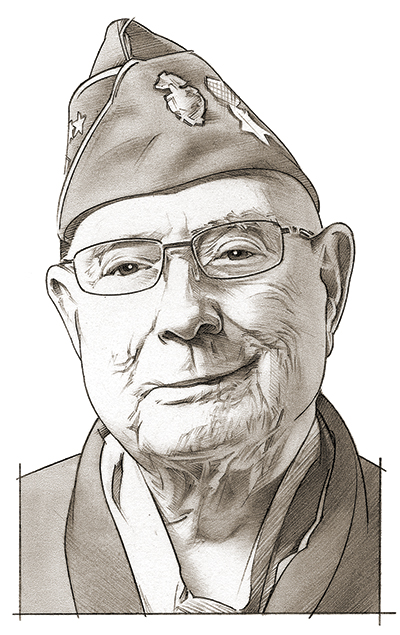

Hershel Woodrow “Woody” Williams went through hell and lived to talk about it. As a corporal in the U.S. Marine Corps he carried a flamethrower and fought bravely enough to receive the Medal of Honor. Williams, 97, is the last living World War II recipient of that distinguished award. He received it for actions on Feb. 23, 1945, during the Battle of Iwo Jima, when he took out several Japanese pillboxes amid the fierce fighting to earn the nation’s highest honor for valor in combat. At heart Williams remains a simple farm boy from West Virginia, where he was born and still lives. In 2010 he established the Hershel Woody Williams Medal of Honor Foundation to support Gold Star families and the legacy of their loved ones who made the ultimate sacrifice.

What does it take to endure combat?

Trying to explain combat is like trying to explain what it is like having a baby. If you’ve never been through it, it’s hard to understand. Even though I can explain combat, I’m not really sure someone who has never been through it could really understand the fear and anxiety and doubts you have.

I would never allow myself to think—even for a second—that I wasn’t going to make it. I would think, I’m going to get through this. I am going to get back home to my girl. I think that gave me courage I would not have had otherwise. I remember hearing about individuals who would say, “I’m never going to get off this island.” You don’t take the precautions you should if you think you’re not going to make it.

What was it like to wield a flamethrower?

Well, in January 1944 none of us had ever heard of it or seen it. We didn’t know what it was or how to use it. We did a lot of practicing and changing because we would do something that didn’t work. One time I fired it but the wind was blowing strongly toward me. Who got the flame? I did! We had to learn the hard way, but they were good lessons. I lost my eyebrows on a number of occasions. You’d think a guy would get smarter after the first time.

We used 82-octane gasoline in that thing, the same as we used in our jeeps and trucks. They had a phosphorus powder you’d mix with gasoline, and it would turn into gel. It would stick to you like glue and just kept on burning. If you tried to brush it off, all you did was spread the burn. It was terrible stuff. You could get maybe 20 yards out of it. You couldn’t aim the dumb thing because you were firing from the waist. And you only had 72 seconds of fuel. I was 21 years old and weighed 150 pounds, and it weighed 70 pounds.

‘I saw blue smoke coming out of the top of the pillbox. I crawled on top of it, and there was a pipe. They were cooking. I stuck the flamethrower down the pipe and filled the pillbox with flame’

What happened in the action for which you received the Medal of Honor?

There were a couple of pillboxes, I remember. How I eliminated the enemy at the others, I have no idea. I remember one where I was trying to crawl up close and get flame in the pillbox. They were made out of concrete and steel bars. Bazooka or artillery wouldn’t affect them.

I was crawling up this little pitch, and they were shooting at me with a machine gun. The bullets were ricocheting off my flamethrower. I moved to the right so they couldn’t shoot at me. I saw blue smoke coming out of the top of the pillbox. I crawled on top of it, and there was a pipe. They were cooking. I stuck the flamethrower down the pipe and filled the pillbox with flame.

The next one, I was getting close to the pillbox, and they came charging out toward me. How many Japanese, I don’t know. I remember seeing them with their weapons. They had rifles in their hands with bayonets. I just pointed the flamethrower at them and opened up. A big ball of flame came out. What happened at the other pillboxes, I just don’t remember.

That was the day the flag went up on Mount Suribachi. I didn’t see the first one, but I did see the second one. The Marines around me were yelling and screaming, so I turned to see what they were looking at, and I saw the flag. That’s something you don’t forget!

What other episodes from your time in service stand out?

Vernon Waters was my assistant. He and I agreed that if something happened to the other, we would get the ring from his hand and give it to the family. Back in my day you didn’t have to have a notarized statement to realize your responsibility. If you shook hands on something and made a promise, then you’d better live up to it.

He and I shook hands that we would get the ring back to my girlfriend or his dad. When I saw Vernon get hit, I ran to him to see if he was still alive. When I saw him stretched out on the ground, I knew he was dead, and that agreement came back to me. Although it was against regulations, I had to get that ring off him. When I took it off, I saw how white his finger was under it, so I rubbed some ash on it to darken the skin.

What’s the most important lesson from war you can share?

Being in the Marines was a commitment. That’s what kept you going. You committed yourself to do whatever you got to do, and you’re going to live up to that. That was instilled in us. When we were told to do something, we were only told one time. I can remember my dad saying, “I’m going to tell you this, and I’m only going to tell you one time.” He didn’t want to repeat himself. That helped me when I got to boot camp. When I was told to do something, I had no questions. I was going to do it or do the best I could. Same thing in combat. You make that commitment you are going to do whatever it takes, regardless of the situation.

‘With a flamethrower you are killing people up close, so you get that odor. That certainly gave me fits, until I finally found the Lord and sought forgiveness for having to kill people’

Describe your postwar struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Well, I got home in ’45, and I had the demons. If I didn’t keep myself occupied doing something, there would be things going through my mind. One of the best therapies I ever had was receiving the Medal of Honor. I took on a new life I never expected to live. I was raised on a farm very shy, timid. After I received the Medal of Honor, I was forced to explain how I got it. I had to talk about it. I couldn’t say, “That’s none of your business.” When I got the citation, I realized other Marines had witnessed what I had done and made it possible for me to receive the medal. I felt an obligation to them.

There is no odor on earth like burned flesh. That’s the thing that bugged me for years. I was taught growing up the value of life. With a flamethrower you are killing people up close, so you get that odor. That certainly gave me fits, until I finally found the Lord and sought forgiveness for having to kill people. That’s when I finally found peace like I never had before.

Did you specifically choose a career in Veterans Affairs to give back?

When I got home in ’45, there was no VA. We didn’t even know it existed back then. In December I got this call from a guy I never heard tell of who asked me if I wanted to work for the VA. I didn’t know what he was talking about, so I turned it down. A couple of weeks later I got a phone call from some other guy asking me if I wanted the job. This time I asked, “What does it pay?” It was good money, so I said I would take it. I had never seen so much money.

How does it feel to be the last MOH recipient of World War II?

All these years I kept asking the same question: Why me? I still haven’t found the answer. I guess the Lord is going to have to tell me. Why was I selected as the person to receive the Medal of Honor? Why not the individual who sacrificed his life? Why me? That question keeps going through my mind. I’ll be 98 in October. I’ve outlived everyone in my family. There were 464 Medal of Honor recipients in World War II. Why am I the last one? I don’t have an answer.

Do you feel a kinship with other MOH recipients?

There is a fellowship and a bond that does not exist in any other group. Almost every one, if you ask them about their medal, will say it belongs to somebody else. They didn’t do it for themselves—they did for somebody else.

To whom does your Medal of Honor belong?

I wear it in honor of two Marines who never got to come home. They provided cover for me while I went after the pillboxes but were killed in the fighting. For many years I never knew who they were. Because of computers, a couple Marines were able to learn the names of the two who died that afternoon: Cpl. Warren Bornholz and Pfc. Charles Fischer. I’ve said many times, I wear the medal in their honor. MH

This article appeared in the September 2021 issue of Military History. For more stories subscribe here and visit us on Facebook.