In the summer of 1885, Lee Yick, a Chinese citizen operating a laundry in San Francisco, California, refused to pay a $10 fine the city had levied for doing business without a license. A municipal court sentenced the laundryman to jail; he served a day for each dollar of the fine. That skirmish not only went to the U.S. Supreme Court but established two important principles that continue to guide American jurisprudence.

Punning on his name, Lee Yick called his laundry, on Third Street between Harrison and Folsom, Yick Wo, which in Chinese means “harmony and tranquility.” When Sheriff Peter Hopkins arrested Lee Yick, he confused the business’s name with the owner’s. Ensuing legal paperwork identified Lee Yick as Yick Wo.

San Francisco authorities fined Lee Yick for lacking a proper license—which he lacked because San Francisco refused to license any Chinese laundries, even though Chinese ran most of the city’s laundries. That bias marked only some of the opprobrium in which official San Francisco held Asians. Earlier, a city ordinance had tried to curtail Chinese laundries by saying they could operate only if at least 12 citizens living in that block approved. That rule was thrown out as unconstitutional.

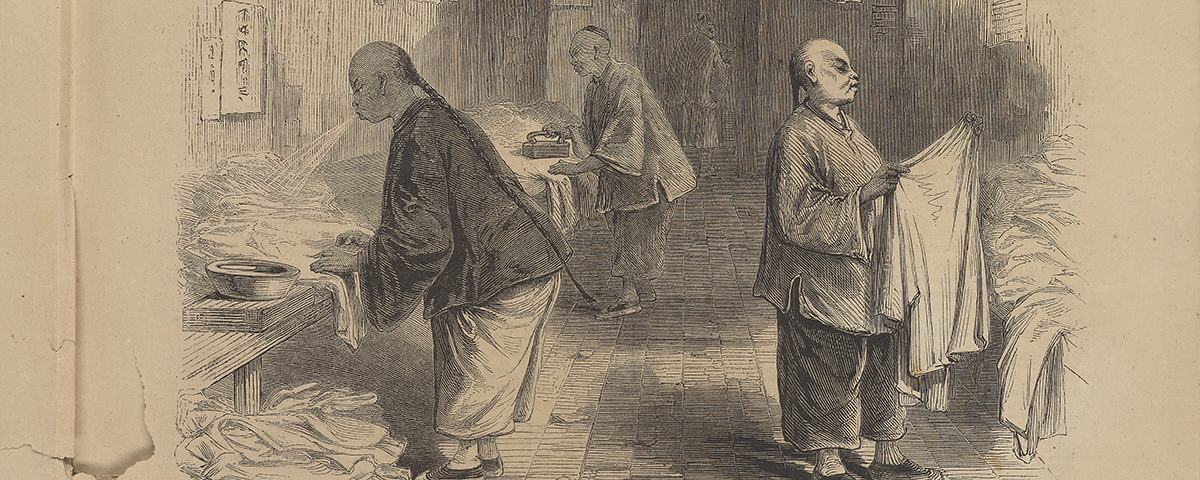

The city rebooted, this time decreeing that unless a laundry occupied a brick or stone building, it could operate only if licensed by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Of the city’s 320 laundries, 310 were in wooden buildings, but about 90 percent of San Francisco houses were wooden as well, rendering dubious the new rule’s ostensible grounding in public safety. Moreover, the city had extensive fire safety regulations and wardens routinely inspected laundries for compliance. Even more dubious was the way the city administered the new licensing requirement, turning down more than 200 Chinese applicants while with one exception allowing all 80 Caucasian laundries to stay open.

Chinese launderers stood fast. “The Chinese were very savvy,” said Mae Ngai, professor of Asian-American Studies at Columbia University. “They were organized, and they knew the laws of the country they were living in.”

The Fung Hing Hong, or laundrymen’s guild, funded a campaign to fight the licensing requirement, engaging the support of local Chinese businessmen and the Chinese consul.

Lee Yick’s was a smart choice as a test case. He had been in business 22 years, unequivocally passing annual fire safety and sanitary inspections, and actually had gone to jail for continuing to operate after having his license request rejected—evidence that the city clearly denied him the “liberty” that under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution cannot be taken away “without due process of law.”

To plead Lee Yick’s and by association other launderers’ cases, supporters hired the lawyer who arguably was the city’s most prominent: Hall McAllister, a former U.S. Circuit Court of California judge. McAllister maintained that the laundry licensing law was unconstitutional, but at every state court all the way to the California Supreme Court, judges called the contested ordinance a normal exercise of city council power. This obduracy let McAllister appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1886.

San Francisco’s Chinese had a second strategy: McAllister took an almost identical case, involving laundry owner Wo Lee, into federal court, telling U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Lorenzo Sawyer that in California courts Chinese laundrymen could not get a fair legal hearing because in that state “no judge deciding any Chinese case contrary to popular prejudice could ever hope for reelection.”

Sawyer empathized. San Francisco’s laundry licensing ordinance, lacking as it did standards for deciding who did and did not get a license, made little sense, he noted. In addition, the judge said that the city could not sugarcoat the reality of its “purpose to drive out the Chinese laundrymen and not merely to regulate the business for the public safety.” The truth—that the ordinance was part of prevailing animosity to Chinese—“must be apparent to every citizen of San Francisco,” Sawyer wrote. Nonetheless, the judge felt he had to defer to a decision upholding the city law handed down by the California Supreme Court in the Yick Wo case. So, at the U.S. Supreme Court, Wo Lee’s case was merged with Lee Yick’s, although the Court’s ruling bears the title Yick Wo v. Hopkins.

Before the justices could gauge the San Francisco ordinance’s constitutionality, they had to decide whether the 14th Amendment or any other part of the Constitution protected the laundrymen. Not only were Wo Lee and Lee Yick not United States citizens, but an 1882 federal law barred them from becoming citizens. That made no difference, the justices held. The court never had ruled on this issue, but justices had to look no further than the 14th Amendment’s wording. The germane phrase says the government may not “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” That clearly means, Justice T. Stanley Matthews wrote in Yick Wo, that in the United States, “strangers and aliens” have protection equal to that accorded citizens.

The San Francisco law the launderers were challenging did apply equally: To operate in wooden buildings, both Chinese and white laundry owners needed Board of Supervisors permission. However, Matthews explained, to be valid, any regulation must be reasonable—that is, have a legitimate reason for existing and transparent standards for judging compliance that leave no room “for the play and action of personal and arbitrary power.” Almost certainly the laundry law, lacking criteria for granting licenses, did not meet that standard.

Matthews noted that unreasonableness but ducked when deciding the issue. “In the present case we are not obligated to reason from the probable to the actual,” he wrote. Given the city’s record of saying “no” to Chinese laundrymen and “yes” to similarly situated whites, the law clearly discriminated. In the Yick Wo decision’s most oft-quoted sentence, Matthews wrote that even if a law’s wording appears fair, the Constitution bars that statute if it is administered “with an evil eye and unequal hand, so as practically to make unjust and illegal discrimination.”

This thumbs-down, while unusual for the era’s conservative court, was not hard-fought. Only four weeks after accepting briefs, the court unanimously handed down Matthews’s decision. The justices did not regard the matter as racial, but rather saw the offending regulation as an assault on the sacred right to conduct a business without unreasonable government interference.

In the 20th century, Yick Wo anchored a host of challenges to government overreach. In suits involving affirmative action, anti-sodomy laws, the rights of prisoners held at Guantanamo Bay, and others—a roster of more than 150 Supreme Court cases—petitioners have cited precedents set by Chinese laundryman Lee Yick’s refusal to pay a $10 fine.