Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard almost took command of the Army of Tennessee in 1864. Almost.

“Atlanta gone,” Mary Boykin Chesnut wrote in her diary in early September 1864. “Well—that agony is over.”

With that blunt statement, Chesnut summarized how many in the embattled Confederacy digested the news that General John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee had evacuated Atlanta on September 1, allowing Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman to move in and capture the city the following day.

To be sure, Hood had struck “manly blows” to somehow save Atlanta that summer, as President Jefferson Davis later remarked. Yet both Davis and Hood came in for their share of criticism for the disaster: Hood for not preventing Sherman’s forces from finally taking the city after a bloody, four-month campaign; Davis for his decision to relieve cautious General Joseph E. Johnston as Army of Tennessee commander on July 17 and replace him with the more aggressive Hood.

General Robert E. Lee, who had commanded Hood in the Army of Northern Virginia earlier in the war, was among those not confident Hood was up to the task. As Davis began contemplating replacing Johnston, Lee expressed reluctance. When the president asked him about Hood, Lee pointedly answered that Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee had more experience. Then, on July 15, after the Confederate Cabinet had voted unanimously to relieve Johnston, Lee informed Secretary of War James Seddon that he was against the move, that if Johnston could not command an army, “we had no one who could.”

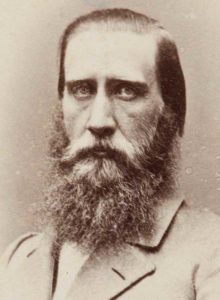

Lee, however, held his tongue after Atlanta fell; others did not. Some historians have exaggerated this “storm of criticism” against Hood, as T. Harry Williams characterized it. In his 1955 biography of General P.G.T. Beauregard, Napoleon in Gray, Williams wrote without citing a source: “At Hood’s camp many of his generals said openly that he should be replaced by Johnston or Beauregard.”

Yet Davis did in fact appoint Beauregard to a high position in the Western Theater. How that came about is an interesting story, one whose chief element has long been overlooked.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Beauregard had become dissatisfied with his role in the Confederate command structure well before Atlanta’s fall in September.[/quote]

He wanted to lead a field army, as he had done in 1861-62 at places like Manassas and Shiloh. But he had been passed over since then. “My greatest desire has always been to command a good army in the field,” he wrote a friend on August 30, 1864. “Will I never be gratified?”

By the fall of 1864, in fact, he would have settled for just about any departmental post beyond Virginia. As commander of the Department of Southern Virginia and North Carolina at this stage of the war, his headquarters were at Petersburg, Va., where he exercised no real authority with Robert E. Lee so close. Because Lee probably was aware of this, and might also have wanted to let him transfer from Virginia, he suggested in early September that Beauregard head to Wilmington, N.C., on an inspection tour. It was beneficial that North Carolina Governor Zebulon Vance had expressed interest in having the Creole take charge of the Wilmington defenses.

The administration’s uncertainty as to Hood’s future plans after the fall of Atlanta led to another possibility: Davis, as he had done with Joe Johnston in 1862-63, was considering creating a super-department in the West and putting Beauregard in charge of it—meaning, over Hood’s Army of Tennessee and also over Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor’s forces in Alabama and Mississippi.

Not only would Beauregard get away from Virginia and Lee while gaining a position of respectable, though nebulous, authority, Davis would now have an experienced general to look over Hood’s shoulder.

Some historians, such as Williams, Tom Connelly, and Jack Davis, claim that the president asked Lee to find out whether Beauregard would accept such an assignment. They base that claim, however, on suspect evidence, assuming that Davis asked Lee to talk with Beauregard because of a remarkable letter Lee had written to the president on September 19, 1864. Not one of Hood’s three principal biographers—O’Connor (1949), Dyer (1950), or McMurry (1982)—even mentions the letter (printed below), though it was an obvious effort by Lee to persuade Davis to relieve Hood and replace him with Beauregard.

“Mr. President. I have had conversation with General Beauregard with reference to the army and operations in Georgia,” Lee began his letter, indicating by his choice of words that he might well have approached Beauregard on his own.

Lee continued:

I have endeavored particularly to explain to him the necessity of the commander in Georgia developing the latent resources of the department, drawing to him all absentees from the army, concentrating its strength, restoring its confidence, and, in a word, creating the means with which he must operate against the enemy and the impracticability at present of giving him any extraneous aid.

That pretty much sums up the Confederates’ situation in Georgia after the loss of Atlanta. Strengthening and bolstering his forces for future operations was what Lee had done after Gettysburg with the Army of Northern Virginia. His implication here, that General Hood lacked the administrative ability and energy to do the same for the Army of Tennessee, reminds one of Lee’s remark to Davis the previous July: “Hood is a bold fighter. I am doubtful as to other qualities necessary.”

Of all this he is fully sensible, and while strongly impressed with the responsibility of the station and fearful of not being equal to the present emergency, being anxious to do all in his power to serve the country, he says he will obey with alacrity any order of the War Department placing him in command of that army, and do his best to expel the enemy.

The words “of that army” are important. If Davis and Lee had had any conversation about bringing Beauregard to Georgia, it would certainly not have been about his taking charge of the Army of Tennessee. Jefferson Davis had too much pride to admit that he had made a mistake in replacing Joe Johnston with Hood. Besides, as Robert Kean (head of the War Bureau in Richmond) had written a few months before, when the government wrestled over who could succeed Joe Johnston, “the only solution is to send Beauregard, but the President thinks as ill of him as of Johnston.” No, to change generals twice in two months was something Jefferson Davis was fundamentally incapable of doing.

So if the president was not considering replacing Hood with Beauregard, one must conclude that this was Robert E. Lee’s own idea. Entering the realm of presidential decision-making was most uncharacteristic of Lee. That he evidently did so here suggests Lee’s sense of urgency for the situation in Georgia, and for the cause in general. Yet the mannerly way in which Lee couched his recommendation of Beauregard was very characteristic:

Should you deem, therefore, a change in the commander of the army in Georgia advantageous, and select General Beauregard for that position, I think you may feel assured that he understands the general condition of affairs, and the difficulties with which they are surrounded, and the importance of exerting all his energies for their improvement.

Two things seem evident here. By saying, “A change in the commander of the army in Georgia….and select General Beauregard for that position,” Lee wanted to make absolutely certain the president knew that he was not recommending Beauregard for a loose supervisory role over Hood, but that he was recommending that Beauregard replace Hood. By adding, “You may feel assured,” Lee wanted to convince Davis that Beauregard knew the challenges of the situation in Georgia and felt capable of facing them.

Having made his recommendation that Beauregard be sent to Georgia, Lee took the additional step of suggesting that when the Louisianan went out west he take with him his chief of staff, chief quartermaster, and a few other officers. “His chief of staff and quartermaster are conversant with that army and country,” he added. (Notice that throughout his letter Lee has not named “that army,” much less identified General Hood as the commander to be replaced. But his intent is unmistakable.)

Lee closed in his usual gentlemanly style: “Committing this whole subject now to your Excellency’s good judgement, I am with great respect, your obedient servant, R.E. Lee, General.”

[dropcap]R[/dropcap]einforcing Lee’s remarkable letter is a memorandum drafted and signed by Beauregard himself on September 19. Probably at Lee’s request and after their conversation, Beauregard composed the memo, using just such language (“anxious to do all in my power”; “obey with alacrity”) as Lee used in his letter to the president. And like Lee, Beauregard never referred to the Army of Tennessee, stating only that he was ready to follow any War Department order “which may put me in command of that army.”

There is no evidence that Davis acknowledged or replied to this letter, which arrived just as the president was preparing to leave for Georgia. In the last week of September, Davis would visit Hood and discuss strategic plans; deal with Gen. William J. Hardee’s request for transfer to another command; and deliver uplifting speeches to the people at

whistlestops along the way. Coincidentally, on September 20, John B. Jones, the War Department clerk, entered into his diary after noting that Beauregard was in Wilmington, “[T]he whole country is calling for his appointment to the command of the army in Georgia.” Jones was no doubt being hyperbolic in declaring “the whole country,” but the fact that Robert E. Lee was calling for such an appointment is undeniable.

Davis, however, was unswayed. It is apparent that even before he met with Hood, Davis had decided to appoint Beauregard as commander of a new Military Division of the West, comprising Hood’s Department of Tennessee with Richard Taylor’s Department of East Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Davis informed Hood of his decision during his visit to the Army of Tennessee at Palmetto, Ga., from September 25-27. Nevertheless, some of Hood’s men talked of a change in the army’s leadership. An Alabama officer, Benjamin L. Posey, who penned occasional columns for the Mobile Advertiser & Register, wrote the paper after Davis had left Palmetto. “I am informed by a friend, who has the run of Headquarters secrets,” Posey divulged, “that Gen. Hood is to remain in command. The reason assigned is, that time is precious, and there is not time to get a successor.”

After explaining his idea for Beauregard’s military division to Hood, the president traveled to Montgomery, where he did the same to Dick Taylor. Then he headed back east, meeting Beauregard in Augusta, Ga., and laying out the plan. Despite his wish for a field command, the Creole accepted his new appointment.

In the meantime, someone let the cat out of the bag. A Savannah newspaper, the Republican, reported that, according to the Charleston Mercury, “President Davis has tendered to Gen. Beauregard the command of the Army of Tennessee. This result, it learns, has been brought about by the earnest intervention and counsel of General Lee.” “We hail with delight this announcement,” the Republican declared, “because the appointment of this gallant chieftain will have the effect of inspiring confidence among the troops of that army.” Others chimed in. “It is deemed certain that Gen. Beauregard will go to Georgia,” declared the Augusta Chronicle & Sentinel on September 30; “this is an auspicious sign.” But then the press backtracked. The Mercury opined on September 26 that “the President has gone to the army in Georgia to endeavor to arrange matters without putting General BEAUREGARD in command—that is, to reconcile, if possible, the army to General Hood’s continuation in its command.”

That is exactly what happened. Davis kept Hood, and Beauregard watched over Hood’s next campaign, which would take the Army of Tennessee into its home state and to the battlefields of Franklin and Nashville.

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]e will never know whether Beauregard would have done better than Hood in command of the Army of Tennessee following Atlanta’s capture. A few years ago, the Civil War community was pleasantly surprised by news that a descendant, Stephen M. Hood, had discovered a previously unknown cache of John Bell Hood’s personal papers. Those papers have since been published, allowing us to learn a great deal more about Hood. We also will continue to learn even more about Hood by re-reading the documents that have already been before us for more than 100 years.

Longtime Atlantan Stephen Davis is author of several books on the Atlanta Campaign, including What the Yankees Did to Us: Sherman’s Bombardment and Wrecking of Atlanta (2012). Retired from his day job, he currently serves as book reviews editor for Civil War News, a monthly newspaper for enthusiasts.