The atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, has been the subject of numerous books and articles since that time, many by scientists and others who participated in the development of the world’s first atomic bombs. The personal story of Brigadier General Paul W. Tibbets, who flew the Boeing B-29 Enola Gay, and the individual accounts of its crew members have also been published since that eventful mission a half century ago.

Strangely, however, the story of the second mission, which bombed Nagasaki, has not been fully told, mostly because of the concurrent rush of events leading to Japan’s complete surrender. Then, too, it may be because that second A-bomb strike nearly ended disastrously. It further proved the verity of Murphy’s Law that anything that can go wrong will go wrong.

Tibbets, then a colonel in charge of the 509th Composite Group, had honed his unit of 15 B-29 Superfortresses into one of the finest Air Force bombardment outfits ever assembled. Operating from Tinian Island in the Marianas, then considered the largest air base in the world, he and his crew had made a picture-perfect 2,900-mile flight, and had dropped the uranium bomb called ‘Little Boy’ squarely on target. That single bomb, weighing 8,900 pounds, wiped out nearly five square miles of Hiroshima–60 percent of the city. More than 78,000 of the city’s total population of 348,000 were killed; an estimated 51,000 were injured or missing.

It had been an exhausting 12-hour mission. After returning to Tinian, Tibbets was greeted on the tarmac by General Carl Spaatz, commander of the Strategic Air Force, who pinned the Distinguished Service Cross on his rumpled, sweat-stained flying suit. Meanwhile, U.S. President Harry S. Truman was aboard USS Augusta, returning from a conference with Winston Churchill and Josef Stalin at Potsdam, Germany. Upon hearing the news, Truman exclaimed, ‘This is the greatest thing in history!’ He promptly announced to the world the existence of an atomic bomb that had been developed under the code name, ‘Manhattan Project.’

The War Department then issued a number of press releases giving the history of the project, information about production facilities, and the biographies of key people. In an unusual example of military and press cooperation, the releases had actually been drafted by William L. Laurence, a science reporter for The New York Times, who had known about the A-bomb for several months prior to the Hiroshima mission. Apprised of the need for complete secrecy, he had visited the production facilities and had followed the group to Tinian.

Within hours, newspapers around the world were carrying stories about the bomb and the principles involved in splitting the atom. They chronicled the bomb’s development, the devastation it caused, the role of Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves in directing the Manhattan Project, and the contributions of 30,000 engineers and scientists in solving the mystery of the atom’s energy potential.

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson was one of the few top leaders who had been totally informed of the bomb’s top-secret development every step of the way, and he had approved the target selection. He announced that improvements would be forthcoming soon ‘which will increase by several fold the effectiveness’ of the Hiroshima bomb.

The populace of the target cities had been warned. Leaflets had been dropped on 11 Japanese cities on July 27, telling the citizens that America was ‘in possession of the most destructive explosive ever devised by man.’ There had been other warnings given to the Japanese during the preceding weeks, while the Twentieth Air Force’s Superforts firebombed the country’s principal industrial cities.

But the immense havoc a single bomb could produce was unimaginable, and the warnings were not taken very seriously. Just the day before, July 26, a declaration had been issued at Potsdam that notified the world of the intentions of three of the Allied nations concerning Japan: ‘The prodigious land, sea and air forces of the United States, the British Empire and of China, many times reinforced by their armies and air fleets of the west, are poised to strike the final blows upon Japan. This military power is sustained and inspired by the determination of all the Allied Nations to prosecute the war against Japan until she ceases to resist.

‘…We call upon the Government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all the Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurance of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.’

The Potsdam Declaration was debated vigorously at the highest levels of the Japanese government. A delegation was sent to Moscow to request that the Soviet Union, then still at peace with Japan, act as mediator. It was hoped that if the Soviets would agree to that role, it might be possible to negotiate terms that would be the most favorable to Japan.

There was great dissension among the Japanese military leaders, for few wanted to submit to a demand for unconditional surrender. Senior diplomats and influential citizens, however, privately urged Marquis Koichi Kido and members of the Japanese cabinet to take advantage of the offer in order to bring a prompt end to the war. On the other hand, War Minister Korechika Anami and the chiefs of the army and navy staffs adamantly refused to accept the terms of the Potsdam agreement. The result was that the Japanese government appeared to ignore the Allied declaration. There was no suspicion that the declaration itself constituted a warning that the most devastating weapon ever devised would be forthcoming. The people of Hiroshima tragically learned otherwise.

Because of the complete disruption of communications in Hiroshima after the atomic attack, the initial reports of damage were meager and fragmentary. While the world waited for their reaction, shocked Japanese officials were trying to grasp the extent of the damage. Meanwhile, President Truman issued the following statement: ‘It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air the likes of which has never been seen on this earth.’

It was known that there had been other diplomatic moves, made previously by Japanese emissaries through neutral nations, which intimated that Japan might surrender under certain terms that were unacceptable to America and its allies. But when nothing definitive was heard from the Japanese, plans proceeded to drop the second atomic bomb.

The second mission was designated ‘Special Mission No. 16.’ A B-29 would carry ‘Fat Man,’ heavier than Little Boy and more complex. The primary target was Kokura. The secondary target was Nagasaki.

The 509th’s Operations Order No. 39 of August 8, 1945, assigned Major Charles W. Sweeney, commanding officer of the 393rd Squadron, as the pilot in command of aircraft No. 297, nicknamed Bockscar. Major James I. Hopkins, Jr., group operations officer, was assigned to fly a second B-29 named Full House, which would carry photographic equipment and scientific personnel. On board would be Group Captain Leonard Cheshire, Winston Churchill’s official representative.

Captain Fred Bock, instead of flying his own plane, would pilot The Great Artiste, named for Captain Kermit K. Beahan’s ability as a bombardier and his alleged expertise with the opposite sex. That plane would be carrying the same special electronic measuring instruments used when Major Sweeney flew it on the Hiroshima flight. It would also be carrying William L. Laurence, a reporter for The New York Times who had been chosen at the inception of the Manhattan Project. His reporting would win him a Pulitzer Prize. A fourth aircraft was to proceed to Iwo Jima and stand by in case of an early abort by either of the backup aircraft.

Two weather observation planes were to proceed to the target areas one hour ahead of the strike aircraft. Since the order was to bomb visually for the greatest accuracy, it was essential that the area be visible to the bombardier.

Sweeney’s crew normally had 10 men. Three others were added: Lt. Cmdr. Frederick L. Ashworth, U.S. Navy, the weaponeer in charge of the bomb; his assistant, Lieutenant Phillip M. Barnes; and the radar-countermeasures specialist, Lieutenant Jacob Beser. Captain Charles D. Albury was the copilot; Lieutenant Frederick J. Olivi, a third pilot; Captain James F. Van Pelt, Jr., navigator; Captain Kermit Beahan, bombardier; Staff Sgt. Abe M. Spitzer, radioman; Staff Sgt. Edward K. Buckley, radar operator; Staff Sgt. Albert T. DeHart, central fire control gunner; Master Sgt. John D. Kuharek, flight engineer; and Staff Sgt. Raymond G. Gallagher, mechanic/gunner. Beser was the only man who flew on both atomic bomb missions as a member of the crew of the strike aircraft. Many of the others in the formation, including Sweeney, had flown the other aircraft on the Hiroshima flight.

The crews of the 509th had trained together for almost a year under top-secret conditions. They had first gathered at Wendover Field, an isolated base in western Utah, and then had flown individual long-range, over-water navigation missions from Batista Field, Cuba. The personnel of the 509th moved to Tinian by air and sea in late May and early June 1945, where their top-secret status was the subject of much curiosity and constant ribbing. The crews designated for the atomic missions practiced by dropping giant 10,000-pound ‘pumpkins’ on 12 Japanese targets. Each pumpkin contained 5,500 pounds of explosives.

The B-29s of the 509th had been modified to deliver the atomic bomb and were thus unable to carry conventional bombs. Instead, they carried the pumpkins, painted orange and shaped like Fat Man. The pumpkins also had been used during their Stateside training. Proximity fuses that produced an air burst, a feature of the atomic bombs, were installed. About 45 of the pumpkin bombs had been brought from the States. According to Tibbets, his crews were so accurate with them that Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, then commanding the Twentieth Air Force, ordered 100 more.

The carefully planned elements of one of the world’s most singular air units came together on schedule, backed by the highest national priority for supplies. The two atomic bombs were the result of the work of thousands of people. They had accepted the responsibility to try to split the atom, and to explore its potential as a bomb that could be controlled and released on demand.

The development of the atomic bomb can be said to have begun in the 1920s and early 1930s. It was then that several physicists, most of them in Europe, originated theories about ways to unlock the energy they believed existed within the atom. One of those physicists was Leo Szilard, a Hungarian who had fled from Nazi Germany to England in 1933. Szilard theorized that ‘in certain circumstances, it might be possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction, liberate energy on an industrial scale and construct atomic bombs.’ He urged British officials to conduct research to prove or disprove his theory.

Meanwhile, two German physicists, Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner, experimented with radioactive uranium in an effort to produce a chain reaction. Meitner fled from Nazi Germany to Sweden in 1938 and, together with Otto Frisch, passed the results of their experiments to physicist Niels Bohr, who left soon after for the United States. Bohr contacted Albert Einstein, also a refugee scientist, and winner of the 1921 Nobel Prize for physics, to explain the military potential of atomic energy.

Einstein, by then well-known in America, wrote a letter in August 1939 to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. ‘Some recent work,’ his letter said, ‘…leads me to expect that the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy in the immediate future and it is conceivable…that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed.’

Roosevelt appointed a group of scientists to an advisory committee on uranium, but at the time there was no real stimulus to proceed with any definitive action. Meanwhile, scientists in Germany and Japan were also considering the potential of atomic energy for war use. It took the attack on Pearl Harbor to stir the United States into action.

In 1942, Dr. Vannevar Bush, head of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development, confirmed to the president that an atomic weapon could be developed. The Manhattan Project was authorized. General Leslie R. Groves, a tough, no-nonsense Army Corps of Engineers officer, was put in charge.

Enrico Fermi, an Italian physicist working with a team of fellow scientists at the University of Chicago, built the first nuclear reactor on a squash court under the stands of the university’s football stadium. On December 2, 1942, the world’s first self-sustaining, controlled nuclear reaction was achieved.

There were at least two methods that could be used to produce an explosion, both expensive but possible. Extensive facilities were built at Oak Ridge, Tenn., and Hanford, Wash., to produce uranium and plutonium, the fissionable material needed for the bombs. A central laboratory to design both bombs was established at the so-called Site Y near Los Alamos, N.M., with Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer in charge.

Little Boy, 10 feet long and 28 inches in diameter, was similar to a gun in which a ‘bullet’ made of uranium 235 was fired into a target also of uranium 235. When the two collided, a supercritical mass was attained, and a chain reaction and explosion would occur. No preliminary firing tests were made.

Fat Man measured 10 feet 8 inches long and 5 feet in diameter. It contained a sphere of plutonium. Conventional explosives surrounding the plutonium were fired so that the plutonium was compressed into a supercritical mass, producing a chain reaction and an explosion. Fat Man was tested in the New Mexico desert, near Alamogordo, on July 16, 1945. A blinding explosion, the world’s first nuclear blast, was equivalent to 18,600 tons of TNT. By the time the more complicated Fat Man had been tested, most of Little Boy’s elements were already en route to Tinian.

After Tibbets returned from Hiroshima, Sweeney’s crews watched as Fat Man was loaded on August 8. Sweeney’s greatest fear, he said later, was of ‘goofing up.’ He said, ‘I’d rather face the Japanese than Tibbets in shame if I made a stupid mistake.’

Sweeney did not make any ‘stupid mistakes,’ but the second atomic mission seemed jinxed from the start. When queried recently, General Tibbets called the second mission a ‘fiasco’ through no fault of Sweeney’s.

The two target cities had been carefully selected. They had purposely not been bombed heavily by LeMay’s B-29s so that, as the after-action report noted, ‘The assessment of the atomic bomb damage would not be confused by having to eliminate previous incendiary or high explosive damage.’

Kokura, on the northeast corner of Kyushu, was chosen as the primary target for Fat Man because it was the enemy’s principal production source for automatic weapons. It was also the site of the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works and was one of the largest shipbuilding and naval centers in Japan.

Nagasaki, the secondary target, was the third largest city on Kyushu. It was also one of Japan’s leading shipbuilding and repair centers. It was not considered a completely ‘virgin’ target, however, because it had been bombed many weeks before by Twentieth Air Force bombers. Niigata was originally considered as a third target, but it was too far away from the other two cities.

The crews were given their final briefing during the early morning hours of August 9. They would cruise-climb to the bombing altitude of 31,000 feet. Meanwhile, the two weather planes would report the conditions over both targets. Radio silence between the bombers was to be absolute. If any of the planes had to ditch, rescue ships and submarines were in position; also, aircraft were on alert, to be dispatched to locate a downed plane or its crew.

With his airplane stripped of all armament except two .50-caliber tail guns, Sweeney lifted Bockscar off at 3:49 a.m., Tinian time. The flight route to Kokura was originally planned to proceed via Iwo Jima, but bad weather forced a change to Yaku-Shima in the Ryukus. En route, Commander Ashworth armed Fat Man.

When Bockscar arrived at the rendezvous point, only The Great Artiste was there. Due to poor visibility, Hopkins, in Full House, had lost contact with the other planes.

It had been agreed that Sweeney would not linger more than 15 minutes over the rendezvous point, but he circled for 45 minutes looking for Hopkins. Meanwhile, Hopkins was circling at another point many miles to the south. Breaking radio silence, Hopkins called out, ‘Chuck, where in the hell are you?’

Sweeney did not answer. Frustrated, he told the crew, ‘We can’t wait any longer,’ and turned toward Kokura with the single B-29 escort. He wanted the mission to be a complete success, but it would be difficult to call it that if the explosion were not properly documented by the photography that the equipment on Hopkins’ plane would produce. Meanwhile, in the bomb bay, something had gone wrong. The black box containing the electrical switches that armed the bomb had a red light. As long as the light blinked in a regular rhythm, it meant that the bomb was properly armed. If it blinked irregularly, something was malfunctioning.

Lieutenant Barnes, the electronics test officer, was the first to notice that the red light suddenly began to flash wildly. He and Ashworth frantically removed the black box’s cover to search for the trouble. Quickly tracing all the wiring, Barnes found the problem: the wiring on two small rotary switches had been reversed somehow. He quickly hooked them properly. It could have been worse. If it had been the timing fuses, they would have had less than one minute to find the trouble before Fat Man might have gone off.

Although Sweeney had heard fragmentary reports that the weather over Kokura would be favorable for visual bombing, it wasn’t. Instead of the three-tenths cloud cover originally reported, the city was now obscured by heavy cloud cover. In addition, smoke from a firebomb raid the previous night on nearby Yawata made conditions worse. Staff Sergeant DeHart, in the tail-gun position, reported flak ‘wide, but altitude is perfect.’ Fighters were detected on radar; Staff Sgt. Gallagher thought he saw fighters through the haze.

Lieutenant Olivi recalled what happened next: ‘We spent about 50 minutes and made three passes from different directions, but Beahan [the bombardier] reported he couldn’t bomb visually. It was at this time that the crew chief [Master Sgt. Kuharek] reported that the 600 gallons of fuel in the bomb bay auxiliary tanks could not be transferred. We needed that extra 600 gallons badly.’

They had no choice now. After conferring with Ashworth, Sweeney turned toward Nagasaki, hoping that the weather there was better. When they arrived, the city was obscured by nine-tenths cloud cover with very few holes. Ashworth and Sweeney considered bombing by radar against orders. Despite the risk of having an armed bomb aboard, they had been ordered to bring it back if they could not bomb visually. Niigata, the unofficial tertiary target, was too far away, especially considering their reduced fuel supply. No one wanted to have to ditch in the East China Sea or try to land on Okinawa, the nearest friendly base, with the armed Fat Man aboard.

‘We started an approach [to Nagasaki],’ Olivi said, ‘but Beahan couldn’t see the target area [in the city east of the harbor]. Van Pelt, the navigator, was checking by radar to make sure we had the right city, and it looked like we would be dropping the bomb automatically by radar. At the last few seconds of the bomb run, Beahan yelled into his mike, ‘I’ve got a hole! I can see it! I can see the target!’ Apparently, he had spotted an opening in the clouds only 20 seconds before releasing the bomb.’

In his debriefing later, Beahan told Tibbets, ‘I saw my aiming point; there was no problem about it. I got the cross hairs on it; I’d killed my rate; I’d killed my drift. The bomb had to go.’

When Beahan shouted, ‘Bombs away!’ over the intercom, Sweeney wheeled the B-29 around in a sharp, 60-degree left bank and turned 150 degrees away from the area as they had all practiced many times before. Approximately 50 seconds after release, a bright flash lit up the cockpit, where everyone had donned dark goggles. ‘It was more dazzling than sunlight,’ according to Olivi, ‘even with my Polaroid glasses on. I could see fires starting and dust and smoke spreading in all directions. An ugly-looking mushroom began to emerge from the center. It spread and began rising directly toward our B-29.

‘Right after the blast, we had lunged downward and away from the radioactive cloud. We felt three separate shock waves, the first being the most severe. As the mushroom cloud kept on climbing toward us, bright flames, a sickly pink, were shooting out of its interior. I had a sickish feeling in the pit of my stomach that we were going to be enveloped by the cloud. We had been warned many times about the possibility of radiation poisoning if we flew into it.

‘Actually, I think the mushroom cloud missed us by about 125 yards before we pulled away from it. The briefings and all the practice we had on evasive tactics now had special meaning.’

Reporter Laurence, flying nearby in The Great Artiste, was transfixed in awe at the scene. ‘We watched a giant pillar of purple fire, 10,000 feet high, shoot upward like a meteor coming from the earth instead of from outer space,’ he wrote later in his award-winning book Dawn Over Zero. ‘It was no longer smoke, or dust, or even a cloud of fire. It was a living thing, a new species of being, born right before our incredulous eyes.

‘Even as we watched, a giant mushroom came shooting out of the top to 45,000 feet, a mushroom top that was even more alive than the pillar, seething and boiling in a white fury of creamy foam, a thousand geysers rolled into one. It kept struggling in an elemental fury, like a creature in the act of breaking the bonds that held it down.

‘When we last saw it, it had changed its shape into a flowerlike form, its giant petals curving downward, creamy white outside, rose-colored inside. The boiling pillar had become a giant mountain of jumbled rainbows. Much living substance had gone into those rainbows.’

Major Hopkins saw the column of smoke from 100 miles away and flew toward the area after the explosion. However, the area was completely covered by clouds and smoke, hence no ground damage could be observed.

Sweeney made one wide circle of the mushroom cloud, then headed toward Tinian. Now they had a new danger confronting them. The fuel was dangerously low. They changed course for Okinawa with everyone on the flight deck watching the fuel gauges on Kuharek’s flight engineer console. Sweeney had pulled the props back to a range-extending low rpm and leaned out the fuel mixture controls as far back as he dared while he descended; he figured they would land about 50 miles short of the island. Even when they spotted Yontan Field, it still seemed likely they would have to ditch short of the runway.

While Sweeney flew, Albury called the tower for landing instructions. He received no reply. He broadcast a Mayday while Sweeney told Van Pelt and Olivi to fire every emergency flare on board. No one seemed to pay any attention. In desperation, Sweeney took the mike and shouted, ‘I’m coming straight in!’

‘Someone must have gotten the message,’ Olivi recalled, ‘because when we lined up on the approach, we could see emergency equipment racing out to the runway. We had only enough gas for one pass, so if we didn’t make it, we were going to end up in the ocean.

‘Sweeney came in high and fast–too fast. Normal landing speed for the B-29 was about 130 mph. We used up half the strip before we touched down at about 150 mph, a dangerous speed, with nearly empty gas tanks.

‘As we touched down, the plane began to swerve to the left and we nearly plowed into a line of B-24s parked along the active runway. Sweeney finally brought the plane under control, and as we taxied off the runway the No. 2 engine quit. Ambulance, staff cars, jeeps, and fire engines quickly surrounded us and a bunch of very jittery people debarked, very glad to be safe on the ground.’

What Olivi did not mention was that the airplane used up all of the runway trying to come to a halt. Sweeney stood on the brakes and made a swerving 90-degree turn at the end of the runway to avoid going over the cliff into the ocean. Beser recalled that two engines had died, while ‘the centrifugal force resulting from the turn was almost enough to put us through the side of the airplane.’

Kuharek, before refilling the tanks, estimated that there were exactly seven gallons left in them. The Nagasaki mission had taken 10 1/2 hours from the takeoff at Tinian to the landing at Okinawa. After they landed, the crewmen were told that the Russians had just entered the war against Japan.

For Sweeney and his crew, a nagging question haunted all of them: Had they hit the target? Ashworth didn’t think they had. In his anxiety about obeying the order to bomb visually, Beahan had released the weapon about 1 1/2 miles northeast of the city, up the valley of the Urakami River. The bomb had exploded over the center of the industrial area, not the densely populated residential area.

While their Superfort was being gassed, Sweeney and Ashworth commandeered a jeep and went to the base communications center to send a report to Tinian. They were refused permission to send such a message without the commanding general’s personal permission. Lieutenant General Jimmy Doolittle had been newly sent to Okinawa to oversee the arrival of Eighth Air Force units from Europe to prepare them for future combat.

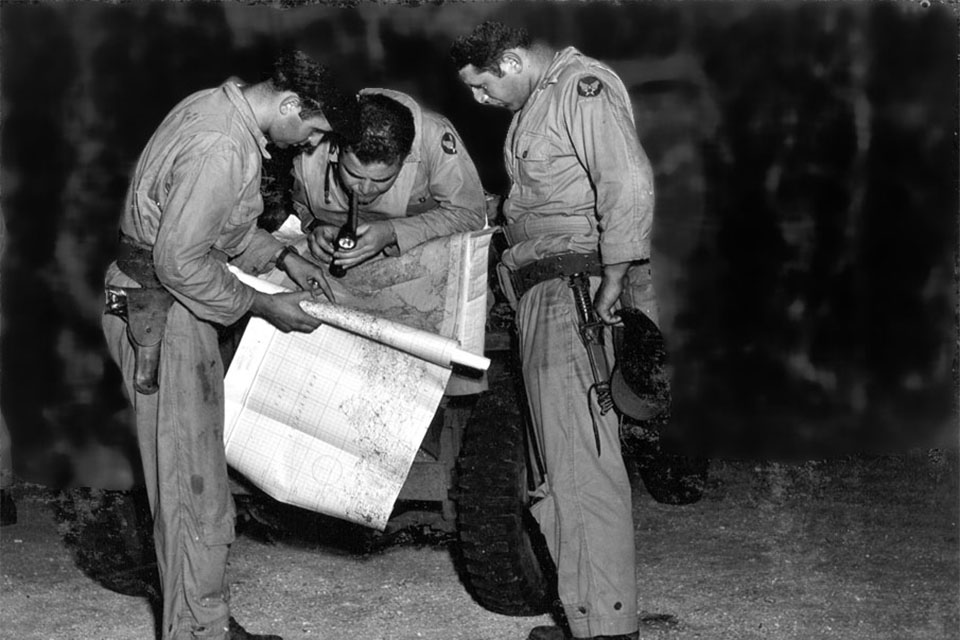

Doolittle, not privy to any of the A-bomb plans or operations, listened intently as Sweeney and Ashworth explained what had happened. Both men were nervous about telling a three-star general that they did not believe the bomb had hit the target directly. As they talked, Doolittle pulled out a map of Japan where they pointed out the industrial area over which they thought the bomb had exploded. Doolittle said, reassuringly, ‘I’m sure General Spaatz will be much happier that the bomb went off in the river valley rather than over the city with the resulting much lower number of casualties.’ He promptly authorized the communications section to send Sweeney’s coded after-action report.

Sweeney and his crew, thoroughly exhausted, took off for Tinian after a three-hour layover, and arrived there about midnight. Sweeney received the Distinguished Service Cross as pilot-in-command. All of the other crew members received the Distinguished Flying Cross as ‘members of a B-29 aircraft carrying the second atomic bomb employed in the history of warfare….Despite a rapidly dwindling gasoline reserve, they reached the target and released the bomb on the important industrial city of Nagasaki with devastating effect. The power of this missile was so great as to threaten the disintegration of the aircraft if it had been detonated while still in the bomb bay by a burst of flak, or a hit by enemy fighters, or if it was dropped while the B-29 was close to the ground, as might have occurred during engine failure.’

In his 1962 book, Now It Can Be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project, General Groves answered the question about the results of the Nagasaki mission: ‘Because of the bad weather conditions at the target, we could not get good photo reconnaissance pictures until almost a week later. They showed 44 percent of the city destroyed. The difference between the results obtained there and at Hiroshima was due to the unfavorable terrain at Nagasaki, where the ridges and valleys limited the area of greatest destruction to 2.3 miles by 1.9 miles. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey later estimated the casualties at 35,000 killed and 60,000 injured.’

The force of the Fat Man explosion was estimated at 22,000 tons of TNT. The steep hills had confined the larger explosion. Although the industrial area had been flattened, it caused less loss of life than Little Boy.

The events that followed the Nagasaki mission happened quickly. Russia declared war on Japan on August 9. On that day, Emperor Hirohito spoke to the Japanese Supreme Council. ‘I cannot bear to see my innocent people suffer any longer,’ he said. ‘Ending the war is the only way to restore world peace and to relieve the nation from the terrible distress with which it is burdened.’

The Japanese announced their acceptance of unconditional surrender on August 14. World War II officially ended at 10:30 a.m. Tokyo time, September 2, 1945, when Japanese emissaries signed the surrender document aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

Although a few pumpkin bombing missions were flown by the 509th between the second A-bomb drop and the surrender announcement on August 14, for all practical purposes, the Nagasaki mission had ended the war.

This article was written by C.V. Glines and originally published in the January 1997 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History Magazine today!