“Youthful daredevils who rode side-by-side,” is how noted author Jeffry Wirt referred to the young men who joined John S. Mosby’s partisan rangers from Fairfax, Fauquier and Louden counties in Virginia. Nicknamed the “Gray Ghost” for his lightning quick raids and his ability to elude Union pursuit, Mosby came to operate with impunity in the aforementioned counties, harassing the rear of the Federal army in an area that came to be called “Mosby’s Confederacy.” His command — the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry — was not officially organized until the spring of 1863, but recruiting was never a problem. Young men from the counties whose family farms were being destroyed and ravished by Union forces, their homes occupied by Union officers, or their family members abused or disrespected were more than anxious to “join up” with Mosby who reported to no one but J. E. B. Stuart.

One such volunteer was John Henry Thomas — the son of Judge Henry Wirtz Thomas who represented Fairfax county in the state legislature before the war and served the Confederacy as the Auditor of the State. His mother was Julia M. Jackson, the older sister of James William Jackson, the proprietor of the Marshall House in nearby Alexandria, who became instantly famous for killing Col. Elmer Ellsworth when the colonel removed the Confederate flag from the hotel’s rooftop flagpole in May 1861. Jackson was in turn immediately gunned down by Ellsworth’s men, his body bayoneted and trampled — the “first martyr to the cause of Southern Independence.”

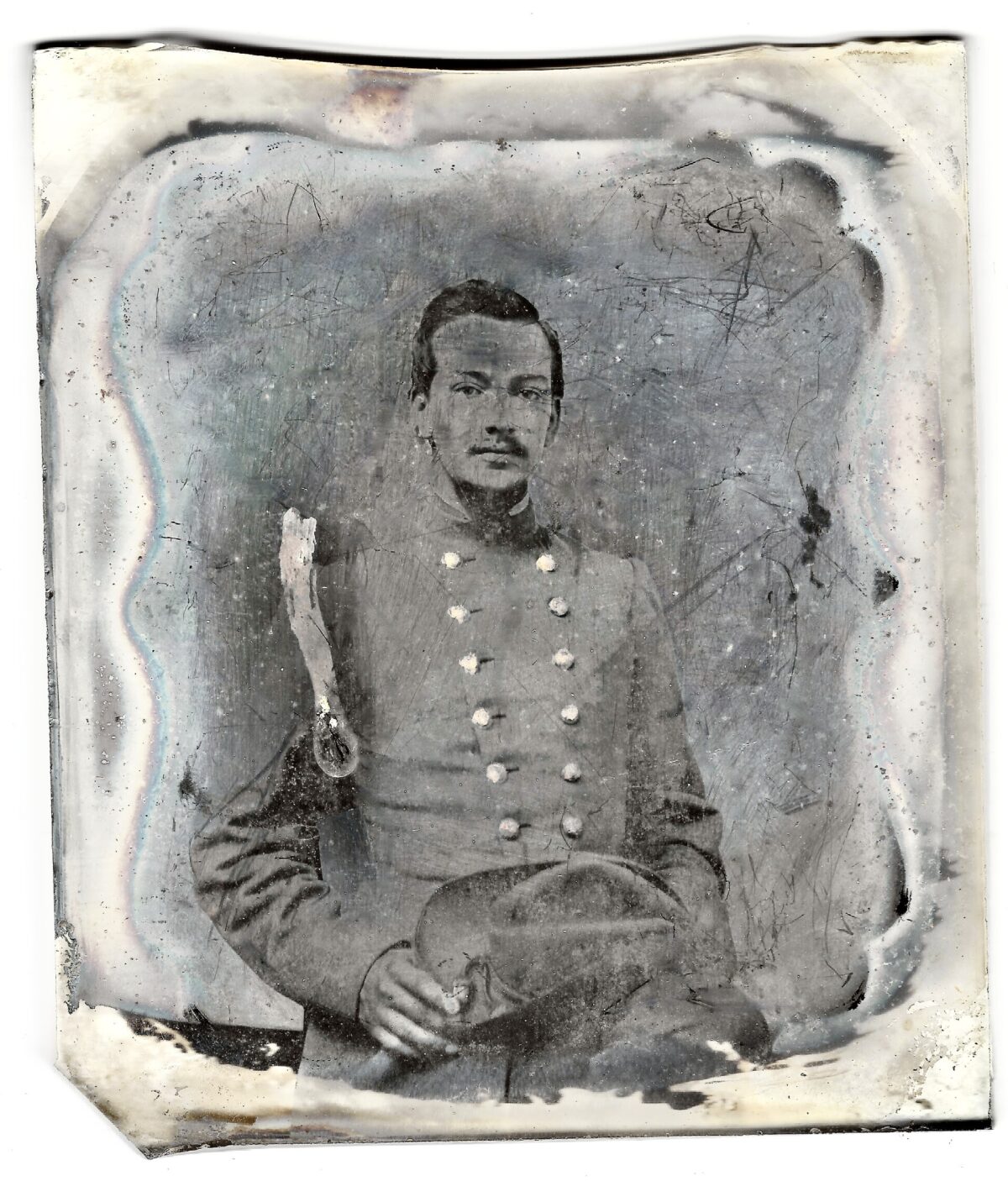

A handsome young man standing 6 feet tall, with blue eyes and dark hair, John Henry was working as a clerk when the war began and did not initially enlist until April 18, 1862, as a private in Co. G (the “Hanover Light Dragoons”) of the famous “Black Horse” 4th Virginia Cavalry. Like most other young men with connections, however, he used his father’s influence to obtain a commission from the governor as a 2nd lieutenant in Co. C of the “Irish Battalion,” or the 1st Battalion Virginia Infantry (Regulars). His commission arrived in May of 1862 while he was hospitalized at Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond while suffering from diarrhea.

By the fall of 1862, with the Union’s demoralizing loss at the Battle of Second Bull Run and Chantilly, the Army of the Potomac took up permanent quarters around Fairfax Court House, making it the headquarters of Maj. General Franz Sigel’s XII Corps, and even establishing a military hospital in the seminary. The occupation of his hometown and the “house guests” in blue who frequented his father’s home looking for room and board no doubt wore on John.

Early in 1863, when Mosby began operating with squads of limited numbers, John’s muster records indicate that he was with his regiment still hunkered down south of the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg. In March and April, however, records shows him on detached service as the Provost Marshal at Beaver Dam, Virginia — his daytime job. At night, he began to hook up with Mosby’s rangers on raids behind enemy lines. Though Mosby had as many as 800 men who rode with him by the end of April, most of the time they operated only in small squads to escape detection.

One such midnight raid in which John was known to have participated was the “Fairfax Court House Raid of March 9, 1863” resulting in the capture of Gen. Edwin H. Stoughton. The raid was summed up by William Alexander McCoy of Co. B, 1st West Virginia Cavalry in a letter dated on March 13, 1863, (published on Spared & Shared 22) which read:

The rebels made quite a daring raid on Fairfax Court House a few nights ago. They took General Stoughton and a few other officers and 40 or 50 condemned horses. I suppose they thought that they were getting a fine lot of horses but I guess that they found out their mistake as soon it became daylight for they turned several of them loose and they came back. The horses on an average were worth about $2½ a piece. There was about 40 of the rebels. All of them had our uniforms on and by some way mysterious obtained the countersign and came almost through our camp, went to Fairfax, done all they wanted to, and then returned unmolested…They are called “Partisan Rangers.” They don’t receive any pay from the Confederacy. All the horses that they capture they sell at Richmond and this is the way that they get their pay. They will not fight anything like their own number. All they want to do is to capture horses and other articles from us that they can sell.

From April 30 to August 31, 1863, whether John was present with his regiment was “not stated” in the muster rolls. It seems evident that he was not, and on Oct. 5, 1863, he “resigned his commission and joined Mosby’s command.” A letter addressed to Secretary of War James Seddon dated Aug. 28, 1863, may be found in his military file requesting authority to raise a company of cavalry “to act within the lines of the enemy in conjunction with Major Mosby & under his command.” He went on to add that he was “well acquainted with the region of country in which he is acting & am confident that, with authority from you, I can raise a Company in a short time, having had assurances given me to that effect.” Such authority may have been necessary for Mosby to accept John officially into the Rangers as he was known to insist upon no deserters joining his outfit.

As a member of Mosby’s Partisan Rangers, it understandably proves more difficult to track John’s movements and activities going forward.

However, a book by Keen & Mewborn published in 1993 entitled “43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry” informs us that John was a 4th Sergeant in Co. A and that he officially joined the Rangers in the fall of 1863. He was known to be on the Nov. 14, 1863, raid on a sutler’s wagon near Fairfax Court House and he was taken prisoner two days later and charged with plundering. The date of his exchange isn’t known. In July 1864 he participated in a raid on Point of Rocks, Maryland, and two days later at Mt. Zion Church. On Oct. 9, 1864, he led a skirmish and captured dispatches at Ashby’s Gap. He officially surrendered on May 9, 1865, and “swallowed the yellow dog” (took oath) at Alexandria.

John’s post-war activities remain sketchy. He married Fannie Gwynn and settled down in Fairfax county where he attempted to rebuild his life. The 1870 U.S. Census identifies him as a farmer but what was left of the family farm is uncertain, as a Freedman’s village and school was reportedly built on a portion of his father’s lands. By 1880 he had taken a job as a “mail agent on the Manassas branch of the Virginia Maryland railroad,” and had fathered three children — Alma M. Thomas and twin girls Ruth and Ruby.

He died eight years later in 1888 at the age of 45, his cause of death described curiously “as an illness of but three days.” The one and only obituary notice I could find for him summed up his life with the phrase, “during the war he was a member of Mosby’s battalion.”

The 6th-plate ambrotype image of John Henry Thomas is identified by a piece of paper taped to the outside of the case which reads, “John H. Thomas, son of Judge H. Thomas, Confederate 1st Lieut. under Stonewall Jackson by his daughter Alma, Fairfax, Va.” The image was sold at auction in 1997 and has been in the personal collection of my friend Jean MacCallum until recently when she sold it to me. Jean gathered most of the background material on the Thomas family and together we confirmed that Alma was actually John’s daughter, had married Henry Cox Saffell in 1896, and that she lived in the District of Columbia until her death in 1966 at the age of 93. Her advanced age when she labeled this image may account for her confusion of J. E. B. Stuart with Stonewall Jackson but the other identifiers are unmistakable.

William Griffing transcribes thousands of letters as part of his online repository of Civil War letters, Shared & Spared. For more of the compelling letters he makes available to read, visit the Spared & Shared Facebook page.