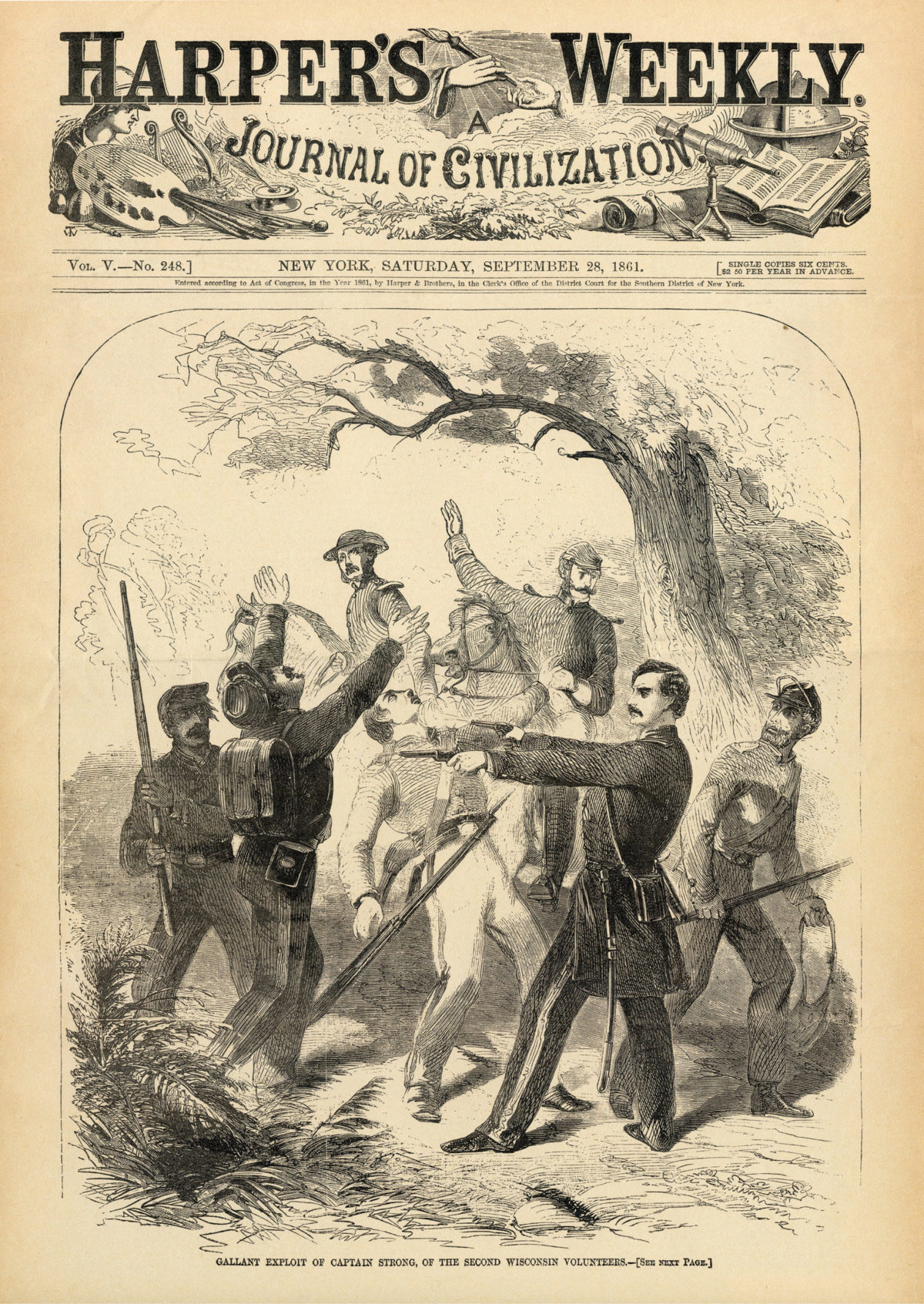

The First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, was a disaster for the North. The Northern public was hungry for heroes and eager for stories of individual courage and Union success. Wisconsin residents were understandably thrilled when the exploits of 2nd Wisconsin Captain William Strong made national news on the front page of the September 28, 1861, issue of Harper’s Weekly.

There, featured as the sole illustration on the cover, was the brave Union officer surrounded by six Confederate soldiers. The following article, “Gallant Exploit of Captain Strong, of the Second Wisconsin Volunteers,” described Strong’s reconnoitering of potential picket positions on September 6 along the Potomac River near Washington, D.C., and his sudden capture by the Rebels. The story recalled that when asked to surrender, 21-year-old Captain Strong, commander of Company F, shot two of his captors and ran to safety.

Strong shot the leader of the pursuing party but not before he was wounded and had several additional close calls with bullets passing through his clothing and canteen. Exhausted from his narrow escape and loss of blood, the captain was met by some of his pickets, who carried him back to camp. The story was picked up by Wisconsin newspapers, with the headline “Captain Strong’s Heroic Adventure” ensuring an even broader viewership of his exploits.

Shortly after the accounts were published, Major Charles H. Larrabee of the 5th Wisconsin Infantry, who commanded the picket line that day, documented Strong’s story for posterity in the archives of the State of Wisconsin. Writing to Mr. Lyman C. Draper, the corresponding secretary of the Wisconsin Historical Society, in his introduction to Captain Strong’s report, Major Larrabee stated:

“I was Officer of the Day at this time, and as such had charge of the line of pickets of this command. We had but two days before come over at a double to repel a supposed Rebel advance on Chain Bridge, and had been occupied day and night in throwing up earth-works to strengthen our position. The lines of the pickets had been stationed in the night of Tuesday, 3d September, and were in some cases in bad positions. I had just returned from a visit along the left exterior line—the centre being the turnpike from the Chain Bridge to Leesburg—and intended visiting the right exterior line. I called to Capt. Strong to accompany me but he not being quite ready—then awaiting his dinner—I having entire confidence in his discretion, directed him to make a careful examination of the picket stations, and especially of the right outpost, and be prepared to report to me when I should return from the examination of our exterior line, what alterations were in his judgment needed. Particularly I wished him to see whether our enemy could pass along the banks of the Potomac to the right of our pickets. On my return I found the Captain wounded—with all the marks of his encounter on him—but full of self-reliance and manly strength. Dr. Ward had passed me, and at this time was returning with him to camp. To show you how coolly he bore up under his exertions, upon offering him my horse, he absolutely refused, saying he was as sound as ever; so he went on to camp, some two miles, on foot.

“Col. Stannard, of the Vermont 3d Regiment, and myself then took a portion of the new guard, and some two hundred volunteers of the Wisconsin 2d, of the old guard, and scoured the woods where the affray took place….The next day I took two hundred men of the Indiana 19th, and thoroughly scoured the woods—found where horses had been picketed for some days past, and signs of the camp of pickets. We found the place of Strong’s encounter, and picked up what we supposed was a Secesh pistol, but we now find it was a small pocket pistol which Strong dropped in his retreat. I am thus minute because I really think this is the bravest and coolest act I recollect in our history.”

It is interesting to note that Major Larrabee had to order Captain Strong to record the incidents. Strong submitted this report that Larrabee forwarded to the Wisconsin Historical Society with the above cover letter:

Camp Advance, Sept. 7th, 1861

Major Larrabee: – Sir: In pursuance of your order of yesterday, I proceeded to examine the woods to the right of our exterior line, for the purpose of satisfying yourself whether the line should be extended. The last picket was stationed about four hundred yards from the river—being the outpost on our right exterior line—leaving a dense thicket of pine undergrowth between it and the river. From my means of observation up to that time, I had concluded that our pickets were not sufficiently advanced in that direction, as this space was wholly uncoupled. At least I thought the ground should be examined; and in this you were pleased fully to concur.

You desired me to make a minute examination of the ground, and to be ready to report when you should return, at 3 o’clock p.m. of that day. Accordingly after dinner I passed along the line until I reached the extreme outpost on the right—which consisted of Lieut. Dodge, Corporal Manderson, and three privates, and then proceeded alone over very rough and densely wooded ground to the river. I soon ascertained that these physical obstacles were so great, that no body of troops could, in this direction, turn our right flank, and there was no necessity of extending our pickets. I then concluded to return—and for the purpose of avoiding the dense under-growth, I turned back on a line about one hundred rods in advance of the direction of our line of pickets. As I was passing through a thicket, I was surrounded by six Rebel soldiers – four infantry and two cavalry. The footmen were poorly dressed, and badly armed, having old rusty altered muskets. The cavalry were well mounted and well armed. Seeing I was caught, I thought it best to surrender at once. So I said “Gentlemen, you have me.” I was asked various questions as to who I was, where I was going, what Regiment I belonged to, &c.—all of which I refused to answer. One of the footmen said, “Let’s hang the d—d Yankee scoundrel,” and pointed to a convenient limb. Another said, “No, let’s take him to camp and hang him there.” One of the cavalry, who seemed to be the leader, said “We will take him to camp.” Then they marched me through an open place—two footmen in front, two in the rear, and the cavalry man on each side of me. I was armed with two revolvers and my sword. After going some twenty rods, the Sergeant, who was on my right, noticing my pistols, commanded me to halt, and give them up, together with my sword. I said “Certainly, gentlemen,” and immediately halted. As I stopped, they all filed past me, and of course were in front. We were at this time in an open part of the woods, but about sixty yards to the rear was a thicket of under-growth. Thus everything was in my favor; I was quick of foot, and a passable shot. Yet the design of escape was not formed until I brought my pistol pouches to the front part of my body, and my hands touched the stocks. The grasping of the pistols suggested my cocking them as I drew them out. This I did, and the moment I got command of them, I shot down the two footmen nearest me—about six feet off—one with each hand. I immediately turned and ran towards the thicket in the rear. The confusion of my captors was apparently so great that I had nearly reached cover before shots were fired at me. One ball passed thought my left cheek—passing out of my mouth. Another one—a musket ball, went through my canteen. Immediately upon this volley, the two cavalry separated, one to my right, and another to my left, to cut off my retreat—the remaining two footmen charging directly towards me. I turned when the horse men got up and fired three or four shots; but the balls flew wild. I still ran on- got over a small knoll, and had nearly regained one of our pickets, when I was headed off by both of the mounted men. The Sergeant called to me to halt and surrender. I gave no reply, but fired at him, and ran in the opposite direction. He pursued and overtook me, and just as his horse’s head was abreast of me, I turned, took good aim, pulled the trigger, but the cap snapped. At this time his carbine was unslung, and he was holding it in both hands on the left side of his horse. He fired at my breast without raising the piece to his shoulder, and the shot passed from the right side of my coat, through it and my shirt to the left, just grazing the skin. The piece was so near as to burn the cloth out the size of one’s hand. I was, however, uninjured at this time save for the shot through my cheek. I then fired at him again, and brought him to the ground—hanging by his foot in the left stirrup, and his horse galloping towards his camp. I saw no more of the horseman on my left, nor the two footmen—but running on soon came to our own pickets—uninjured save the shot through the cheek, but otherwise much exhausted from my exertions.

Very Respectfully Yours,

Wm. E. Strong,

Captain Co. F., 2d R. W. V.

Strong was quickly promoted to major in part due to the media attention, and he returned to Wisconsin to help organize the 12th Wisconsin Infantry then being formed in Madison. Not all members of the 2nd Wisconsin, however, were convinced of the facts of the event, or how deserving he was of the subsequent fame.

Brevet Lt. Col. George H. Otis, who in 1861 was a newly promoted second lieutenant in Company I, stated after the war: “There were those that could scarcely credit the story, and I presume there are those living now who entertain doubts regarding the truthfulness of the captain’s story.” Lieutenant Colonel Lucius Fairchild commented in a September 22, 1861, letter to his sister: “Captain Strong has left us to be Major – He is a brave fellow, I suppose, & has made himself quite a name. I have been on the ground where it happened several times since – Day before yesterday I saw some rebels a long way off.” Even a year later, on September 8, 1862, Captain Wilson Colwell of Company B would write his wife, “the first one promoted was Capt. Strong and you know he got it through friends at home.”

So, what did actually happen on that day in September 1861, and were the comments by others valid or did it show their jealousy only at Captain Strong’s success? The newspapers had widely told the story of “Captain Strong’s Adventure” and noted that the report would be placed in the Wisconsin Historical Society for posterity. Several officers in the 2nd Wisconsin wrote and collected statements to document their own findings to supplement the historical record. For 161 years, those accounts remained in the archives, and are published here for the first time.

Second Lieutenant Nathaniel Rollins of Company H, one of the companies on picket duty that day, recounted how the geography called the events into question. He prefaced his evaluation of the terrain with:

“…Distrusting the truth of the story went and made a careful examination of the ground about the place stated to have been the scene of action by Capt. Strong. This survey was made last week in company with Lieut. [Dana] D. Dodge of Co. D of this Regt. I had previously been over the ground. I found these facts.”

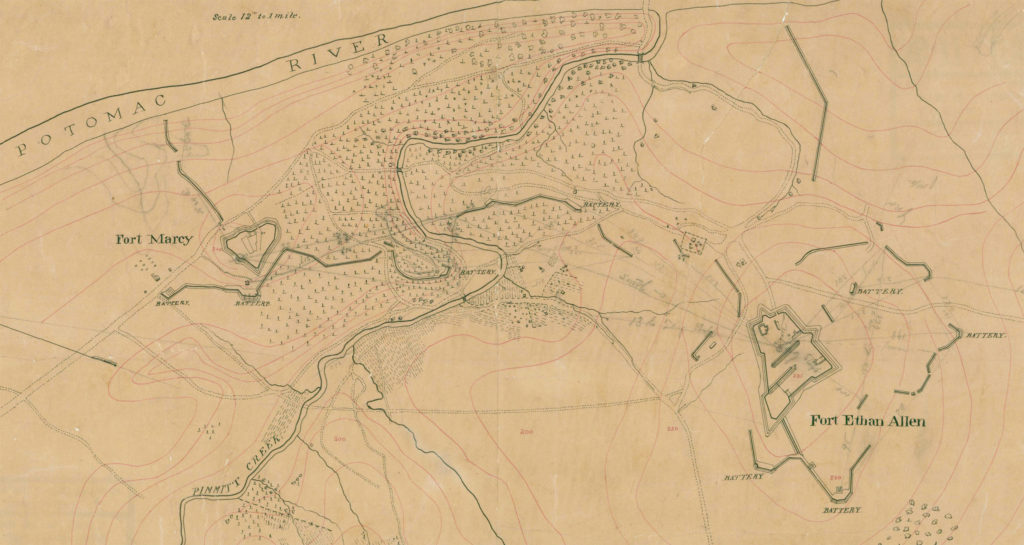

Rollins noted a high bluff along the river, making ascent there virtually impossible—that where Captain Strong indicated he was captured, “in either direction one goes down into a deep ravine, rocky and steep, the side of the hills are covered with a growth of scrub pine, oak, beech and hickory which grow very thick and generally covered with limbs from the ground to their tops.” As he and Lieutenant Dodge explored the area and attempted to move from the tree to more open ground they found that “ground of scrub pine was here so dense that several times we were obliged to retrace our steps and seek places offering less obstruction.”

Rollins next spoke to the placement of the picket line that overlooked the area in question. He noted that “All the ground…is in plain sight of the pickets posted on the open high ground east of the fence. It would be impossible for a horse to approach the large tree from the west across any of this ground without being in plain sight and within musket shot for the pickets.” The only area Rollins felt that horses could be brought through were in the areas of farmer Reid’s house and “the Negro hut” and each of those areas had “one to three fences full four feet high which show no signs of having been thrown down that I have ever seen and I visited the spot and examined the fences shortly after the reported exploit.” Due to the impassable terrain and the open line of sight of the pickets, it seemed impossible for the six Confederates to have gotten to the place Strong indicated that they had been. Lieutenant Dodge was 36 at the time and so was one of the older officers in the regiment. Dodge had been on the picket line that day and also related an account somewhat at odds with what Strong had reported:

“I was on picket guard and on Reid’s farm on the day that Capt. Wm E. Strong of the 2nd Wis. Vols. was reported or rather reported himself to have been shot by some rebel scouts. The Picket guard went out the day before the reported exploit….After the picket was posted Capt. Strong said he would meet me near Reid’s house at a certain guard post at 12 o’clock at night and again at 3:30 or 4 o’clock in the morning and would go with me along the line of pickets to see that all was right. I went to the appointed post at 12 and again at 3:30 where I waited until morning for Captain Strong when after day light I went up to the road to the reserve and there found Strong asleep and wakened him up. He said he had been there all night. That day at about one o’clock PM I was at the post near Reid’s house where I met Capt. Strong and he went down with me to the post nearest the river, marked on the sketch drawn by Adjt. Dean, where I stopped. Strong threw off his sword belt, pistols and coat at the fifth post from the last and then went over to the last post with me. He then said he would go back where he had left his things and lie down. About 1/2 or 3/4 of an hour afterwards, I heard the report of a pistol. The reports were all about alike. Sounded like pistol shots. Some of the privates with me remarked ‘there was some one shooting off his pistols.’

“There were certainly not to exceed ten or eleven shots in all. I shortly after went down the hill, back along the line of pickets, about to the fourth post from the last and there I found Capt. Strong. He said he had been shot by some rebels, that there were six rebels who had attacked him, four on foot and two mounted, that he (Strong) had killed one and wounded one, that he fired but four shots himself and that the other shots that I had heard were fired by the rebels. He then showed me the wound in his cheek, the holes in his canteen and coat. There was no blood on his face and I saw no signs of it having bled. I have seen quite a number of gun-shot wounds but this bore but very little resemblance to those I had seen. I remarked to Capt. Strong at the time that the wound could not have been made by a musket ball or by a carbine ball, that it could not have been more than a buckshot or a pistol. I noticed the hole in the canteen, the hole was too small for a musket or carbine ball and I then told him that must have been a pistol. The hole was very nearly through the center of the canteen. I thought it was very strange how the ball could go through the canteen in that way and not penetrate his body. I also noticed the shot hole in the coat. I noticed that the hole in the right side where he said the ball entered was lower than on the left side where it came out. The coat was badly scorched on the right side. This shot he said he had received from a man on horseback while he, Strong, was on the ground. He said the rebel put his carbine right against him [Strong] and fired! The cloth on the canteen was also scorched where the ball had entered. I proposed to him to let me take a squad of men, say two from each post near there, and go down in search of them but he positively objected, said it would not answer besides when he (Strong) called “rally” the rebels left as fast as they could run (I would here say I heard no one cry “rally” or anything else in that direction, yet the distance was so short and I was on higher ground that if anyone had cried for help I must have heard them). Capt. Strong then described minutely the place to me. I afterwards went (that afternoon) and examined the place but found no signs of the contest whatever. About ten days or two weeks after I was on picket again in the same place and again went over the ground and about thirty rods nearer the river and near the fence found Strong’s cap at the place as shown in the sketch. It is thick woods where the cap was found. I have been over the ground three different times, each time with different gentlemen and it is my candid opinion and the expressed opinion of all who have been there with me that it is impossible for cavalry to get to the fence mentioned by Strong as the scene of action. This statement is made without any feelings against Capt. Strong but merely that the public may know the real facts.”

Three enlisted men were then questioned. Albert F. Wade, First Sergeant, and Private Isaac R Higgins of Company D, and Private Frank Wilkins of Company H. Wade stated he was near Lieutenant Dodge on the picket line that day and went over the ground with him after the incident. He could see no indications of horses in the area and given the ground felt that the only way a horse could be at that spot was by the open ground near the brook or by going past “the negro’s hut.” Higgens heard the firing and noted they sounded all like pistol shots. He also looked over the ground and saw no disturbance and spoke of the ruggedness of the terrain and vegetation. Private Wilkens also went over the ground after the encounter and, while he saw some horse tracks, noted that farmer R.S. Reid had horses out at the time. He reiterated Wade’s comment that there were only two places, both open, that horses could be gotten to the spot. Captain George B. Ely of Company D also commented:

“That day I was in command of part of my Company on a working party at Fort Marcy. Just towards evening some one came up from our camp and said Capt. Strong had been shot by the Rebel Pickets and that the ambulance had been sent to bring him in. We soon went to camp & there found Lieut. Dodge who had also been on picket duty with part of my company and also Captain Strong. Strong’s face was bound up and he was standing by the cooking fire of his company which was near my company quarters and Major Allen and many others went to Strong to express our sympathy & hear an account of the affair. Strong talked freely and apparently without difficulty showed us his canteen shot through & through and the hole in his coat and gave his narration enthusiastically.”

After recounting the experience that Captain Strong also made in his report, Captain Ely then noted that he also saw Strong on the morning of the next day.

“The next morning he complained that his face was sore & he could not talk. He went that day to our old camp on Calarama [sic] Hill for the course of five or six days[,] he returned to the Regt. & resumed command of his company.”

Next to testify was R.S. Reid, the farmer who owned the property where the incident supposedly occurred. He noted he had resided on the land for over 50 years and was at home the day of the incident and the action would have taken place between his house and the river. Reid stated he saw no men that day other than the Federal picket and had never seen Confederates near his house. He also noted that the only way to get horses to the point Strong indicated was by going past his house and so “was fully convinced this was some mistake in statement” by Captain Strong.

Peter Arndt, the 2nd Wisconsin’s assistant surgeon, also provided his medical perspective on Strong’s wound.

“I hereby certify that Capt. Strong of Company F 2d Regt. Wis. Vol. presented himself to me for treatment of a wound of the cheek about 24 hours after such wound had been made or rec’d on the 7th day of September last. I found upon examination the wound penetrating through about the center of the left cheek, rather triangular in shape, the course was oblique pointing toward the right angle of the mouth and in its exit produced no wound of the lips or tongue….There was considerable tumefaction [swelling, Ed.] of the cheek at the time and I ordered an Elm poultice with muriate of ammonia dissolved, applied which in about 36 hours reduced the swelling when healthy suppuration took place and the wound healed very rapidly – There was no appearance of there having been much if any hemorrhage from the wound.

“The wound could not have been made by anything larger than a buck shot – There was no perceptible destruction of the parts and the wound was closed perfectly when I first saw it.”

Perhaps the most damaging statement of all is an account of a discussion Lieutenant Nathaniel Rollins and Charles K. Dean, the adjutant of the 2nd, had with Captain Charles Mundee, the assistant adjutant general of Brig. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith’s command. Rollins and Dean had wished to get a pass to investigate the area one more time, but orders now required approval from Smith to pass the main guard.

Dean “Capt.[,] Lieut. Rollins and I have a pass to go along the line of pickets which we wish you to approve.”

Mundee “I cannot do it Adjt. for Genl. McClellan has issued an order prohibiting any person’s passing beyond the main guard.”

Dean “We do not wish to go outside the pickets but only out, out to the place where Capt. Strong is reported to have had an encounter with some rebel scouts.”

Mundee “Why go now! You can’t take away his commission, you are too late.”

Dean “We have no wish to take away his commission, we had some doubts about the matter and wanted to satisfy ourselves.”

Mundee “Then it is unnecessary to go for the very next day after it was reported, we sent out and made a very thorough examination and satisfied ourselves full that nothing of the kind ever took place.”

Capt. Mundee afterward remarked that “there might possibly have been something but that he had seen so many such things, he put no confidence in the story from the first.”

On November 11, 1861, Charles K. Dean packaged up all the correspondence regarding the investigation along with his own recollections to send to Wisconsin. Dean closed his note by clarifying his intentions. He bore no malice nor ill feeling toward Captain Strong, nor was he jealous of his promotion. He noted that this was “the universal feeling of this Regt,” and finished the letter with the statement, “I have to request or enjoin that the papers in this case now furnished be filed with Capt Strong’s and Major Larrabee’s statements (now there) in the State Historical Society, and that in no case shall they be published.” And so it was for 161 years….

Marc Storch is the author of multiple articles and book chapters on the Iron Brigade. He and his wife are currently working on a history of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry. Kevin Hampton is the curator of history at the Wisconsin Veterans Museum and is researching the 7th Wisconsin Infantry.