The RTF was a service with a double life—flying on behalf of the Japanese, while also working against Japan as a secret collaborator of the OSS.

FOLLOWING A BRUTAL AND DEADLY DOGFIGHT dogfight in November 1944 with five Nakajima Ki-27b Royal Thai Air Force fighters, a young American P-38 pilot from the 449th Fighter Squadron wrote to his parents: “I didn’t even know we were at war with Thailand. Hell, I didn’t even know what Thailand was—I thought it was called Siam.”

His confusion is understandable. In July 1939, Siam had indeed changed its name to Thailand and, shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, declared war on the United States. Confusion about Thailand’s role in World War II, however, lingers to the present. Many military history buffs are not even aware that Thailand sided with Japan, nor that Thailand was the target of numerous U.S. Army Air Forces bombing raids, including the first B-29 combat mission.

The strange story of the Thai–Japanese alliance during World War II is far more nuanced than the sketchy versions in most historical sources, where aerial battles between Royal Thai Air Force pilots and their U.S. Army Air Forces adversaries are relegated to footnotes or a few obscure paragraphs scattered among dozens of sources. Yet those clashes in the air are as compelling and powerful as any in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater and add a vital dimension to the traditional CBI story. They’re even more remarkable because the Royal Thai Air Force was a service with a double life—flying on behalf of the Japanese, while also helping to fight Japan as a secret collaborator of the CIA precursor, the Office of Special Services (OSS).

By November 1941 the Thai government was certain that war was imminent between Japan and the United States. As the traditional buffer state between British Burma to the west and French Indochina to the east, Thailand resorted to doing what it did best: accommodation. That meant favoring the strongest power in the region, which most Thais viewed as Japan. Yet by training and association, Royal Thai Air Force (RTAF) sympathies rested more with the Americans than with the Japanese. This was in part because throughout the 1930s the United States had supplied almost all the RTAF’s combat aircraft. The best and brightest RTAF officers also trained in the United States at the Air Corps Tactical School, at Maxwell Field, Alabama, for most of the 1930s. There they developed lasting ties with their American counterparts and incorporated American tactics into the RTAF fighting doctrine.

Senior air force leaders, therefore, did not share the pro-Japanese sentiment of Thailand’s prime minister, Field Marshal Phibun Songkhram, and key segments within the Thai Army. Phibun, an admirer of fascism, became a supporter of Japan in 1940 when the Japanese mediated the brief war between Thailand and Vichy France. In return for Japan successfully pressuring France to cede Indochina border territories back to Thailand, Phibun became ardently pro-Japanese; he had clearly taken sides. The RTAF, on the other hand, stood ready to fight Japanese forces should they invade.

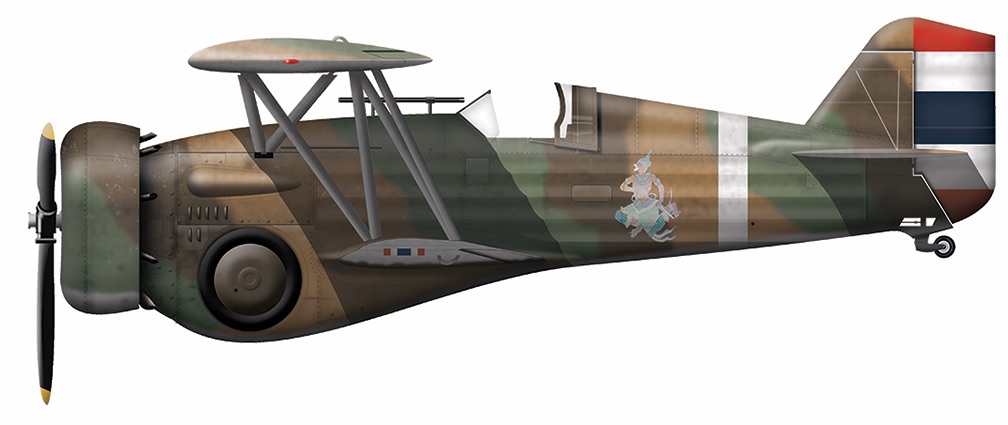

They didn’t have long to wait. At 3 a.m. on December 8, 1941 (December 7, Pearl Harbor time), units of the Imperial Japanese Army began landing along the Kra Isthmus, a narrow strip of land south of the capital city of Bangkok. In response, RTAF pilots from Wing 5, based on the isthmus, prepared to attack the advancing troops. They were quickly overwhelmed: Pilot Officer Maen Prasongdi took off first in a Curtiss Hawk III biplane fighter and, armed with four small underwing bombs, attempted to attack troopships in the eastern harbor before Japanese antiaircraft fire downed him. Another plane, piloted by Flight Sergeant Phrom Shuwong, had barely got off the ground when groundfire forced it to crash-land on the runway. As Phrom climbed out of his plane, Japanese soldiers shot him dead. Two more RTAF pilots met a similar fate while trying to get airborne. When Japanese troops and tanks surrounded the airfield, the wing commander ordered his men to burn all buildings on the airfield and fall back into the jungle to continue the fight.

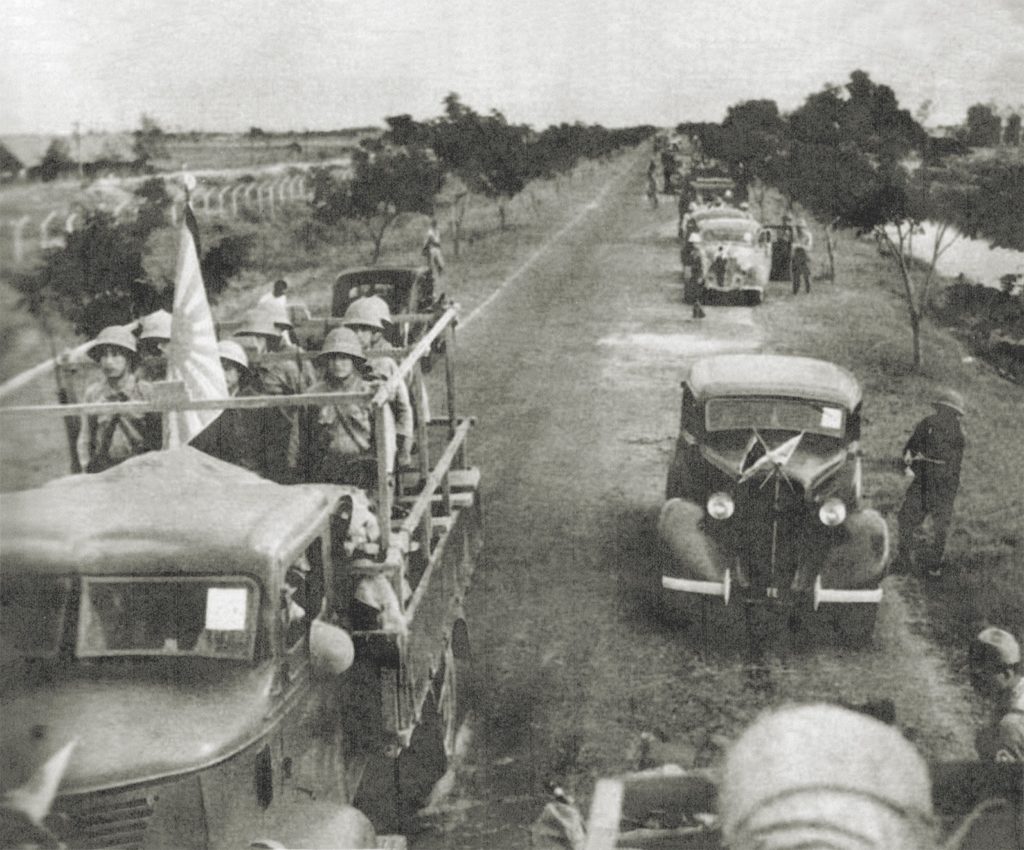

Farther north, at the Thai–Cambodia border east of Bangkok, the Japanese Imperial Guards Division smashed into Thailand against token resistance. Overhead, units of the Japanese Army’s 10th Air Brigade covered the advance with 11 Nakajima Ki-27 fighters—“Nate” to the Allies—and nine Mitsubishi Ki-30 (or “Ann”) light bombers. At approximately 6 a.m., pilots from the RTAF’s 43 Squadron spotted the Japanese aircraft overhead; three jumped into their Hawk IIIs to engage. In the brief dogfight that followed, the more-capable Nates—fighters with outstanding turning ability—quickly shot down all three Hawk IIIs, killing the pilots.

Shortly after 7 a.m., Field Marshal Phibun assembled his cabinet. They quickly concluded that further resistance was futile and, a half hour later, the Thai government announced a ceasefire. With virtually no other options, Thailand capitulated. Furious Wing 5 defenders blatantly disregarded the ceasefire order and continued fighting until noon the following day. The unit lost 38 men killed and 27 wounded; Japanese forces lost 115 killed.

An old Thai proverb holds that “the tree that bends with the wind is the tree that survives the storm.” When Japanese troops entered Bangkok late that afternoon, the die was cast. In the face of an invasion, overt threats of war, and Phibun’s pro-Japanese stance, Thailand bent with the winds of war. On December 21, 1941, the prime minister signed a Pact of Alliance with Japan and purged all who opposed the alliance from his government. A month later, when British Royal Air Force Buffalo fighters strafed Japanese-occupied airfields just inside the Thai border, Phibun took the unprecedented step of declaring war on the United Kingdom and the United States.

That declaration, and the pact with Japan, presented the RTAF with a distressing dilemma. Having just lost aircraft and pilots in battle against the Japanese, most air force leaders had no desire to cooperate with Japan. The RTAF commander, Air Vice Marshal Atueg Tevadej, finally settled the matter by announcing to his men: “You do not have to like the Japanese, but as professionals we must carry out Phibun’s orders.”

DURING THE EARLY MONTHS of 1942, British RAF bombers stationed in Burma occasionally sparred with Royal Thai Air Force fighters along the Thai border. After the Japanese 15th Army launched the main ground invasion of Burma from Thailand on January 22, air attacks gradually fizzled out as the Japanese advance left British aircraft out of range. As a result, the RTAF shifted most of its operations to northwest Thailand to support a new mission on behalf of Japan—driving Chinese troops from the eastern Shan States, a rugged, mountainous area bordering Burma, Thailand, Laos, and a small segment of China.

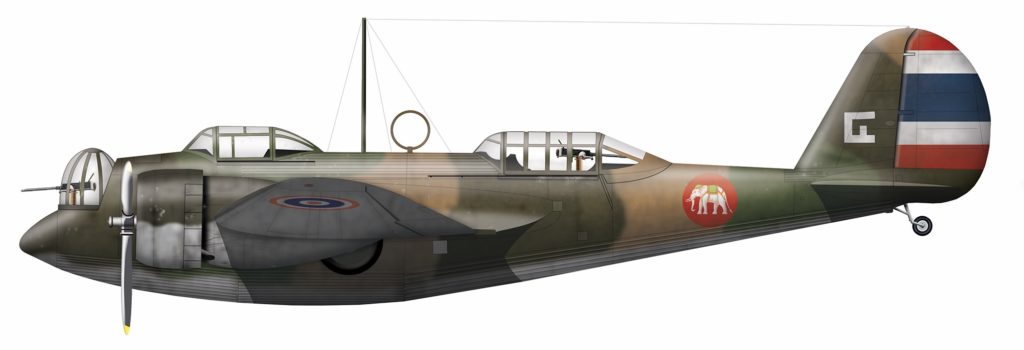

On May 10, 1942, the Thai Army began advancing into the Shan States. For the next nine months, the pattern of RTAF operations remained the same: Vought V-93 Corsairs and Curtiss Hawk IIIs handled most close-support missions, while Ki-30 light bombers, Ki-21 medium bombers, and export versions of the Martin B-10 bomber flew longer-range missions to strike Chinese troop concentrations in larger towns. No air-to-air combat occurred over the Shan States, but RTAF pilots plowed through plenty of ground fire and flak from Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek’s troops.

The bombing missions of late January 1943 were typical. On January 24, 17 Ki-30s from two RTAF squadrons bombed enemy positions to relieve the pressure on Thai Army units. Then, on the 29th, a mixed formation of 19 Ki-30s and Ki-21s armed with incendiary bombs attacked the Chinese stronghold at Mong Sae on the Burma-China border, setting buildings on fire and destroying a large arms depot. Both tactically and strategically, the raids were successful; a few days later the Chinese troops withdrew across the border into Yunnan Province.

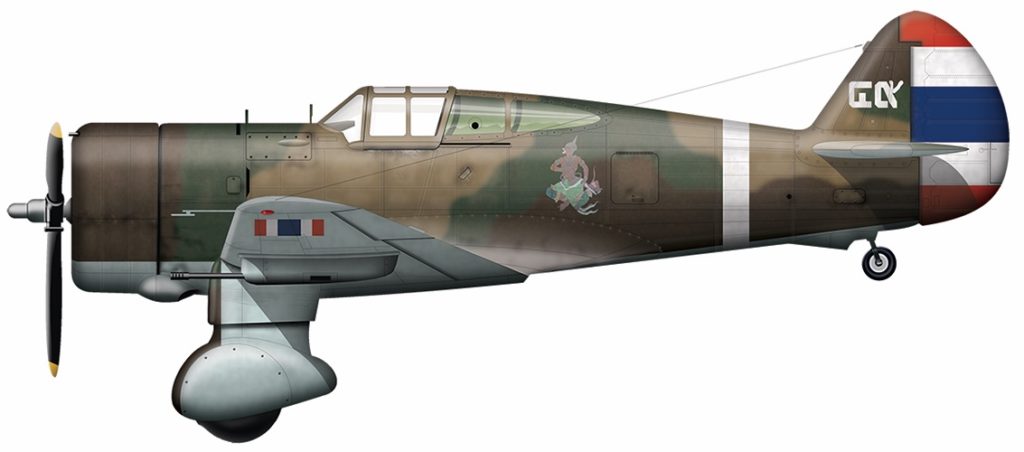

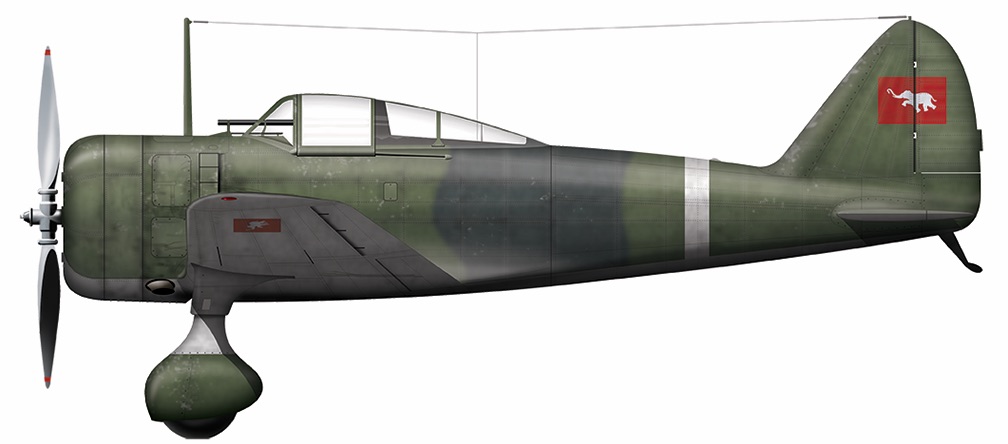

From January 1942 to December 1943, the Royal Thai Air Force upgraded its inventory with new equipment. As Japan’s only ally in the region, Thailand received a dozen updated Ki-27b Nate fighters and 24 Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscar” fighters. Similar to the Mitsubishi A6M Zero in both appearance and performance, the Oscar was light, easy to fly, and admired for its combat performance. It could outmaneuver most aircraft but, like the vaunted Zero, the Oscar lacked armor or self-sealing fuel tanks—meaning it was notoriously prone to disintegrating or catching fire after sustaining light damage.

As the U.S. Army Air Forces gained strength in the CBI Theater in 1943 by adding two new bomb groups and three new fighter groups, strategically important Bangkok moved near the top of the target list. The first raid of the new bombing campaign on the Thai capital occurred on the evening of December 19, 1943, when a force of 27 B-24 Liberator heavy bombers struck the city’s docks. Thai opposition amounted to searchlights and antiaircraft fire. A few nights later, on December 23, 26 Liberators bombed Bangkok’s central railroad station. During this raid, the American bombers spotted two airborne enemy aircraft, but neither attacked. On these early missions, the RTAF was unprepared and ineffective. Because they had no radar or early warning system, RTAF fighters didn’t scramble until the bombers were practically overhead. By the time they reached altitude and searched around in the darkness, the bombers had already departed.

From its bases in China, the U.S. Fourteenth Air Force—under the command of Major General Claire Chennault, the legendary leader of the Flying Tigers—directed its raids at targets in northwest Thailand, focusing on headquarters complexes and communication centers around the cities of Chiang Mai and Lampang. In a daring unescorted daylight raid on December 31, 1943, a formation of 25 B-24s bombed the railroad marshalling yards at Lampang. Six Ki-27 Nates from the RTAF’s 16 Squadron tried to intercept the B-24s, but the American crews reported that the Thai fighters, in their first encounter with Fourteenth Air Force heavy bombers, initially held back from attacking and jinked away when the B-24s opened fire. Three days later, two P-38 Lightnings from the 449th Fighter Squadron escorted 28 B-24s on a second mission to Lampang. Again, Thai fighters scrambled but did not attack. The RTAF’s apparent lack of aggressiveness stemmed not so much from an absence of nerve but from scarcity of information. Even in broad daylight, the inadequate forewarning that resulted from a lack of ground radar guidance meant they could do little.

Since 400 miles of highways and rail lines linked Bangkok and Chiang Mai, Fourteenth Air Force B-25 medium bombers joined the interdiction battle on March 5, 1944. For the remainder of the spring, the B-25s’ principal targets were those vital roads and rail bridges. Frustrated Thai pilots rarely intercepted the Americans. On one occasion a Hawk 75N pilot scrambled and mounted an attack against B-25s bombing the Ban Dara bridge just south of Lampang. Thai records indicate that the RTAF pilot only made one firing pass; his fighter was too slow to catch up with the bombers. To counter B-25 raids, the Thais switched to overlapping daylight combat patrols—none of which were successful. A respite from bombing attacks only occurred during the summer when monsoon rains curtailed Allied operations.

DURING THE FIRST HALF of 1944 two major military operations indirectly put Thailand in the crosshairs of the newest and most technologically advanced U.S. Army Air Forces strategic bombers. In early March the commander of the Japanese 15th Army, Lieutenant General Renya Mutaguchi, launched “Operation U-Go”—the invasion of India. Since much of the logistical support for his operation originated in Thailand, the Allied air offensive against Thai targets heated up in spades.

Thailand also became an unlikely player in the Allies’ “Operation Matterhorn.” The strategic plan for this operation—approved at the Quebec and Cairo Conferences of 1943—involved stationing squadrons of new long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers in India and China, where they would carry out strategic raids against mainland Japan.

Brigadier General Laverne G. Saunders—ironically nicknamed “Blondie” because of his jet-black hair—assumed command of the newly formed 58th Bomb Wing at Kharagpur, India, at a hastily constructed base for the first operational B-29 unit. The commander had his hands full: an unproven and unpredictable brand-new airplane, inexperienced aircrews, and a logistics system unable to supply sufficient fuel or spare parts. To work the kinks out, the B-29s of the 58th Bomb Wing were assigned their first combat mission: a raid on June 5, 1944, against the railroad yards in Bangkok.

A total of 98 B-29s took off on the mission: one crashed on takeoff, killing the entire crew, and at least 20 others aborted for mechanical reasons. The first B-29 to fire a shot in anger was over the target at 10:52 a.m., where heavy cloud cover obscured the railroad yards, forcing half the planes to bomb by radar. Since few crews had received instruction in radar bombing, they by necessity resorted to “on-the-job training.”

During the mission, nine RTAF Oscars scrambled to intercept the stream of bombers, with virtually no success. The return trip for the B-29s proved to be considerably more hazardous. One crew ran out of fuel and bailed out, two B-29s crash-landed, and two ditched in the Bay of Bengal. Despite 15 men dead, two missing, and the total loss of six B-29s, XX Bomber Command touted its first combat mission as a success. It glossed over the fact that photo reconnaissance showed that only 18 bombs hit near the intended target. The damage, to quote the tactical mission report, “would cause no noticeable decrease in the flow of troops and military supplies into Burma.”

During the Operation Matterhorn B-29 raids on Bangkok, the mission on November 2, 1944, was the only one where RTAF pilots drew blood. On this daylight raid, 55 B-29s attacked the railroad marshalling yards on the outskirts of Bangkok. Opposing them, the Thais scrambled seven Oscars. At the controls of his Oscar, Flight Lieutenant Thorsak Worrasap fired on one B-29, setting the big bomber ablaze. He attempted to follow his prey but return fire from the other bombers hit Thorsak’s fighter, forcing him to bail out.

One of the largest documented battles between RTAF and U.S. Army Air Forces fighters occurred nine days later over Lampang in northwest Thailand. On November 11, 1944, nine P-51C Mustangs from the 25th Fighter Squadron and eight P-38 Lightnings from the 449th flew an armed reconnaissance mission into the area. During their initial attack, the American fighters strafed and damaged a locomotive before moving on to a nearby airfield. That brief delay gave five RTAF Ki-27b Nates from 16 Squadron a chance to scramble.

The Nates reached their patrolling altitude just as the American fighters strafed Lampang Airfield, destroying one aircraft on the runway. As the RTAF pilots maneuvered to attack, the top-cover P-38s rolled into action, each belching 20mm shells from a single cannon and streams of fire from four .50-caliber machine guns. The five Nates immediately split into two groups, with Flying Officer Kamrop Bleangkam and Chief Warrant Officer Chuladit Detkanchorn engaging the P-38s, while the other three Nate pilots tried to fend off the Mustangs. During the furball dogfight that ensued, the nimble Nates for the most part outmaneuvered their adversaries but, badly outnumbered and outgunned, the Thai pilots had little chance in the lopsided fight. Kamrop latched onto one P-38, claiming to have sent it down with its right wing in flames before another Lightning jumped him, forcing him to crash-land. Yet another P-38 downed Chuladit.

Armed with only two 7.7mm machine guns, the Nate didn’t pack much of an offensive punch compared to the P-51C’s four .50-caliber machine guns, but several RTAF pilots put their armament to good use against the Mustangs. As four P-51s climbed to join the P-38s engaging Kamrop and Chuladit, Second Lieutenant Henry Minco shouted, “I see two below and am going after them.” Diving into the swirling dogfight, Lieutenant Minco, on his 71st combat mission, was never seen again. Much later, stories drifted in from Thai contacts that Minco was dead. They also reported that missionaries buried the American pilot.

As the dogfight continued over Lampang, RTAF Flight Lieutenant Chalermkiat Vatthanangkun flew into a wall of .50-caliber tracers, his Nate absorbing multiple hits to its engine. Chalermkiat made a forced landing, after which one of the Mustangs strafed and destroyed his fighter. As the uneven battle ended, P-51s destroyed the two remaining Nates: Chief Warrant Officer Thara Kaimuk was shot down and crashed nine miles from Lampang; Chief Warrant Officer Nat Sunthorn died when his Nate crashed.

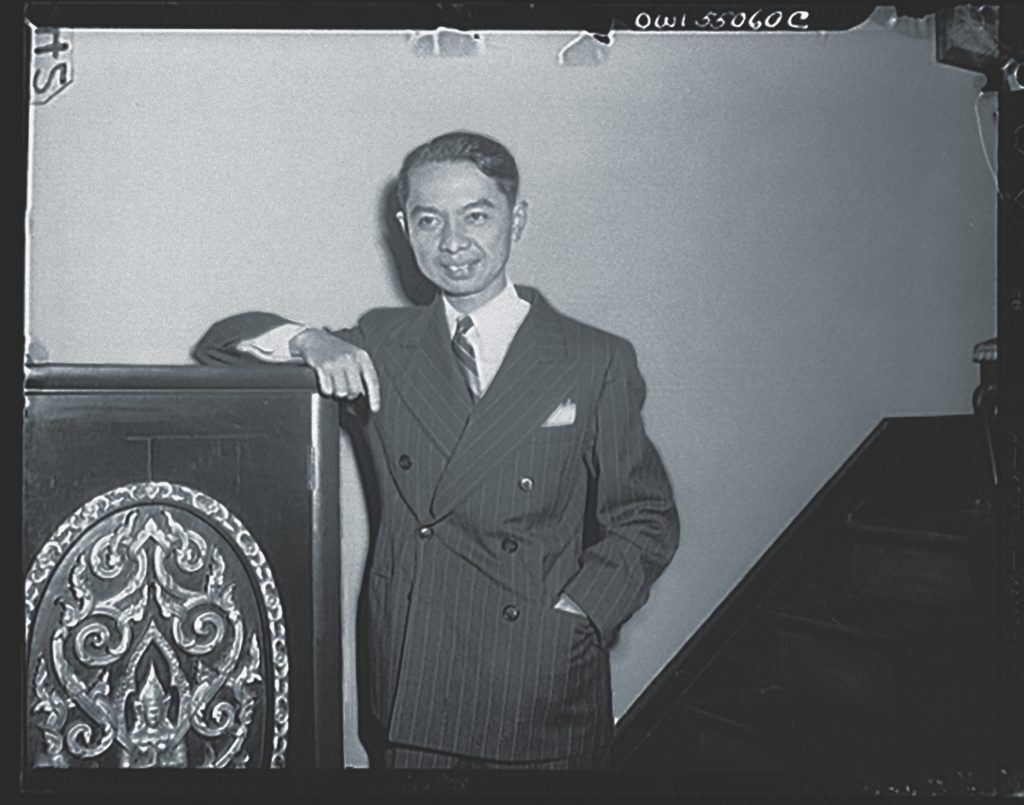

WHILE THESE AIR CAMPAIGNS were going on, an underground resistance movement had been growing since the first days of the war. The Free Thai Movement—or Seri Thai—had arisen immediately after Thailand declared war on the United States in 1942. The Thai ambassador in Washington, D.C., Seni Pramoj, refused to present the declaration of war to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, instead suggesting to Hull that he might “organize and preserve a government of true patriotic, liberty-loving Thais while my government is in the clutches of Japan.” Washington, wisely, opted to regard Thailand as an occupied—rather than belligerent—nation. Ambassador Seni, a conservative aristocrat whose anti-Japanese credentials were well established, organized the movement with American assistance.

Enter the OSS. On March 12, 1942, Seni submitted a proposal to infiltrate a group of Thai students in the U.S. into their homeland for subversive operations. Seni’s staff then met with the OSS’s Lieutenant Colonel Garland H. Williams to arrange for the young volunteers to be trained, equipped, and deployed. The first group of 13 Thais began OSS training on June 12, 1942. Many of the young Thais, trained at the various OSS camps in Maryland and Virginia in 1942, were parachuted into Thailand in 1944 and 1945 for espionage work, to organize guerrilla networks, and to send back useful intelligence. They also helped rescue downed Allied aviators.

One of the most dramatic rescues was of a Flying Tigers P-40 pilot, Lieutenant William D. McGarry—an ace with eight victories. On March 24, 1942, McGarry was downed by antiaircraft fire over Chiang Mai, captured, and interned in a compound at Thammasat University in Bangkok, where he was monitored by Thai—not Japanese—guards. Unbeknownst to the Japanese, he was also under the watchful eye of none other than the university’s rector, Pridi Phanomyong—a key leader of the Free Thai movement. After connecting with an OSS-trained Thai national who had been parachuted in on September 9, 1944, to assist him, Pridi informed the Japanese that McGarry had died in captivity; the pilot was then smuggled out of the prison camp in an improvised coffin and hidden in a Thai customs boat with four Royal Thai Air Force officers. McGarry’s escape helped strengthen the United States’ alliance with a reluctant enemy and energized the RTAF’s double life.

Although the RTAF had no role in forming the Free Thai Movement, the relationship had been growing since April 1943, when Group Captain Tevarit Panleuk took over as the new RTAF commander. Secretly pro-American and a graduate of the Air Corps Tactical School, he was even more sympathetic to the movement than the former chief and allowed Free Thai to use air force facilities and equipment for their underground activities.

Beginning in mid-1944 when American OSS agents began parachuting into Thailand, the RTAF offered its aircraft to transport those agents wherever they were needed, providing what amounted to a clandestine airline. The underground airlift became so successful that RTAF aircraft began flying agents directly into Bangkok’s Don Muang Airfield, which it shared with the Japanese.

For the Allies, the daunting task of providing supplies and weapons to the growing Thai underground was made easier by having access to secret airfields the RTAF set up in 1944–45. RTAF aircraft could then distribute the supplies around the country, right under the noses of Japanese forces. Additionally, the RTAF provided the Allies with weather information, real-time Japanese troop movements, and potential targets for American fighter/bomber raids. In one case, an RTAF officer even flew with American bombers on several missions against Thailand to ensure that targets were accurately identified.

Continued American air raids against targets in Thailand placed the RTAF in an ethical predicament. Having provided much of the intelligence on Japanese air strength, the RTAF was forced to watch its own men and equipment attacked alongside the Japanese. For example, on April 9, 1945, near the city of Lopburi, about 80 miles north of Bangkok, marauding Tenth Air Force Mustangs strafed the joint Thai–Japanese airfield, destroying 15 RTAF aircraft. As a result, the quandary ate at their guts: how to defend targets when you provide vital intelligence to an enemy bombing those targets?

The monsoon’s arrival in May 1945 provided not an answer but a solution, as the rain drastically curtailed the bombing effort against Thailand. Attacks on Thai airfields ceased for all practical purposes, as did clashes between RTAF and Allied aircraft. Subsequently, until the end of the war, the RTAF devoted most of its sorties to supporting the Free Thai Movement.

Japan’s surrender brought the Royal Thai Air Force’s double life to an end. The RTAF had never wanted war with the United States. Yet, boxed into a corner by political events, it had performed its duty to king and country as a reluctant ally of the Japanese and as an even more reluctant enemy of the United States. How did they pull this off? A Free Thai Movement member explained: “The Japanese increasingly dealt with Thailand as a conquered territory rather than as an ally. Because of their feelings of superiority and their attitudes toward the Thai, the Japanese could never believe that the friendly Thai among whom they lived could be capable of such skillful subversion.” As a key part of that subversion, the RTAF occupied an unprecedented position during the war—fighting and aiding the same foe. Throughout its double life, the RTAF had the courage and tenacity to work behind the scenes for a virtuous cause much bigger than any alliance with Japan: the Free Thai cause. ✯

This article was published in the August 2021 issue of World War II.