The Western saloon—like the European coffeehouse or colonial tavern—was an institution, an all-male preserve where a man could go for a few drinks with buddies and indulge in games of chance and fighting as side dishes. Forget the Gunsmoke portrayal of Dodge City’s Long Branch Saloon as the domain of Miss Kitty. Women were generally not permitted in saloons. A man could always find a willing partner in a dance hall, of which there were a few in every saloon district, but if he would rather just share a drink with a woman in private, he’d find his way to a wine room attached to a saloon. Each saloon boasted its special amenities—well-ventilated rooms, meals at all hours, choice whiskies, Havana cigars—but by the 1870s few had set aside a space for women such as the nook in the Palace Beer Hall in Denison, Texas, which advertised in the May 18, 1877, Daily News that its “wine room, which has recently been fitted up, is nicely furnished.” Proprietor Louis Libbie was reportedly the first in north Texas to cater to women.

Westerners did not invent the term “wine room.” A traditional feature of exclusive private clubs back East, wine rooms were tony parlors where gentlemen could enjoy fine liquors and cigars while discussing the day’s topics. The wine room of the New York Democratic Club, as described in 1902 by the New-York Tribune, was “the only place where democracy ever seems to reign supreme in the club,” where Supreme Court justices rubbed elbows with policemen, horse trainers and lawyers of “shady reputation,” and where high-rollers would periodically treat everyone in the room, announcing, “Well, boys, what’ll you have on me?”

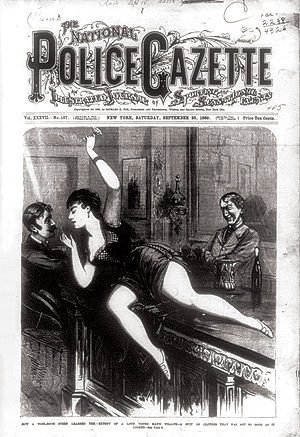

Western wine rooms sought a more gender-inclusive mix of clientele. The name itself was a way of circumventing Victorian strictures against women in saloons without driving off male customers or incurring the wrath of moral “uplifters.” Few men of the era expected or particularly wanted to turn around at a public bar to find a woman hoisting one beside him. With that in mind, some entrepreneurial proprietors fixed up wine rooms out back for female drinkers. Saloons with a second story were able to accommodate upstairs wine rooms. Either way, that section of the establishment was accessible through a separate door, posted as the Family Entrance or Ladies’ Entrance, which typically opened on an alley. Proprietors pitched them as an option for “respectable people” averse to entering by the front door. In 1904 one liberated young woman explained the appeal of the “ladies’ entrance” to a Chicago Chronicle reporter:

How is a girl ever to begin coming to the saloon if there isn’t a side entrance? It’s like this: Girls have got to have a good time. They go to the family entrance of some saloon with some boy they know to get a glass of beer or maybe of soda. They see the dancing. He says, “Let’s try it.” She thinks there is no harm in dancing with him, and there you are. That was what I did.

Conservative lawmen of the era didn’t buy the euphemism or such naive explanations. “They’re hell—that’s what they are,” one officer declared. Many others concurred. “There are several ways by which a young woman can go down the toboggan slide into the depths,” one Kansas paper editorialized. “There is no quicker and surer way than by the wine-room route.”

While upscale wine rooms might appeal to Victorian propriety, lower-end places were little more than glorified prostitution “cribs” attached to saloons. One Texas officer described the worst of the worst to a Fort Worth Telegram reporter. “Carpeted with sawdust,” the establishment was split into closet-sized spaces by partitions “little taller than a man” that offered a modicum of privacy. How one might exploit that privacy was up to the customer.

The trend quickly spread to cities across the region—Fort Worth, Dodge City, Denver, Los Angeles—any town with a vice district and a sizable female population. Many proprietors discovered their male clientele preferred to imbibe wine or claret rather than whiskey or beer and, like the ladies, preferred to share drinks in more discreet surroundings than the public barroom. While the newspaper cynics might make fun of “wine-bibbers,” no profit-minded saloonkeeper could ignore the increasing market segment. “You see, wine is gradually taking the place of beer among a certain class of drinkers,” one Chicago barkeep confided to a reporter in 1885. “It’s only a trifle more expensive than beer—that is, California wine is—and the men you meet in a wine room are a much better class of people than you find in lager-beer saloons.”

The Western wine room was never meant for connoisseurs. Most barkeeps didn’t know a Bordeaux from a Chablis, nor did their customers. The wine served was often adulterated with glucose, caramel, even coal tar. “There are tricks in all trades,” explained the same Chicago barkeep, “but most of the doctored stuff is the high-priced beverage that comes from Europe. The California wines are generally purer, but…they are not old enough [matured].”

Recognizing a good thing, saloon proprietors devoted ever more space to wine rooms. Saloons built around the turn of the century often included them in the floor plan. In a typical layout, a single closed door at the rear of the barroom led to a hallway. Off the hallway were several rooms, each equipped with a table and chairs, perhaps a sofa, some with enough floor space for dancing. A door at the other end of the hallway served as the “ladies’ entrance.” A bartender or waiter used the door between the barroom and hallway to deliver drinks and food to patrons. Of course, they were always discreet and knocked before entering any wine room. After indoor plumbing became the norm, wine rooms had their own water closets, more for the comfort of female patrons.

Mixing men and women in private rooms within a saloon produced two predictable results: 1) trysts, and 2) violence. The second naturally was related to the first. In 1889 a Dallas poet published an ode to “El Paso Mame” in the Dallas Morning News. Mame was no innocent but a frequenter of wine rooms, a boon companion of their “hellish brood” who carried a knife that “would square an insult with a life—and blood.” The poem ends with Mame laying down her life to save a young woman lured to a wine room by a pair of ruffians. “The girl was saved, but poor Mame lay dead.” The ode was as much a moral lesson as an exposé of what transpired in wine rooms. Others would write about them in far less romanticized terms.

Violence was a byproduct of the fact that on occasion drinking partners of the opposite sex were either married or attached—to others. Court records indicate that among the clientele were husbands seeking a little “extracurricular activity” and wives seeking to escape unhappy marriages. If the partner of either showed up, trouble was sure to erupt. On June 19, 1901, Fort Worth railroad foreman Henry Moore tracked wife Emma to a wine room in that burg’s red-light district, known as Hell’s Half Acre, or simply the Acre. There he found her in the company of one H.H. Russell. Henry pistol-whipped the lovers, shot both to death, then calmly surrendered to police. Such incidents gave wine rooms their growing reputation as dens of iniquity. Flagstaff, Arizona Territory, among other towns, passed an ordinance specifically barring any “prostitute, courtesan or lewd woman” from its wine rooms—which of course was their very reason for being.

Wine rooms triggered other transgressions besides murder and fornication. Set up for a secluded rendezvous with a not-so-respectable woman, a man of means could be easily drugged and robbed. One out-of-town jeweler visiting Fort Worth one Saturday night woke up the next morning with a massive headache to find his companion of the prior evening had robbed him of $150 in jewelry and $10 in cash. The woman, he complained, had “accosted” him at his cups in the wine room and asked him to buy her a drink. Being of “gallant disposition,” reported the Morning Register, he shared a drink or two with her. Suddenly feeling “woozy,” he asked the bartender to summon a carriage to return him to his hotel. The man told police he wouldn’t be able to identify the woman, then left town hurriedly. Police in towns across the region registered scores of similar complaints. Sometimes women were the victim. In 1902 an unidentified woman who had slipped into a wine room out back of Henry O’Hara’s Chicago saloon for a tryst with two men was subsequently found beaten and strangled. Police determined she’d been drugged and then killed. From her “fashionable” attire, the Chicago Journal reported, officers concluded she was “not accustomed” to such places.

By the turn of the century Fort Worth authorities had come to the conclusion the “wine room evil” was even more serious than the “saloon problem” that had long caused so much anguish. Drinking, gambling and fighting, they seemed to have decided, were less of a threat to society than the debauchery that went on in those back rooms. On the night of Sept. 20, 1902, Fort Worth Officer Sebe Maddox “rescued two 12-year-old girls” from a wine room in the wrong part of town. The girls claimed they’d been enticed by a mystery woman who’d promised them lunch and a glass of soda water. Once there, however, she’d plied them with beer, and that’s when officers arrived on the scene. The girls’ story was obviously preposterous, but it raised the alarm level. “From almost every city comes the news that the custom of saloon-drinking by women is growing,” reported the Chicago Chronicle in 1904. Despairing of their state or territorial legislatures doing anything, some cities passed ordinances further restricting or even prohibiting wine rooms. Saloon owners, bartenders’ unions, wholesale liquor dealers and anyone else who profited from such establishments fought the new laws. But the handwriting was on the wall.

Soon cities across the West began cracking down on wine rooms. Police mounted raids, rounding up everyone they found. As such raids collared as many men as women, authorities surmised there was a lot more than drinking going on behind closed doors. That in turn led them to consider any woman found in a wine room a “lewd woman.” The accused typically offered a seemingly innocent explanation for her presence. In one 1908 court case reported in Oregon’s Morning Astorian, a woman observed entering a wine room claimed she’d stopped in “to use the lavatory,” while her companion said he was “merely chatting with the barkeeper.” The prosecution questioned the woman’s credibility based on the fact she had “sauntered into the place and stepped right into the wine room as if she was very much at home.” By criminal justice standards of the day that was considered “direct evidence of guilty intention.” Despite the best efforts of prosecuting attorneys, however, the all-male juries of the day were not always willing to convict violators under the applicable ordinances. Thus police court appearances were often a roll of the dice for prosecutors.

Drinking, gambling and fighting, authorities seemed to have decided, were less of a threat to society than the debauchery that went on in those back rooms

State authorities took the initiative against wine rooms in Texas. In 1905 the 29th Legislature introduced a bill that would prohibit gambling and wine rooms in saloons and altogether ban women and minors from entering. Spurred on by prohibitionists, the Legislature also debated raising the licensing fee on saloons to a level that would effectively drive many small operators out of business. The bill divided saloon owners into two camps: those able to afford such amenities, and those who could not. A spokesman for Fort Worth’s small operators told the Evening Telegram, “It’s not fair to discriminate against the small saloon man, many of whom do not permit even dominoes to be played or keep a wine room or gambling hall, in favor of the saloonkeeper who has plenty of means.”

The most problematic loophole in state law was that it was not a crime for a woman to enter a saloon or even have a few drinks. One afternoon in early 1906 the proprietor of Fort Worth’s Senate Saloon was shocked when two well-dressed ladies sauntered in and said, “Give us a drink, bartender.” When he refused, they protested vigorously before leaving in a huff. He told the Telegram that while the women were within their rights, so was he to refuse service for reasons of propriety. Caught between the uplifters and the law, authorities declined to get involved in what they deemed a “civil matter.” That summer Police Chief James Maddox flatly stated he would not “bother about wine rooms or their visitors as long as they do not violate city law”—in other words, as long as they didn’t stray into the realm of “disorderly houses.” The Telegram wryly observed, “[County prosecutor] R.E.L. Roy says it is up to the police, the police say it is up to the county prosecutor and the sheriff, and the sheriff’s department says it is not up to them unless a complaint is filed.” It was as slick a case of passing the buck as ever seen.

Apparently, however, the heat ultimately got to the police, as that September they commenced raiding the city’s wine rooms and jailing any women apprehended. The city fathers seemed resolved to drawing the gender line at the saloon door. Question was, by what authority? Illicit trysts and public drunkenness were against the law, but it remained perfectly legal for a woman to enter a saloon. Making a case against one quietly drinking in the private back room of a saloon would prove very difficult indeed. The pushback against wine rooms lacked teeth.

Later that year, however, back-to-back political decisions put Fort Worth wine rooms on a death spiral. The first was the city’s adoption of the commission form of government, whose charter included strong prohibitions against saloons. The second was the Legislature’s adoption of the Baskin-McGregor Law, which specifically prohibited “serving liquor to women in wine rooms, tolerating lewd women in any saloon…or employing women,” except for “a wife or direct relative.” The traditionalists’ argument, succinctly expressed in a letter to the Dallas Morning News, that “a saloon is a public place in which a man sells liquor to all who wish to buy” no longer held sway. The twin measures put wine rooms squarely in the sights of both state and local authorities. Wine rooms were now under the jurisdiction of county courts, and city police were under strict orders to shut them down. The only remaining question was where violators would be prosecuted—county court or police court.

Despite the renewed offensive against wine rooms, they continued to operate in Hell’s Half Acre and other vice districts on the QT, though no longer under the pretense they were a concession to gender equality. They were now widely regarded as alternatives to cribs, the quickie houses of prostitution that once crammed the side streets off lower Rusk. In some eyes they were worse than cribs precisely because of their clientele. Decent women didn’t work in cribs, and decent men didn’t patronize them. Wine rooms, however, were Exhibit A in many a good woman’s downfall. “To these places they are frequently taken by their companions and given liquor until their senses are deadened,” wrote an 1898 committee tasked with addressing the problem, “after which the evil design is accomplished.” According to Harry Seay, an advocate of designated saloon districts, wine rooms were also the cause of “more divorces on the grounds of infidelity than probably any other instrumentality.” In a lengthy 1906 letter to the Dallas City Council, reprinted in the Morning News, he said the wine room was the last stop on a slippery slope that began with a housewife sending to a saloon for drinks, then going herself, at first stopping at the door to collect her merchandise, but then coming inside and finally finding her way to the wine room. “Once there,” the Telegram chimed in, “ruin will surely follow!”

Wine rooms as trysting places were still common in Hell’s Half Acre in the years following the 1907 uproar. As long as they were confined to that sordid district, however, police tolerated them, as they did illegal gambling. The Acre was an unofficial “reservation,” where vice laws were suspended in the name of progressive law enforcement. But even that began to change in 1909 when the city moved to clean it up, first ordering saloons out of the district, then ordering out “lewd women.” While that dried up business in the Acre, beginning its long slide to irrelevance, there was plenty of vice still to be found in Fort Worth.

Elsewhere across the region wine rooms became the objects of muckraking exposés in big-city newspapers. The reports provided detailed descriptions of the establishments, such as Frank Goings’ saloon and wine room in Los Angeles, which operated on the ground floor of the “most prominent brick structure in the district,” with a hotel occupying the two floors above. Investigative reporters with the Los Angeles Herald described the entrance to the wine room through a side door “with a curtained glass upper sash.” Inside was a “sort of central aisle” with “curtained booths” on both sides, each furnished with “a table and seats.” Another doorway opened to the saloon, while a private stairway led up to the hotel. The reporters witnessed men entering booths with girls “still in their teens.” A waiter from the barroom brought rounds of drinks, with which the men plied the girls before enticing them upstairs. The reporters ended their account there, presumably to spare the tender sensibilities of their readers. The point was clear: Wine rooms branded saloons with the sin of fornication, contributing more to their unsavory reputation than all the drinking that went on at the bar.

Prohibition and ratification of the 18th Amendment in 1919 and the defiant flapper phenomenon of the 1920s finally put an end to wine rooms. The law closed all legal saloons for 14 years, and by the time they reopened in 1933, women were standing alongside men at the bar, a cigarette in one hand, a drink in the other. Today it seems hard to imagine men and women were once segregated in the pleasure palace known as the American saloon. WW

Richard Selcer of Fort Worth is a frequent contributor to Wild West. For further reading see his 2004 book Legendary Watering Holes: The Saloons that Made Texas Famous.