As they mustered for battle in the Valley of Elah, the armies of Israel knew disaster awaited.

Their war against the Philistines was going badly, and no Israelite would stand up to the enemy champion, a mighty armored giant. Finally, a young shepherd answered the call. His brave action gave the world a new phrase to describe a fight against hopeless odds: “David and Goliath.”

World War II generated a classic example: the Winter War. In November 1939, the Soviet Union—with a Red Army numbering in the millions of men, tens of thousands of tanks, and thousands of aircraft—invaded tiny Finland, a third-rate power whose military force was less than a tenth as large. World War II was a deadly environment for smaller nations, with the Great Powers wiping them off the map at will. Finland was one small power that said “no.” The Finns fought back, leaving a legacy of heroism that persists to the present.

Like David of old, Finland went up against a giant and stared death in the face. That fight showed what a determined people could achieve even in the most desperate circumstances. The Winter War reminded the world that it was better to go down swinging than to submit to injustice. The Finns’ stand is why the Winter War mattered in 1939, and why it always will.

The Soviet-Finnish conflict began in that strange interlude during World War II known as the “Phony War.” The Germans had invaded and overrun Poland in September 1939, leading Britain and France to declare war on the Third Reich. And then, for six months, nada. The Germans were conflicted about how to proceed, with Hitler demanding an immediate offensive in the West and most of his officer corps demurring. Although the German army had beaten Poland with ease, it had been uncertain at times and unsteady under fire. That performance left German commanders underwhelmed, and destined the Wehrmacht for a winter spent in rigorous training, honing its edge and learning techniques for combined arms warfare. The Allies reverted to World War I mode, trying to strangle Germany’s economy with a naval blockade, a tactic that would take years. The combination resulted in inaction on all fronts.

Actually, not all. One great power was ready to march. In August 1939, the Soviet Union had signed an agreement with the Reich not to attack one another. The Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact had shocked the world, as mortal enemies embraced and drank hearty toasts to each other’s health. It was the factor that allowed Hitler to invade Poland the next month without having to worry about a prolonged war on two fronts.

The pact also contained a secret protocol dividing Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence. Here was a classic example of power politics, with the strong taking what they wanted and the weak having to pay the price. The Germans were to get primacy in Western Poland, “in the event of a territorial and political rearrangement of the areas belonging to the Polish state”—that is, once they had destroyed Poland. The Soviets got much more territory: the province of Bessarabia (then part of Romania, today independent Moldova); the eastern half of Poland (the Kresy, or “borderlands” region); the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia; and Finland. Essentially, the protocol reimposed the borders of the old Tsarist Empire, entitling Joseph Stalin to territories that had broken away from Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

And now it was time to cash in. Through foreign minister and henchman Vyacheslav M. Molotov, Stalin began to put the screws to Finland, a sprawling but sparsely populated land Russia had controlled from 1809 to 1917. On the surface, the demands on the young nation seemed moderate enough. The Soviets wanted to lease the Hanko Peninsula on Finland’s southern coast for use as a naval base. And they wanted to push back the border on the Karelian Isthmus, only 20 miles from the great Soviet metropolis of Leningrad. Molotov also declared Stalin’s willingness to cede lands in adjoining Soviet Karelia amounting to twice the territory demanded of Finland. In other words, the Soviets promised to give Finland more land than they were taking away.

The Finns, however, saw not negotiation but ultimatum. This was the era, after all, of Hitler and Benito Mussolini and Imperial Japan, of lawlessness in the international arena, of the stronger preying on the weaker. The Finns knew that ceding any territory to their former imperial masters would threaten their independence. Soviet demands gave way to threats, and when the talks faltered, Molotov had the last word: “Since we civilians don’t seem to be making any progress, maybe it’s the soldiers’ turn to speak.”

And just like that, the world had another war on its hands. On November 30, 1939, the big guns roared, Soviet bombers screamed overhead, and the Red Army invaded Finland. What Finns called the Talvisota (“Winter War”) had begun.

The Soviets must have been confident of a rapid, decisive victory. Only months earlier, German panzer columns had sliced through Polish defenders in multiple sectors, linking up far behind the lines and encircling virtually all of Poland’s million-man army. The Poles had fought bravely, even heroically in most cases, but were simply outclassed. It was a result typical of a clash between a strong power and a smaller, weaker neighbor, and no doubt what Stalin, Molotov, and Soviet commanders expected on the Finnish front.

What they got was very different. The Soviets had numerical and material superiority on the ground—even greater in the air—and their round-the-clock bombing of Helsinki and other targets had inflicted heavy civilian casualties, but the first month of the conflict defined the term “military disaster.” The Red Army got nowhere and suffered mass casualties in doing so.

Some of it was Stalin’s fault. In response to the darkening international situation, he enlarged the Soviet military—expanding the Red Army between 1937 and 1939 from 1,500,000 men to around 3,000,000—but he also simultaneously and bloodily purged the army’s leadership, accusing some 75 percent of his army, corps, and divisional commanders of disloyalty. Many would wind up imprisoned or shot. The combination left masses of poorly trained soldiers serving under officers who were political hacks or scared to death of exercising initiative for fear of running afoul of Stalin and his secret police.

Stalin had also not counted on the Finns to fight—and fight well. Commanding the Finnish army was the wily Marshal Carl Gustaf Mannerheim. Tall, handsome, and refined, he was the scion of Swedish nobility who had settled in Finland in the late 1700s; though multilingual, Mannerheim never became particularly adept at speaking Finnish. Born a subject of the Tsar, he entered the Russian army and rose to the rank of Lieutenant General. After the Tsar’s overthrow in February 1917 and the Bolshevik Revolution that October, the Grand Duchy of Finland declared independence. In the almost four-month civil war that followed, Mannerheim successfully led the “White” faction against the pro-Bolshevik “Reds.” He served briefly as the new state’s regent, chaired Finland’s Defense Council, and, at 72, came out of retirement to fight the Russians.

Coolly sizing up the situation, Mannerheim recognized that he would have to wage two wars. He had no choice but to deploy most of the regular army—six of nine small divisions—on the southern frontier opposite Leningrad. That 90-mile front spanned the Karelian Isthmus between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga. There the marshal constructed an interlocking system of tank traps, trenches, machine-gun nests, and armored bunkers that became known as the Mannerheim Line and sat patiently, waiting for the Soviets. When the Soviet 7th Army, under theater commander General Kirill A. Meretskov, lumbered forward in clumsy frontal assaults, the Finns shot them to pieces.

Meretskov was one of those generals who had risen by virtue of the purges. While he would go on to a reasonably successful wartime career, in late 1939 he certainly wasn’t ready for army command. He planned sloppily, hastily deploying assault divisions drawn from the relatively temperate Ukrainian Military District. These troops were neither conditioned nor equipped for the frigid north and its thick forests, and Meretskov knew little about the Finnish forces, their defensive preparations, or even the terrain over which he had to fight. The general’s campaign was, one historian later wrote, an example of “organizational incompetence” from top to bottom.

Haphazard planning led to battlefield disaster. After a perfunctory artillery bombardment, 7th Army assault troops charged. But their rounds had negligible effect. The Finns, hunkered in protected bunkers, managed to reach their machine guns in plenty of time to meet—and slaughter—the attacking infantry. Soviet reinforcements were late getting to the front, and almost always went where the Finns were holding up the attack, rather than where the Red Army was making headway. Piling more soldiers into killing grounds of Finnish fire only multiplied Soviet casualties.

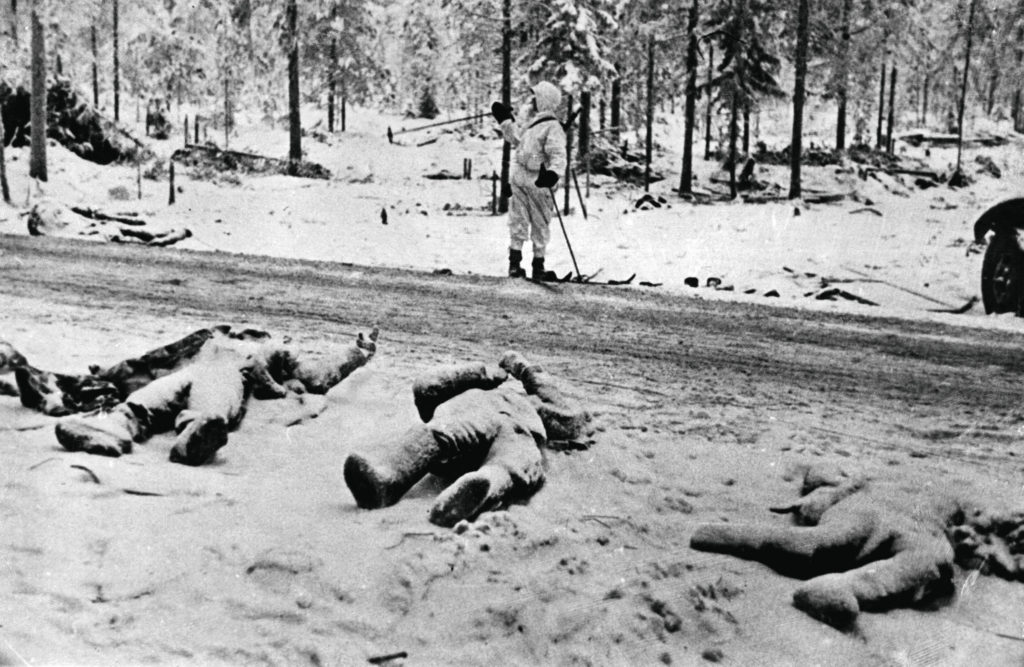

Up north, Mannerheim had to conduct a very different kind of war. With nearly 600 miles of border and nowhere near enough regular divisions to cover them, he relied upon the Home Guard as the backbone of his defense. These were independent battalions of hardy citizen soldiers, dead shots who knew every inch of the land and were accustomed to the cold. Virtually all Finns could ski, but the Home Guard specialized in fighting on skis, gliding silently out of the forest, nearly invisible in long white parkas and hoods, to rake a ponderous Soviet column with fire from their viciously effective KP/-31 submachine guns, and then vanish back into the trees.

The Guard preferred soft targets with high impact, like field kitchens and supply wagons, but guardsmen also fashioned crude gasoline bombs that worked well against Soviet tanks. First used in the Spanish Civil War, these “Molotov cocktails,” as the Finns called them, were a true poor man’s weapon, and the forerunner of today’s improvised explosive devices (IEDs). While that weaponry might have been primitive, the Finns made up for it with intestinal fortitude, bravery, and grim determination. They call it sisu—“guts.”

As badly as the Soviets’ drive against the Mannerheim Line had gone, they faced something much worse in the north. In the forests near Suomussalmi, a village astride the route through the narrow waist of central Finland, a reinforced brigade of Home Guardsmen ambushed, trapped, and largely destroyed two entire Soviet divisions, the 44th and 163rd. At the village of Tolvajärvi, north of Lake Ladoga, two more invading divisions, the 139th and 75th, suffered the same fate.

In both battles, roadblocks stalled the attackers long enough for highly mobile ski formations to get around their flanks and into their rear. By Christmas, the defenders had broken invading columns into isolated, immobile fragments. The Finns called the starving, freezing, surrounded invaders motti—sticks bundled for firewood and left to be picked up later. For the Soviets it was an operational debacle of the first magnitude, made worse by arctic weather. In their plight, Red Army men turned to a traditional remedy. “They started giving us 100 grams of vodka a day,” one of them wrote. “It warmed and cheered us during frosts, and it made us not care in combat.”

Soviet soldiers fought unflinchingly, whether charging the Mannerheim Line or holding on grimly in their motti positions, but losses soon reached the hundreds of thousands. One Finnish sniper, Simo Häyhä, was responsible for 505 of them. In civilian life a farmer and a prize-winning marksman, Häyhä kept to himself and rarely said a word as he went about his grim business. The Russians nicknamed him “White Death”—a name that suited the entire Finnish army in this period of the war.

By the end of December, the Finns seemed to have won the Winter War. They had stood tall and smashed the invaders. Global opinion rallied to their cause, especially in the democratic West, where the Finns had become world celebrities—good democrats “fighting with the heroic loyalty characteristic of a free people when its liberty is at stake,” as the Times of London put it. The League of Nations had meanwhile expelled the Soviet Union on December 14.

The British and French governments were actually considering sending aid to Finland, perhaps even an expeditionary force, to fight the Soviets. (They didn’t, which was probably for the best. Such a move would have made the Soviet Union and Germany true brothers in arms, allied against Britain and France—with almost unimaginable consequences.) In the United States, former president Herbert Hoover formed a Finnish Relief Fund to aid the beleaguered nation’s civilians and refugees. Within two months, the charity raised $2,000,000. Volunteers the world over—from the United States and Canada, and from Hungary, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden—tried to book passage to Finland to fight in the war, much as others had flocked to Spain to fight just three years before.

And yet, even amid Finland’s seeming triumph, the military situation was eroding. In the Bible, David slew Goliath, but in this frozen Valley of Elah, Goliath was still standing. Mannerheim’s forces had no way to carry the war into Russia, and thus no sword to slay their enemy. The Finns had staggered the Red Army, but the Soviet Union remained an immense and wealthy country with impressive powers of recuperation. And in war, bigger battalions often find a way to reassert themselves— no matter how serious their early defeats or how righteous the cause of the underdog. Most often David doesn’t win.

The first days of 1940 saw the tide turn quickly, when Stalin named one of his bright young officers, General Semyon K. Timoshenko, to command in the theater. The new supremo, 44, was a vigorous, hard-headed leader who took a sober view of things. Yes, the opening of the war had been a disaster, but Timoshenko knew the Red Army still had the reserves to beat Finland. All it needed was a firm hand and better planning. Stalin kicked Meretskov downstairs to command the 7th Army alone; another army, the 13th, under General Vladimir. D. Grondahl, arrived alongside him.

Timoshenko spent January in careful preparation, weeding out inefficient or incompetent commanders, and drilling his troops in assault tactics. When he had tuned the army to his satisfaction, he chose what a military analyst might call the obvious solution. He suspended the fruitless fight in the north and launched a coordinated two-army assault against the Mannerheim Line, with the 7th Army on the left and the 13th on the right. The assault involved 600,000 men, arrayed in four echelons, with lavish air and artillery support.

The Soviets again endured stupendous losses, but the Finns could not match such numbers, and neither could the Mannerheim Line. Timoshenko also showed a great deal of finesse, launching elements of his XXVIII Rifle Corps across the frozen Gulf of Finland toward the key port at Finland’s second-largest city, Viipuri. The appearance of major Soviet forces deep on the Finns’ right flank and rear did what had seemed impossible: it helped force the Finns out of the Mannerheim Line.

The assault opened on February 1, 1940, and cracked the Line by the 11th. Three weeks later, Viipuri was in Soviet hands, as was the main road from Viipuri to Helsinki. By now, the defenders had suffered nearly 70,000 casualties: not a staggering figure—unless your population is only four million. Blasted out of their one solid defensive position, the Finns had no choice but to ask for terms.

The Soviets had won the Winter War and, in the subsequent Moscow Peace Treaty, took much more than they had originally demanded. Finland had to cede Viipuri and the northern port of Petsamo, along with the entire Karelian Isthmus. All told, Finland lost some 11 percent of its original territory. But victory had come at great cost to the Soviets. Nikita Khrushchev later placed the casualty figure at an even one million. “All of us,” he wrote, “sensed in our victory a defeat by the Finns.” Khrushchev’s tally was almost certainly inflated, part of his effort as Soviet Premier to discredit the Stalinist regime, but the reality was bad enough: somewhere between 400,000 and 600,000 total casualties, with 120,000 to 200,000 killed in action—many times the number of men in the entire Finnish army at the start of hostilities. Whatever the true figure, the Soviet Union paid a steep price for what was, in the end, a border rectification.

The Winter War presented a dual face to the world. Phase one featured the Red Army carrying out some of the clumsiest, most inept frontal assaults imaginable. “They chose to throw people chest first into the machine-gun and artillery fire of pillboxes, in bright sunny days,” as one participant put it. Phase two offered a contrary image: youthful and gifted Soviet commanders with a solid grasp of high-intensity combined arms operations, skillfully employing a huge, well-supplied force and crushing an enemy that had, a few weeks earlier, seemed invulnerable. Only time would tell which was the real Red Army.

Learning the lessons of a war has never been an exact science, and observers at the time drew contradictory conclusions. Many analysts saw their notions of Soviet military incompetence confirmed. Precisely because of its David-and-Goliath character, the Winter War’s opening phase drew worldwide attention. The image of those nimble ski troops slashing into a lumbering adversary was simply irresistible. Certainly Hitler and the German General Staff, imagining an invasion of the Soviet Union, looked at the Winter War and pictured a pushover. Perhaps they all should have paid more attention to the more conventional end of the fighting: to Goliath’s rebound, to Timoshenko’s war.

The Soviets, too, had blind spots. To their credit, they realized that the war had been a fiasco. On the debit side, they made the common mistake of overreacting. In the 1930s, the Red Army had been at the forefront of experimentation with high-tempo mechanized warfare. In the wake of the Winter War, the Red Army returned to basics: reconnaissance, security and concealment of columns on the march, carefully phased attacks. Soviet military literature from just after the Winter War showed a force obsessed with the minutiae of battle in cold climates: which gear to use crossing deep snow in a tank, the importance of rapid first aid in extreme cold, preparation of ski trails. Soviet doctrine of that period no longer emphasized deep strikes utilizing masses of armor, but “overcoming the enemy’s long term defenses” and “patiently gnawing through breaches in the enemy’s fortifications.” According to one young commander, the new doctrine was more like “engineering science” than the art of operations or maneuver. But the spring of 1940 was the worst time to be thinking slow and small, as the German invasion in 1941 would prove.

Finally, what of the Finns? They were the global heroes of 1939-40, and the savage fight they put up probably made the difference between losing border territories and being annexed and occupied by Soviet forces. Unfortunately for them, a desire to win back lost territories led to a classic wrong turn. The Finns rearmed as feverishly as their tiny economy would allow. They embarked on a policy of close military cooperation with Germany—never formally joining the Axis, but going so far as to allow Hitler to station troops on Finnish soil.

On June 25, 1941, three days after the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa, Finnish forces invaded the Soviet Union. This was the Jatkosota, the “Continuation War”—far less the stuff of epic, with minimal gains, heavy losses, and, after a massive Soviet offensive into Finland in June 1944, a hasty exit from the war. Finland was no longer a hero in the West—it now appeared to be just another one of Hitler’s lackey states. Yet even in defeat the Finns managed to preserve their independence. They experienced neither a bloody Soviet-style “liberation,” nor the agony of Italy, first occupied by its erstwhile Axis ally, then destroyed in the course of heavy fighting.

Still, the Winter War was a signal moment. The long-term aim of World War II was the defense of the weak against the strong: Poland versus Germany, China against Japan, Greece versus Italy. The era’s dictators thought they could laugh at international law, but eventually they all learned to stop laughing. The Winter War was a David-and-Goliath tale that invited contempt for bullying and aggression. The Soviets won territory; the Finns, the admiration of the world.

In that sense, the loser won.

Originally published in the August 2014 issue of World War II. To subscribe, click here.