The year was 1879, and while the Lincoln County War was over, central New Mexico Territory still bore scars from the violence of that factional conflict. No longer welcome in the embattled county seat of Lincoln, hard cases like Billy the Kid, pals Tom O’Folliard and Billy Wilson, and latecomer “Dirty Dave” Rudabaugh had to find new haunts in which to hang their hats. While several shady locales appealed to such fugitives, perhaps none checked the boxes as thoroughly as the mining camp of White Oaks.

That fall partners John Wilson, Jack Winters and George Baxter were prospecting for gold in the Jicarilla Mountains little over a mile west of where White Oaks would soon sprout. As the story goes, Wilson was out for a stroll after supper when he happened across an outcrop containing gold. Some say Wilson himself was a fugitive at the time of his lucky strike. That would certainly account for his decision to sell out to his partners that very afternoon for $40, a pony and a bottle of whiskey. Wilson’s North Homestake claim ended up being worth a half million dollars.

With the discovery of gold in what became known as Baxter Gulch, miners rushed in by the hundreds, intent on finding easy riches. Residents named the tent city that sprang up after white oaks that thrived on the brim of a local spring. In his memoirs White Oaks pioneer Morris B. Parker, who arrived in camp in 1880, recalled the nascent settlement:

These were the embryonic days of White Oaks, and they were no doubt full of fun, tragedy and disappointment—local history in the making.…I was too young to be greatly impressed by such matters. Nevertheless, the mixed character and culture of the residents, both mobile and fixed, was evident. They ranged from ignorant nomads—cowboys and prospectors—to college graduates. They included good men and bad, gold-hungry adventurers and people who just came to look around.

Within two years more than a dozen gold mines were in operation. The most profitable and enduring were the North and South Homestake and the Old Abe. By the turn of the century gold production at the White Oaks District totaled $3 million.

Unlike the ephemeral tides of fortune, however, White Oaks’ founders intended for their town to endure and from its inception envisioned a community offering the finer things. Thus it grew rapidly in the 1880s, attracting a civilized Eastern population as had no other town in the Southwest. In October 1882 surveyors plotted the townsite, on an 80-acre rectangular patch of land, and the U.S. Land Office signed off in May 1883. Its cornerstones remain firmly embedded in the hard earth. By 1888 White Oaks boasted 1,000 residents who availed themselves of everything from a private educational academy to an opera house. Its first newspaper, the White Oaks Golden Era, fired up its presses in December 1880, while the Lincoln County Leader put out its first edition on Oct. 21, 1882, and published weekly until Dec 2, 1893. They were the largest papers in the region outside of The Las Vegas Gazette, published nearly 130 miles to the north.

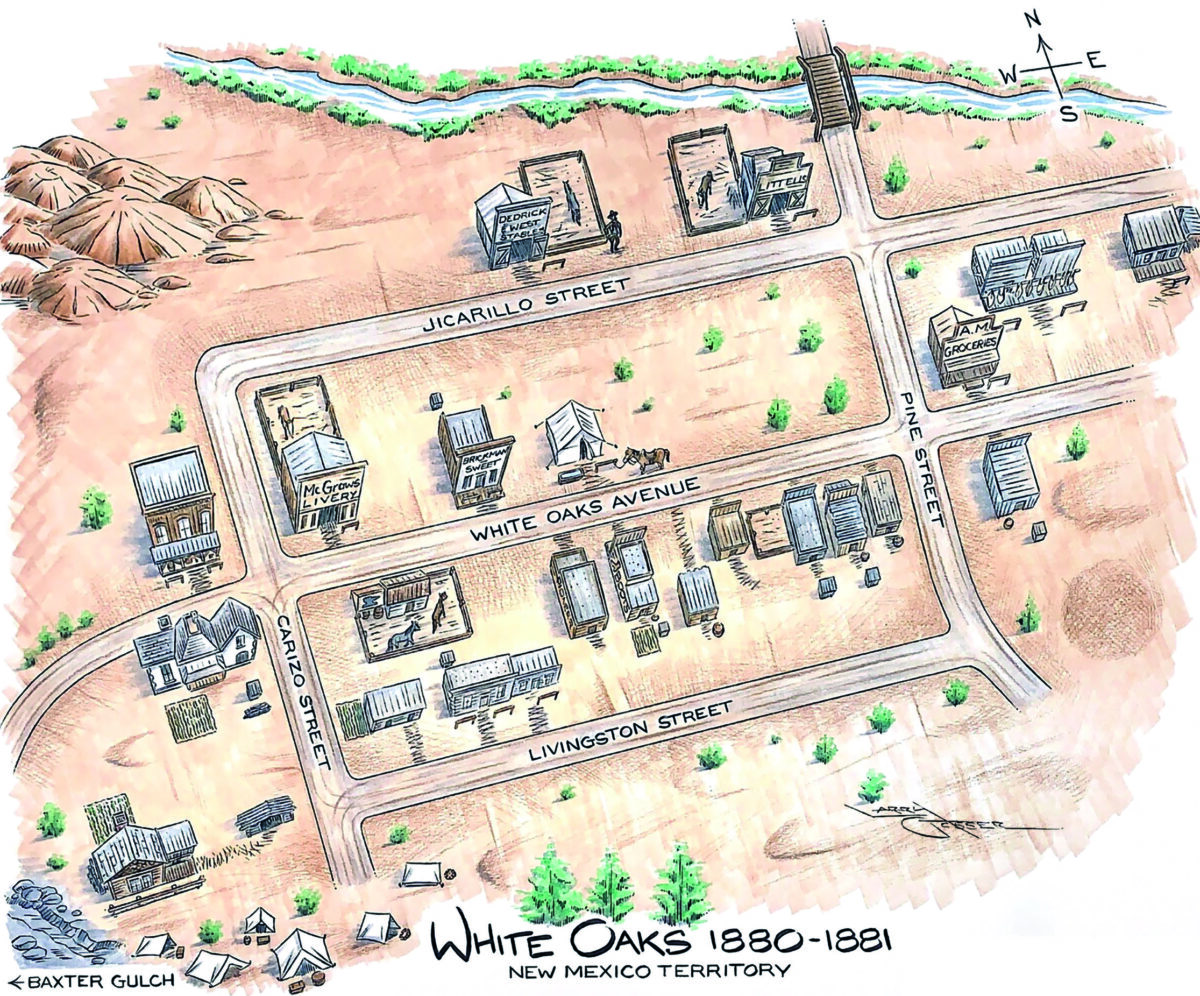

As the founders of White Oaks took the time to have their town properly surveyed and plotted, much of its structure and design was recorded through extant tax and property records. Still, a clear picture of its early years has been lacking. For one, while the mining camp may have experienced a formal upbringing, it had a rough and violent start. Between 1879 and ’84 it was not a place for the faint of heart.

Not just any town could attract the likes of Billy the Kid, yet he and his gang became familiar figures in White Oaks as they hurrahed about its dusty streets. The West & Dedrick livery stable provided them a place to sell livestock stolen from ranches as far south as Tularosa and north to Puerto de Luna. The stable also served as a haven of sorts when things got too hot.

Its half dozen saloons welcomed Billy and his outlaw pals with their gambling tables and women of ill repute. Of note was the Pioneer, a showplace at the heart of the town. George Curry (who later served a term as territorial governor of New Mexico) recalled it as “a palace of lights, mirrors, and boasting a long mahogany bar.” A tongue-in-cheek retrospective article in The Albuquerque Tribune stated, “Proprietors of the Pioneer saloon sold three different grades of whiskey at three different prices—all of it taken from the same barrel.” The Pioneer was likely where attorney Ira Leonard stayed in 1880 while representing Billy the Kid, perhaps sharing a beer with the Kid while ironing out the details of the pardon Billy felt Territorial Governor Lew Wallace owed him. Leonard was one of the attorneys who later defended the Kid at the latter’s murder trial in Mesilla, New Mexico Territory.

On the evening of Nov. 23, 1880, Lincoln County Deputy Sheriff Jim Redman, a part owner in the Pioneer, was sitting on the saloon’s front porch when the Kid, Billy Wilson and Rudabaugh rode by, and Billy took a potshot at him. Redman happened to be a friend of the Kid’s pal O’Folliard, so it is likely Billy only fired the shot as a warning. The prior evening the outlaw trio had gotten into a shootout at Coyote Spring, north of town, with a posse joined by Redman and led by his saloon partner and fellow deputy Will Hudgens. It was also at the Pioneer—two months after the Kid’s infamous April 28, 1881, escape from the Lincoln County Courthouse—someone tipped off Deputy John W. Poe that Billy was laying low in Fort Sumner. Weeks later, on July 14, Sheriff Pat Garrett would gun down the Kid.

The Pioneer was hardly the only lively spot at “the Oaks,” as residents nicknamed the town. Its abundance of tent saloons, dance halls, gambling houses and billiard halls attracted a range of Westerners, from honest citizens looking for a bit of fun to hard cases looking to blow off steam. Given the prevalence of ranches in and around Lincoln County, the Oaks became a gathering point for cattle rustlers. It was also the site of a counterfeit ring run simultaneously out of the West & Dedrick stable by William H. “Harvey” West and brothers Sam, Dan and Mose Dedrick. That double duty would be the undoing of the partners in crime.

In early 1880 West and partner Sam Dedrick passed $400 in counterfeit bills to purchase the stables from Kid cohort Billy Wilson. Unaware the bills were counterfeit, Wilson put them into circulation, soon attracting the attention of the feds. When the Secret Service appointed Special Operative Azariah Wild to investigate the matter, the Dedrick brothers wisely fled. That December at Stinking Springs, far to the northwest, Garrett and posse would catch up to Wilson. Ultimately convicted in March 1882 of passing counterfeit bills, he was sentenced to seven years in prison. However, Wilson escaped the Santa Fe jail before he could be transported to a federal prison in Missouri.

There was too much opportunity and money to be made legally in White Oaks for the town to have remained unruly long. Among the leading citizens who had high hopes for the growing community were Dr. Alexander G. Lane and Judge Franklin Houston “Frank” Lea.

Dr. Lane arrived in White Oaks in May 1880 to open a drugstore and soon took up mining, an interest he pursued for the remainder of his life. He served as the town’s first treasurer and built an impressive two-story home that doubled as his office. Before a school was set up in White Oaks, the doctor taught local children in the living room of his house.

Among the earliest settlers in White Oaks, Judge Lea was instrumental in the founding and organization of the town. He helped build the first hotel, White Oaks House, and ran a grocery and trade store on the west side of town. Though he had ridden with William Quantrill’s pro-Confederate bushwhackers during the Civil War, Lea served respectably as justice of the peace in the Oaks’ early years.

Among the notorious defendants to appear before Judge Lea was “Whiskey Jim” Greathouse, who owned a large ranch a few miles north of White Oaks and often bought stolen livestock from Billy the Kid and cohorts. On Nov. 27, 1880, four days after having taken a potshot at Deputy Redman in White Oaks, Billy holed up with Wilson and Rudabaugh at the Greathouse ranch. When a posse tried to flush them out, Deputy Jimmy Carlyle was killed in the crossfire. In March 1881 Lea arraigned Greathouse as an accessory to murder. Though he escaped prosecution on that charge and started a successful freighting business, the rancher maintained a sideline buying and selling butchered beef from rustlers.

Despite White Oaks’ increasing prosperity and influential citizenry, its potential for growth had limits. In that era few towns of any size could survive independent of a railroad, and White Oaks proved no exception. As production at the mines slowed in the late 1880s, the need to lure a railroad to town took on increased urgency. Alas, it wasn’t meant to be. According to oft-repeated rumors, the approaching El Paso & Northeastern Railroad bypassed White Oaks due to the greed of town fathers who had supposedly hiked land prices and then smugly waited for EP&NE executives to pay their inflated prices. No extant period documentation supports this claim. To the contrary, in December 1892 the Lincoln County Leader reported that townspeople stood ready to pay a subscription fee of $50,000 in the form of bonds payable to the railroad’s principal financier, James Gould. Twenty-one leading citizens had contributed $24,500 and were confident they could raise the balance, thus ensuring the arrival of the railroad and survival of White Oaks, whose population had peaked at more than 2,000 souls.

In the meantime, cruel fate intervened. On December 2, amid negotiations, word reached White Oaks that Gould had died at home of tuberculosis. Eight days later Lincoln County Leader editor William Caffrey wrote a less than flattering farewell to the magnate:

Jay Gould Dead

On Friday of last week the name of Jay Gould was expunged from off of the page of life, and his soul went out to meet the Maker of rich and poor.

For many years the “Little Wizard” has been recognized as the Napoléon of finance in this country.…However much men may have envied him in the past, the present holds no one who’d care to share his couch. His name, here, is now no more talismanic than that of a pauper. He has gone where there are no class distinctions, where all are clothed alike and titles are unknown.

In the wake of these disparaging remarks the town of White Oaks died with Gould. Prior to the financier’s death the route survey had been completed and secured, the land for the depot held, and the right of way secured. But in the wake of Gould’s death the EP&NE bypassed White Oaks for the whistle stop of Carrizozo, 12 miles to the southwest. Whether Caffrey’s callous comments had triggered the reversal is uncertain.

District mines continued production into the early 1900s, but by then White Oaks’ promising shimmer had faded and the population plummeted. By mid-century only a handful of holdouts remained. Among them was Susan McSween Barber, the widow of Lincoln County War victim Alexander McSween, who’d rebounded to become the “Cattle Queen of New Mexico.” She lived in a small house on the north side of town until her death at age 85 in 1931.

In 1970 the National Register of Historic Places recognized White Oaks as a historic district. Today it’s home to a handful of residents, scattered period buildings, a volunteer fire department, a Vietnam memorial and a few businesses, including the No Scum Allowed Saloon. South of town is Cedarvale Cemetery, whose internees include McSween Barber and James W. Bell, the younger of two Lincoln County deputies (the other being Bob Olinger) slain by Billy the Kid during the latter’s infamous April 28, 1881, jailbreak from the county courthouse in Lincoln. Such men and women deserve to be remembered, as does White Oaks.