Preservationists, residents, entrepreneurs and Civil War enthusiasts all want a stake in its legacy

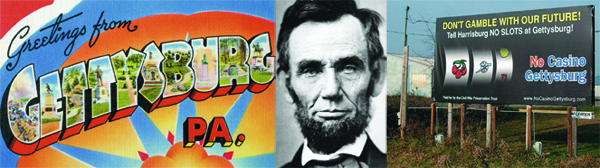

At times it seems as if there isn’t enough Gettysburg to go around, and almost 150 years after the nation-changing battle, the site remains a hotly contested territory. Local souvenir hawkers vie with Civil War zealots. Developers skirmish with preservationists. Longtime locals oppose plans floated by faraway fans.

And none of this is new.

Controversy enveloped Gettysburg even before it became a bloody battleground, igniting with the founding of a soldier’s cemetery in 1862 and seldom subsiding since. In the 1890s, one fight made its way all the way to the Supreme Court, and sparring grew particularly intense during what has been glibly referred to as the Second Battle of Gettysburg, a four-decade free-for-all bracketed by the erection of an observation tower in the early ’70s and the (second) rejection of casino gambling earlier this year.

What gives? Why all the squabbling?

In one sense it’s a nice problem to have. “Gettysburg is the crown jewel of Civil War battlefields,” said writer and attorney Eric Wittenberg. “There are people whose only interest is the Battle of Gettysburg; they don’t care about other Civil War battles.” Wittenberg loves Gettysburg, has written books on Gettysburg and has visited innumerable times since he first saw the battlefield as a third-grader. But he lives in Ohio. “I wouldn’t live [in Gettysburg] in a million years,” he said. “I have enough drama in my life.”

By contrast, Mark Snell, director of the George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War in Shepherdstown, W.Va., does live in Gettysburg, and has for decades, not that it helps his standing much. “All the time, I hear, ‘You historians need to stay out of it.’ But I live there, I pay taxes there and I’m less than a five-minute drive from the battlefield.” No matter. Even after all these years, Snell acknowledges that he is still considered a newcomer. And who isn’t a newcomer? For the answer to that, you might look for clues in the founding settler culture of the 1700s.

The Great Wagon Road leading out of Philadelphia improved on old Iroquois footpaths that stretched westward to Lancaster and Gettysburg before heading south to Virginia and the Carolinas. British and Germanic peoples established the hamlets along the way, where their influence remains strong. They were admired for their thrift and industry; on the flip side, they did not take kindly to anything that might come between them and their profits. The right to the land and the right to make a living remain important issues today, particularly in an agricultural region with limited local industry. “There’s a mindset of people who were here versus those of us who were not,” Snell said. “They say, ‘You may call it your battlefield, but we’re the ones who live here all the time.’ People have been here for generations; they were here before the battle and they feel ownership.”

That changed permanently 148 years ago, and the people back then knew it. Within days, the first sightseers and souvenir hunters were picking their way through the grisly tourist attraction—shoulder to shoulder, almost, with aid society workers and heartbroken families searching for their dead boys. The tussle for Gettysburg’s soul began in these early days, perpetuated by strong-minded individuals in a pattern of conflicting agendas that would set the standard.

A year before the battle, Gettysburg attorney David McConaughy was drawing up plans for a soldier’s cemetery to be incorporated into the town’s Evergreen Cemetery. His problem, as cemeteries go, was a lack of inventory: Only two Gettysburg soldiers had died in the war to date. That problem resolved itself in early July 1863. Now faced with an overwhelming surplus, McConaughy wasted no time in forming the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, which would lay the foundation for what would become the national park.

Meanwhile, another Gettysburg attorney, David Wills, helped initiate a state-based project to collect the dead who were scattered in shallow graves across the battlefield and bury them properly in a central location. But as he set out to purchase appropriate property for the re-interments, he discovered McConaughy had beaten him to the punch at every turn. An angry Wills accused McConaughy of land speculation and profiteering, forcing the governor of Pennsylvania to step in and order mediation so cemetery plans could move forward.

No one was more surprised than Wills when President Abraham Lincoln accepted his invitation to speak at the cemetery’s dedication in November, and for the town this was the point of no return. Thousands descended on Gettysburg once again, and by the time Lincoln had finished uttering his “few appropriate remarks,” the town of 2,400 would never be the same.

By 1880, veterans began returning to Gettysburg to recall past glories and mold the hallowed ground into a lasting shrine bristling with monuments to heroism. They in turn sparked a new interest in the battlefield among non-soldier-tourists who came to see where and how the fighting had taken place. Both veteran and civilian tourists brought with them something that was in high demand at the time: money. The last two decades of the century were good for hotels, restaurants, souvenir shops (walking sticks carved from actual battlefield saplings were the Lincoln refrigerator magnets of their day) and the nascent industry of battlefield guiding.

The line between history and hucksters began to blur. Historical homes became tourist attractions where relics rubbed elbows with souvenirs, refreshments and even a dance hall. But perhaps the first indignant eruption of commerce usurping preservation came courtesy of the Gettysburg Electric Railroad, a six-mile trolley line established in the early 1890s, which touched on, and in some cases defiled, the significant spots on the battlefield’s south end.

Almost immediately the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association cried foul. The administration of President Grover Cleveland voiced its displeasure and a joint resolution of Congress warned of the “imminent danger that portions of the battlefield may be irreparably defaced,” and asked the secretary of war to intervene.

The developers, unimpressed by bureaucratic huffing and puffing, built the line anyway, causing particular damage to the topography of Devil’s Den, the site of a fierce Confederate assault on the second day of the battle. War veterans were outraged—although this didn’t stop many of them from taking advantage of the new and easy transportation.

The developers, unimpressed by bureaucratic huffing and puffing, built the line anyway, causing particular damage to the topography of Devil’s Den, the site of a fierce Confederate assault on the second day of the battle. War veterans were outraged—although this didn’t stop many of them from taking advantage of the new and easy transportation.

The issue wound up in court, with the government suing to condemn the road and the trolley company arguing that plopping plaques along old battle lines was not a critical public mission. The clash went all the way to the top. The U.S. Supreme Court, in a landmark decision embracing the government’s power of eminent domain, ruled against the trolley line in 1896, stating that preservation “seems necessarily not only a public use, but one so closely connected with the welfare of the republic itself as to be within the powers granted Congress by the constitution for the purpose of protecting and preserving the whole country.”

But while the government was allowed to condemn the land, no money was forthcoming to do so, and the trolley continued operations for another decade. When the enterprise was finally shuttered, the automobile had made it largely obsolete.

If commercial enterprises and history were managing an uneasy truce, the Civil War’s centennial shattered the peace. Entrepreneurs saw the potential profits from thousands on thousands of tourists who would rediscover Gettysburg in the early 1960s. That didn’t just pit business against history, it pitted business against business as they jockeyed for prime location. “The question became, where would you start your Gettysburg experience,” said Walt Powell, a former Gettysburg Battlefield Preservation Association chairman. The National Park Service, which had acquired the Gettysburg site in 1933, lost by default, since its offices were upstairs in the town’s post office—there was no official visitor center until 1962. Consequently, commerce springing up on the south side of town and roadside attractions on the Lincoln Highway set the tourists’ agenda.

Tourism at Gettysburg doubled during the 1950s and again in the 1960s. And the main attraction was not necessarily the Peach Orchard and Little Round Top. Gettysburg’s popularity, explained Jim Weeks in his book Gettysburg: Memory, Market, and an American Shrine, was driven by the automobile and the tourist traps that catered to motorized crowds. “Gettysburg changed because American society changed,” he wrote. With those changes came new modes of recreation for anyone heading into Gettysburg and its outskirts. Up went Fort Defiance and Frontier Town, where the Civil War was somehow morphed into battles between cowboys and Indians. Up went Fantasyland, whose take on the Civil War included Santa’s Village, an Enchanted Forest, Rapunzel’s castle, a Wild West fort, petting zoo, puppet show, the Sugar Plum Snack Bar and a 23-foot talking Mother Goose. Kids—in the ’50s and ’60s it was all about the kids—could ride a covered wagon and shoot attacking Indians dead with a Fantasyland-provided popgun.

It was enough to make historians and preservationists see stars. And it feeds their sprawl anxiety to this day. In some of the harsher rhetoric, merchants are said to traffic in “blood money” because they make their living off a great national tragedy. But of course it would be a mistake to assume people of business cannot possess a simultaneous respect for history. Some saw commercialism as a way to make a living off a period they loved.

And the tourist traps were undeniably popular. Even now, message boards dominated by Gettysburg townies wax nostalgic about Fantasyland, which closed in 1980. “I submit that Gettysburg is at an all time low for family friendly,” reads a post on the perpetually peevish (but on occasion, wickedly funny) board called BoroughVENT. “No tower, no Fantasyland, and a huge park that you can’t picnic or play on. Super fun.”

Ah, the tower. The Second Battle of Gettysburg begins in 1971, when Thomas Ottenstein, a wealthy Maryland developer, announced a plan to build a soaring tower on private ground adjacent to the battlefield so tourists, for a small fee, could get a real feel for what the two armies were doing across the landscape. The borough of Gettysburg would get a 10 percent entertainment tax, estimated to contribute $70,000 to the local treasury in the first year. People’s ears perked up. While the national park is a source of pride and profits, its sprawling grounds—as well as nearby lands owned by schools and religious concerns—crowd out other revenue-generating properties. Only 50 percent of the land in Gettysburg is taxable.

But to preservationists and historians the tower was one 307-foot problem. The space-age viewing room atop a lattice of steel girders would dwarf anything on the surrounding landscape and work against the goal of preserving the original views. Although the Park Service, too, was firmly against the tower, the U.S. Interior Department negotiated a deal in which the planned structure would be moved to a slightly less offensive location. In exchange the park would allow an access road. Opponents, still dissatisfied, took the matter to court under a newly passed Pennsylvania referendum designed to protect aesthetic and environmental treasures. They lost, in part, because of Interior’s implicit endorsement in brokering the site exchange.

But to preservationists and historians the tower was one 307-foot problem. The space-age viewing room atop a lattice of steel girders would dwarf anything on the surrounding landscape and work against the goal of preserving the original views. Although the Park Service, too, was firmly against the tower, the U.S. Interior Department negotiated a deal in which the planned structure would be moved to a slightly less offensive location. In exchange the park would allow an access road. Opponents, still dissatisfied, took the matter to court under a newly passed Pennsylvania referendum designed to protect aesthetic and environmental treasures. They lost, in part, because of Interior’s implicit endorsement in brokering the site exchange.

As the tower went up, so did the community’s blood pressure. Next to the National Tower, said Morley Safer in a 60 Minutes investigation, all the other commercialism in town seemed “quietly genteel.” Ottenstein vigorously disagreed. “More people will be turned on to history” because of the appeal of the tower, he argued. His was the only venue where a tourist could get a real sense of the fighting. In fact, Ottenstein liked this educational angle so much, he decided his tower was not entertainment at all, but more of a scholastic venture. This, according to a 1977 editorial in Preservation News, led him to conclude his classroom in the sky was not subject to entertainment tax—causing the project to lose some of its luster with local government.

Not all Gettysburg conflict boils down to commercial versus historic. In the late 1980s a quiet land deal between the Park Service and Gettysburg College reawakened lingering suspicions among preservationists. What initially appeared to be a simple swap would culminate, after years of vitriol, in the halls of Congress.

The deal, as advertised, appeared to be good for the park. It would acquire scenic easement over 47 school-owned acres in exchange for seven acres of parkland for the college to reroute a rail spur away from the campus. But as soon as the swap was accomplished in 1990, the college sent in bulldozers to widen a gentle cut in Seminary Ridge into a canyon-like chute that had to be bolstered with wire cages of stone. Historians and preservationists—who assigned far more weight to the importance of the site as a military feature than did the college—were appalled. Their anger grew over the next three months as excavation continued and the Park Service failed to intervene.

The GBPA sued for $12 million to have the ridge restored to historical accuracy. Representative Mike Synar, an Oklahoma Democrat, called for an investigation. “The college has violated sacred ground,” Synar said on inspecting the site. “They cannot justify what they have done.” During a congressional hearing, the college angrily shot back, contending the whole controversy was “hogwash” and an attempt to gin up public anger over a plot of ground with little historic significance. The suit failed, and the GBPA dryly resolved to make the railroad cut a shrine to government cover-ups.

A new round of dissension broke out at Gettysburg when the Park Service decided in the mid-1990s to build a new visitor center. No one could have disputed the need for a new center—except that some people did. Here, the Park Service’s plan managed to irritate both rank-and-file preservationists, rank-and-file merchants and, for good measure, architects, although this gets ahead of the story.

The old visitor center was in a bad spot, as was the nearby Cyclorama building that housed Paul Philippoteaux’s 19th-century painting-in-the-round of Pickett’s Charge—in fact, it not only depicted the scene of the charge, it was all but sitting smack atop ground that was the object of Confederate strategy. Ideally, these buildings would be destroyed and their contents and operations moved to a less obtrusive location. The money was to come from a public/private partnership. The plan went through several incarnations before the Park Service picked a developer who would build the new facility in exchange for the right to several for-profit operations, including a restaurant and a bookstore/souvenir shop.

Opponents attacked from multiple angles. Merchants were upset that the new center would be built farther away from the town’s commercial strip, and that the park would now be selling the food and souvenirs that fueled their livelihood. A tourist’s point of entry would now obviously be the new visitor center, and this one-stop “mall” might mean travelers would never find their way to Gettysburg’s south-end commercial district.

Preservationists were suspicious. Even the contention that artifacts were decaying due to a lack of proper climate controls at the old visitor center was greeted in some circles as a fear tactic. Upping the ante, opponents suggested that the existing visitor center was filled with asbestos and bulldozing it would release a cloud of cancer-causing fibers.

The developer was eventually dropped as a partner, and in its place came an alliance of battlefield supporters that would become the Gettysburg Foundation, a powerful player in preservation and battlefield interests with an impressive fundraising arm. For some observers, it’s too impressive. Groups that scratch and claw for the financial resources to stay relevant look askance at an organization that, until recently, paid its director a $400,000 salary—an amount that might be commensurate with the job description in the greater executive world, but tends to stun the people of rural Adams County.

The resulting visitor center that opened in 2008 is a charming take on rural Pennsylvania architecture and building materials. Its exhibits are thoughtful, its message powerful and the Philippoteaux painting, which has been refurbished and relocated upstairs, is a critically acclaimed marvel.

Still, there are doubters. Admission has already increased three times since the new center opened. The Foundation has acknowledged the park is operating at a loss and top salaries have been dramatically cut. Aside from the financials, concern remains that a battlefield-preservation group that teams up with the Park Service will lose its ability to be a reliably nonpartisan watchdog.

Charlie Tarbox, owner of Tarbox Toy Soldiers on Gettysburg’s south side, said he was unconvinced of the need for a new center. The Park Service did hold public hearings and provide studies to assess the need, but Tarbox contends it did a “masterful” job of massaging the data to support its plans. As for the center itself, Tarbox said his customers are “split 50-50 between loving it and hating it.” And the same goes for the entrance fees. Curiously, he said, half the people don’t seem to mind them.

Now that the center is open, Tarbox said the effect is noticeable. Foot traffic is down at the businesses that were near the old visitor center. “The restaurants tell me they’ve had a huge falling off,” he said.

The Cyclorama building, however, hasn’t been so easy to get rid of. By 2000, even the much-maligned observation tower had been condemned by the government and came down to the cheers of a sizable crowd. The odd, circular building that once housed the Philippoteaux painting had aesthetically been only slightly more popular than the tower. It seemed too modern and terribly out of place on a Civil War battlefield. Former Park Service Superintendent John Latschar likened it to a big oil drum.

But before the dynamite could be planted, the Park Service learned that new forces were at work in Gettysburg—the Recent Past Preservation Network and the reCyclorama campaign, which believed the building was not a glorified oil drum, but an architectural wonder.

Designed 50 years ago by award-winning architect Richard Neutra, the building indeed has the look of a Texas refinery to the untrained eye. But to professional architects and the Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places, the building is of “exceptional historic and architectural significance.” As if Gettysburg didn’t have enough angles already, the Cyclorama building has pitted preservationist against preservationist based on the age and location of what is to be preserved. The Park Service’s plan to demolish the building has been, temporarily at least, blocked in court, but regardless of the final outcome, the fight seems sure to add another layer of bitterness to the growing strata of conflicts.

Perhaps the greatest source of modern-day angst, however, has been two recent plans for slot machines and casino gambling on the outskirts of town. The most recent campaign had a particularly personal edge to it, given the weakness of the economy and hunger for new jobs. Unlike a marginally profitable fast-food restaurant, or a building where only emotional capital is at stake, gambling raised the promise (or specter) of huge inflows of cash and plentiful work. This wasn’t about the historical appearance of the battlefield, this was—in the eyes of some locals—about putting bread on the table. The historians and preservationists were denying them that right, they believed, and the campaign was angry and intense.

Any potentially commercial project can draw unlikely allies together. Preservationists and commercial interests found themselves sharing concerns about a park-sponsored project when Superintendent Latschar announced that he would head up the Gettysburg Foundation—at a substantial pay raise—after he had helped broker the public/private partnership with the group. Cleared on that issue and subsequently reassigned on other grounds, Latschar has nevertheless retained the admiration of many Gettysburg fans; Civil War scholar Kevin Levin called him “the most important superintendent any NPS battlefield site has had in our lifetime.”

The GBPA itself has not escaped suspicion. Last year, preservationists grew concerned about a report in Civil War News that GBPA meeting minutes reflected discussions of a cash deal with the casino developers in exchange for its support. (Casino developers and current association leaders denied the existence of such a deal.)

And around and around the circle goes.

But despite all the suspicion, intrigue and sometimes anger, Gettysburg the battlefield has not only survived, but flourished. When personalities and noise are factored out, most all groups speak positively about the direction of the battlefield itself—the part that matters—as the Park Service, preservation groups and volunteers work to restore much of its original appearance. And time tends to erase all setbacks. The electric trolleys of a century ago seem quaint. A generation from now, visitors will have to strain to picture the National Tower—once the dominant feature on the battlefield—if they remember it at all. Even with the fate of the Cyclorama building still up in the air, a historically acceptable solution seems inevitable. As large as the conflicts might be, the battlefield is bigger. And the reason it is bigger is that so many people care.

Tim Rowland is a regular contributor to America’s Civil War and the author of the upcoming Strange and Obscure Stories of the Civil War (Skyhorse Publishing, 2011).