ON JULY 6, 1944, Jack R. “Jackie” Robinson, a 25-year-old African American lieutenant with the 761st Tank Battalion, boarded a shuttle bus in front of the Black officers’ club at Camp Hood, Texas, and took a seat halfway down the aisle. Five stops later, the civilian driver ordered him to the back of the bus, as was the custom in states that enforced racial segregation. Robinson refused to move; he was on a U.S. Army base and saw no reason why he couldn’t sit where he wanted. When Robinson didn’t budge, the driver promised to make trouble once the bus reached its destination.

Recommended for you

He was true to his word. Aided by irate civilians and later by officious army officers, the driver made plenty of trouble for the young lieutenant, as Robinson’s stand against discrimination spiraled into a cause célèbre that threatened his army career. It also jeopardized a future place in history that no Black athlete of his day would have dared dream of.

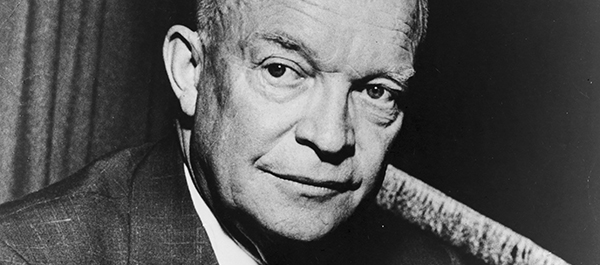

FROM ATHLETE TO ARMY LIEUTENANT

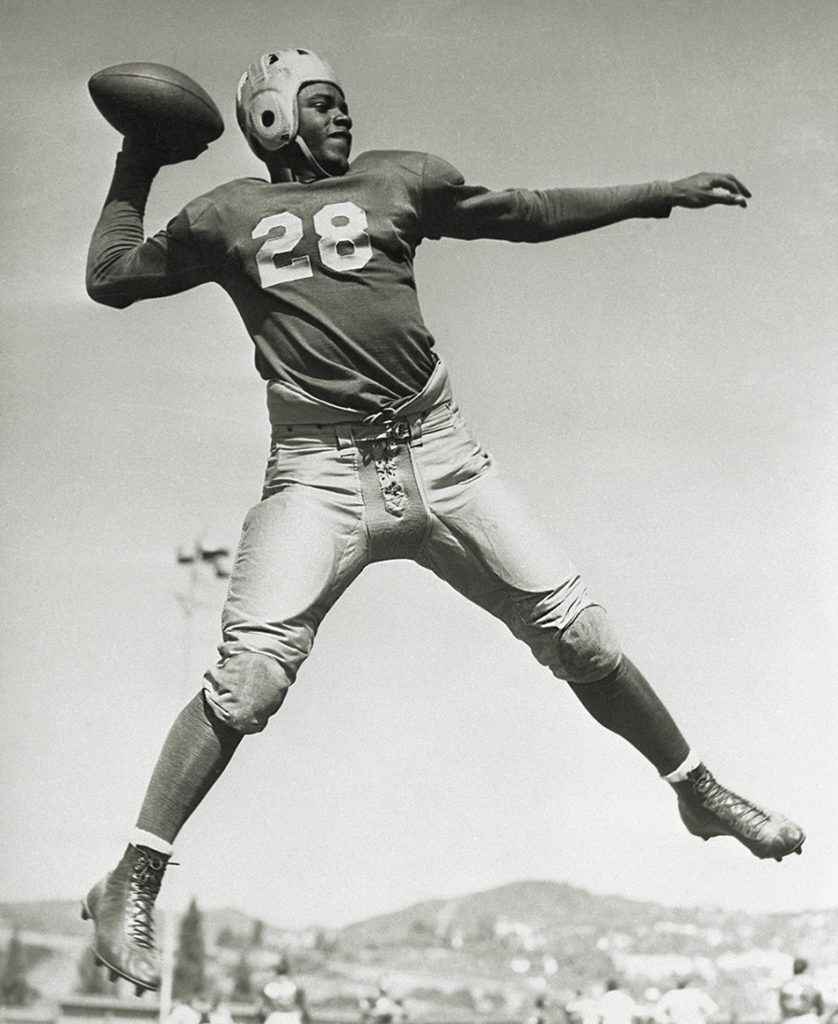

Robinson was familiar with racism. Born in 1919 and raised in a predominantly White neighborhood in Pasadena, California, he had endured insults and racial slurs from his neighbors. Standing 5 foot 11 and weighing 180 pounds, he blossomed into a standout athlete at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), lettering in football, baseball, basketball, and track. On the gridiron, he won nationwide fame as a running back and punt returner, earning favorable comparisons to Jim Thorpe, the Olympic gold medalist, professional football player, and major league baseball player widely acknowledged at the time as America’s finest all-around athlete. After Robinson left UCLA in 1941, the next stop should have been the National Football League, but the league barred African Americans, so Robinson played minor league football with the integrated Honolulu Bears and Los Angeles Bulldogs until he was drafted into the army on April 3, 1942.

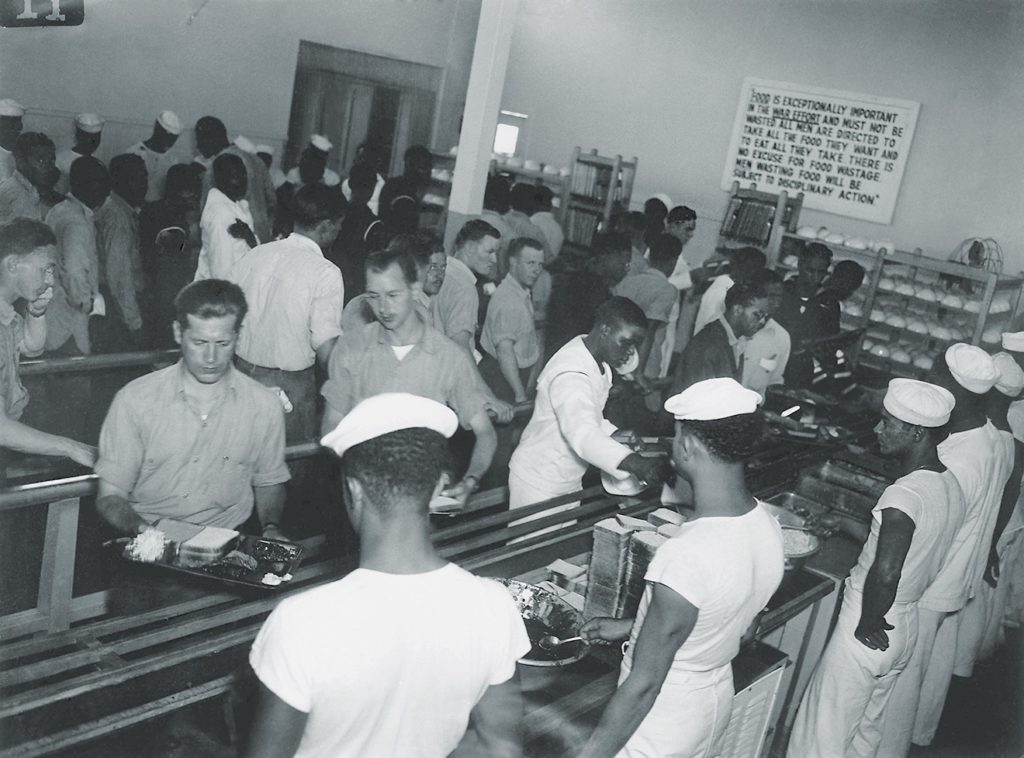

The military that Robinson entered was expanding rapidly to fight an all-out war, jumping from 334,473 men and women in 1939 to 3.9 million in 1942 and peaking at 12.2 million in 1945. One of the challenges facing the armed forces was the role of African Americans. Black men had fought in every war since the Revolution, but the armed services didn’t treat them the same as White men, and segregation was the rule.

In December 1941, the army had 99,206 Black soldiers serving in segregated units commanded by White field-grade officers. The navy had 5,026 African-American sailors, but until April 1942, Black enlistees weren’t allowed any role other than as messmen serving meals, shining shoes, and making beds for White officers. The Marine Corps had no Black members; it wouldn’t begin accepting African Americans until June 1942. On military bases, post exchanges (PXs) and service clubs were often segregated. Even the American Red Cross, which collected blood for the military, kept Black and White blood donations separate so, it assured the public, “those receiving transfusions may be given plasma from blood of their own race.”

The Selective Service Act of 1940 forbade discrimination based on race; additionally, a 1941 executive order from President Franklin D. Roosevelt prohibited government agencies from racial discrimination. However, since 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court had held that segregation wasn’t discrimination, so the military’s practices passed legal muster.

Civil rights leaders pushed for integration, but the armed services dug in their heels. In September 1940, the War Department insisted that segregation in the military “has been proven satisfactory over a long period of years” and that any attempt to force integration “would produce situations destructive to morale and detrimental to the preparations for national defense.” A War Department official told African American newspaper publishers and editors in 1941 that “the Army is not a sociological laboratory.” Expediency was used to justify this stance: in December 1941, Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall contended that the “settlement of vexing racial problems cannot be permitted to complicate the tremendous task of the War Department.” Integration of the armed services would have to await the end of the war.

Soldiers’ views broke down according to race. A 1943 army survey showed that nearly 90 percent of White respondents favored segregated units and service clubs, but fewer than 40 percent of African American soldiers agreed.

Off base, local laws governed. These laws varied from state to state, but in the South, they often mandated strict racial separation. The experience of soldiers being shipped through El Paso, Texas, in 1944 showed the farcical way these edicts often played out. Black G.I.s, not allowed to enter a restaurant near the train depot, sat outside eating “cold handouts,” Time magazine reported, while they watched German prisoners inside enjoying a hot meal. Segregationist regulations were called “Jim Crow,” named for a 19th-century minstrel show character that depicted African Americans in a demeaning way.

A flashpoint for racial tension was bus service at military bases. Soldiers, both Black and White, relied on buses, usually operated by civilian companies. Shuttles transported soldiers inside sprawling bases, and buses were necessary to travel to the nearest towns, often miles from camp. Civilians working on military bases also rode these buses. In areas where Jim Crow ruled, Black soldiers were relegated to the back of the bus, even on army bases.

“The South,” Time reported, was “prepared to back up its Jim Crow laws with force.” On July 28, 1942, in Beaumont, Texas, police officers beat and shot Private Charles J. Reco for refusing to leave his seat in the White section of a bus. On March 13, 1944, a driver in Alexandria, Louisiana, shot and killed Private Edward Green for failing to move to the back of the bus.

Violence may have been isolated, but the indignities weren’t. In 1943, the Reverend James L. Horace, an African American minister from Chicago, conducted his own investigation, riding the buses on and near nine southern military bases. He found the treatment of Black soldiers to be abysmal. At Fort Benning, Georgia, for example, drivers sometimes refused to pick up African American G.I.s, and at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, surly bus drivers “seem to have been urged by the enemy to destroy Negro morale,” Horace wrote. Reporter Orrin C. Evans told of an African American sergeant who said he avoided buses at all costs because he didn’t want to “get my head whipped” by a racist driver. Even the military police (MPs) got involved, arresting Sergeant Joe Louis, the world heavyweight boxing champion, on March 22, 1944, near Camp Sibert, Alabama, for entering a bus depot’s Whites-only section to make a phone call.

Standing strong

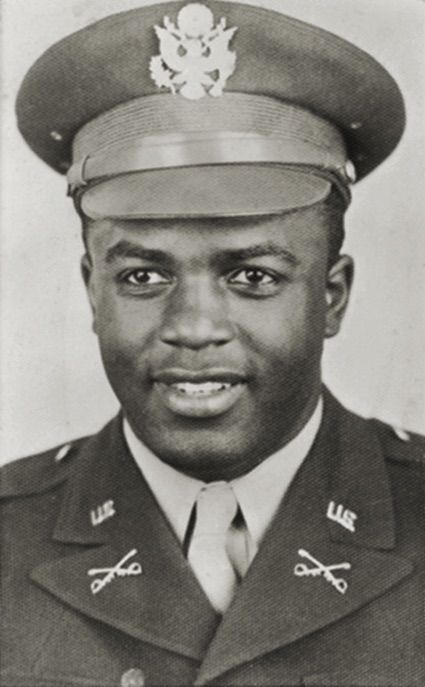

DESPITE THE MILITARY’S racial policies, Jackie Robinson adapted well to the army. He was selected for Officer Candidate School and commissioned on January 28, 1943. In April 1944, he was assigned to Camp Hood, Texas, and the all-Black 761st Tank Battalion, an outfit that called itself the “Black Panthers.” As a platoon leader, Robinson quickly earned the respect of his men and the admiration of his 36-year-old White battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Paul L. Bates.

The 761st was being groomed for combat in Europe, but it wasn’t a sure thing that Robinson would go overseas. In 1937, he had broken his right ankle playing football. The injury had not healed properly, and Robinson had aggravated it on an army obstacle course in 1943. He had bone chips in the ankle, causing pain and swelling. In January 1944, an army medical board had found him fit only for limited duty and recommended against strenuous use of his right leg. He was ordered to McCloskey General Hospital in Temple, Texas, on June 21, 1944, for a final decision on his fitness for combat.

On July 6, while still being assessed at the hospital, Robinson traveled to Camp Hood to visit friends at the Black officers’ club. A teetotaler, he arrived at 7:30 p.m. and left at 10 p.m., planning to take a bus to the base’s central station and then hop on another for the 30-mile trip back to the hospital.

Robinson boarded a shuttle driven by a civilian, Milton Renegar, at Stop No. 23. Robinson saw a familiar face and sat next to her in the midsection of the bus. She was Virginia Jones, the wife of another Black officer in the 761st and a woman Robinson described as “very fair” and often mistaken for White. Five stops later, at Stop No. 18, Renegar ordered Robinson to the back of the bus. Renegar expected White women to board at the following stops, he said later, and didn’t think they’d want to sit near a Black man. Texas law required African Americans to sit in the back, but Robinson refused to move. He grudgingly obeyed Jim Crow rules while off post, he said, but not on an army base. When Robinson stayed in his seat, Renegar vowed that Robinson would pay for his defiance when they reached the depot.

After the bus arrived at the station, passenger Elizabeth Poitevint scolded Robinson.

“Well, listen buddy, you ought to know where you should sit on a bus,” she told him. She worked at a Camp Hood PX and had no love for Black soldiers, later telling investigators, “I had to wait on them during the day, but I didn’t have to sit with them on the bus.” Renegar demanded to see Robinson’s army identification card so he could report him, but Robinson refused to show it. As tempers flared, bystanders gathered, and Renegar told them, “this n—-r is making trouble.” Robinson warned Renegar to “stop f—in’ with me,” and Bevlia B. Younger, the depot dispatcher, called the MPs.

MP Corporal George A. Elwood arrived at about 10:20 p.m. Younger told him “a n—-r lieutenant” was causing trouble, and another bystander demanded Elwood do something since Whites had been “cussed out by a n—-r.” The situation was volatile, and Elwood decided to take Robinson to the camp’s MP guard room to sort things out. Robinson was willing to go because he was confident he could show he had acted well within his rights. As Robinson sat in Elwood’s patrol car, Private Ben W. Muckelrath, a 27-year-old witness to the exchanges, asked Elwood if he had “that n—-r lieutenant” in his car. Robinson heard him and erupted, “I’m an officer and God damn you, you better address me as one.” Elwood drove Robinson and Muckelrath to the guard room, and the other witnesses followed later.

At the guard room, MP Sergeant William L. Painter asked what had happened, and Muckelrath gave an account that portrayed Robinson as profane and out of control at the depot. “That’s not so,” Robinson said, and he warned Muckelrath that if he ever called him “n—-r” again, he’d break him in two.

Painter summoned the officer of the day, Captain Peelor L. Wigginton. Robinson told Wigginton how offensive Muckelrath’s racial slur was: “Captain, any private, you, or any general, calls me a n—-r, and I’ll break him in two.” Muckelrath denied using the term, and Wigginton seemed to believe him. Wigginton called in Captain Gerald M. Bear, the assistant provost marshal.

When Bear arrived, Robinson followed him into the guard room, anxious to tell his side of the story, but Bear told him to stay out. “Nobody comes in the room until I tell him,” Bear said. Muckelrath was already in the room and allowed to stay, and Bear seemed to want his account, not Robinson’s. Robinson went into the receiving room, which was separated from the guard room by an open door, and stood by the door. Several times, he interrupted Muckelrath to “get him to correct his statement.” Bear ordered Robinson to sit in a chair on the far end of the receiving room, away from the door, so that he couldn’t interrupt. Robinson responded, Bear claimed, by bowing, saluting sloppily, and saying, “O.K., Sir” in a sarcastic tone.

Bear walked to the building next door to call for a stenographer to take statements from Robinson and the witnesses. When Bear returned, Robinson was outside the building chatting with another soldier. Bear saw this as disobedience of his order to stay in the receiving room. It was an odd position to take because Bear later admitted his order was designed only to keep Robinson out of hearing range of the conversations inside the guard room, and standing outside the building certainly accomplished that. Nevertheless, Bear took offense and ordered Robinson back into the receiving room. Bear’s demeanor alarmed Robinson. Throughout the encounter, Robinson later testified, Bear acted “very uncivil toward me; and he did not seem to recognize me as an officer at all.”

A stenographer, Mrs. Wilson, arrived at the guard room and took Robinson’s statement. After she had transcribed it, Robinson said, she and Bear became angry when he pointed out errors in the document. Bear, however, said the issue wasn’t with Mrs. Wilson but with Robinson’s conduct while the statement was being taken. After Bear had told Robinson to slow down so the stenographer could record all his words, Robinson had spoken in an unusually slow and mocking manner, Bear claimed. Bear had several MPs escort Robinson back to the hospital in an army truck.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL BATES, Robinson’s battalion commander, tried to protect the young lieutenant. Known for his loyalty to his men, Bates had recently declined a promotion because it would have meant leaving the 761st. Bates sent Robinson home to California on leave, hoping the matter would blow over if Robinson stayed out of sight.

Bates’s ploy didn’t work, and on July 17, 1944, army prosecutors charged Robinson with two offenses, neither of which related to the original incident on the bus. The first alleged that he had acted in an “insolent, impertinent and rude manner” to Bear by “contemptuously bowing to [Bear] and giving him several sloppy salutes.” The second charge claimed he had disobeyed Bear’s order to stay seated “on a chair on the far side of the receiving room.” If convicted, Robinson faced possible dismissal from the army, the equivalent of a dishonorable discharge.

For the army, the case came at a bad time. Two days after the incident, on July 8, 1944, the army had formally outlawed segregation on buses at military bases. “Restricting personnel to certain sections of such transportation because of race,” the directive stated, “will not be permitted either on or off a post, camp, or station, regardless of local civilian custom.” That same day, in Durham, North Carolina, a bus driver killed Private Booker T. Spicely after he had balked at going to the back of the bus. The army was in the awkward position of prosecuting charges against Robinson that arose from the enforcement of a Jim Crow rule that it now condemned and that had cost Spicely his life.

One person who realized the case’s volatility was Colonel Edward A. Kimball, commander of the 5th Armored Group, which included the 761st. On July 17, 1944, he phoned Colonel Walter D. Buie, chief of staff of XXIII Corps at Camp Bowie, Texas, and begged him to send an independent investigator. “This is a very serious case, and it’s full of dynamite,” Kimball explained, adding that the bus situation at Camp Hood “is not at all good” and that he feared “any officer in charge of troops at this Post might be prejudiced.” Buie refused to help.

Kimball was right about the case’s explosiveness. Robinson was a well-known athlete, and civil rights leaders and the African American press were keeping a close eye on Jim Crow incidents on military bases. Truman Gibson, a high-ranking War Department official, told an aide to “follow the [Robinson] case carefully,” and the army fielded inquiries about the matter from Senators Sheridan Downey and Hiram Johnson, both from Robinson’s home state of California.

TRIAL BY FIRE

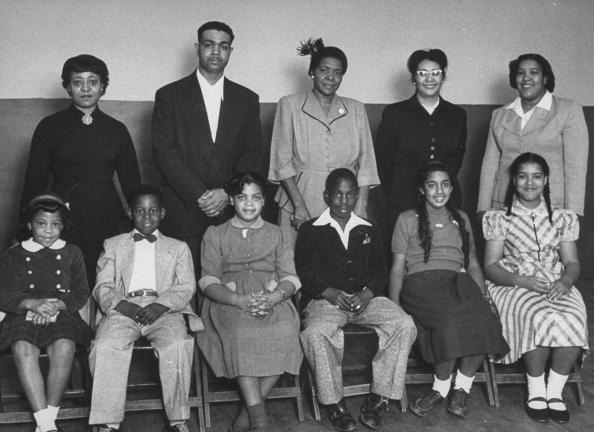

ROBINSON’S COURT-MARTIAL took place at Camp Hood on August 2, 1944, before nine officers, ranging in rank from captain to colonel. The trial transcript gives no detailed information about the judges, but historian Adam Kama has determined that two were African American. Robinson was represented by Lieutenants William Cline and Robert H. Johnson. Because the charges were limited to Robinson’s conduct in the guard room, the judges would hear nothing about the incident on the bus and little about events at the depot.

The prosecution called Bear, who described Robinson’s conduct on July 6 as disrespectful and disobedient, and Wigginton, who corroborated Bear’s testimony. Robinson took the stand and denied Bear’s account. He also told the judges just how hateful Muckelrath’s racial epithet was. Robinson said his grandmother, a former slave, had told him that “the definition of the word was a low, uncouth person,” before adding, “I don’t consider that I am low and uncouth…. I am a Negro, but not a n—-r.”

Robinson had an ace in the hole: Lieutenant Colonel Bates, his commanding officer. Bates testified on Robinson’s behalf and vouched for him as an exemplary officer. Two other officers from the 761st, Captain James R. Lawson and Lieutenant Harold Kingsley, also supported Robinson’s character.

The trial began at 1:45 p.m. and ended at 6 p.m., and the judges acquitted Robinson on both counts.

Although Robinson had been cleared, his military career was effectively over. Two weeks earlier, on July 21, 1944, army doctors had decided that his ankle injury was permanent, and the 761st would go to war without him. The Black Panthers would fight in Europe from October 31, 1944, through May 6, 1945, and earn a Presidential Unit Citation. With his outfit gone and a bad taste lingering from the court-martial, Robinson asked to be discharged because of his ankle injury. The army sent him to Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky, while his request was processed.

A SPORTS STAR IS BORN

AT CAMP BRECKINRIDGE, Robinson saw a Black soldier, Ted Alexander, tossing a baseball, and they struck up a conversation. Major league baseball barred Black players, but Alexander told Robinson there was good money to be made playing in the Negro Leagues, a network of all-Black professional teams. Alexander had pitched in the Negro Leagues since 1938, most recently for the Kansas City Monarchs. Although Robinson had made his name playing football, the idea of professional baseball intrigued him.

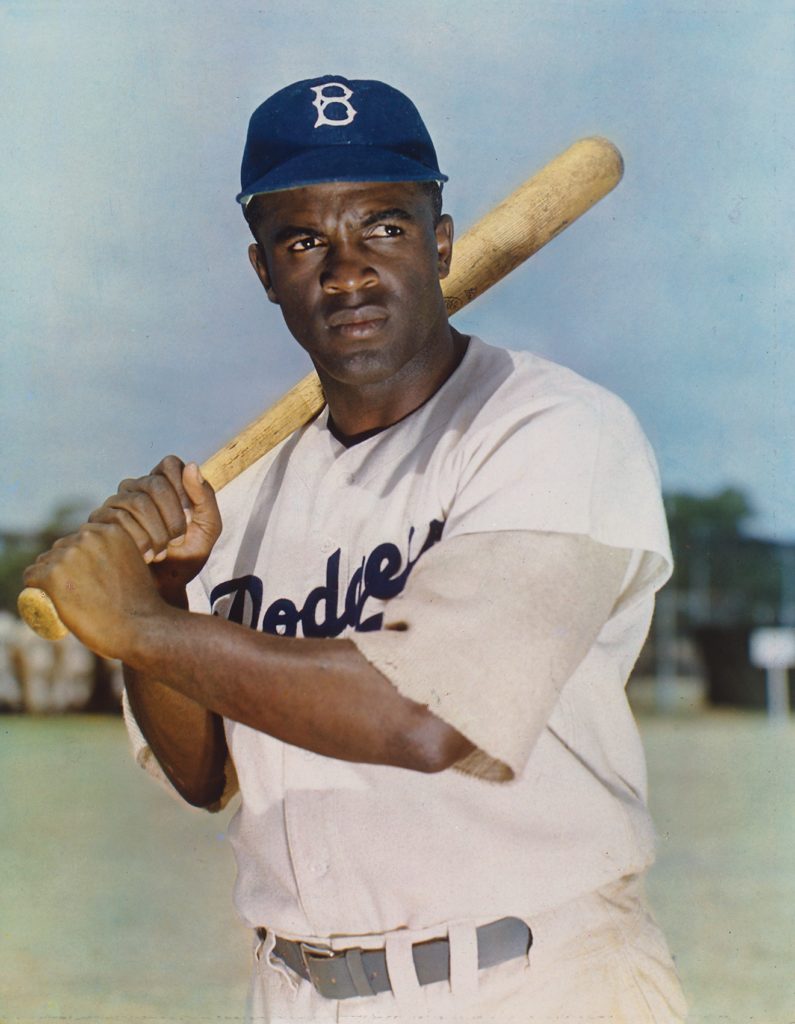

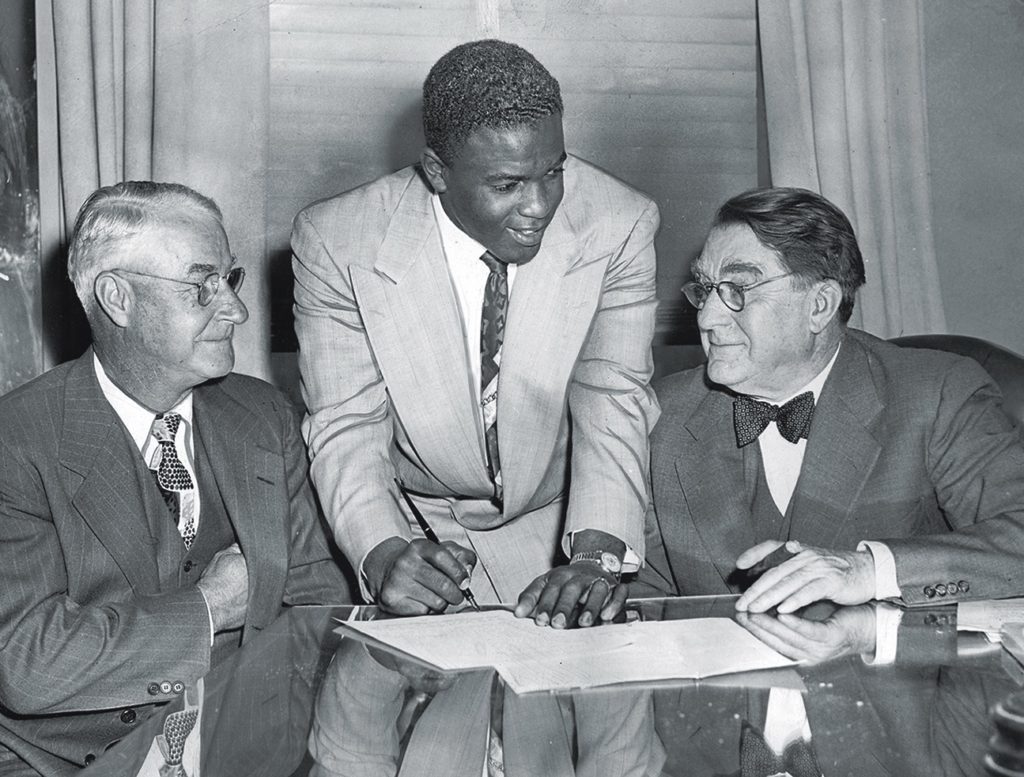

After he was honorably discharged on November 28, 1944, Robinson wrote to the Monarchs. The team signed him, and he played the 1945 season for Kansas City. Robinson’s play caught the attention of Branch Rickey, general manager of the major league Brooklyn Dodgers.

Major league owners had a long-standing agreement to keep baseball lily-white, but the Dodgers intended to change that, and Rickey was searching for the right player to break the color barrier. In addition to a talented athlete, Rickey wanted a man of unimpeachable character and firm inner strength. He knew that player would have to endure the vilest of racial slurs from fans and opposing players and, in some cities, he would be barred from the hotels and restaurants where his White teammates stayed and ate. Rickey conducted an extensive investigation of Robinson, a probe that undoubtedly included his service record. Satisfied with the results, he signed Robinson to play the 1946 season with the Montreal Royals, a Dodger farm team.

Robinson excelled in Montreal and earned a promotion. On Opening Day, April 15, 1947, at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, he was in the starting lineup for the Dodgers, batting second and playing first base, the first Black man to play major league ball since 1884. Surgery after the 1947 season fixed the ankle injury that had led to his army discharge, and he went on to a stellar 10-year career in which he batted .311 and helped lead the Dodgers to six National League pennants and one world championship. Robinson became an inspiration for African Americans, and his success opened the door for other Black players. He was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962.

When Robinson sat before the nine judges at Camp Hood, he couldn’t have known just how much was at stake. A conviction would have blemished his record and made him an easy target for those who wanted the major leagues to stay as White as their baseballs. Rickey would have looked elsewhere for his pioneer. But Robinson was acquitted, and the episode revealed a man of courage and conviction with the moxie to stand tall for human dignity—exactly what Rickey was looking for. ✯

Right of Way

When Colonel George A. Horkan took command of Camp Lee, Virginia, in February 1943, the camp had a racial problem, and Horkan knew he had to do something about it.

The civilian buses transporting soldiers to and from nearby Petersburg, Virginia, were a major source of friction. Drivers often refused to pick up African American soldiers, and when they did, they sent them to the back of the bus. This second-class treatment grated on Black G.I.s. Of Camp Lee’s 35,000 soldiers, 6,000 were African American.

“I knew something had to be done,” the 49-year-old Horkan told a reporter in early 1944. Virginia law required segregation on buses, but Horkan, a Georgia native, came up with a novel solution. He persuaded the bus company to reserve buses for soldiers only, ensuring there would be no civilian passengers to insist that Jim Crow segregation rules be enforced. Horkan also set up an integrated soldiers-only depot in Petersburg to guarantee that buses picked up all soldiers, regardless of race.

He wasn’t finished. While stopped at a traffic light in Petersburg, Horkan saw five white sergeants harassing two Black privates, and he took the sergeants’ names. The next day, he called them into his office and handed them a knife with orders to cut the stripes off their uniforms. They were now privates. Word spread, and soldiers at Camp Lee knew Horkan meant business.

In early 1944, Orrin C. Evans, an African American reporter for the Philadelphia Record, toured 10 military bases in seven southern states and interviewed scores of Black soldiers. At Camp Lee, he wrote, “I found morale unusually high, and virtually no evidence of race friction.” Evans credited Horkan, by then a brigadier general. The army took notice, and in May 1944, it approvingly sent Evans’s article to base commanders throughout the South. Two months later, on July 8, 1944, the army formally prohibited segregation on buses at military bases.

To Horkan, he had simply done his job. “Whenever you find a camp…where there’s constant racial friction,” he said, “you know the man at the top isn’t right.”

— Joseph Connor