Editor’s note: This story was recognized by the Wild West History Association as "Best Article on Wild West History," July 13, 2013.

For a brief stint in 1869 James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok was sheriff of Ellis County, Kansas. A year later, in July 1870, Deputy U.S. Marshal Hickok revisited the bustling county seat, Hays City. He was drinking in one of the saloons when two troopers of Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer’s 7th U.S. Cavalry suddenly accosted him. In the ensuing struggle Hickok mortally wounded one soldier and severely injured another with a pistol shot to his knee. The cause of the brawl is unknown, though it was most likely triggered by a confrontation the wounded trooper had had with Hickok when Wild Bill was county sheriff. Hickok was lucky to escape the 1870 fight alive. The soldier who eventually died had reportedly pressed his Remington pistol to Wild Bill’s ear and pulled the trigger, only to have it misfire.

Contemporary newspaper accounts differed about how many soldiers were involved and exactly what happened. False accounts have since surfaced repeatedly in the growing Hickok literature, a biographer here and there embellishing the narrative, further submerging the truth in the miry bog of myth.

Some authors have suggested Wild Bill was wounded. In the first Hickok biography, published in 1880, J.W. Buel wrote that the fight involved 15 soldiers and began in Paddy Welch’s saloon on North Main Street, a few doors east of Tommy Drum’s saloon. According to Buel, a drunken sergeant challenged Wild Bill to a fight in the street. Hickok was easily winning when 14 of the sergeant’s comrades joined in and pummeled Wild Bill until the saloon owner handed the marshal his revolvers. Hickok killed one soldier, shot dead three more and mortally wounded two others. Hickok took seven wounds—three shots in his arms, three in the legs and a flesh wound in his side. Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan, claimed Buel, was so incensed that he ordered Wild Bill be brought to justice, dead or alive.

In all likelihood Hickok was not wounded in the saloon fight. Annie Gibson Roberts, who was visiting nearby Fort Hays at the time of the brawl, wrote in her diary of reports Wild Bill had been shot. Other than her diary entry, however, no contemporary accounts confirm his having been wounded. Indeed, within a week Hickok was again performing his duties as a deputy U.S. marshal, and in September he traveled to Abilene, Kansas, to arrest a counterfeiter.

Tracing the two soldiers’ lives has been a long process. No one had confirmed their actual names—Jeremiah Lonergan and John Kile—until Hickok biographer Joseph G. Rosa turned to military records almost 50 years ago in search of the truth surrounding the brawl. An accurate account of their military careers has remained hidden until now.

Most people writing about Hickok continued to use Buel’s embellished account until 1933 when biographer William Connelley changed the story and delivered the mythical coup de grace in Wild Bill and His Era: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok. In it Connelley asserted the greatest conceivable fiction as fact: The real perpetrator of the brawl was not a sergeant but rather Colonel Custer’s younger brother, a wild and drunken 1st Lt. Thomas Custer. According to Connelley, Tom liked to get drunk in Hays City when Hickok was serving as sheriff in 1869. On one such spree Tom ran his horse into a saloon. When he couldn’t get it to jump on the billiard table (something he had seen Hickok do with his own horse), Tom angrily shot his horse dead. Hickok arrested him. It was then, Connelley claimed, the brash lieutenant vowed revenge and enlisted three soldiers to kill the sheriff. While Wild Bill was drinking in a saloon on New Year’s Day 1870, one soldier jumped on his back and pinned his arms while another leaped upon him to hold him down. Hickok managed to free one of his six-shooters and fire behind him, instantly killing one soldier. He then shot and killed another soldier who’d taken aim at him. Finally, he fired over his shoulder again, killing the third soldier. Hickok then fled, knowing the entire 7th Cavalry would seek revenge.

Eugene Cunningham enshrined this fantastical Tom Custer connection in his classic 1941 book Triggernometry: A Gallery of Gunfighters. There was no longer any need to create new myths in the brawl. The legend had become fact—and it would mask the truth for decades. Connelley provided no documentation for the incredible tale in his book, but among his papers in the Western history collections of the Denver Public Library the author reveals that his account follows very closely a letter he received in 1925 from a Kansan named Rolla W. Coleman. But Coleman was not even born until seven years after the brawl, and he had waited until he was nearly 50 before sharing his account with Connelley. A weaker source could not be found. Further, if there were a grain of truth in this ridiculous account, one would find supporting documentation in the many surviving letters and accounts of the 7th Cavalry officers and enlisted men. George and Tom Custer had their detractors within the regiment, but not one of them hints at such a possibility.

The truth of the brawl began to unfold in 1964 when Rosa published They Called Him Wild Bill: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok. From untapped records in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., Rosa set straight exactly when the brawl happened—July 17, 1870—confirming the date in Annie Roberts’ diary, and established that only two troopers were shot, one fatally. This version is supported by the first publication to mention the brawl, W.E. Webb’s 1872 travelogue Buffalo Land.

When Rosa put out his second edition in 1974, he had learned a bit more, with the discovery of an obscure 1909 newspaper account of the brawl in The Newton (Mass.) Circuit by 7th Cavalry veteran John Ryan. Ryan had served 10 years in Custer’s cavalry and was the sergeant of Company M, to which the troopers involved in the brawl were assigned. Unlike others, Ryan really was there in 1870, and he knew both soldiers. He identified Jerry Lonergan as the soldier wounded. Ryan added interesting details about the soldier Hickok killed, noting the man had earlier deserted from Company M under the name John Kelley but upon reenlistment had gone by another name, which Ryan spelled as Kyle (a misspelling of the soldier’s real name, John Kile). Further, Ryan made clear the saloon in which the brawl happened was that of Tommy Drum, not Paddy Welch, as noted in Buel’s biography.

Ryan’s newspaper account was more fully fleshed out in his personal memoirs, which were lost for many years before being discovered in 2000 and edited and published by Sandy Barnard as Ten Years With Custer: A 7th Cavalryman’s Memoirs. In the memoirs Ryan claimed Lonergan and Hickok “had some trouble once before, which caused this action.”

From Ryan we learn that the troopers snuck into town from Camp Sturgis, near Fort Hays and across the river from Hays City, after the bugler had sounded tattoo. At their favorite haunt, Tommy Drum’s saloon, they became very drunk and no doubt boisterous, probably from two to four hours of merrymaking. Seeing Hickok standing at the bar, Lonergan threw himself upon the back of Wild Bill, quickly taking him down and holding him from behind to prevent the marshal from using his arms. But Lonergan couldn’t keep Hickok from pulling a revolver—Wild Bill had a reputation for placing his six-shooters backward in his belt for easy retrieval in cases just like this—and pointing it behind him. Kile, seeing Hickok gaining the advantage on his buddy, pulled his Remington pistol from his belt and put the barrel against Hickok’s ear. To Wild Bill’s fortune the gun misfired—Remingtons were notorious for misfires and, on occasion, blowing up—and before Kile could get off a second shot, Hickok pulled his trigger, striking Kile in the wrist. A second shot followed, piercing Kile through his stomach. With Kile mortally wounded, Wild Bill got off yet a third shot, this one striking Lonergan in the knee and thus freeing the marshal from the soldier’s grasp. With that, Hickok sprang to his feet and smashed through a window into the night, never again to appear in Hays City.

Had Kile’s revolver not misfired, few people today would know the name Wild Bill Hickok. Instead, the drunken Kansas brawl marked one of Hickok’s many violent encounters on his way to lasting fame as probably the most accurate, brave and lucky of the plainsmen who endure in the legacy of famous gunfighters.

Scholars and enthusiasts know the rest of Hickok’s life story, including his last moments at a card table in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, in August 1876. But a fuller picture of the two soldiers who participated in the Hays City brawl has only recently come to light via records in the National Archives.

Jeremiah Lonergan, born in Cork, Ireland, and 22 when he enlisted in New York City on December 26, 1867, again found himself in serious trouble just six months after his fight with Hickok. In a drunken rage after taps he repeatedly kicked at a sleeping corporal, yelling: “Get out of that bed, you Dutch son of a bitch, you bastard.…If I had a revolver, I would kill every Dutch son of a bitch in the quarters.” He then drew a knife and threatened the company first sergeant. In addition, according to his court-martial record, he did “with forethought and malicious intent, commit a nuisance in the quarters of his troop.” One soldier testified that Lonergan threatened, “He would s___ in the room [barracks] if he had a mind to, and nobody would say a word to him.” Indeed, continued the soldier, “He [Lonergan] stopped and done his business in the quarters, [making] a deposit of man manure on the floor.”

When 1st Sgt. Frederick Thies told Lonergan he was going to the guardhouse, the quick-tempered soldier replied, “Before I go to the guardhouse, I shall give you some more trouble.” Thies quickly put on his belt and pistol and then ordered him to the guardhouse. Lonergan drew a clasp knife from his pocket, opened it and threatened, “If you say another word to me, I’ll cut the guts out of you.” The sergeant then drew his pistol, subduing Lonergan.

Convicted by court-martial, Lonergan was sentenced to nearly three years at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas—the rest of his initial five-year enlistment—and then given a dishonorable discharge. While in prison he sought to have his sentence commuted. His poorly spelled request reads: “I hereby ask for a remission of sentence and to be again restored to duty, if such is possible, having bin in the U.S. service since ’61 and endured all the hard ships of a soldier’s life during the late rebellion, suffered the hard ships of Southern prison as a prisoner of war for eight months. Upon being discharged, I again joined the Regular Army and have served honorably ever since, until the misfortune of being court-martialed befell me. I have no disliken to become a soldier again, having never deserted the Army. I feel my self capable of doing the duty of a soldier in every respect.”

Superiors turned down Lonergan’s request with this comment: “He is probably a coarse blackguard, when sober, yet the record makes it apparent that the words and acts for which he was tried and sentenced were the result of intoxication. His threats were the boasts of a drunken man.” The service wanted nothing more to do with him, and after being sentenced, he disappeared from history. Ryan’s memoirs erroneously reported that Lonergan deserted and was later killed by an infantryman during another drunken brawl at another saloon somewhere in Kansas.

![]()

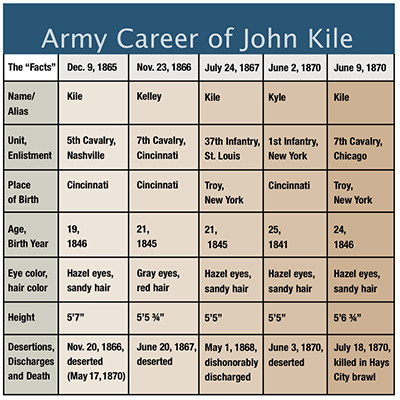

John Kile’s military career was more complex—marked by desertions, courts-martial, prison sentences, heroic actions and manipulations of the military system (see chart). Kile first enlisted as a teenager in the 5th Cavalry on December 9, 1865. On November 20, 1866, he deserted. Three days later he reenlisted as John Kelley into the 7th Cavalry, serving

John Kile’s military career was more complex—marked by desertions, courts-martial, prison sentences, heroic actions and manipulations of the military system (see chart). Kile first enlisted as a teenager in the 5th Cavalry on December 9, 1865. On November 20, 1866, he deserted. Three days later he reenlisted as John Kelley into the 7th Cavalry, serving ![]() in Company M with John Ryan. On June 20, 1867, he deserted the 7th Cavalry—surprisingly, with Ryan, who omitted the incident from his memoirs. On July 24 he reenlisted as John Kile into the 37th Infantry. On May 1, 1868, he was court-martialed and given a dishonorable discharge as well as a three-year prison sentence, from which he escaped. He then turned himself in on August 19, 1868, to face a court-martial for his earlier 5th Cavalry desertion. He was sentenced to eight months of hard labor. After finishing in May 1869, he participated in the 5th Cavalry Republican River Expedition.

in Company M with John Ryan. On June 20, 1867, he deserted the 7th Cavalry—surprisingly, with Ryan, who omitted the incident from his memoirs. On July 24 he reenlisted as John Kile into the 37th Infantry. On May 1, 1868, he was court-martialed and given a dishonorable discharge as well as a three-year prison sentence, from which he escaped. He then turned himself in on August 19, 1868, to face a court-martial for his earlier 5th Cavalry desertion. He was sentenced to eight months of hard labor. After finishing in May 1869, he participated in the 5th Cavalry Republican River Expedition.

On July 8, 1869, he had a fight with Indians, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor, receiving it on August 24 but with his name given as “Kyle.” The misspelling came from Lieutenant William Volkmar’s itinerary report that Brevet Maj. Gen. Eugene A. Carr used to write the MOH recommendation. On May 17, 1870, Kile finished his 5th Cavalry enlistment as a first sergeant, a soldier described as having good character. Two weeks later he reenlisted—using the misspelled name John Kyle—into the 1st Infantry in Buffalo, N.Y. But he deserted the next day and then reenlisted one last time, back in the 7th Cavalry, on June 9, as John Kile. He reported for duty at Fort Hays on June 26 and just three weeks later had his fatal brawl with Hickok. Even this short version of Kile’s career is confusing and begs for further elaboration.

Kile’s early service with the 5th Cavalry dealt with the Federal occupation of the Southern states at the close of the Civil War. In late fall 1866 he was part of a detail that escorted citizen prisoners, guerrillas, etc., from Mitchellville, Tenn. (north of Nashville), to Louisville, Ky. Kile rode the train north and delivered the prisoners, but on November 20 he missed the return train from Louisville (he was probably drinking) and was charged with desertion. Three days later he enlisted in the 7th Cavalry under the alias John Kelley. He was soon promoted to corporal of Company M and in the summer of 1867 participated in George Custer’s Hancock Expedition as well as Custer’s first independent Indian campaign (see “Custer’s First Fight With Plains Indians,” by Jeff Broome, in the June 2007 Wild West). He again deserted when Custer’s command was in Nebraska. The military records vary as to the exact date he disappeared, but in all likelihood he was discovered missing on the morning of June 20. He then reenlisted a month later as John Kile in the 37th Infantry.

Because of Kile’s 1866-67 7th Cavalry stint as John Kelley, he was immediately recognized as a deserter when he returned to the regiment in 1870 (more on what happened in between later). Ryan’s memoirs recount what happened next, but they do not mention Ryan’s desertion with Kelley/Kile. In fact, superiors had exonerated Ryan from his 1867 desertion, buying his argument that while going to retrieve water for several canteens at a stream not far from Custer’s Fort McPherson command, he had become hopelessly lost in a dense fog. (He’d turned himself in two months after disappearing.) That same alibi would now work for Kelley/Kile, since he and Ryan both were corporals when they deserted together.

Ryan wrote that upon his friend’s return in 1870, he took Kelley/Kile to Custer. “General,” Ryan told Custer, “I have brought a man to you by the name of Kelley. He has surrendered to me as a deserter.” Ryan recalled: “The general asked me what company he deserted from, and I told him Co. M.…He also asked me what kind of man he was, and I told him that he was a very good soldier and a corporal in my company.…During the time that Kelley had been away from the 7th Cavalry, he enlisted in the 5th U.S. Cavalry and served under General [Eugene] Carr over in the Department of the Platte and had some meritorious papers from that general.” Custer replied, “Well, Sergeant Ryan, you take him back and report him to the 1st sergeant of his company for duty.” Not sure which company to take him to, Ryan said to Custer, “Kelley deserted from Co. M, my company, and he was now assigned to Co. I.” Custer, according to Ryan, then told him to take Kelley “back to the 1st sergeant of Co. M and turn him over for duty.”

National Archives records confirm that Kelley/Kile was actually the same person, a question that had troubled Rosa and other writers. When Kile was killed, the company commander filled out a standard form explaining the cause of death. Captain Myles Keogh, commander of Company I, filled out that form: “Death of pistol shot received July 17, 1870, at Hays City, Kansas. Died in post hospital at Fort Hays, Kans, July 18, 1870.” Headquarters sent back Keogh’s statement, as he had failed to indicate whether the death was in the line of duty. Keogh amended the form, explaining that Kile died “at Fort Hays, Kans. (in post hospital), by reason of pistol ball wound received July 17, 1870, in a drunken row at Hays City, Kans., and not in the line of duty. Private Kile (alias Kelley) was originally a deserter of Troop M of this regiment and on reenlisting was assigned to Troop I but attached and doing duty with Troop M at the time he was killed.” The form provided another clue about Kile when Keogh added: “Last served in Co. M, 5th U.S. Cavalry. Discharged May 17, 1870.” The 5th Cavalry muster rolls confirm this soldier enlisted December 9, 1865, and deserted November 20, 1866.

After his 1867 desertion from Custer’s command, Kelley/Kile enlisted in the 37th Infantry—as John Kile—where things took a downturn. He was assigned to Company C and sent to northern New Mexico Territory, where his company was to construct a new camp, later named Fort Lowell. On Christmas Day 1867 Kile was arrested for being drunk and, worse yet, accused with two other soldiers of breaking into the sutler’s store and taking more than $600 in merchandise, including clothes and boots. Kile was found guilty of all charges, sentenced to a dishonorable discharge and ordered to serve three years in the federal prison in Jefferson City, Mo.

Though records are unclear exactly how Kile avoided his sentence in Jefferson City, he certainly did. Penitentiary records show he was never admitted. Since Fort Lowell was literally in the middle of nowhere, it was a few weeks before an escort could take him from New Mexico Territory to Missouri. The Company C, 37th Infantry muster roll for June 1868 states that Lieutenant [John W.] Jordan was removed from command of his company for leaving “the company in charge of prisoners.” It can be surmised that Kile escaped from his escort.

Kile next appeared before military authorities in Gallatin, Tenn., where he voluntarily surrendered for his November 20, 1866, desertion from the 5th Cavalry, his initial enlistment into the Army. At this second court-martial for his first desertion, he pled guilty and asked for consideration from the court in sentencing, noting that his “intentions were not bad” when he deserted. Kile gave an interesting statement regarding why he deserted:

"When I went to Louisville, I turned over the prisoners and went up in town and expected to be back in time for the train in company with some of the men of the detachment. I did not mean to stay but stayed until after the train left and the detachment went away. I stayed a considerable time over my time, and was afraid to come back on account of punishment, and thought Captain [Edward H.] Leib was down on me, as a few days previous to that he had threatened to have me driven out of the company. That was one reason I did not come back. Afterward I was sorry for what I had done, and seen [sic] that I was wrong, and came back and reported. I hope the court will be just enough to give me a just and fair trial, as my intentions were not bad when I left."

By May 1869 he was back serving in his company and soon promoted to corporal. Carr’s Republican River Expedition engaged in several fights with the hostile Cheyenne Dog Soldiers under the leadership of Tall Bull, and Kile distinguished himself in each one. In one skirmish he fought alongside 23-year-old scout Buffalo Bill Cody. The Indians, smarting from their losses, went into north-central Kansas and conducted a series of retaliatory raids against outlying settlements and stage stations, killing several settlers and capturing two women (see “Death at Summit Springs: Susanna Alderdice and the Cheyennes,” by Jeff Broome, in the October 2003 Wild West).

Shortly after the women’s capture, Carr again went in pursuit of the Indians. In early July, as Carr moved from Nebraska into Colorado Territory, he sent nearly half of his command under Brevet Major William Bedford Royall to follow one trail west, roughly along the Republican River, while he stayed with the rest of his command and crossed the Republican in a southwest direction following the Arikaree River. Royall’s command, including Kile’s Company M, had a brisk skirmish with a few warriors, killing three. Running out of rations, Royall rejoined Carr. When the two forces came together on July 7, Carr withdrew the command to a campsite very close to where the 1868 Battle of Beecher Island had been fought.

The next day Corporal Kile and two privates volunteered to retrieve a horse Royall had abandoned. They found the horse and were returning to camp when a dozen Dog Soldiers charged into them. Lieutenant Volkmar wrote that the men “were attacked by a much superior force of Indians, of whom they killed and wounded three and made their escape.”

Carr reported that the soldiers killed the lame horse for defense and repelled the Indians. “Corporal John Kyle [Kile], Company M, 5th Cavalry, was in charge of the party; he showed especial bravery on this, as he had done on previous occasions.” Another officer with Carr, George Price, later wrote that Kyle/Kile “had a brilliant affair at Dog Creek,” in which the Indians—13 of them—surrounded the small party but soon lost three killed and departed.

The biggest fight in Carr’s expedition, however, happened three days later at Summit Springs in northeast Colorado Territory—among the most significant and underrated battles of the entire Indian wars era. There, in the early afternoon of July 11, 1869, Carr’s command surprised an unsuspecting Cheyenne village of 84 lodges. When the 5th Cavalry—Kile and Cody included—charged in with a contingent of Pawnee Indian scouts, they routed the village. Though most of the nearly 500 Cheyennes escaped, the troopers and scouts killed anywhere from 52 to 73 Dog Soldiers, including Chief Tall Bull. Only one soldier was wounded. A warrior killed captive Susanna Alderdice when the fight began. Captive Maria Weichel was shot in the back but recovered.

Kile was discharged on May 17, 1870, his enlistment having expired. Within two weeks he surfaced in Buffalo, N.Y., and reenlisted on June 2 in the 1st Infantry. In Kile’s era, when a soldier reenlisted within 30 days after finishing an earlier enlistment, he would receive an additional $2 per month in pay throughout the reenlistment. Another $2 was given to anyone issued a Certificate of Merit, an official recognition of acts of bravery short of receiving the Medal of Honor. Kile’s MOH papers more than qualified him for the extra $2 per month.

But he enlisted as John Kyle, rather than under his real name of Kile, and within a day deserted. He then went to Chicago and on June 9 re-enlisted yet again, this time back into the 7th Cavalry, as John Kile. Information written on both enlistment papers verifies his earlier enlistment with the 5th Cavalry, proving that Kyle/Kile was the same man.

Why did Kile use the name Kyle when he enlisted in New York, and why did he immediately desert? Army regulations at the time mandated no large bonuses for reenlistment, so that cannot be the reason.

Kile’s use of the name Kyle was probably to avoid detection, as Kile had a 37th Infantry bad conduct discharge and had escaped a prison sentence. If he enlisted under his real name, the records could potentially catch up to him, and if caught, he faced years behind bars and the end of his military career. Kile may have deserted so quickly because he recognized an officer who would remember him from New Mexico Territory. The prospect of arrest would have convinced him to desert. Desertion had served his needs in the past, so why not again?

Kile obviously wanted a military career and apparently loved Army life. Thus he reenlisted one week later, hoping to continue his chosen career. He avoided the infantry and instead enlisted back into the cavalry as John Kile, the only name he could use and remain eligible for the monthly reenlistment and Medal of Honor bonuses, since he had just deserted under the name Kyle. But, as destiny proclaimed, he was assigned back to the 7th Cavalry. It was fortuitous that John Ryan recognized him almost upon arrival, for it was then very easy for George Custer, given Ryan’s testimony, to exonerate Kile (Kelley) for his 1867 desertion. Kile’s 5th Cavalry papers revealing both the coveted Medal of Honor and his former rank of first sergeant was gravy on the meat. Custer had every reason to believe Kile was a meritorious soldier and would perform well back in his regiment. Kile no doubt felt likewise.

The deadly Hays City brawl on July 17, 1870, finally brought an end to John Kile’s long string of desertions and reenlistments. Events seemed to have played out that night the way they often did in frontier saloons when men drank too much. Lonergan and Kile annoyed the wrong man, one who knew how to use a six-shooter better than almost anyone and who was fully prepared to defend himself. Kile’s killer, Wild Bill Hickok, went on to an equally violent demise six years later in Deadwood—fatally shot from behind by drifter Jack McCall on August 2, 1876. That June, of course, George and Tom Custer, Keogh and many other 7th Cavalry officers died at the Little Bighorn.

One can only wonder what history would reflect had Kile’s service revolver not misfired that night he brawled with a frontier legend. Certainly Kile would be much better remembered today—as the Medal of Honor recipient who killed Wild Bill Hickok. Instead, Kile died at 24. Today Kile’s remains are interred at the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery. His headstone bears the insignia and gold trim of an MOH recipient and, after more than 130 years, his real name. He at least deserves that.

Jeff Broome of Colorado is writing a book about Hickok and the 1870 Hays City brawl. Also see They Called Him Wild Bill and Wild Bill Hickok, Gunfighter, both by Joseph G. Rosa.