From June 1942 through 1945 frontline American soldiers filed stories and photographed World War II and its aftermath for a select readership—themselves

Solomon Islands, spring 1944. Sergeant Barrett McGurn moved cautiously atop Hill 260, the notorious “Bloody Hill” northeast of the Empress Augusta Bay beachhead on Bougainville Island. Suddenly, a Japanese knee-mortar shell exploded in front of him with a bright red-orange burst, knocking him onto his back. The ground shivered, as did his hands. A reporter for Yank, the Army Weekly, McGurn watched the smoke dissipate and then took out a pencil and notepad to record how it felt to take a direct hit. But he could find no dry surface on the pad—the paper was drenched in the blood pouring from his face and chest. McGurn felt no regret. After all, he was a soldier. But he was also a reporter. Perhaps I can remain conscious long enough to dash off a dispatch for Yank, he thought. Then he passed out.

Yank was the brainchild of Egbert White, a World War I infantry veteran who’d written for the American military newspaper Stars and Stripes. Tracing its origins to a Civil War–era regimental newspaper, the latter publication saw its heyday in 1918 and ’19, when a reported half million soldiers turned to it for news on matters concerning the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front. It remains in print today. As a complement to Stars and Stripes, White envisioned a magazine written in the authentic voice of enlisted soldiers—a new magazine for a new war. White’s writers, photographers and artists would understand the ordeal of the enlisted man because they would wear the same uniform, have the same lowly ranks, be excluded from the same officers’ clubs and endure the same risks, indignities, fears and frustrations.

In April 1942 the Army accepted White’s proposal, commissioned him a lieutenant colonel and gave him oversight of the publication. He held the post only briefly, however, as that September he was relieved from his post for lack of proper judgment after allowing one of his writers to publish an unflattering piece about First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. The Army sent White to oversee the Mediterranean office of Stars and Stripes. Replacing him at Yank for the duration of the war was Joe McCarthy, a former sportswriter from Boston (not to be confused with the later U.S. senator from Wisconsin).

Yank—a name picked for its simplicity—was headquartered at 205 E. 42nd St. in New York City. The Army recruited prospective staffers from the ranks, leaving it to McCarthy to pick those he wanted. The editor organized Yank like a military unit sized somewhere between a platoon and a regiment. McCarthy had the men do calisthenics to keep fit, and a first sergeant maintained an up-to-date duty roster of the magazine’s globe-trotting members. Staffers were required to spend at least six months in the field before returning to a rear office, as was the common practice in frontline combat units.

The Army gave Yank’s GI reporters largely free rein—barring expected wartime censorship—to write about what they witnessed in Europe, Africa or the Pacific. The opening page of the first issue solidified that promise with a letter to the troops from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. “[Yank] cannot be understood by our enemies,” he wrote. “It is inconceivable to them that a soldier should be allowed to express his own thoughts, his ideas and his opinions. It is inconceivable to them that any soldiers—or any citizens, for that matter—should have any thoughts other than those dictated by their leaders.”

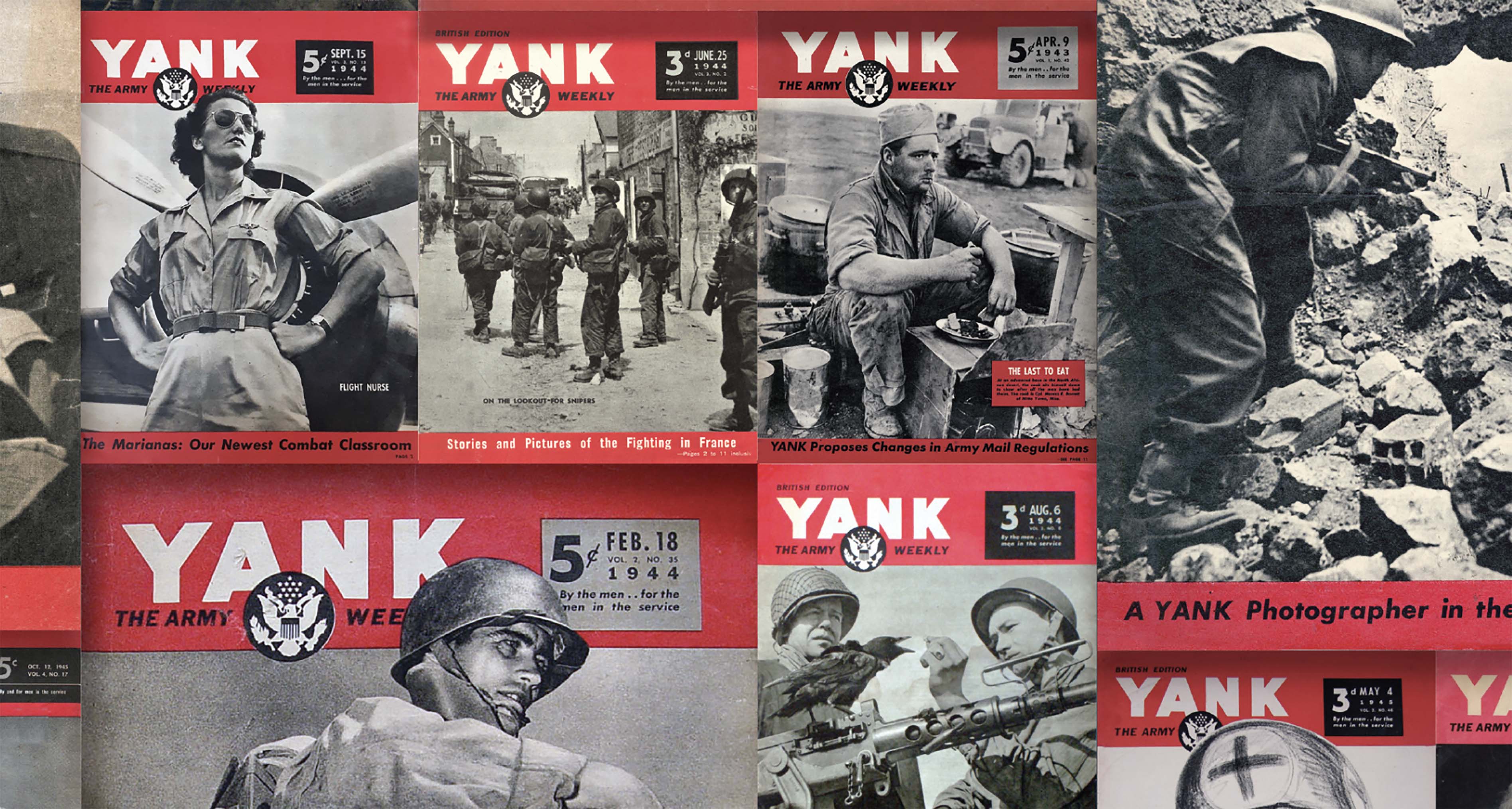

With the presidential blessing, and its philosophy and intent communicated to the Army, Yank debuted on June 17, 1942. By its final issue in December 1945 the magazine boasted 21 editions in 17 locations worldwide. Its 127 active-duty staff members filed stories from every corner of the globe in which the U.S. military operated.

The editors believed enlisted men wouldn’t trust any publication handed them free of charge, thus the 24-page weekly tabloid carried no ads and cost a nickel an issue. That was roughly half the cover price of popular periodicals at the time and usually enough to foot the magazine’s bills. Yank’s patron, the Army, absorbed any overrun costs. McCarthy was not permitted to sell Yank on newsstands, as it would pose unfair competition to commercial titles. For that reason, despite printing more than 2 million copies each week, the magazine so popular among GIs remained virtually unknown by the American public.

For its many readers Yank was a substitute for family, friends or a sweetheart back home. In addition to articles relating the grim realities of war, it touched on current events, history, sports, entertainment and sex, energizing soldiers and reminding them of the people, places and values for which they were fighting. The most popular department was “Mail Call,” a letters section in which GIs could blow off steam, air issues and seek frank answers to pressing questions. No topic was too big or too small. Scores of the 16 million Americans in service wrote in and/or scanned the section for answers to their concerns, commiserating with their brothers-in-arms worldwide.

The open bickering in “Mail Call” wavered between humorous and serious. In one issue Tec 5 Fred O. Nebling, writing from Hawaii, complained of having purchased from his post exchange a Hershey bar that contained only seven almonds, while a fellow GI got one with nine. In a subsequent issue Capt. Frank Kirby, writing from his hospital bed in West Virginia, jokingly clarified that “through some gross and unpardonable error the other soldier undoubtedly received an officer’s Hershey bar.” On a more serious note, the April 28, 1944, issue included a letter from Cpl. Rupert Trimmingham, at Fort Huachuca, Ariz., reporting with dismay that he and fellow uniformed black soldiers had been denied service in the lunchroom of a segregated railroad depot in Louisiana while two white MPs—and their two dozen German POWs—were promptly seated and served. Reaction to the letter was wholly supportive. In a follow-up in the July 28 issue the corporal said he’d received 287 letters from fellow GIs (183 of them whites, including many Southerners) expressing outrage at his mistreatment.

When it came to elevating soldiers’ spirits, no section came close to Sgt. George Baker’s beloved comic strip The Sad Sack. The title character, a lowly private first class, gave the enlisted man hope that no matter what troubles he faced, someone else—albeit fictional in this case—was always worse off. Week after week Pfc. Sack suffered aggravation and humiliations galore at the hands of aloof officers. By making light of the common soldier’s plight, Baker’s strips took the sting out of the real annoyances it depicted. “The one that still cracks me up is The Sad Sack featured at the swinging gate in a personnel office,” recalled a veteran decades later. “His paperwork is never right, so he keeps going in twice for every time he comes out.”

Baker’s Jan. 5, 1945, strip depicted Sack on patrol, stumbling across a German bunker similar to his own, with one notable distinction—the enemy bunker had a swastika flag pinned to the wall, while Sack’s wall was festooned with posters of Yank pinup girls.

Yank’s weekly pictures of beautiful women became as familiar as the M1 Garand rifle or combat helmet in soldiers’ shared war experience. For lonely GIs the pinups served as reminders of faraway wives or girlfriends, easing the frustrations of men separated from everyday social life. “Any place we could stick those girls up we did,” one former GI recalled. “When you moved out, they went into your trunk.…But the second you were in a room or a house, anything like that, and the war settled down for five minutes, back up they went.”

More than 100 actresses appeared in Yank, as Hollywood knew full well the advertising potential of their starlets. Ingrid Bergman of Casablanca fame, Lauren Bacall of The Big Sleep and Jane Russell of The Outlaw graced the pages of Yank, often in bathing suits or evening gowns. While relatively modest in comparison to pinups of later decades, they still managed to raise hackles. On several occasions soldiers wrote to “Mail Call” that their counterparts should hang up pictures of their wives and girlfriends instead of strangers. Writing from Italy just before Christmas 1944, Sgt. John F. Urwiller praised the magazine for having run a wholesome photo of actress Betty Jane Graham, “a typical American girl with the kind of beauty that every man dreams about.”

Yank was not just about “Mail Call,” comics or pinups. The feature stories, photos and illustrations produced by staffers serving alongside enlisted men on all fronts make the magazine as vital today as it was during the war.

Some of Yank’s illustrators came directly from art school, while others left long-held jobs as commercial artists. The same went for writers and photographers who’d honed their trade for popular publications before the war. Harold Ross, co-founder and editor of The New Yorker, once quipped the military weekly was to blame for one of his own especially lengthy wartime editorials. “Of course it was too long, but I have to fill space,” he said. “All my writers are on Yank!”

Distinct from their civilian counterparts, however, Yank’s staffers were fighting men, which often placed them in the thick of combat. In that regard its reporters were granted unusual freedom to roam the battlefield. Often left to their own devices, armed only with a camera, a notepad or a field typewriter, the correspondents risked life and limb so that other American soldiers understood why they were risking theirs.

In one daring exploit Sgt. Walter Bernstein, guided by partisans, walked seven days across rugged mountains through German-occupied territory to become the first English-speaking correspondent to interview Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the communist revolutionary leader fighting the Nazis in Yugoslavia. The headline-stealing coup caused quite an uproar within the Allied high command, as the territory fell within the British purview. Published in Yank on June 16, 1944, the interview was the magazine’s most heralded exclusive. Bernstein became a noted screenwriter and film producer after the war. Ironically, the very Hollywood studios who’d hired him blacklisted him in the 1950s for his favorable views on communism and the dictator who gave his career a boost.

After being struck by shrapnel from a Japanese mortar shell while climbing “Bloody Hill,” Sgt. McGurn—who would live the rest of his life with a pinhead fragment lodged in his heart—turned his experience into a cover story about the Second Battle of Bougainville. Yet, in keeping with Yank’s dictum that the reporter was the chronicler and not the story itself, McGurn downplayed his involvement and wounds, insisting in a postwar memoir, “The soldiers in the beachhead dugout were suffering far worse.” Often by McGurn’s side was his trusted Navy photographer, Chief Photographer’s Mate Mason Pawlak, whose images starkly depicted the carnage of war. Like McGurn’s stories, they did not record the experience of the man behind the viewfinder. After snapping one of his better known photos during the 1944 Battle of Angaur in the Palau Islands—an image in which a GI steps over a Japanese corpse, not daring to check for potentially booby-trapped souvenirs—Pawlak was pinned down by sniper fire, bracketed by mortars and ultimately knocked unconscious by a nearby explosion. The photographer was left partially blinded in his left eye for life.

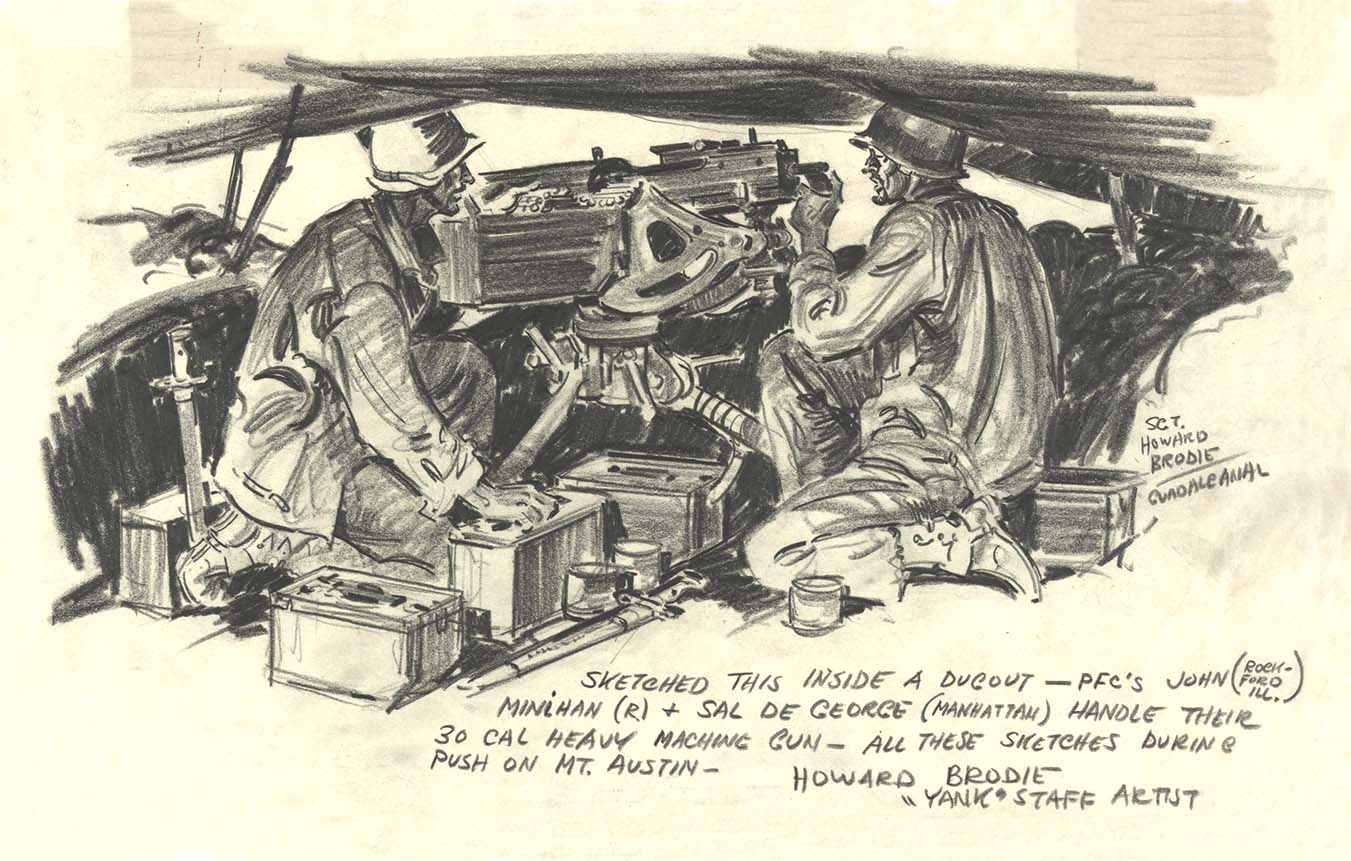

Yank’s artists claimed an advantage over its photographers in that they had the luxury of time. Not having to wait for proper lighting or rush headlong into action to capture the perfect shot, they could make mental notes and render their illustrations later. That said, they still took risks. Howard Brodie, a onetime sports artist, gained renown in Yank for his initially censored depiction of the field execution of a German prisoner. Though not released until after war’s end, the sketch showed the dead man tied to a post and slumped forward with blood and drool running from his mouth. It certainly remained true to Yank’s promise to reveal the authentic experiences of those who fought the war.

Lost to history was mention of Brodie’s Bronze Star, which he received for heroism amid the Battle of the Bulge. After the field hospital in which he was being treated was shelled, the artist swapped pencil and notepad for bandages and tourniquets as an emergency medic.

As the war expanded, so did the number of Purple Hearts presented to Yank journalists. Sometimes bringing stories of hope to their fellow soldiers cost them their lives. One of the magazine’s busiest cameramen, Sgt. Pete Paris, made history with his first-ever cover story of a black unit in combat in the early stages of the war in Africa and Sicily. In the thick of action during the D-Day landings in 1944, Paris managed to avoid machine-gun fire only to step on a land mine and have his leg torn off at the hip. He was evacuated from Normandy aboard a Navy LST but never made it back to England—the ship was bombed and sunk in the English Channel, killing all aboard. Paris received his Purple Heart posthumously.

Described by his accompanying correspondent, Merle Miller, as a photographer “from a rifle’s length vantage point,” Sgt. John A. Bushemi was known to crawl out in front of advancing GIs to get the perfect picture. His skills landed him the classified mission of chronicling the November 1943 through February 1944 campaign in the Gilbert and Marshall islands.

By the time his photographs graced the pages of Yank, however, Bushemi was dead. Mortally wounded by a mortar shell during the Battle of Eniwetok, he made a dying request of Miller to ensure his images were sent to Yank headquarters in New York.

An undated editorial from the magazine said it best. “Yank’s correspondents will go to every battlefront,” it read. “If they live, they will send back stories of the actions in which they fought. If they are killed, other correspondents will take their place.” Through the sacrifices of its writers, artists and photographers Yank remained true to its mission, faithfully depicting the American GI’s experience in World War II by presenting the individual stories of those who covered it.

Yank was given its walking papers on Sept. 25, 1945, by War Department Circular 292. Initiated by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, the document stated it was time to mute “the official voice of the enlisted man,” as war’s end had eliminated “material suitable for the mission of Yank.” After finishing work on issues that recounted soldiers’ reintegration into civilian life, the magazine published its last issue on Dec. 28, 1945, and formally closed its New York office four days later. In a final gesture of respect Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower issued Yank an “honorable discharge” certificate to publish on its closing cover, solidifying its reputation as “just one of the GIs” and ensuring its legacy.

Yank created a unique record of the American fighting man’s role in World War II. The magazine also strove to address the anticipated morale issues that come with conscripting an army of citizens, aiming to humor GIs when they were discouraged or sad, provide an outlet for their frustrations and inspire them to push through the hell of war, knowing they were not alone. It was not just the features written by its correspondents that reflected the story of American spirit and grit. The story of Yank itself—its origins, its mission and, above all else, its writers, artists and photographers—became one of World War II’s enduring tales. MH

Peter Zablocki is a New Jersey–based historian, educator and author. For further reading he recommends Yank, the Army Weekly: Reporting the Greatest Generation, by Barrett McGurn, and The Best of Yank, the Army Weekly, 1942–1945, selected by Ira Topping, as well as the Unz Review online archive of Yank [unz.com/print/yank].

This article appeared in the January 2022 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.