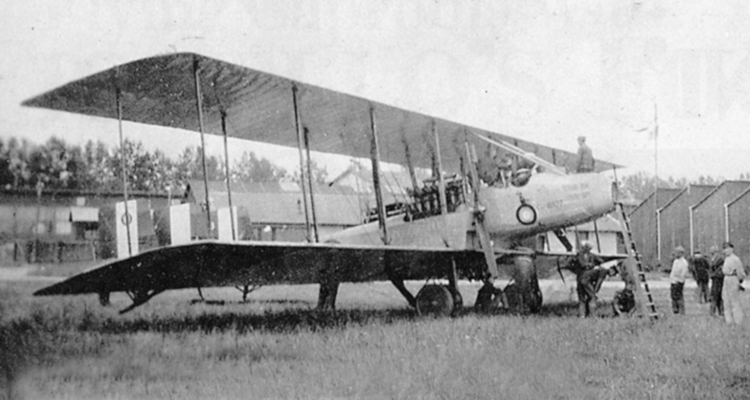

On July 25, 1918, a cumbersome, three-engine Caproni Ca.5 biplane bomber lumbered down the sod runway at Turin, Italy, lifted off and headed west toward the towering Cottian Alps. The three bundled-up crewmen knew they would have to climb well above 10,000 feet to clear that rugged barrier. And at that early stage in the development of heavy bombardment aircraft, there was no oxygen aboard and no heating equipment in their open cockpits.

Seventeen of the big Italian-made Ca.5s had been purchased by the U.S. Navy for use in France, three of them assigned to this initial effort to ferry heavy bombers across the Alps to France. One of the three had already crashed before reaching Turin.

The flight was not intended to set any records. But if this wartime ferry flight was a success, it would be the first crossing of the Alps by an American-owned airplane flown by an American crew. Aboard the Caproni was a crew of two U.S. Army Air Service (USAS) lieutenants with some experience in the Capronis, and one U.S. Navy ensign who was new to heavy bombers. Their destination was Paris.

One of the USAS pilots, 27-year-old 1st Lt. George M.D. Lewis, recorded the details of that flight — and his career as a member of what became known as ‘Fiorello’s Foggiani — in a series of letters to his sweetheart, Bertha Bert Harsch, in Narbeth, Pa. Today Lewis’ photographs, journal and letters to his beloved Bert, recently published in the book Dear Bert: An American Pilot Flying in World War I Italy, give a firsthand look into a fascinating and little-known aspect of World War I aviation.

Born in Philadelphia, George Lewis grew up in Scranton, Pa. Employed as a photographer, he worked his way through the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Architecture, completing work on his master’s degree in April 1917. The United States declared war on Germany on April 6, and Lewis promptly enlisted in the USAS. He was immediately ordered to Ohio State University for eight weeks of intensive ground school, thus missing his graduation ceremonies in Philadelphia. His mother, attired in cap and gown, accepted his diploma for him.

Completing ground school in mid-August, Lewis’ group of aviation cadets was sent to Fort Wood, near the base of the Statue of Liberty on New York Harbor’s Bedloe’s Island, where they would await shipment overseas. On September 11, Lewis and his fellow cadets left their tent city on the island and boarded SS Mongolia, a 200-foot-long, lightly armed converted passenger ship. Arriving off Halifax, Nova Scotia, two days later, he recalled, they waited for their convoy. On September 21 he recorded: Left port at sunset. The banks of the harbor were lined with cheering people and flags flying. Salutes from British and Canadian battleships, band playing ‘Star Spangled Banner’ and ‘God Save the King.’ The S.S. Kroonland and S.S. Carpathia are on our left side. Carpathia was the same ship that had come to the belated rescue of Titanic’s survivors in April 1912.

After 13 days of rotating watches for submarines, Mongolia docked at Liverpool. The group traveled to Southampton by train, then crossed the English Channel to rain-shrouded Le Havre and Paris. There they were joined by feisty 35-year-old Captain Fiorello H. LaGuardia, a U.S. representative on unpaid leave from Washington who would later become the fabled three-term mayor of New York City. Working through General John J. Pershing, LaGuardia was authorized to organize a group of several hundred American volunteers for aviation training in Italy, men who would then serve alongside Italian army troops.

In Paris the cadets entrained for a four-day journey to Foggia, Italy, where at last they would begin flight training — under American command, with Italian and American instructors. From the station, we were marched about two miles to the Campo Scuola Aviazione, Foggia Sud, Lewis wrote. We were well met and assigned to quarters in permanent barracks. We have the luxury of spring beds, sheets and wool blankets, too. The quarters have tile floors. There are shower baths and peculiar European latrines where you stand up….The camp is laid out in a comprehensive scheme with buildings radiating from the main gate and the flying field beyond. There are some 150 U.S. students here now. All speak well of the Italian officers. Major William Ord Ryan is our commanding officer.

On October 16 he wrote: We were issued helmets, fur coats and goggles. Went out to look at the hangars which are all new, as well as the machines. They are French Farmans, biplanes with pusher propellers and open fuselages. The planes were Maurice Farman M.F.11 Shorthorns. The preceding Farman design had been equipped with long forward outriggers supporting an elevator ahead of the wings, thus the nickname Longhorn. By contrast, the Shorthorn model had no forward elevator. For the rest, the M.F.11 was an ungainly 53-foot-wingspan biplane with a bathtublike fuselage and pusher engine nacelle suspended between the wings. The pilot and student were seated in tandem, exposed from the waist up to the slipstream, as there were no windscreens. Two framework tail booms supported the horizontal stabilizer and twin rudders. The complex landing gear had two pairs of wheels, each pair equipped with a jutting skid. Powered by a Fiat A.10 engine, the multistrutted M.F.11 could muster a maximum speed of 66 mph.

Lewis’ first flight came on October 17. He recalled: When my turn came, I mounted the forward cockpit. Instructor Cibolini motioned not to touch the controls….Throttle open, we rushed along till I felt a lifting sensation. Up and up. Made about 50 mi. an hour and arose to about 500 meters [1,640 feet]. Circled the field, out over the farms and back. Made a landing….My first flight was over and I had credit for 8 minutes in the air.

In succeeding days flight training — though increasingly hampered by the onset of late fall winds — continued, with 10-minute flights. In between flights, the trainees had a lot of slack time. In my room, Lewis wrote Bert on October 21, there are eight men, representing Columbia, Oklahoma, Yale, Chicago, Princeton, Dartmouth, Georgia Tech and the University of Pennsylvania. Quite a combination. All were motivated young men eager to get into action, impatient with the frequent Troppo vento non si vola (too much wind, no flying) flight cancellations. The cadets explored Foggia and nearby towns and sought out local restaurants.

In that same October 21 letter Lewis told Bert, We have not heard a bit of war news for a week. He made no further mention of the war until November 1, when he recorded in his journal, The rumor is that the Austrians, strengthened by German regiments, are threatening Northern Italy. Apparently unshaken by that possibility, he added, Played football in afternoon.

Three days later, rumor turned out to be fact. Austrian and German troops had broken through the Italian line in the northeastern corner of Italy. The Italian Third Army was in orderly but full retreat, and would fall back 60 miles in the next three weeks.

Some 350 air miles south, training of the eager-to-fight American cadets dragged on. Thus far, although there had been several accidents in the slow-moving Shorthorns, none of the Americans’ flying mishaps had proved very serious. The day after Lewis’ maiden flight he recorded: My pilot sighted a plane in trouble so we circled and landed nearby. The fellow had a broken propeller blade and came down with no real damage. On October 28 he wrote, Saw a solo man break a landing gear turning against the wind. November 6, I helped bring in a machine with a broken landing gear. Two days later, A fellow pancaked in from about 20 feet trying to glide without flying speed.

LaGuardia had decided that the morale of Italian citizens would be strengthened by seeing Americans in uniform. Accordingly, Lewis and a group of his fellow cadets were given four-day passes on November 8. Financed with a 150-lira loan from a fellow cadet (and future Hollywood director), Walter Wanger, Lewis spent his four days in Rome.

The dual lessons droned on, now extended to about 15 minutes per flight, though the M.F.11 could stay aloft nearly four hours. Finally on December 9, more than seven weeks after his first flight, Lewis soloed. His journal entry after that milestone was simply: Solo. A ‘Giro de Campo.’ Made steep climb. 6 min.

By January 1918, the Italian army had managed to establish a line along the Piave River, some 50 miles southwest of Udine. At that point Russia had collapsed, and Germany was able to move troops from that Eastern front to reinforce its armies in France and Belgium. The Western Front was stalemated, dug in and desperately awaiting promised American troops and supplies.

At Foggia some 400 American aviation cadets plugged on through their exasperatingly slow training. On January 12 Lewis earned his First Brevet — one of a series of demanding flight requirements. He wrote Bert with obvious enthusiasm: [A] most wonderful day, air clear and windless….I had a machine all to myself all morning and had most of two hours in the air. I did my spiral exercises first, then my eights and then my 45 min. at an altitude of 1,200 meters [about 3,900 feet]….On the first series of eights the barograph came loose and I had to hold it under one arm and came down with only one hand to control the machine….Now I am an Italian Pilot and am in the Second Brevet line. The clumsy barograph used to create a paper record of altitude during each flight was normally worn around the pilot’s neck. The strap had broken on this one, rendering Lewis a one-armed pilot perched in the icy slipstream with his other arm clamped on the barograph. His successful landing under those conditions was no mean feat.

In morning fog eight days later the unit suffered its first fatalities. Lieutenants William Cheney and Oliver Sherwood, flying together, collided with George A. Beach, and all three died. The following day an elaborate funeral service was held in Foggia. The American cadets marched with French and Italian troops, and respectful citizens silently lined the streets.

Through the next several weeks, Lewis completed his Second Brevet of exacting maneuvers and a raid — actually a 150-mile cross-country flight to Barletta, Bari, then back to Foggia. During a subsequent cross-country flight, his Farman’s engine quit and he landed dead stick near a sheep farm.

Lewis’ cadet contingent now moved into transitional training. In February the first Societ Italiana Aviazione S.I.A. 7B1 arrived — one of the 18 the United States had purchased for training purposes. Compared to the ungainly Farmans, the S.I.A. reconnaissance and light bombers were a step up. The 300-hp, two-place biplane was armed with two Revelli machine guns, one on a flexible mounting in the observer’s rear cockpit, the other fixed in the center of the upper wing and fired forward. With a top speed of 120 mph, the S.I.A. had been flying in combat with 13 squadrons of the Italian army’s air service. Its appearance at Foggia caused a sensation among the cadets, who were given a choice of flying the nimble S.I.A. 7B1 or Caproni heavy bombers. The Caproni had been on the scene for some weeks by then. Compared with the snappy-looking S.I.A., the Caproni resembled a lumbering elephant. A 72-foot-wingspan, four-place biplane bomber, it had three engines, triple rudders at the end of its twin booms and six landing wheels. Most of the high-spirited cadets understandably opted for S.I.A. service. For many, it was to be an ill-fated decision.

In mid-February additional Caproni bombers arrived for training use. Rain and a warm spell had melted the field’s rare snow by that time and brought with it a swarm of flies. Architect Lewis found himself ordered by LaGuardia to supervise the making of screen doors and window screens for the camp — his first architectural commission. Lumber and screening had to be scouted up in Naples, and Lewis set out for that city on February 26. Scrounging materials and supervising their fabrication took two weeks. During the second week, on the morning of March 11, he was on hand for an Austrian air raid on Naples. He wrote of the incident: Two Zepps, 20 bombs dropped, 16 killed and 35 wounded. The next day he received word from Foggia that his commission had finally arrived. He had left the training camp with a rank equivalent to a private first class. He returned to be sworn in as a first lieutenant.

His new status did not change LaGuardia’s screen door and window mandate. Lewis was still installing them as his classmates began to receive combat assignments in March and April. In fact, he didn’t extricate himself from the screen assignment until April 24, when he finally had his first ride in a Caproni bomber, a six-minute hop with an American instructor, Lieutenant Spencer Kerr. The next day Lewis himself flew the Caproni and made his first landings in the big bomber.

By that time, the S.I.A. was acquiring a bad reputation. The upper wings of a number of planes had broken up in flight, resulting in the deaths of several Italian crews in an era when pilots did not wear parachutes. At Foggia, chief S.I.A. pilot Al Weatherhead had barely survived a 3,200-foot plunge after a stall. On March 24 U.S. Marine 2nd Lt. Jordan and Italian instructor Lieutenant Freddi side-slipped into a dive from which they could not recover. Freddi suffered deep cuts. Jordan suffered a broken arm and leg. Two days later, Jordan’s leg was amputated, and the following day he died. A rumor swept the camp that American detachment commander Major Ryan had served notice he would not fly the S.I.A. On his own, LaGuardia suspended training in the aircraft — a move for which he was later taken to task — and concentrated on training his men in the big Capronis.

On May 27 Lewis recorded that he went solo on Caproni after 16th lesson. He wrote Bert: My, but it’s some wonderful piece of machinery….The instructor asked me if I thought I could take her around without smashing up….On went the throttles and I was in the air alone, made a ‘giro’ as we call a tour and landed like a bird. What he didn’t tell her was that on that same day, Memorial Day, the detachment had held a ceremony in the main hangar honoring the six cadets who had been killed since January.

On June 15 the first Caproni squadron of 20 graduates left for combat assignments. Five days later, the second squadron left for Rome, then the Italian Front. Still enmeshed in the fly screen project, Lewis wrote, my hope is to finish with the Third Squadron, though he’d heard LaGuardia had a new architectural assignment in mind.

A month later he wrote: I am all finished with my training at Foggia, ready for the Front. News from [Harold R.] Harris that we may go to France. The next day, he added, Received orders from LaGuardia to report to Milan.

By now, LaGuardia was acting as chief of air services, U.S. Army, in Italy. Headquartered in Milan near the Caproni factory, he was coordinating the U.S. procurement and dispatch of Caproni aircraft. Production had fallen behind demand, and a new factory was to be built in Genoa. LaGuardia, ever ready to tap Lewis’ architectural expertise, ordered him to Milan to review the plant’s layout.

Lewis wrote: Very happy with prospects of leaving Foggia….Harris and Kerr are going also — to fly [a Ca.5] to France. On July 16, Lewis reported to the Caproni factory in Milan, reviewed floor space requirements, then went to Genoa to present my one-day design to Capt. LaGuardia. He wrote Bert, Am head over heels in the biggest job I ever encountered and it’s mighty interesting. That job lasted only one day. Lewis returned to Milan with new orders as second pilot on one of three new Caproni 600s — Ca.5s with three Fiat A-14 200-hp engines — to initiate a cross-Alps bomber ferry route to France.

For its Dunkirk-based Northern Bombing Group, the U.S. Navy had purchased 17 new Fiat-powered Caproni bombers. Rather than crate subassemblies for rail shipment to France, the Navy decided the Ca.5s could be flown there. The ferry flights would be made in three stages: from the factory in Milan to Turin at the eastern foot of the formidable western Alps, then across that towering mountain range to Lyon, and finally on to Orly airfield in Paris.

Most of the Northern Bombing Group’s pilots had been trained in seaplanes and had no experience with large landplanes. The Navy necessarily called on the Caproni-trained Foggiani pilots for the history-making Alpine ferry project.

On July 21 the first three American-crewed bombers took off from Malpensa airfield, near the Milan Caproni factory, bound for Turin, 75 miles southwest. Only two made it. Serial No. 11577, Navy designation B-2 — with 1st Lt. Harry Harris as pilot, Lewis as co-pilot and Navy Ensign R.S. Hudson as navigator-gunner — was the last to leave but the first to arrive at Turin. Sometime later, the second plane — No. 11587, designated B-4, flown by Lieutenants Kerr and Agar — rumbled in. The third, No. 1159, designated B-1, never arrived. Piloted by Air Service Lieutenants Fred Lambert and Nat Robertson, that third bomber strayed off course. Lost, Lambert attempted a landing at Bra, some 25 miles south of Turin, and crashed. Lambert himself was unhurt, but co-pilot Robertson crawled from the wreckage soaked with gasoline and with a sprained back.

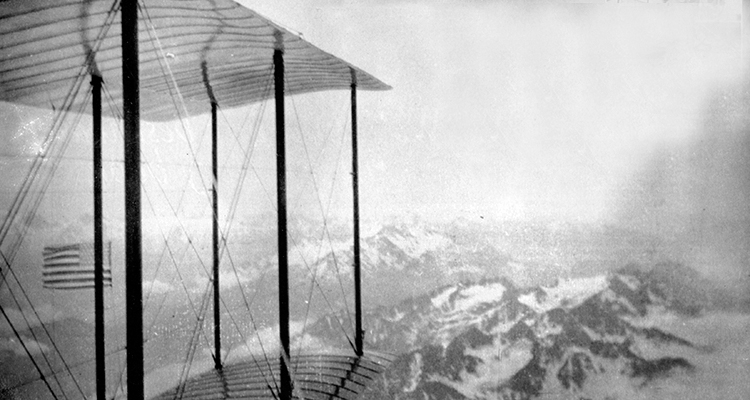

Four days of bad weather delayed the takeoffs of the two remaining Ca.5s. On July 25, with their crews insulated by layers of woolen underwear, their uniforms, leather jackets and leggings, the two heavy bombers lifted off from the Turin airport. Lewis was elated to be flying with Harris, whom he called the best pilot we have in Italy.

In those presupercharger days, the Ca.5 performed reasonably well up to 9,000 feet and was rated with an absolute 15,000-foot ceiling. Harris, Lewis and Hudson approached the Alpine rampart through the river valley west of Turin, reaching 11,500 feet over the town of Susa. The laboring Caproni next cleared 10,500-foot-high Mount Cenis and Mount Thabor by a good 3,200 feet. At close to 14,000 feet without oxygen or heated suits, the three crewmen in the Caproni suffered mightily from the cold. Ice formed in Lewis’ mustache but had thawed by the time they glided into the airfield at Lyon, France — history’s first American-owned, American-crewed aircraft to cross the Alps. They and the crew of the second-arriving Caproni, B-4 — which was piloted by Kerr and Agar — were met by cheering French and Italian officers and also by aircraft engineer Count Gianni Caproni himself, a short, jauntily mustached little dynamo in suit, tie and straw hat who had rushed over from Italy by train to celebrate their aerial accomplishment.

At 10:30 the next morning, the two Capronis took off for Paris, a 250-mile pull with an intermediate stop planned for Dijon. Kerr and Agar in B-4 soon experienced engine problems and headed back to Lyon. With fuel for 5 1/2 hours of flight, Harris and Lewis decided to skip the Dijon stop and head straight for Paris. When they were nearly there four hours later, the bomber lumbered into a blinding rain squall. At that inopportune moment, a fuel line clogged. On course but 50 miles short of Paris, the big bomber began to lose altitude.

Driving rain and mist obscured the ground. As Harris and Lewis desperately looked for a landing place, a beet field loomed out of the mist. The faltering Caproni smacked hard into the plowed ground, and the wings and fuselage crumpled.

Both Harris and Lewis were knocked unconscious. Hudson, as Lewis later recorded, was ejected from the collapsing fuselage, landed on his feet and had to run to catch up with himself. He brought us around. The three bedraggled aviators inspected their mangled aircraft — Scrambled Caproni, as Lewis termed it. Then they walked to a nearby French hospital. We were treated and my back bothered me when I got up, Lewis recalled, so we went by ambulance to an American hospital in the little town of Sens, five miles away.

Of the Caproni Ca.5s purchased by the U.S. Navy, only eight made it to their destination. The other nine were strewn across various fields from Milan to northern France, and five pilots were killed. The primary fault was not the aircraft but its unreliable Fiat engines.

In two weeks Lewis was discharged from the hospital, having meanwhile toured local flying fields and heard the thud of cannon fire eastward at the not so far away Western Front. He finally made it to Paris by car on August 12. Three days later, he and Harris left by train to return to Milan. Once there, Harris received orders to return to the States, where he was to become a test pilot.

Following the two-day rail trip back to Milan, Lewis felt poorly, [with a] headache and general disability. The next day he felt even worse. Nat Robertson, back in Milan and fully recovered from his July 21 crash, took him to the American Red Cross Hospital. Lewis, it turned out, had influenza.

This place isn’t bad, he wrote Bert a week later, but hospitals are not my place….There is a Red Cross fellow who got shot up on the Piave River. He has a lame leg and has put in almost three months here. Only a kid. That 19-year-old American, Ernest Hemingway, had been serving as an ambulance driver with the American Red Cross on the Italian Front. His experiences would later become part of the novel A Farewell to Arms.

By September 15, Lewis was well enough to sneak down a hospital fire escape and make a foray to the San Siro racetrack in the company of fellow patient George Page, three nurses and Hemingway. We didn’t win a cent, Lewis recorded, but it was great sport.

Declared fit for service in early October 1918, Lewis was assigned to the Italian 4th Squadron, 11th Bomber Group, based at Padua, 20 miles west of Venice. He began flying night raids on Austrian targets, dropping bombs and propaganda leaflets. The Austrians had bombed Padua, and the city was blacked out at night, making travel to and from the airfield after dark a hazard in itself. By mid-October, Lewis was aware something big was about to break. Planes are being brought in from other fields, he wrote. We are seeing more action every day.

Despite rumors of an impending armistice, Italian and British troops began an offensive on the 24th against the Austrian line along the Piave River. The next day Lewis wrote: All planes out and loaded with bombs. Off at 10 a.m. in big formation over Austrian lines. Bombed a town [Conegliano] about 5 miles beyond the Piave. Heavy gunfire. On the 27th all 11th Group squadrons were sent out on another daylight raid in support of the advancing Allies. Caproni Ca.3 No. 4071, of the 6th Squadron, crewed by Lieutenants Coleman F. DeWitt, James L. Bahl, Jr., and Vincezo Cutello, and Sergeant Jarcisio Cantarutti, was attacked by five Aviatik D.I pursuit planes of Fliegerkompagnie 74J, and shot down by 1st Lts. Roman Schmidt and Imre von Horvath. DeWitt was posthumously awarded the Medaglia d’Oro al Valore Militare, Italy’s highest medal.

On October 29 Italian and British troops crossed the Piave and captured Conegliano, and the Austrians fell back in full retreat. As target after target was taken by the advancing Allies, the Caproni missions were halted. On November 3 Austria concluded an armistice with the Allies. Lewis wrote on November 5: My dear Bert, Liberation Day in Italy….Bands playing, flags flying. The Italians, with Allied help, had won their part of the Great War a full week ahead of the November surrender in the West.

On November 15 all the surviving American Caproni pilots assembled at San Pelagio Airfield, Padua, where each was awarded the Italian War Cross. After nearly a month of hurry up and wait, Lewis and his group boarded SS Cartago at Bordeaux, debarking at New York Harbor on December 31.

Discharged from the U.S. Army on January 15, 1919, Lewis returned to Scranton and began his architectural practice. In April 1920, with fellow Caproni veteran Nat Robertson as best man, Lewis married his beloved Bert. They settled in Waverly, a Scranton suburb, and raised six children. Over the years, Lewis and his partner, Edward H. Davis, designed many of the Scranton area’s banks, schools, country clubs and estate homes.

Though he never flew again, Lewis designed Scranton Municipal Airport’s hangar and administration building in the 1930s. At 49, after being turned down for World War II service, he designed a mile-long defense plant for the Murray Corporation in Scranton, where Boeing B-29 wings would be fabricated. In 1987, architect George M.D. Lewis died at age 96.

The official account and memorabilia from Lewis and Harris’ historic trans-Alpine ferry flight, as well as a restored Caproni bomber, can be seen on display at the U.S. Air Force Museum at Dayton, Ohio.

This article was written by William Hallstead and originally published in the May 2003 issue of Aviation History. Lewis’ journal and letters to Bert have been preserved and made available for this article by Edward Davis Lewis, one of George Lewis’ three sons, himself an architect. For further reading, try: Dear Bert: An American Pilot Flying in World War I Italy.

For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!