For years, scientists have been poring over old ship logs, scouring weather reports for clues about changes in the Earth’s climate. But there was a World War II-sized hole in their research: the hostilities disrupted commercial shipping and reduced the number of weather reports sailors were producing. Trade between the United States and Asia, in particular, ground to a halt.

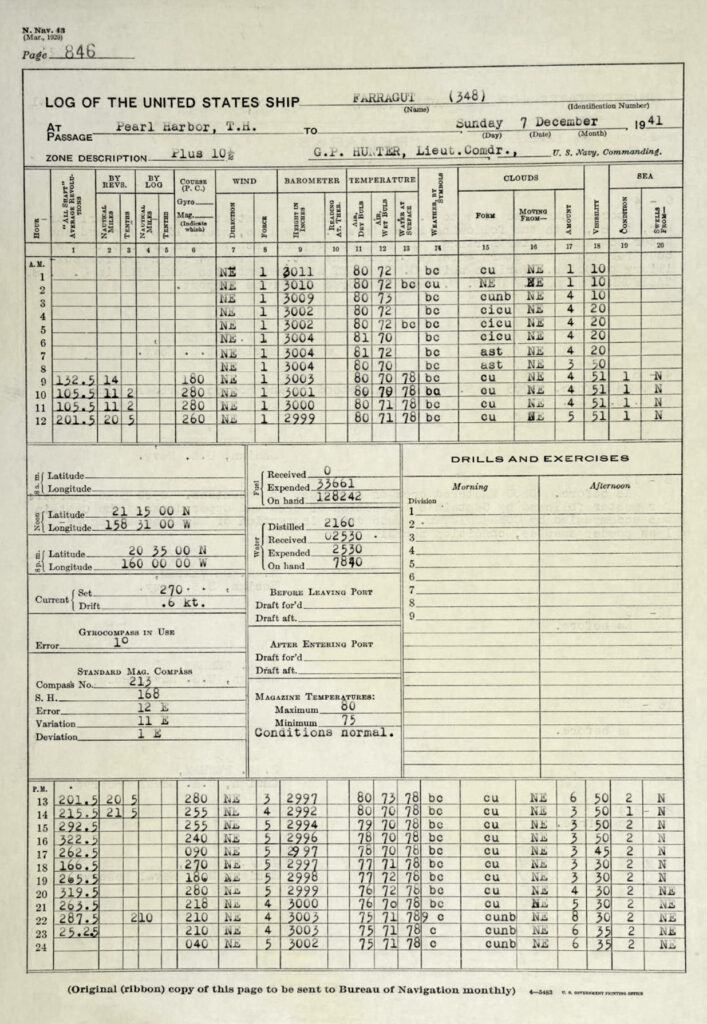

Of course, there were plenty of naval ships patrolling the Pacific from 1941-1945. And they were under orders to log their whereabouts and record the weather conditions every hour and to do so in a standardized way. However, the military classified this meteorological motherlode and made it off-limits to climate researchers. A breakthrough finally came in 2017 when the National Archives declassified 192,500 pages of U.S. Navy Command files, mostly from the Pacific and mostly from 1941 to 1946.

Now researchers faced another hurdle. Since the records were mostly on paper, they needed to be scanned, photographed, and transcribed before scientists worldwide could analyze them—a labor-intensive project indeed. Fortunately, there already existed a group of citizen-researchers, working under the name Old Weather, who had years of experience crowdsourcing the work of transcribing old ship logs to help climate scientists.

So a team led by Praveen Teleti, a climate modeler at Britain’s University of Reading, started the Old Weather-WW2 project and asked the public for help. For a year and a half, 4,050 volunteers helped digitize 630,000 records from 19 ships—three battleships, an aircraft carrier, eight destroyers, six cruisers, and a gunboat. Teleti said the project was sped along by the COVID-19 pandemic, which kept people at home with time on their hands.

The project doubled the number of weather observations available in some parts of the Pacific. The results were published in Geoscience Data Journal in September 2023. Now scientists can begin to use the data the citizen-researchers compiled to get a better understanding of changes in the climate.

Among other things, they hope to learn more about a mysterious uptick in wartime sea surface temperatures—the so-called “World War II warm anomaly”—that may, in fact, have more to do with the way sailors collected the data. And they hope to expand their understanding of Typhoon Cobra, a cyclone that hit the U.S. Pacific Fleet in December 1944, sinking three destroyers and killing nearly 800 men.