As it fought to defeat a revolution declared by its American colonies, Britain also was at war by proxy on the Indian subcontinent. Troops of the British East India Company, a royally commissioned private enterprise combining the functions of business, government, and military conquest and occupation, were on the march half a world away. Similar entities were operating on the crown’s behalf in locales around the world.

The British East India Company, established in 1600 to trade in spices, tea, cotton, indigo, silks, and other commodities, arrived in India in the early 1600s and slowly penetrated promising markets, becoming influential in local politics. A major boost for the Company came in 1757 when its military forces, composed of Indian mercenaries called sepoys trained in European style fighting, defeated those of Bengal ruler Nawab Siraj ud Daula, at the village of Plassey. In subsequent victories the Company outwitted and outfought local rulers using superior military tactics and modern infantry. Installing indigenous puppet figures at the helms of conquered provinces, the Company acquired the right of revenue collection. The Company’s chief stock in trade became imperialism, imposed on conquered districts as a means of extending a British empire on which, it was said, “the sun never set.” Having subjugated populaces led by illustrious Indians such as Siraj ud Daula, the last nawab of Bengal, the Company turned its attention to South India and the Kingdom of Mysore, which controlled a vast triangular region at the toe of the subcontinent, the Deccan peninsula. Mysore resisted, leading to a series of wars.

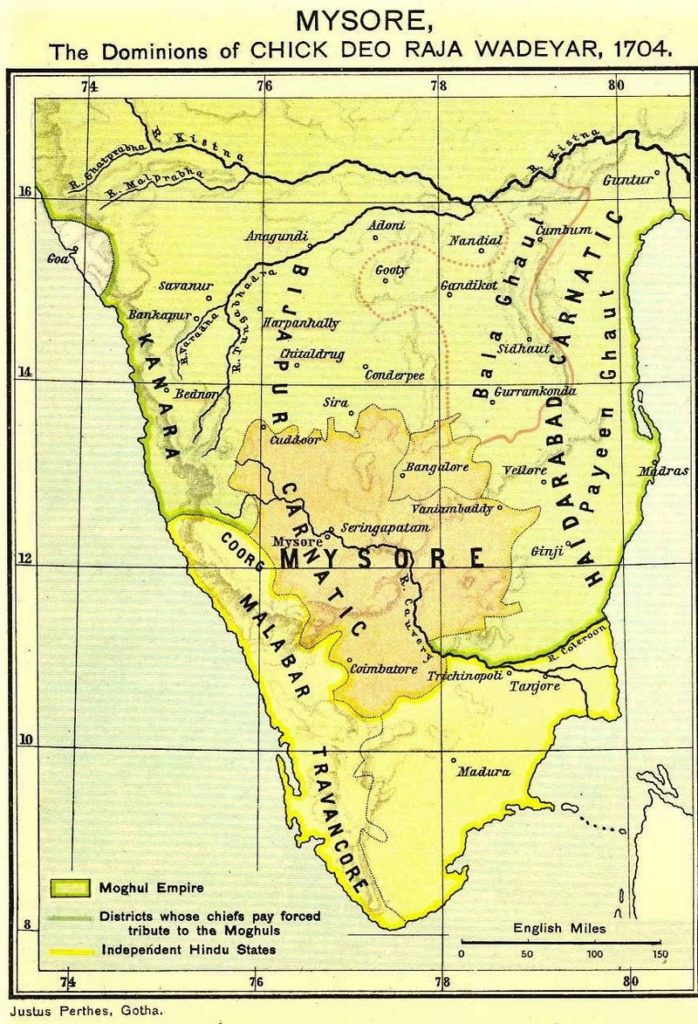

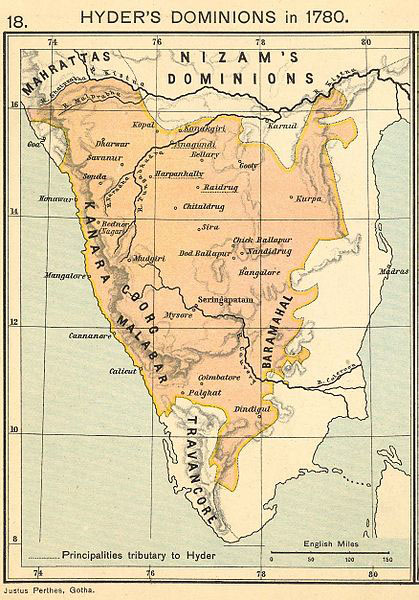

Mysore was an independent principality—landlocked, tiny, and on the brink of extinction. Haider Ali, a soldier of fortune who had made a mark fighting for Mysore, took command of the kingdom’s army. Haider Ali defended Mysore against the neighboring Maratha Kingdom, which lay to the north and was looking to extract tribute and expand its territory to Mysore’s detriment. Haider Ali and his son, Tipu Sultan, known as “the Tiger of Mysore,” expanded Mysore in all directions, bringing the Deccan peninsula under Mysore’s control. Bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west and the Western Ghat Mountains in the east and from the River Krishna in the north to beyond Dindigul in the southern Tamil Nadu district, greater Mysore had many major towns and ports. Its capital, deep inland, was the historic temple island of Seringapatam.

Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan modernized Mysore’s army, fielding in excess of 100,000 regulars organized into cushoons, risalas, and juqs, equivalent to brigades, battalions, and companies. Theirs was the best equipped and most disciplined of native armies. Most Indian soldiers still relied on swords and other edged weapons, with matchlock firearms restricted to elite troops, but Mysore was producing and distributing masses of flintlocks of superior quality. Most native forces depended on heavy cavalry—armored riders on armored horses and elephants. The Mysore army combined light cavalry and musket-wielding infantry trained by European mercenaries. Riders of “fighting camels” learned to fire their flintlocks on the run and with deadly accuracy.

The father and son were the first native rulers to grasp the British intent to subjugate them. Other indigenous rulers fared less well. In 1765, for example, after the Company defeated Mughal Emperor Shah Alam at Buxor, the British forced the emperor to grant the Company revenue collection rights in large northern provinces. But Company forces met their match in the 1766-69 First Mysore War. Besieged by Haider Ali inside the walled city of Madras, the company’s provincial capital in south India, the British sued for peace.

Further incursions by Company forces led to the Second Mysore War (1780-84). The father-son duo and their freedom fighters whipped Company forces in September 1780 at Pollilur, near the city of Kanchipuram, in part by deploying corps of rocketeers who fired explosive projectiles with terrifying efficiency at Company sepoys. Long familiar with the use of bamboo rockets for signaling, the Mysoreans built iron rockets and packed them with gunpowder. Tipu’s rocketeers were trained to launch projectiles from handheld or shoulder mounts or from carts massed for maximum effect. At Pollilurm, rockets caused great damage, fear, and anguish among Company forces. Sir Hector Munro called that defeat “the worst disaster that had befallen British arms in India”; dismay in the field reverberated at home in Britain.

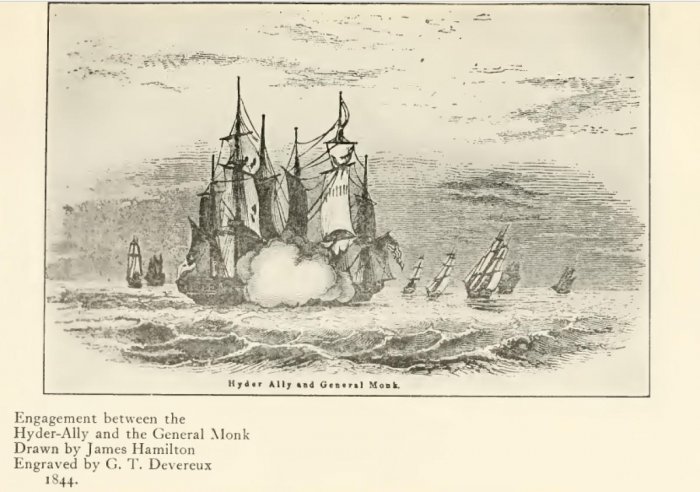

In revolutionary America, Mysorean resistance to British oppression inspired much admiration. In 1781, the Pennsylvania legislature commissioned a warship that it named the USS Hyder-Ally. Poet Philip Freneau, an ally of Thomas Jefferson, portrayed the vessel in verse:

From an Eastern prince she takes her name,

Who, smit with freedom’s sacred flame

Usurping Britons brought to shame,

His country’s wrongs avenging.

In 1782, three British warships attacked three American privateers, including Hyder-Ally, as the privateers escorted a fleet of five rebel merchantmen past Cape May and into Delaware Bay. The ensuing battle was a total rout for the British, who lost more than 50 sailors and every officer on the battleship General Monk, which the Americans captured. The hero of the day, Lieutenant Joshua Barney, captaining Hyder-Ally, was honored and sent with dispatches for Benjamin Franklin in France.

Haider and Tipu also were the subjects of mentions in dispatches by notable Americans. From Paris, Thomas Jefferson, minister to France, commented in detail about the delegation sent by Tipu to that nation. A young John Quincy Adams wrote about the British loss at Pollilur to his mother. A vogue developed for naming racehorses after Indian leaders. In Williams v. Cabarrus, a lawsuit brought in 1793 in North Carolina, the opposing parties disputed a wager made on a horse race. One of the horses was named “Hyder Ally.”

The Company had its revenge when General Lord Charles Cornwallis, who surrendered to George Washington at Yorktown in 1781, was named governor-general of India in 1786. Cornwallis led Company forces against Tipu Sultan during the Third Anglo-Mysore War (1790-92), forging alliances with other regional powers against Mysore.

Tipu Sultan, who refused to enter into alliances of convenience, survived to remain a thorn in the Empire’s side, leading to the Fourth Mysore War (1798-99). A coalition of the Marathas joined the Nizam, as Hyderabad’s ruler was known, the nawab of Carnatic, and other Company allies in laying siege to Tipu’s capital at Seringapatam. Tipu Sultan died defending Mysore and freedom. In response, John Russell, a Baptist minister in Providence, Rhode Island, gave a sermon on Independence Day 1800, describing to congregants Tipu’s death while fighting to remain autonomous. Tipu Sultan “defended his power with a spirit which showed he deserved it,” Russell said. “His death was worthy of a king.” The Company shipped captured Mysorean projectiles to Britain where armorer Sir William Congreve copied their features, producing what came to be called Congreve rockets.

Mysore slipped from Americans’ awareness, but a vestige of the Indian state entered American culture. In 1814, during a British naval siege of Baltimore, Maryland, American writer Francis Scott Key was aboard a truce ship. Watching a 25-hour barrage of Congreve rockets etching scarlet streaks across the dark sky and yet not bringing down Fort McHenry, Key wrote a doggerel verse that mentioned “the rockets’ red glare” and “bombs bursting in air” as the fort held out through the night. Set to the tune of “To Anacreon in Heaven,” a popular drinking tune, Key’s poem became the American national anthem, in the process immortalizing the Congreve rocket, descended from an ancestor with roots in the Kingdom of Mysore. In honor of that connection, at Wallops Island, Virginia, a National Aeronautics and Space Administration facility displays a painting of Mysorean rockets wreaking havoc among British troops during the Second Mysore War—a tribute to the arc of history linking nations halfway around the globe from one another.

Mohammed M. Masood, an independent historian in Bangalore, India, specializes in medieval Indian history. A candidate for a master’s degree in history, he is a numismatist, bibliophile, and collector of antique South Indian edged weapons. He blogs at www.bygonechronicles.com and can be reached at mujthahid@gmail.com