Superintendent Charley Crocker’s idea of using Chinese workers on the Central Pacific Railroad didn’t sit well with his construction foreman, 37-year-old James Harvey “Stro” Strobridge. “Good God!” Stro gasped after Crocker had provided details. “Celestials? They can’t handle a pick and shovel, let alone lift one!”

A native of Ireland, Strobridge was 6 feet tall, agile, energetic and quick to lose his temper. He wore a black eyepatch, having lost sight in his right eye while working with black powder on an earlier project. Since becoming superintendent, Crocker had quarreled often with Strobridge, and now, in February 1865, he expected Stro to start cursing like a saloon bouncer. Crocker didn’t wait for the explosion. “Damn it, man!” he shouted. “The Chinese built the Great Wall of China, didn’t they! Certainly they can be useful in building a railroad, don’t you think?”

Strobridge gave Crocker’s proposal serious thought. After all, things couldn’t have been much worse in 1865. The Central Pacific was moving at a snail’s pace, having laid rails only 54 miles east of Sacramento. A shortage of reliable laborers threatened to further curtail progress. Meantime, its competitor, the Union Pacific, was laying track rapidly, having extended 250 miles west of Omaha, Neb. If the CP didn’t get a move on, the first transcontinental railroad would be largely a UP project. Instead of swearing up a storm, Stro grudgingly agreed to try 50 Chinese laborers.

After a month, the experiment was declared a success. These men—almost all shorter than 5 feet and weighing about 120 pounds—worked well in teams and, unlike many white workers, stuck to the job. Once Strobridge decided he could “boss Chinese,” Crocker instructed San Francisco–based labor contractor Cornelius Koopmanschap to scour California for an additional 2,000 Chinese workers. That was no problem. Thousands of Chinese men in northern California were searching for jobs. In the months ahead, the Chinese would prove more than just useful in building the Central Pacific; they were essential in helping a quartet of California businessmen—Crocker, Collis Potter Huntington, Leland Stanford and Mark Hopkins, the so-called Big Four—carry out this grand project.

Most of the Chinese had headed for the States 16 years earlier on hearing that one might pick up gold nuggets from any streambed in northern California. At the time of the California Gold Rush, floods, typhoons, droughts, unemployment and general poverty were plaguing southern China (including the Pearl River Delta and the city center of Kwangchow, or Canton). Thousands of men from the area packed a few belongings in straw baskets balanced on bamboo shoulder poles and sought transportation to the goldfields of America. The journey from Hong Kong to San Francisco averaged two months.

Six Chinese companies in San Francisco brought the earliest group of workers across the Pacific as indentured servants. That system didn’t work, so it was replaced by the credit-ticket system—a Hong Kong brokerage firm advanced the $40 passage, while a connecting firm in the United States found work for the immigrant and collected the voyage debt (plus interest) from his eventual earnings. As it turned out, white miners prevented the Chinese from working the profitable claims in the Sierras, and the state taxed the Chinese heavily. By 1858 the state had banned importing any more Chinese, but still they kept coming. Instead of finding gold, they found work as laundrymen, cooks and errand boys. Almost all of them tried to save money, but often they made only enough as day laborers to fill their rice bowls twice a day.

When the Central Pacific announced in 1865 it was looking for Chinese men to help build a railroad, applicants flocked to the recruiting offices. Those fortunate enough to be hired were paid $28 a month. Later, that was raised to $41, a sizable wage, even if the Chinese were expected to work from sunrise to sunset six days a week and to pay their own expenses (for food, board, opium, etc.). White laborers made the same wage, but the CP paid their expenses.

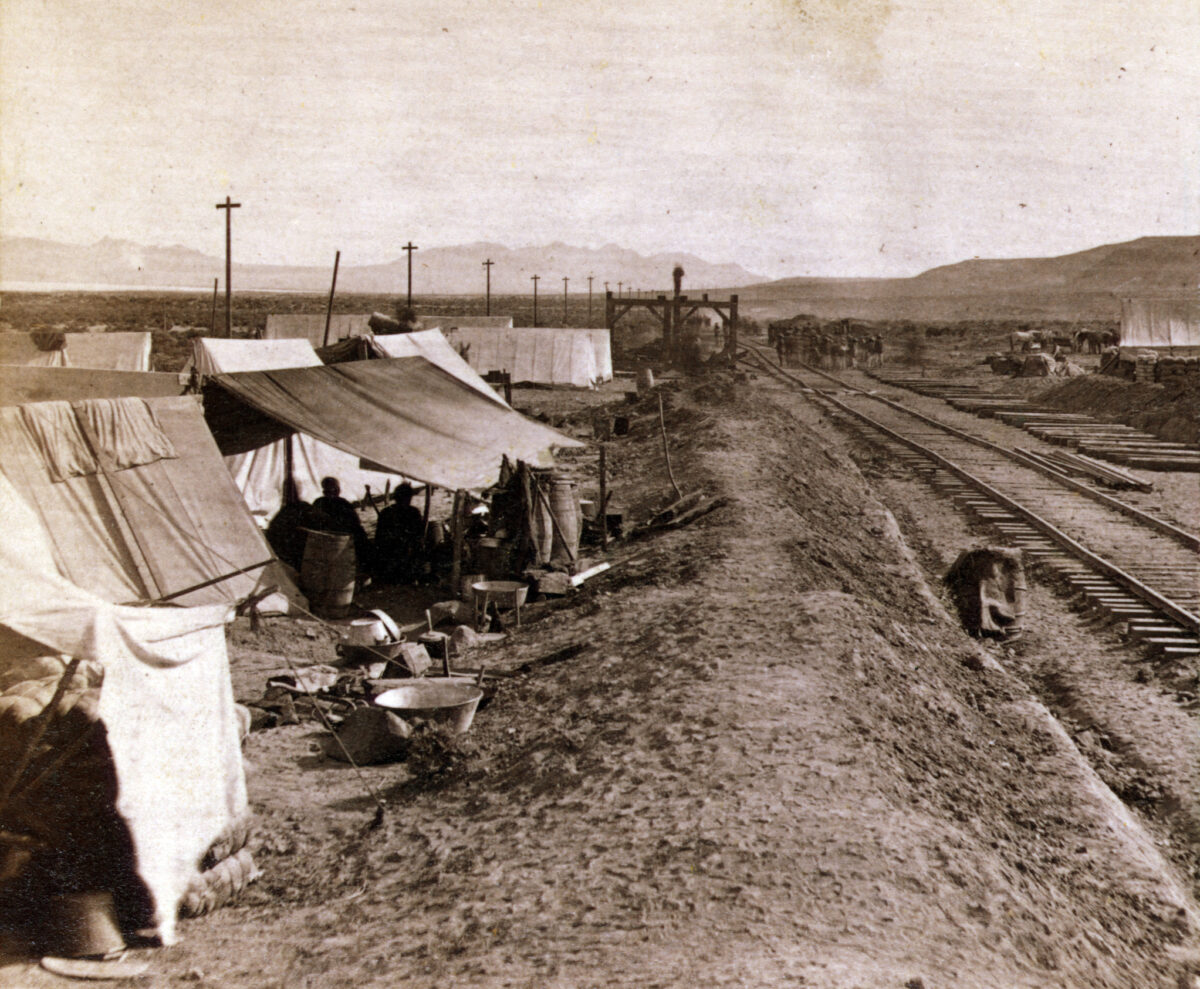

Strobridge divided his Chinese laborers into work gangs of 12 to 20 men, each with its own cook and an elected headman. The latter collected the wages for all his gang members, making deductions for food and to pay the labor contractors. Each gang also had a white, usually Irish, boss. For the most part, the whites did the skilled work, such as putting in the masonry, building the trestles and laying the rails. The Chinese cut down trees, graded and blasted.

Building the roadbed of the CP was a labor intensive, pick-and-shovel operation. Once the shovel man filled a wheelbarrow with rock or dirt, the wheelbarrow handler ran to the road edge, dumped the load and ran back for a refill as though he alone were responsible for building the road. When driving tunnels through the mountains, the Chinese had the difficult task of drilling holes for the black powder and lighting the fuses. Their work might not have been as skilled, but it was more dangerous than work done by the whites.

Stro soon bragged: “The Chinese are the best workers in the world! They learn quickly, do not fight, have no strikes that amount to anything and are very clean in their habits. They will gamble and do quarrel among themselves most noisily—but harmlessly.”

The Central Pacific faced a major problem in drilling tunnels through the Sierra Nevada granite. Eleven of the tunnels, numbered 3 to 13, lay within a 20-mile stretch between Cisco at Mile Post 92 (from Sacramento) and Lake Ridge at Mile Post 112, just west of Cold Stream Valley on the eastern slope of the summit. In the months ahead, work crews would bore some of these tunnels through steep mountain slopes buried beneath 30 feet of snow. Avalanches were frequent and swept many Chinese to their deaths.

Besides the tunneling, one of the biggest challenges for the Central Pacific came at “Cape Horn,” a three-mile-long precipitous gorge of the American River’s North Fork. Given the 75-degree slope and the river running a couple of thousand feet below, the undertaking seemed preposterous. No roads or even trails existed. Engineers ruled out boring a tunnel through the grade. Instead, crews would carve out a railroad bed along the slope, an operation that would require countless rock cuts and much blasting. Exactly how this would be accomplished remained a matter of conjecture in the summer of 1865.

One evening a Chinese headman approached Strobridge and bowed to the foreman. “What’s on your mind?” asked Stro. The man requested that Chinese workers be allowed to tackle Cape Horn. Long ago, back home, his ancestors had built fortresses in the Yangtze gorges, and he believed his people could apply those skills and techniques to the current project. He asked that reeds be sent from San Francisco to the job site so the Chinese could weave stout baskets with which to lower men from the cliff tops to do the blasting. Strobridge had no objections; no one had a better suggestion, and white workers wouldn’t do this risky work.

The reeds arrived, and the Chinese wove their waist-high baskets. Then they went about boring 2 1⁄2-inch-wide holes in the rock for the black powder charges. Once the fuses were lit, hauling crews atop the precipice would pull up the basket-borne men before the explosions. The Chinese crews set off more than 500 kegs of black powder daily, blasting a ledge on which to lay the rails. Some died in accidents, but because the Central Pacific kept no record of Chinese casualties, the number lost at Cape Horn or in the tunnels is largely speculation. The results of the hazardous work at Cape Horn were so spectacular that when passenger trains rolled through years later, they would often halt at the spot to allow tourists to gawk at the gorge and the grade.

The Chinese could take pride in their accomplishment, but there was no time to rest. Beyond Cape Horn, work crews had yet to fill hundreds of gullies and ravines and build eight trestles from 350 to 500 feet long and with spans from 40 to 100 feet high. Although constructed of sturdy timber and laced together and steadied by rows of horizontal beams, the trestles still frightened many passengers, who wondered whether the structures could support the heavy locomotives. Work slowed to a crawl in the autumn during construction of a series of tunnels near Donner Pass. Although some 2,000 white workers and 7,000 Chinese were on the project, only a handful at a time could work in the tunnels. That winter, snow further hampered the push east. In 1866 crews made some progress, sinking a vertical shaft into the midpoint of Summit Tunnel, but more heavy snows in the winter of 1866–67 again slowed the epic work.

The Chinese time and again demonstrated their adeptness at using black powder, but that wasn’t enough for Crocker and Strobridge. The Central Pacific was in a race with the Union Pacific, and the process was dragging. On January 7, 1867, Crocker wrote to Collis Huntington, the finance man of the Big Four: “We are only averaging about one foot per day on each face—and Stro and I have come to the conclusion that something must be done to hasten it. We are proposing to use nitroglycerine.” Actually, they had experimented with nitro in 1866 but found it too dangerous. Now, though, speed trumped safety. Permission was granted.

Nitro was at least eight times more powerful than an equal amount of black powder. But most of the Chinese workers did not fear nitro, and they could drill smaller holes to use it. Thus in August 1867, after a year’s labor, the skillful and courageous Chinese blasters finally managed the breakthrough of 1,659-foot Summit Tunnel (the longest tunnel and, at more than 7,000 feet above sea level, the highest point on the Central Pacific). At the same time, other Chinese were hard at work 300 miles east of the summit, grading a roadbed with the help of 400 horses and carts.

By the end of November, rail crews had laid tracks through Summit Tunnel, and a Central Pacific locomotive from Sacramento had chugged its way slowly up the grade and descended the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada. The push to Salt Lake City would be easier now. The Chinese workers—who had drilled tunnels, shoveled and blasted away snow, set up sawmills, hauled locomotives and cars and 20 tons of iron over the mountains by ox teams—were as happy as anyone. They had conquered the Sierras, a feat many engineers and politicians had thought impossible.

In 1868 the Central Pacific crews quickly laid track across Nevada. The Chinese workers had heard tales of large, menacing Indians roving the desert, and a few sources claim a number of Chinese left their jobs in fear. The problem subsided, however, when workers finally met some of the Indians and saw they clearly were not gigantic cannibals. That year the CP managed to lay almost a mile of track per day.

In March 1869, the Central Pacific entered Utah Territory and pressed on toward Promontory Summit, a flat, almost circular basin more than a mile wide, 4,900 feet above sea level and 700 feet above the Great Salt Lake, which shimmered off to the south. The race between the railroads ended in April, and at Promontory on May 10, 1869, Union Pacific’s engine No. 119 nosed up to Central Pacific’s Jupiter. An eight-man Chinese crew laid the last rail for the Central Pacific. Around noon Leland Stanford drove the ceremonial Golden Spike into a predrilled hole, providing the nation with a transcontinental rail system. A telegrapher at the ceremony tapped out a single word in American Morse code: DONE.

Bells pealed across the nation, even Philadelphia’s venerable Liberty Bell. Then came the boom of cannons—220 of them at San Francisco’s Fort Point, 100 in Washington, D.C., countless others in between. A famous A.J. Russell photograph of Union Pacific’s No. 119 and Central Pacific’s Jupiter shows hundreds of white workers standing on and around the engines. A champagne toast and handshake highlight the image. But another photo clearly shows several Chinese workers at the “Last Rail” ceremony. Some accounts mention trouble between Chinese and Irish workers (to the point of race warfare), but there is almost no evidence to support that claim. “At Promontory,” writes historian David Haward Bain in Empire Express, “Chinese, Irish and Mormons mingled in shared relief and anticipation.”

At the joyous celebration in Sacramento, Charley Crocker extended a public thank-you to the Chinese. “I wish,” he said, “to call to mind that the completion of the railroad we have built has been in great measure due to the poor, destitute class of laborers called Chinese.” The names of these Central Pacific laborers are mostly lost to history. Many of them stayed with railroad work, but as mere laborers. No doubt some of the better educated Chinese stared lovingly at engines No. 119 and Jupiter, wishing for an opportunity to become an engineer, fireman or brakeman. But those jobs were reserved strictly for white men.

Of the approximately 11,000 Chinese who ended up at Promontory, Utah Territory, some drifted back to Nevada or California, some returned to China with their savings, and others remained in Utah. Those who stayed on with the Central Pacific became section hands. They worked 12-hour shifts and in the evenings took hot baths and played their unusual Chinese music on the lo (large gong) and the nu k’in (two-stringed fiddle), according to W.A. “Pappy” Clay, whose father, Wallace Clay, served as a telegrapher for the CP at Promontory and nearby Blue Creek Station from 1884 to 1893. Born in 1884, the younger Clay spent his childhood at Blue Creek Station and shared his recollections with an interviewer in a 1969 paper titled “Personal Life of a Chinese Coolie, 1869–1899,” on file at the Utah Historical Society:

A bout every 12 or 14 miles [the Central Pacific] had a section house along to keep the track up after it was built, and at each one of these section houses, they had a section boss, and he was usually a big, burly Irishman, and then he usually had about 30 Chinese coolies working under him as section hands, and that was the setup all the way from Ogden to Roseburg, California.

My name, being Wallace Clay, was changed by those Orientals to “Wah Lee, Melicum Boy,” and I more or less lived with them from 1889 to 1892 and only slept with my parents and had breakfast at home, mostly at Blue Creek Water Tank Station, during one-half of each 24 hours….

The antiquated boxcar they lived in had been remodeled into a “work car,” in one end of which a series of small bunk beds had been built as a vertical column of three bunks, one above the other, on both sides of the car end from the floor to ceiling, so that around 18 Chinamen could sleep in the bedroom end of the car….The other end of the car served as a kitchen and dining room, wherein there was a cast-iron cookstove, with its stovepipe going up through the roof of the car and with all kinds of pots and pans and skillets hanging around the walls, plus cubbyholes for teacups and big and little blue china bowls and chopsticks and wooden table benches—about like we now find in Forest Service campgrounds—occupying the middle of the car….

The cooks built their own type of outdoor ovens in the dirt banks alongside of the sidetrack, and their stake pot spits alongside their hunk cars, where they did most of their cooking when the weather permitted. Each cook would have the use of a very big iron kettle hung over an open fire, and into it they would dump a couple of measures of Chinese unhulled brown rice, Chinese noodles, bamboo sprouts and dried seaweed, different Chinese seasonings and American chickens cut up into small pieces….When the cook stirred up the fire, the concoction began to swell until finally the kettle would be nearly full of steaming, nearly dry brown rice with the cut-up chicken through it.

Each Chinaman would take his big blue bowl and ladle it full of the mixture and deftly entwine his chopsticks between his fingers and string the mixture into his mouth in one continuous operation, while in the meantime he would be drinking his cup of tea and still more tea. I was the curious, watching kid, so the cook would ladle up a little blue bowlful for me (Little Wah Lee) and hand me a pair of chopsticks, and with them I would try to eat like the rest of my buddies. But I never could get the “knack,” so I would end up eating with my fingers, which would make the Chinese laugh, and I would get no tea.

Ogden soon became Utah Territory’s railroad hub and attracted many of the Chinese who had worked so long and so hard on the Central Pacific. They built rows of wooden structures along 25th Street, from the Broom Hotel to the railroad station, and a Chinatown quickly sprang up. Other workers headed to Salt Lake City and developed another Chinatown, known as Plum Alley. Mostly Chinese work crews built a rail line from Salt Lake City to Park City, home to yet another thriving Chinatown. Railroad construction in other places in the West, along with the steady expansion of the mining frontier, led to the rise of an assortment of Chinese communities in other states and territories, including Nevada, Colorado, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Montana and Arizona.

While the industrious Chinese work gangs who had helped build the iron road over the Sierra Nevada didn’t receive due credit in their day, they were not completely overlooked. At least one of the Central Pacific’s Big Four, Crocker, praised them; indeed, white work gangs often referred to the Chinese as “Crocker’s pets.” Railroad construction foreman Strobridge came to appreciate the Chinese as much as anyone did. Even California Governor Leland Stanford, who had gained early support among Golden State voters by speaking out against the Chinese immigrants, had this to say after completion of the transcontinental railroad: “As a class, they are quiet, peaceable, patient, industrious and economical….Without the Chinese, it would have been impossible to complete the Western portion of this great national highway.”

Freelancer and frequent Wild West contributor Robert L. Foster often researches and writes about subjects on the Utah frontier. Suggested for further reading: Empire Express: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad, by David Haward Bain; A Great and Shining Road: The Epic Story of the Transcontinental Railroad, by John Hoyt Williams; A Work of Giants: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad, by Wesley S. Griswold; and Nothing Like It in the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad, 1863–1869, by Stephen E. Ambrose.

Originally published in the June 2010 issue of Wild West.