Given the problems the Confederates faced in the Western Theater, it’s remarkable they kept going as long as they did

The Civil War—indeed, all of American military history—contains few stories as sad as that of the Army of Tennessee. In his new book Conquered: Why the Army of Tennessee Failed (UNC Press, 2019), Larry J. Daniel draws from extensive research in primary source material and effectively engages recent scholarship to make yet another a major contribution to literature on the war in the West. He describes and analyzes the problems the army and its leadership experienced as it endured failure after failure and offers compelling accounts of the hardships service in that army entailed in a work that merits a place on the bookshelf of anyone with an interest in the course, conduct, and outcome of America’s bloodiest war.

You do such a great job here capturing just how depressing the story of the Army of Tennessee is that I have to ask: What keeps you returning to it as a subject of study?

It is easy to see why the soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia kept fighting—they had Robert E. Lee and battlefield victories. The more compelling story, it seems to me, is why the men of the Army of Tennessee kept fighting despite weak leadership and battlefield losses. Defeat, in many respects, makes for a more gripping narrative than victory.

You make a strong case that the Army of Tennessee to a certain extent was doomed from the start. What were the problems with the army and the Confederate cause in that region that led you to this conclusion?

When I examined the DNA of the army and the region, I discovered that many issues were “baked in” from the outset. One of these influences was sectionalism. The troops of the Upper South, Lower South, and the Highlands never really meshed, not at least until early 1864. This led to suspicion, different war aims, and infighting. Another issue was the geography of the West. Unfortunately for the Confederates, the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Cumberland Rivers all went in the wrong direction. The inability to stop the Union Navy proved pivotal. Perhaps P.G.T. Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston were right—that is, that the Confederates should only marginally have defended the rivers and checked the Federal armies as they advanced inland. But was it politically viable only to perfunctorily defend the cities of Nashville, Memphis, Vicksburg, and New Orleans? This geopolitical issue proved unsolvable and led to military disaster.

A critical factor in military success is, of course, leadership. Despite efforts by recent scholars to present more sympathetic takes on them, if there is an American army commander who stands lower in the eyes of posterity than Braxton Bragg and John Bell Hood, his name escapes me. Do these two officers deserve this fate?

By Larry J. Daniel

University of North Carolina Press, 2019, $35

The pendulum had clearly swung too far in one direction, and in that sense we all owe Earl Hess (in the case of Braxton Bragg) and Stephen Hood and Brian Craig Miller (in the case of John Bell Hood) a debt for their reappraisals. Bragg had a complicated personality. He was not social and desired people to get to the point. He ate by himself, and he was criticized for never visiting the hospitals. There were flashes of greatness, but his unfortunate personality traits proved his greatest handicap. Hood was not a laudanum-addicted butcher who was dismissive of mass casualties. Indeed, the battles around Atlanta were his attempt to avoid direct attacks against earthworks. In the end, I think Albert Castel got it right—Hood simply tried to do too much with too little.

You no doubt notice I left Albert Sidney Johnston, Pierre G.T. Beauregard, and Joe Johnston out of the previous question, as historical opinion on them has been more mixed. Clearly, none of these men delivered the results the Confederate government hoped for, so how do you assess their leadership?

I have never been a fan of Albert Sidney Johnston. In the 22 weeks that he commanded the army, he lost Kentucky and Tennessee, surrendered a 16,000-man corps at Fort Donelson, and he failed to destroy the Federal army on the first day at Shiloh, despite having numerical superiority, the tactical surprise, and the incredible good fortune of having Lew Wallace’s Union division thrashing about in the woods rather than on the battlefield. William J. Hardee and Jeremy Gilmer, who spent extensive time with the general, were unimpressed. Yet several Western historians remain strangely bedazzled. Whether or not he could have evolved and ultimately become a great general is a question that his supporters love to indulge, but of course it is a non-historical question. Beauregard’s major contribution in the West was forcing Leonidas Polk to withdraw his corps from Columbus, Kentucky, something which Sidney Johnston had been unable to accomplish. Had Polk gotten his way and remained at Columbus, it is highly possible, almost predictable, that his corps would have gotten bottled up and surrendered. With a corps captured at Fort Donelson and another at Columbus, Confederate resistance in the West would have been badly, if not fatally, shattered in early 1862. As for Joseph E. Johnston, Richard McMurry is nearing completion of his extensive biography on the general which will be a major addition. I believe that once Johnston surrendered the high ground in North Georgia in the spring of 1864 there was little chance of holding Atlanta.

While it rained on both sides, it cannot be denied there were moments during particular campaigns in which the Army of Tennessee seemed to fall victim to plain old bad luck in having the wrong guy in the wrong place at the wrong time. Do any of these in particular stand out from the others in your mind where an opportunity to tip the scales decisively in the army’s favor and reverse the tide of the war in the West was irretrievably lost?

In terms of reversing the tide of the war in the West—no. Even if U. S. Grant’s army had been destroyed at Shiloh, I do not believe that the North would have sued for peace. The Confederates lost a field army at Vicksburg, but they kept on fighting. Nor do I adhere to the popular theory that if Southerners had held on to Atlanta until after the 1864 Northern election that Lincoln would have been defeated. The “South could have won by not losing” theory is, in my view, flawed.

What kept the men in the ranks going? I mean, at some point didn’t some of them figure out the Confederate cause were ultimately doomed and they were enduring a lot of hardship, especially those with families, with little prospect of victory?

This is an interesting question and one that is explored in a book that deserves more attention than it has gotten—Jason Phillips’ book Diehard Rebels. False reporting on the part of the Southern press, the fog of war, rumors, religion—all played a part. In the early part of the 1864 Tennessee Campaign, Rebel morale remained remarkably high. I have a chapter in Conquered titled “The Pathway to Victory” in which I examine this issue

It is said there are few atheists in foxholes; on the other hand, there is no better place for breeding vice than a disgruntled army camp. How did religious faith factor into the lives of the men of the Army of Tennessee?

The Army of Tennessee underwent two major religious revivals—in 1863 and again in early 1864, although I would not quibble that it was really one extended revival. In order to win God’s favor, the men believed that they had to rid themselves of evil—gambling, prostitution, alcoholism, cursing, etc. Unfortunately, the higher moral issues of slavery and war were not questioned. The message of the revivals was clear—suffering and death in a righteous cause was not to be feared. The spring 1864 revival was an essential glue that kept the army together. The re-enlistments took on the aura of a revival—background music, speeches (sermons), and the men removed their hats and made solemn pledges (professions of faith). The men responded within the context of their culture.

You devote considerable attention to problems with the army’s mounted arm, yet Confederate cavalry usually gets good reviews from historians. What are we to think of Joe Wheeler and Nathan Bedford Forrest?

I give Joe Wheeler bad marks. He was personally brave but in entirely over his head. In January 1865, Alfred Roman inspected the army’s cavalry. He declared that Wheeler was fit to command only a brigade or a division and recommended his removal. As for Forrest, I will admit that I have been influenced by David A. Powell’s 2010 book Failure in the Saddle, which is not complimentary of Forrest. Powell did not believe that Forrest should have been given command of the army’s cavalry—he simply lacked the temperament for such mundane cavalry tasks as intelligence-gathering and protecting flanks.

When the reasons for defeat at Gettysburg were being debated, George Pickett is famously said to have said he believed the Yankees had something to do with it. Having studied both the Army of the Cumberland and Army of Tennessee, to what extent would you say the Army of Tennessee’s difficulties were tribute more to Union effectiveness or the internal problems you document so effectively?

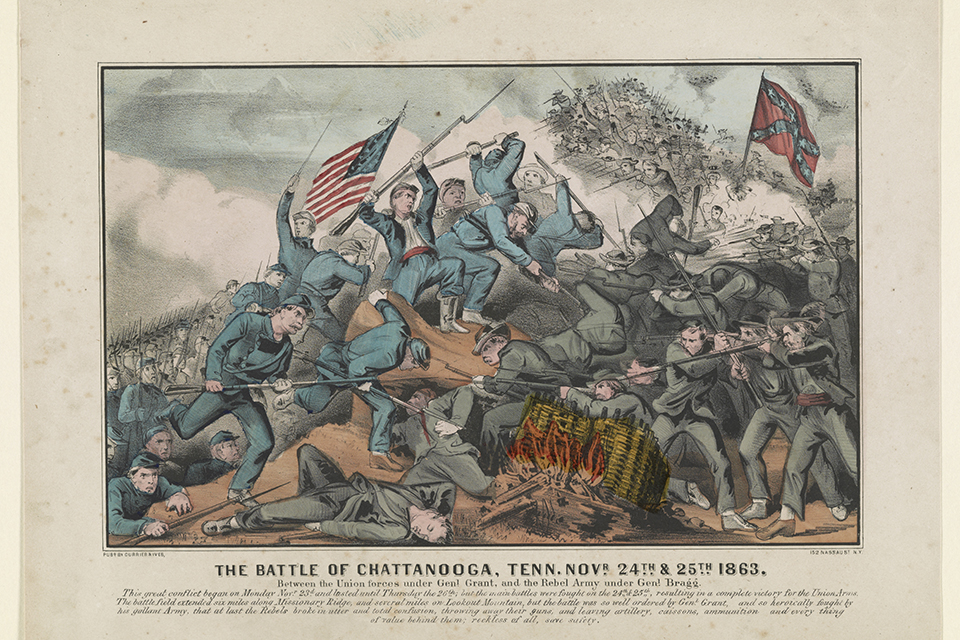

Nothing in the way of geography—not the Tennessee River, not the Cumberland Mountains, nothing could stop the Army of the Cumberland. The Western Federals also had a deeper leadership “bench” than the Army of Tennessee. Additionally, the Western bluecoats were unquestionably a tough breed. The rapid rebounding after the initial routs at Shiloh, Stones River, and Chickamauga and the charge up Missionary Ridge bore evidence of their prowess.

Given all operational and material disadvantages you chronicle, the hardships they endured, and Northern determination to preserve the Union, should we perhaps—following the thinking of Gary Gallagher—be more impressed by the fact that the commanders and men of the Army of Tennessee were able to keep fighting for four years than by the fact that they were ultimately conquered?

It is indeed remarkable that the Army of Tennessee maintained a lethal edge as long as it did. But the Confederates were not the only ones who made mistakes. I list several costly Union strategic errors in the book that potentially had the effect of extending the war.