The iconography of the Union crusade against slavery can be symbolized in a book, a song, and a photograph. The book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was read by hundreds of thousands; the song “John Brown’s Body,” was sung by tens of thousands of blue-coated emancipators; and the photograph was the hideously scarred back of a Black man known variously as Gordon, the whipped Peter, or merely the scarred slave. It’s the photograph and the story behind it that director Antoine Fuqua has taken as the subject of “Emancipation,” and he has harnessed the star power of Will Smith to depict the unrelenting cruelty of the South’s “peculiar institution.”

Slavery, like the Holocaust, is almost impossible to portray through any medium. But Fuqua and Smith have marshalled their considerable talents to produce a film that is hard to watch and impossible to look away from. The R rating is visible in nearly every celluloid frame. A brief summary of the real Gordon’s harrowing escape saga, given when he staggered into the encampment of several Massachusetts regiments of the Union’s 19th Corps outside Baton Rouge, La., in March 1863, will put the historical accuracy of William A. Collage’s sparse script to the test.

The historical Gordon escaped from the 3,000-acre cotton plantation of John Lyons, located along the west bank of the Atchafalaya River in St. Landry Parish, near today’s Krotz Springs, La. He spent 10 hellish days in the region’s swamps avoiding the relentless pursuit of blood hounds handled by the plantation’s overseer, Artayou Carrier. Gordon carried onions in his pockets to hide his scent from the pursuing dogs. New Orleans–based photographers William D. McPherson and his partner, Mr. Oliver, happened to be in the Union camp when Gordon stumbled in. They produced carte-de-visite photos of Gordon seated, stripped to the waist, his back showing the deep welts that crisscrossed his skin from his shoulders to his waist.

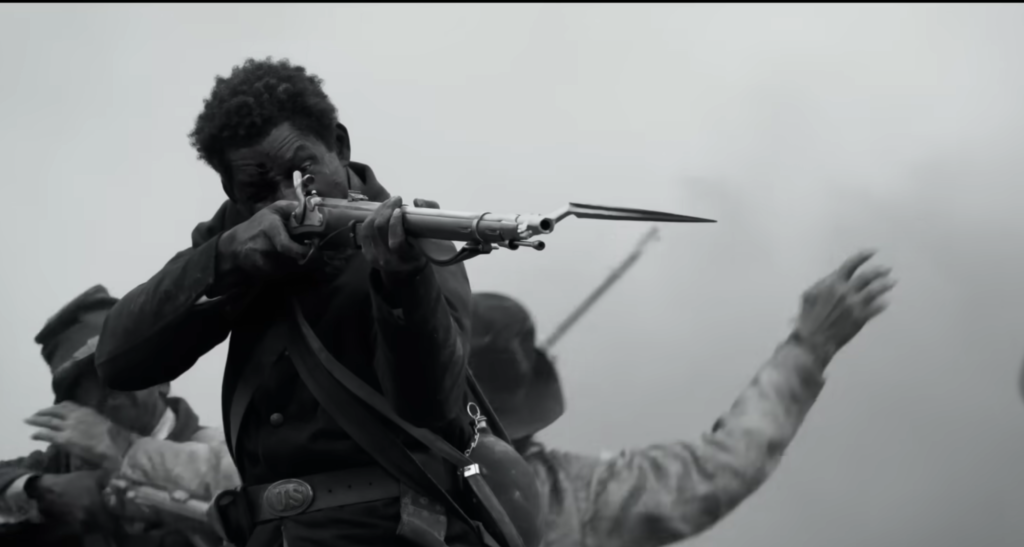

The photograph was reproduced by the thousands in the North and became an instant sensation. The photo appeared on the cover of Harper’s Weekly, the country’s most widely read journal during the Civil War. Gordon subsequently enlisted in the Louisiana Native Guards and fought at Port Hudson in July 1863. His life after the war is unknown.

Echoes of the Holocaust are unmistakable throughout the movie. In the film, Smith, playing Gordon, is torn from his wife, played by Charmaine Bingwa, and his children in a scene of random violence and thoughtless cruelty that will be repeated in many guises throughout the movie. Along with other slaves, Smith is herded into a prison-like cart and sent to labor alongside Confederate deserters rebuilding a railroad. Under concentration camp-like conditions, the worst of human nature becomes commonplace. Through senseless acts of sadism, men are worked like animals until they die and then their bodies are tossed into a mass grave.

The muted cinematography of Robert Richardson gives these scenes a documentary-like look—intended, probably, to symbolize the hopelessness forced upon slave laborers everywhere. “Where is God?” asks a dispirited slave. His answer, “He is nowhere,” is a reality Gordon cannot accept. It sparks his determination to escape from this environment of relentless evil and twisted humanity. Gordon’s inner strength comes from his determination to return and free his still enslaved family.

Smith portrays his 10 days on the run in the swamps with muted desperation and internalized rage. There is little dialogue and Smith’s physicality moves the action forward. Fuqua turns Louisiana into a Biblical wasteland through which Gordon must journey to find freedom and salvation. Smith faces and overcomes the worst forces of nature, including mud, snakes, and even alligators, as cruel and unrelenting as his life on the plantation.

In a sense, “Emancipation” is a story of redemption, and every redemption film needs an evil adversary that must be overcome. Smith finds his nemesis in Fassel, the overseer, portrayed with menacing determination by Ben Foster. “You walk the earth because I let you,” he snarls. Living under the capriciousness of someone having the power of life and death over another human being is the fate all enslaved must endure.

Fuqua’s film is without nuance, which denies him complete development of his characters. But “Emancipation” differs from other Hollywood efforts to portray slavery. There is no Lost Cause mythology, no redemptive whites to mitigate the worst aspects of the institution they have created and control. “Emancipation” is an unflinching exposure of an overwhelming corruption. But it is also an affirmation of the human spirit’s ability to overcome and survive. The film had a brief theatrical release and streams on Apple TV+ Starting December 9.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.