Frank Huston “was an ‘Unreconstructed Reb…who had no good word for any man who wore the blue,” Col. William A. Graham wrote in “The Custer Myth,” published in 1953. “Though he denied that he fought with [the Plains Indians], how else did he go about it to ‘even up the score’?”

Graham himself had worn the blue. Trained as a lawyer, he had served along the Mexican border in 1916–17, later joined the Judge Advocate General’s Corps and retired from the Army in 1939. Having corresponded with Huston in preparation for his book, he remained on the fence as to whether Frank had fought George Armstrong Custer at the June 25–26, 1876, Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Arthur Sullivan Hoffman, who edited articles Huston wrote in the early 1920s for the pulp magazine Adventure, believed Huston had fought Col. Custer but was never able to provide Graham with solid proof. Huston himself talked around the subject.

“I was a squaw man, yes,” he wrote Graham in 1925, “but I was not present at the Little Bighorn. I was 50 miles away, headed thereto. But O—how I would have liked to have been there! Yet as a matter of fact, there were white men there; not with the Sioux, but with other nations present. Put yourself in their place. Would you, then or now, acknowledge it?”

GENUINE KNOWLEDGE

Huston’s knowledge of Indian customs and culture was genuine, and his knowledge of the battle seems first-hand, if contrary to stereotypes on both sides.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

“I judge that [Major Marcus] Reno (as one of his ‘skippers’ later told me) became rattled,” Huston wrote Graham, “but he did not stampede and saved his command by pushing up the bluffs. That the battalion did stampede, I concede, but our people (i.e., the Indians) had ‘put the fear of God’ into the men. Reno’s record in the War Between the States refutes any accusation of cowardice; but he was ignorant of Indian methods of fighting and made a convenient ‘goat.’

“While I believe there were white men with the Indians at the Little Bighorn, they were not with the Sioux, because [Sitting] Bull was ‘peculiar’ and at such times objected forcibly to the presence even of half-breeds.”

“[Huston’s] personal history was a sad one,” Graham noted. Frank told the author he had grown up in Richmond, Va., and was a teenaged Confederate soldier during the last years of the Civil War. “He was a youth doing a man’s work in the ranks of [Robert E.] Lee’s army,” Graham wrote.

“When Richmond fell, his mother, who had remained at the family home, was assaulted and beaten with rifle butts by drunken soldiers of [Maj. Gen. Godfrey] Weitzel’s command, who were the first to enter the city. She died as a result of her injuries, and her son was never able even to locate her grave.

EMBITTERED BY TRAGEDY

“That this shocking tragedy embittered him is easy to understand; and shortly after the cessation of hostilities, he made his way West, without taking the oath of allegiance, and joined the Sioux, determined to ‘even the score against the blue bellies,’ as did many others.”

While the story is not impossible, Gen. Weitzel’s leniency to Southern civilians, his distribution of rations, and his chivalrous posting of armed Union guards at the home of General Lee’s wife, Mary, who had remained in Richmond, are well recorded. Most historians concur homegrown looters did far more damage to the Confederate capital than did federal soldiers.

That Huston lived with the Lakotas is beyond doubt, borne out by specifics from his correspondence with Graham.

“From ’66 to ’81, with some time off, I was mainly in tepees,” he wrote, “and in all that time I never saw a grown male white taken prisoner, nor heard of one.” Contemporary accounts suggest Lakotas killed enemy combatants quickly. That they scalped dead male enemies and mutilated their bodies—thus crippling them in the afterworld, according to their beliefs—was mistaken for torture by horrified soldiers and may have prompted some at the Little Bighorn to commit suicide rather than surrender.

‘THIS IS OUR COUNTRY’

“I find almost no one with a proper understanding of the attitude of Bull et al.,” Huston wrote. “As Tatanka (i.e., Sitting Bull) said, ‘We ask only to be left alone.’ ([Black] Kettle said the same.) ‘All we wish is that you yellow-faces keep out of our country. We don’t want to fight you. This is our county. The Great Spirit gave it to us. Keep out, and we will be friends.’

“Although somewhat addicted to snobbishness,” Huston continued, “yet I hate pretense, and George Custer has always been anathema to me. His massacre of Kettle’s band on the Washita was a fitting supplement to Sand Creek, where Kettle’s first abuse by whites occurred.

“If you go into a fight, highly confident of your ability to whip 10 times your weight in wounded wildcats and suddenly find the shoe is on the other foot, then you may get a true idea of ‘Le Grand Poseur’ and his command.”

‘RUN OF THE ARROW’

While Huston may not have been in on the finish at the Little Bighorn, his participation in another key event of the Indian wars is well established. In 1886 he signed on as a packer with Lt. Charles Gatewood’s successful expedition to convince Apache Chief Geronimo to surrender. A photo from that campaign (opposite) reportedly shows Huston, though his identity remains unverified.

However, a Hollywood director may have based a movie on the “Unreconstructed Reb.”

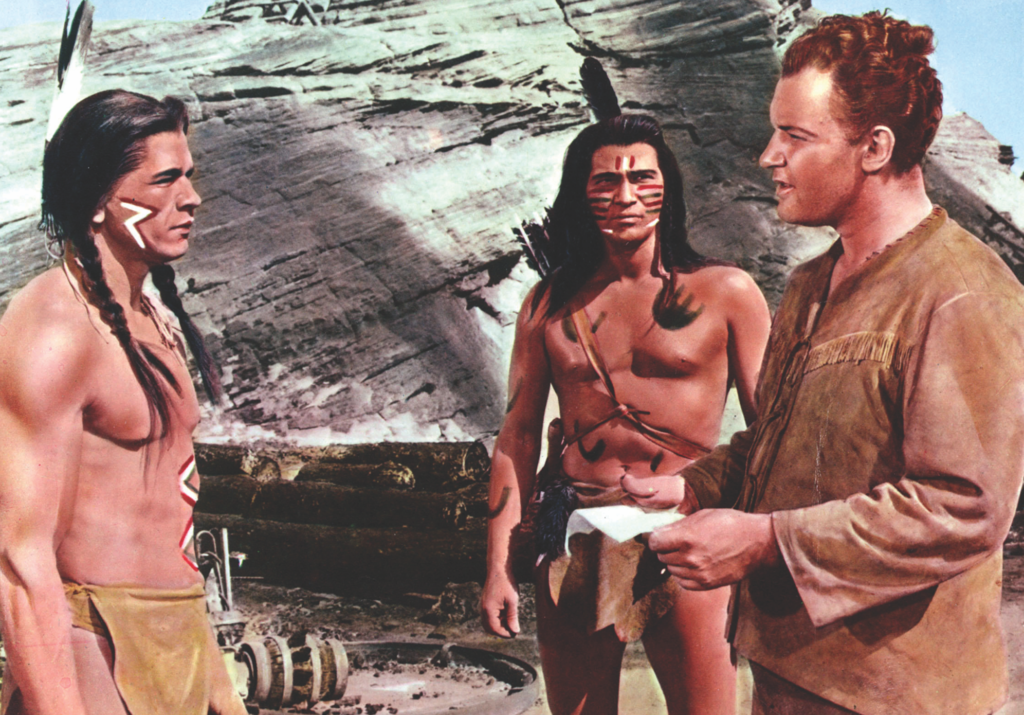

In 1957 Sam Fuller filmed “Run of the Arrow,” about an Irish Confederate named O’Meara (portrayed by Rod Steiger) who at war’s end refuses to surrender, instead heading west and eventually marrying into a Sioux band under the fictional Blue Buffalo (Charles Bronson).

O’Meara respects them to a point but is appalled by their torture of a glory-seeking officer (Ralph Meeker), whom they’d captured after massacring his command. O’Meara ends the officer’s agony by shooting him. Frank Huston might not have endorsed the ending.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.