In the almost 150 years since she belatedly committed herself to the revolt known as the Indian Mutiny, Lakshmi Bai, the rani (Hindu queen) of Jhansi, has been the only leader to be described in positive terms by her adversaries. True, some reviled her as a villainess, but others admired her as a warrior queen. Indian nationalists of the early 20th century were less divided in venerating her as an early symbol of resistance to British rule.

The future rani was born to a high-caste prominent Brahmin family in Benares (now Varanisi) in northern India on November 19, 1827. Formally named Manikarnika, she was called “Manu” by her parents. Her mother, Bhagirathi, died when she was 4. Under the care of her father, Moropant Tambe, her education included horsemanship, fencing and shooting. In 1842 she became the second wife of Gangadhar Rao Niwalkar, the childless raja of Jhansi, a principality in Bundelkhand.

Renamed Lakshmi Bai, the young rani bore one son in 1851, but he died four months later. In 1853, following a serious illness, Gangadhar Rao adopted a distant cousin named Damodar Rao as his son—similarly, Gangadhar and the brother who had preceded him on the throne were adopted heirs. The adoption papers and a will naming the 5-year-old boy as Rao’s heir and the rani as regent were presented to a Major Ellis, who was serving as an assistant political agent at Jhansi on November 20, 1853. Gangadhar Rao died the following day. Ellis forwarded the information to his superior, Major John Malcolm, a Scottish soldier and the East India company representative in charge of the region, then controlled by Britain’s East India Company. Ellis was sympathetic to the rani’s claims, and even Malcolm, who did not support her regency, described the young widow in a letter to India’s Governor-General James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquess of Dalhousie, as “a woman highly respected and esteemed, and I believe fully capable of doing justice to such a charge.”

Under Lord Dalhousie, the British government had adopted an aggressive policy of annexing Indian states. Charges of mismanagement often offered an excuse. Another justification, applied with increasing frequency after 1848, was the Doctrine of Lapse, which placed any sovereign Indian state as a vassal state under British rule through the East India Company. The British already exercised the right to recognize the monarchical succession in Indian states that were dependent upon them. As a corollary, Dalhousie claimed that if the adoption of an heir to the throne was not ratified by the government, the state would pass by “lapse” to the British.

In spite of the rani’s arguments for the legality of the adoption and Ellis’ statements on her behalf, Dalhousie refused to acknowledge Damodar Rao as Gangadhar Rao’s heir. The new British superintendent, Captain Alexander Skene, took control of Jhansi under the Doctrine of Lapse without opposition. The rani was allowed to keep the town palace as a personal residence and received an annual pension of 5,000 rupees, from which she was expected to pay her husband’s debts. Damodar Rao inherited the raja’s personal estate, but neither his kingdom nor his title.

On December 3, Lakshmi Bai submitted a letter contesting the Doctrine of Lapse with Ellis’ approval, but Malcolm did not forward it. She submitted a second on February 16, 1854. After a consultation with British counsel John Lang, during which she declared “Mera Jhansi nahim dengee” (I will not give up my Jhansi), she submitted yet another petition on April 22, and she continued to resubmit petitions until early 1856. All her appeals were rejected.

Meanwhile, discontent had been building among the Indian soldiers—known as sepoys—within the British East India Company’s army. The General Services Enlistment Act of 1856 required all recruits to go overseas if ordered, an act that would cause a Hindu to lose caste. Rumors spread that the cartridges for the newly issued Enfield rifles were greased with either cow or pig fat, regarded as abominations by the Hindu or Muslim sepoys who would tear them open with their teeth. Assurances that the cartridges were in fact greased with beeswax and vegetable oil were not as effective as rumors of a systematic British effort to undermine the sepoys’ faith and make it easier to convert them to Christianity. In Meerut on May 9, 1857, 85 sepoys who refused to use the Enfield cartridges were tried and put in irons. The next day three regiments stormed the jail, killed the officers and their families and marched on Delhi, 50 miles away. The incident started what became known as the Indian Mutiny.

Thousands of Indians outside the army had grievances of their own against British rule. Reforms against the practice of suttee (the act of a widow throwing herself onto her husband’s funeral pyre) and child marriage, permitting widows to remarry and allowing converts from Hinduism to inherit family property were seen as attacks on Hindu religious law. Land reform in Bengal had displaced many landholders. Violence spread through north and central India as leaders whose power had been threatened by the British took charge and transformed the mutiny into organized resistance.

On June 6, troops at Jhansi mutinied, shot their commanding officers and occupied the Star Fort, where the garrison’s treasury and magazine were stored. The city’s European populace took refuge in the fort under the direction of Captain Skene. The fort was well designed to withstand a siege: It included an internal water supply, but food was limited, and about half of the 66 Europeans were women and children. On June 8, Skene led the British out of the fort, but they were massacred. On June 12, the mutineers left Jhansi for Delhi.

Given Lakshmi Bai’s long-standing grievances against the government, the British were quick to blame the rising in Jhansi on her, but evidence of her involvement was thin. Skene’s deputies and personal servants reported that when the British asked the rani for assistance, she refused to have anything to do with the “British swine.” A Eurasian clerk’s wife who claimed to have escaped from the fort with her children reported that the rani had promised the British safe conduct. Her testimony has since been thoroughly debunked by prominent Indian history S.N. Sen in his thoughtful study titled “1857,” but the idea that she had betrayed the community inflamed British imaginations.

Lakshmi Bai herself sent an account of the massacre to Major Walter Erskine, the commissioner at Sagar and Narbudda, on June 12:

The Govt. forces, stationed at Jhansi, thro’ their faithless, cruelty, and violence, killed all the European Civil and Military officers, the clerks and all their families and the Ranee not being able to assist them for want of Guns, and soldiers as she had only 100 or 50 people engaged in guarding her house she could render them no aid, which she very much regrets. That they, the mutineers, afterwards behaved with much violence against herself and her servants, and extorted a great deal of money from her….That her dependence was entirely on the British authorities who met with such a misfortune the Sepoys knowing her to be quite helpless sent me messages […]to the effect that if she, at all hesitated to comply with their requests, they would blow up her palace with guns. Taking into consideration her position she was obliged to consent to all the requests made and put up with a great deal of annoyance, and had to pay large sums in property as well as cash to save her life and honour. Knowing that no British officers had been spared in the whole District, she was, in consideration of the welfare and protection of the people, and the District, induced to address Perwannahs to all the Govt. subordinate Agency in the shape of Police, etc. to remain at their posts and perform their duties as usual, she is in continual dread of her life and that of the inhabitants. It was proper that the report of all this should have been made immediately, but the disaffected allowed her no opportunity for so doing. As they have this day proceeded towards Delhi, she loses no time in writing.

In a subsequent letter, the rani reported there was anarchy and asked for orders from the British. Erskine forwarded both letters to Calcutta with a note saying her account agreed with what he knew from other sources. He authorized the rani to manage the district until he could send soldiers to restore order.

Faced with attacks by both neighboring principalities and a distant claimant to the throne of Jhansi, Lakshmi Bai recruited an army, strengthened the city’s defenses and formed alliances with the rebel rajas of neighboring Banpur and Shargarh. Her new recruits included mutineers from the Jhansi garrison.

The positive assessment of local British officials was not enough to overcome the British belief in Calcutta that Lakshmi Bai was responsible for the mutiny and the massacre. Her subsequent efforts to defend Jhansi confirmed their beliefs. In January 1858, Major General Sir Hugh Rose marched toward the city. As late as February, the rani told her advisers that she would return the district to the British when they arrived.

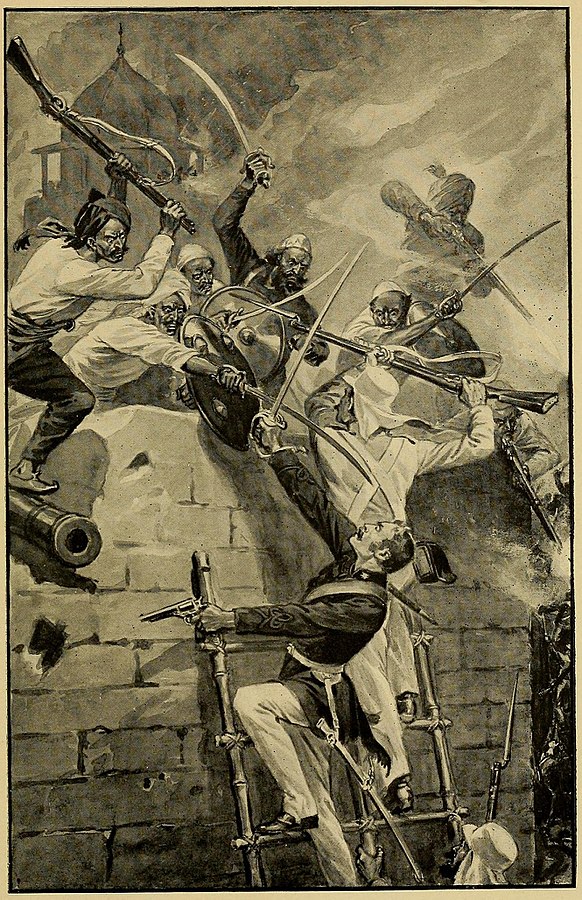

On March 25, Rose laid siege to Jhansi. Threatened with execution if captured by the British, Lakshmi Bai resisted. In spite of a vigorous defense, by March 30, most of the rani’s guns had been disabled and the fort’s walls breached. On April 3, the British broke into the city, took the palace and stormed the fort.

The night before the final assault, Lakshmi Bai lashed her 10-year-old adopted son to her back and, with four followers, escaped from the fortress. Her father was less fortunate. He was captured and summarily hanged by the British, who sacked Jhansi for the next three days. After riding some 93 miles in 24 hours, Lakshmi Bai and her small retinue reached the fortress of Kalpi, where they joined three resistance leaders who had become infamous in British eyes for the atrocity at Cawnpore: Nana Sahib, Rao Sahib and Tatia Tope. The rebel army met the British at Koonch on May 6 but was forced to retreat to Kalpi, where it was defeated again on May 22-23.

On May 30, the retreating rebels reached Gwalior, which controlled both India’s major thoroughfare, the integral Grand Trunk Road, and the telegraph lines between Agra and Bombay. Jayaji Rao Scindhia, the maharaja (grand ruler) of Gwalior, who had remained loyal to the British, tried to stop the insurgents, but his troops went over to their side on June 1, forcing him to flee to Agra.

On June 16, Rose’s forces closed in on Gwalior. At the request of the other rebel leaders, Lakshmi Bai led what remained of her Jhansi contingent out to stop them. On the second day of the fighting at Kotah-ki-Serai, the rani, dressed in male attire, was shot from her horse and killed. Gwalior fell soon after, and organized resistance collapsed. Resistance leaders Rao Sahib and Tatia Tope continued to lead guerrilla attacks against the British until they were captured and executed. Nana Sahib disappeared and became a source of legend.

British newspapers proclaimed Lakshmi Bai the “Jezebel of India,” but Sir Hugh Rose compared his fallen adversary to Joan of Arc. Reporting her death to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, he said: “The Rani is remarkable for her bravery, cleverness, and perseverance; her generosity to her subordinates was unbounded. These qualities, combined with her rank, rendered her the most dangerous of all the rebel leaders.”

In modern India, Lakshmi Bai is regarded as a national heroine. Statues of her stand guard over Jhansi and Gwalior. Her story has been told in ballads, novels, movies and the Indian equivalent of Classics Illustrated comics. Prime Minister Indira Ghandi appeared as Lakshmi Bai in a political commercial in the 1980s.

“Although she was a lady,” Rose wrote, “she was the bravest and best military leader of the rebels. A man among the mutineers.” His praise is echoed in the most popular of the folk songs about her: “How well like a man fought the Rani of Jhansi! How valiantly and well!”

This article was written by Pamela D. Toler and originally published in the September 2006 issue of Military History magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Military History magazine today!