of the original 20 landed at Cleveland, Ohio, Municipal Airport. Thaden came in first in the heavy class, with O’Donnell second and Earhart third. Omlie, Folz, and Keith-Miller led the light brigade. “To us, the successful completion of the Derby was of more importance than life or death,” said Thaden. “The public was skeptical of airplanes and air travel. We women of the Derby were out to prove that flying was safe; to sell aviation to the layman.”

After a round of congratulatory effusions that included autographing one another’s cloth flying helmets, the racers gathered beneath a Cleveland airport grandstand to talk

business, specifically, about forming an organization; in time they and other women fliers, a total of 99 founding members, signed up. That November, 26 women fliers met at Curtiss Airport on Long Island. Mechanics were revving a Challenger’s engine; as they sipped tea served from a toolbox on wheels, the women had to raise their voices, nearly shouting as they discussed jobs, locating an office for their group, and assembling files on female fliers. Membership would be open to any woman with a pilot’s license. The topic of a name came up. The Climbing Vines, Petticoat Pilots, Homing Pigeons, and Gadflies were among the suggestions. “The Ninety-Nines,” said Earhart, referring to the charter members. The phrase stuck; the group elected Earhart president and Thaden treasurer and vice-president.

The Derby reprised in 1930 but soon the male-dominated air establishment was reverting to form. Florence Klingensmith’s death at the 1933 Frank Phillips Trophy Races in Chicago—metal stress felled her overpowered Gee Bee Model Y Senior Sportster—led organizers to bar women from the 1934 finals. In 1935 pressure from female fliers got that ban lifted. Thaden and copilot Noyes took first place in the prestigious 1936 Bendix Race in a Beechcraft C-17R. The irrepressible Barnes did stunt flying on Howard Hughes’s 1930 film Hell’s Angels and founded the first stunt pilots union. In the 1930 Powder Puff Derby, she broke Earhart’s record for speed by a woman flier, reaching 196.19 mph in a Travel Air Type R Mystery Ship. Earhart, who in 1931 married publisher George P. Putnam, flew relentlessly, soloing across the Atlantic in 1932. On a 1937 attempt to circumnavigate the globe with navigator Fred Noonan, Earhart vanished, a mystery beloved of curiosity seekers and conspiracy theorists.

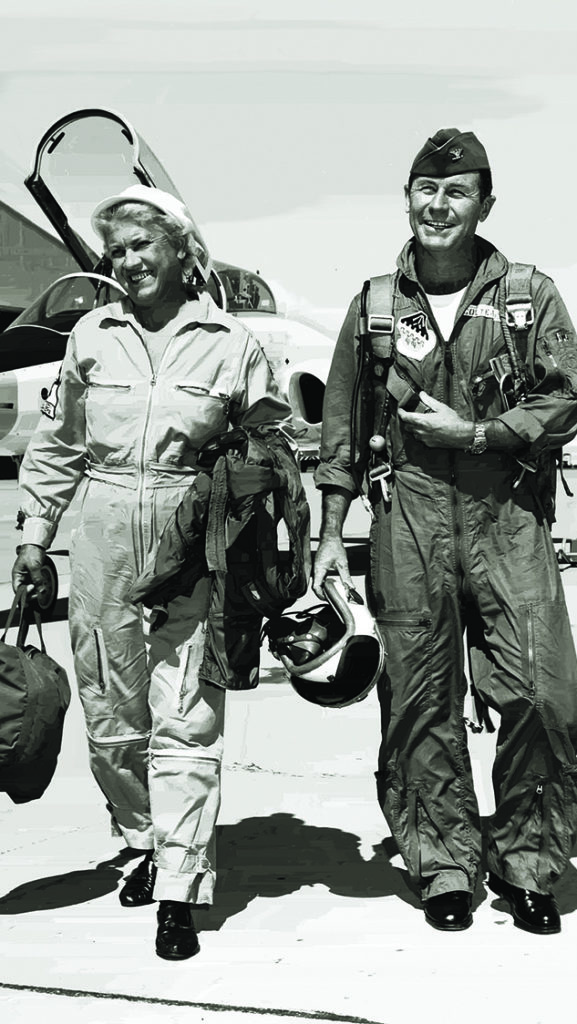

Pioneering Ninety-Nines members strongly influenced American aviation through World War II. One was Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran, an orphan from Muscogee, Florida, who grew up picking cotton, made a fortune in cosmetics, and earned a pilot’s license in three weeks. By 1938 Cochran was considered the best female pilot in the United States. On June 18, 1941, she shuttled a Hudson V bomber across the Atlantic. “Flying Grandmother” Colonel Ruth Cheney Streeter became the first director of the Women Marine Corps. Civilian members served as flight instructors, air traffic controllers, and commercial airline pilots. Many Ninety-Nines enlisted as Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) and in the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), which Cochran headed. Initially assigned to test-fly repaired planes, the women saw their duties expand to include tracking and searchlight missions, glider towing, flying radio-controlled target planes, and delivering weapons, cargo, and personnel. More experienced members flew for Grumman, testing naval aircraft. Louise Thaden became director of the Women’s Division of the Penn School of Aeronautics. As a flight instructor, Kunz trained several hundred U.S. Navy fliers at Rhode Island State Airport. Edith Folz Stearns served in the Air Transport Auxiliary, shuttling military aircraft from factories to bases and maintenance depots. Omlie established 66 flight schools in 46 states, including the facility in Tuskegee, Alabama, at which African-American airmen trained. Mary Von March conducted final inspections of Pratt-Whitney engines powering B-24 Liberator heavy bombers. Barnes headed the Women’s Air Reserve.

For secret postwar aviation projects, the U.S. Defense Department took over an airport that Barnes owned near Muroc Air Force Base—now Edwards Air Force Base—in Southern California’s Mojave Desert.

Nearby, Barnes opened Rancho Oro Verde Fly-Inn Dude Ranch, whose rustic bar became a test-pilot hangout made notorious as the Happy Bottom Riding Club by Tom Wolfe in his 1979 book The Right Stuff, a best-selling paean to the test-pilot culture from which the American space program emerged in the 1950s (see sidebar below).

Trained by U.S. Air Force aviator Chuck Yeager, Cochran in 1952 became the first woman to break the sound barrier. At the controls of a Canadian-built F-86 Sabrejet she set a world record of 652 miles per hour over Edwards Air Force Base. From 1949 through 1977, Cochran ran the annual All Woman Transcontinental Air Race. She died in 1980. The Powder Puff Derby lives on as the annual women-only Air Race Classic, a 2,400-mile, four-day event staged around North America. The next race—June 23-26, 2020; airraceclassic.org—starts in Grand Forks, North Dakota, and ends in Terre Haute, Indiana. Any woman with a pilot’s license can still join the Ninety-Nines, which has 155 chapters worldwide.

_____

Hopscotch in the Sky

The 1929 Powder Puff Derby embodied the possibilities and limitations of aeronautical technology, as well as organizers’ promotional emphasis. The opening leg was Santa Monica to San Bernardino, California. Day 2 hopscotched through Calexico, California, and on to Yuma and Phoenix, Arizona. Day 3 took 208 miles to Douglas, Arizona. Day 4 was to El Paso, Texas, via Columbus, New Mexico. On Day 5, the fliers crossed Texas via Pecos,  Midland, Abilene, and Fort Worth. On Day 6, pilots flew to Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Wichita, Kansas. Day 7 took them east to Kansas City, Missouri, and East St. Louis, Illinois. Day 8 took them to Terre Haute, Indiana, and on to Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio. They finished on Day 9 at Cleveland, an airplane manufacturing mecca.

Midland, Abilene, and Fort Worth. On Day 6, pilots flew to Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Wichita, Kansas. Day 7 took them east to Kansas City, Missouri, and East St. Louis, Illinois. Day 8 took them to Terre Haute, Indiana, and on to Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio. They finished on Day 9 at Cleveland, an airplane manufacturing mecca.

_____

Dames in Space

The Mercury 13 was a short-lived secret attempt to put female pilots into space. Dr. William Randolph “Randy” Lovelace II, head of a NASA special committee on bioastronautics, who tested the Mercury 7 male astronauts, thought women’s smaller frames and lower oxygen needs would make them great astronauts. Oklahoma-born Ninety-Niner Geraldyn “Jerrie” Cobb was the ideal candidate. First to qualify for Mercury 13 in 1961, Cobb, 29, passed the same physical and psychological testing as male candidates. In a sensory deprivation test, floating in darkness for 9 hours and 40 minutes, Cobb’s results outdid those of the Mercury 7 astronauts. Lovelace recruited 19 more female candidates; 13 passed the same tests as the men. Mercury 13 ran aground when astronaut John Glenn spoke at a congressional hearing. “Men go off and fight the wars and fly the airplanes,” Glenn said. “The fact women are not in this field is a fact of our social order.” The program was canceled. “I think some of them really thought they were going to be astronauts,” said Gene Nora Jessen, Mercury 13 participant and author of Sky Girls. She would go on to fly for Beechcraft. Cobb, 87, spent 30 years as a missionary flying supplies in to remote corners of South America. December 14-23, 1986, 34-year-old Ninety-Niner Jeana Yeager (no relation to Chuck Yeager), copiloted with Dick Rutan the first nonstop, non-refueled world circumnavigation aboard the Rutan Voyager aircraft. In July 1991, astronaut Eileen Collins traveled in space carrying one of Louise Thaden’s flying helmets signed by the 1929 Powder Puff Derby racers. On July 23, 1999, as the first woman to command a space shuttle, Collins brought Amelia Earhart’s scarf and a pilot license signed by Orville Wright in 1924 for Bobbi Trout, the last living Powder Puff racer, aboard Russian Space Station Mir. —Liesl Bradner

This story appeared in the December 2019 issue of American History.