As America was feeling an urge for empire, Mark Twain and Theodore Roosevelt rumbled.

Reporters swarmed the end of a Manhattan pier as the liner SS Minnehaha docked on October 15, 1900. Mark Twain, among the most beloved of all Americans, had come home, a return newspapers treated as epochal.

Twain appeared at the top of the gangplank in his mature persona—bow tie, thick mustache, unkempt shock of curly white hair.

Correspondents shouted questions. Several pressed Twain about his criticism of the war America was waging against nationalists in the Philippine Islands. Before leaving London, the author had told a reporter for the New York World that the conflict was “a quagmire,” that the islands should be ruled “according to Filipino ideas,” and that the United States should “not try to get them under our heel” or intervene “in any other country that is not ours.”

“You’ve been quoted here as an anti-imperialist!” cried a reporter. “Well, I am,” Twain said. “A year ago I wasn’t. I thought it would be a great thing to give a whole lot of freedom to the Filipinos. But I guess now that it’s better to let them give it to themselves.” Subsequently, the author told an interviewer, “I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.”

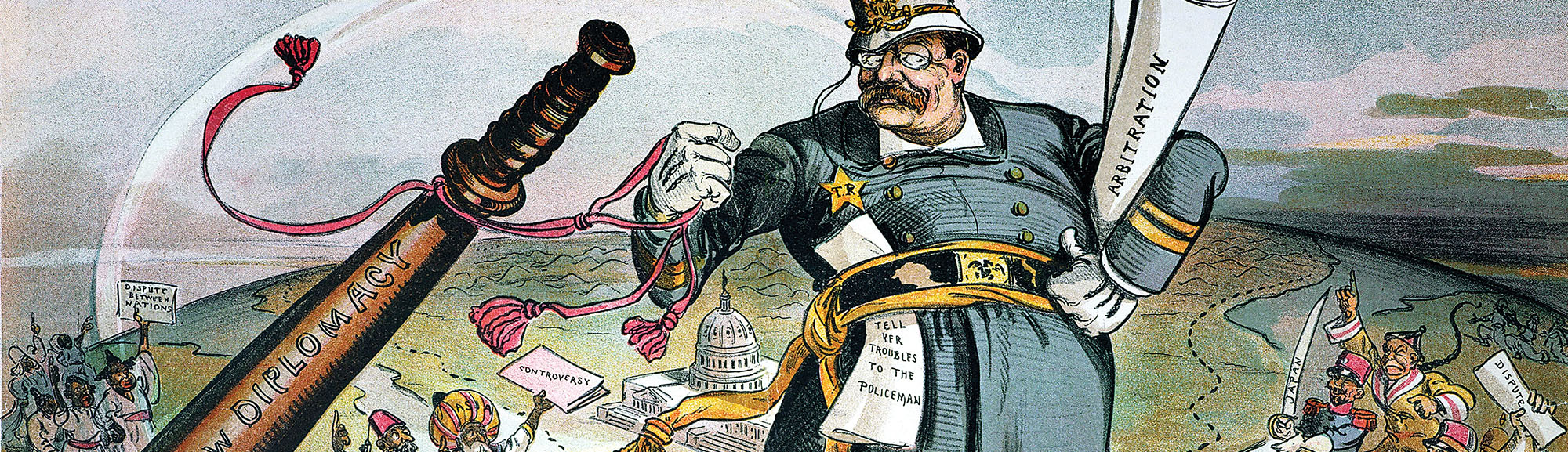

With those words, Twain plunged into that era’s great debate, arguably the farthest-reaching in American history. In the years around 1900, the United States leaped from continental empire to overseas empire by asserting power over Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Guam and, amid terrible violence, the Philippines. Theodore Roosevelt, the era’s iconic imperialist, considered this a leap toward national greatness. Twain thought that expansionism stood in contradiction to every American ideal.

As the debate over America-as-empire sharpened, Roosevelt came to embody the nation’s drive to project power overseas. Twain became Teddy’s most acerbic adversary. The men passionately framed the question that has been at the heart of American foreign policy debate ever since.

Roosevelt and Twain moved in overlapping circles and knew each other, but for years geography separated them. For much of the 1890s, Twain traveled and lived abroad. In Fiji, Australia, India, South Africa, and Mozambique, white rulers’ treatment of natives had appalled him. His frame of historical and cultural reference stretched far more broadly than Roosevelt’s. Twain saw nobility in many peoples, and abroad found much to admire—quite unlike Roosevelt, who believed that “the man who loves other countries as much as he does his own is quite as noxious a member of society as a man who loves other women as much as he loves his wife.” Instead of seeing the United States only from within, Twain compared his homeland to other powers. He saw his country rushing to reenact follies Twain believed had corrupted Britain, France, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Russia, and the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires. That way, the author warned, lay war, oligarchy, militarism, and suppression of freedom at home and abroad.

These adversaries were deliciously matched. Their views of life, freedom, duty, and the nature of human happiness could not have been further apart. World events divided them even before their direct confrontation. Germany’s 1897 seizure of Chinese port Kiaochow—later Tsingtao, now Qingdao—outraged both, but for different reasons. Twain opposed all foreign intervention in China; Roosevelt worried only that in the race for overseas concessions Germany was pulling ahead of the United States. Roosevelt considered colonialism a form of “Christian charity.” Twain pictured Christendom as “a majestic matron in flowing robes drenched with blood.”

Even though Twain’s most famous work, Huckleberry Finn, is full of coarse language and has as its hero a runaway rascal, Roosevelt acknowledged the novel to be a classic. He did not care for much else that Twain wrote, however, and especially disliked A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. Twain treated the Knights of the Round Table as objects of lusty satire—horrifying Roosevelt, who had revered the imaginary Arthurians since childhood.

Yet in intriguing ways, Roosevelt and Twain were remarkably similar. Both were fervent patriots who believed the United States had a sacred mission—though each defined that

mission quite differently. Both were writers and thinkers as well as activists. Most importantly, both were relentless self-promoters, born performers who carefully cultivated their public images. They loved to preach, reveled in the spotlight, and could not turn away from a crowd or a camera. Acutely aware of one another’s popularity, neither publicly denounced the other. Among friends, though, each was free with his feelings. Roosevelt said he would like to “skin Mark Twain alive.” Twain considered Roosevelt “clearly insane” and “the most formidable disaster that has befallen the country since the Civil War.”

Roosevelt did not conceive or organize or lead the imperialist movement. Neither did Twain fill any such roles for the anti-imperialists. Nonetheless the pair would become the most prominent, most admired, and most reviled spokesmen for their opposing causes.

“There comes a time in the life of a nation, as in the life of an individual, when it must face great responsibilities, whether it will or not!” Roosevelt said in one of his rousing speeches. “Our flag is a proud flag, and it stands for liberty and civilization. Where it has once floated, there must and shall be no return to tyranny or savagery!”

Twain detested this view. He believed the United States should withdraw from the Philippines and accept an independent Filipino nation—a notion Roosevelt deemed absurd. In a letter to fellow imperialist Rudyard Kipling, he scorned “the jack-fools who seriously think that any group of pirates and head-hunters needs nothing but independence in order that it be turned forthwith into a dark-hued New England town meeting.”

Soon after returning to New York in 1900, Twain addressed the City Club. He told a few stories and, slipping into his most disarming drawl, added that he knew enough about the Philippines “to have a strong aversion to sending our bright boys out there to fight with a disgraced musket under a polluted flag.” Several listeners took indignant exception.

Over the next two years, Twain wrote scathing critiques of the expansionist ethos. The pithiest was “Salutation Speech From the Nineteenth Century to the Twentieth, Taken Down In Shorthand by Mark Twain.” The Minneapolis Journal of December 29, 1900, included the broadside in a series of musings by famous men.

“I bring you the stately matron named Christendom, returning bedraggled, besmirched, and dishonored, from pirate raids in Kiaochow, Manchuria, South Africa, and the Philippines, with her soul full of meanness, her pocket full of boodle, and her mouth full of pious hypocrisies,” Twain wrote. “Give her soap and towel, but hide the looking glass.”

Anti-imperialists made Twain’s jibe into a card showing a female figure above a couplet—probably written by Twain himself:

Give her the glass; it may from error free her

When she shall see herself as others see her.

With these few lines, Twain secured his position as a movement’s eviscerating bard. The New York Anti-Imperialist League invited the author to become one of that body’s vice presidents.

“Yes, I shall be glad to be a vice president of the League,” he wrote back, “a useless because non-laboring one, but prodigiously endowed with sympathy for the cause.” Twain proudly held the title for the rest of his life.

Encouraged by the success of his salutation, Twain decided to codify his anti-imperialist creed in a full-length essay. The result was one of his most powerful pieces, “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” in which Twain slashes at the so-called civilized powers: Britain for its brutality in South Africa, others for dismembering China, and “the blessings-of-civilization trust” for dealing in “glass beads and theology, and Maxim guns and hymn books.” Twain especially rues America’s “bad mistake” in annexing the Philippines.

“It was a pity; it was a great pity, that error; that one grievous error, that irrevocable error,” Twain wrote. “For it was the very place and time to play the American game again. And at no cost. Rich winnings to be gathered in, too; rich and permanent; indestructible; a fortune transmissible forever to the children of the flag. Not land, not money, not dominion—no, something worth many times more than that dross: our share, the spectacle of a nation of long harassed and persecuted slaves set free through our influence; our posterity’s share, the golden memory of that fair deed.”

At the conclusion, Twain, in the wickedest paragraph in the literature of American anti-imperialism, imagines himself explaining the 1899 Philippines annexation to an ignoramus:

“There have been lies; yes, but they were told in a good cause. We have been treacherous; but that was only in order that real good might come out of apparent evil. True, we have crushed a deceived and confiding people; we have turned against the weak and the friendless who trusted us; we have stamped out a just and intelligent and well-ordered republic; we have stabbed an ally in the back and slapped the face of a guest; we have bought a Shadow from an enemy that hadn’t it to sell; we have robbed a trusting friend of his land and his liberty; we have invited our clean young men to shoulder a discredited musket and do bandit’s work under a flag which bandits have been accustomed to fear, not to follow; we have debauched America’s honor and blackened her face before the world; but each detail was for the best…And as for a flag for the Philippine Province, it is easily managed. We can have a special one—our States do it: we can have just our usual flag, with the white stripes painted black and the stars replaced by the skull and cross-bones.”

This venomous essay became one of Twain’s most popular articles. The American Anti-Imperialist League published “To the Person Sitting in Darkness” as a pamphlet, distributing 125,000 copies—paid for by tycoon Andrew Carnegie, who called the work “a new Gospel of Saint Mark…which I like better than anything I’ve read for many a day.” Reprints blossomed nationwide. Some newspapers ran editorials about “Darkness” day after day. “Mark Twain,” the Springfield Daily Republican reported, “has suddenly become the most influential anti-imperialist, and the most dreaded critic of the sacrosanct person in the White House, that the country contains.” The strong response encouraged Twain to press on. One essay offered an unorthodox apologia for George Washington:

“He did not write the Declaration of Independence, as some historians erroneously believe, but excused himself on the plea that he could not tell a lie. It was the intention of the Americans to erect a stately Democracy in their land, upon a basis of freedom and equality before the law for all; this Democracy was to be the friend of all oppressed weak peoples, never their oppressor; it was never to steal a weak land or its liberties; it was never to crush or betray struggling republics, but aid and encourage them with its sympathy. The Americans required that these noble principles be embodied in their Declaration of Independence and made the rock on which their government should forever rest. But George Washington strenuously objected. He said that such a Declaration would prove a lie…that as soon as the Democracy was strong enough it would wipe its feet on the Declaration and look around for something to steal—something weak, or something unwatched—and would find it; if it happened to be a republic, no matter; it would steal anything it could get.”

Twain emerged as an anti-imperialist much as Thoreau and Emerson, half a century before, had become abolitionists. Twain had a distinct contrarian impulse. His characters were often unconventional. Instinctive skepticism, however, does not explain the intensity of Twain’s opposition to American expansion. Life experience brought him to this point of view.

Partly as a result of foreign travel, Twain viewed race in more enlightened terms than did most Americans. Often he wrote admiringly about anti-colonial rebels. He saluted the nationalist Boxers in China, portrayed in the American press as missionary-slaughtering savages. “The Boxer is a patriot, he is the only patriot China has and I wish him success,” Twain wrote in a letter. To another correspondent, he said, “My sympathies are with the Chinese. They have been villainously dealt with by the sceptered thieves of Europe, and I hope they will drive all of the foreigners out and keep them out for good.”

Twain was always an iconoclast, but his pen never dripped as poisonously as when he was skewering American imperialism. In speeches, interviews, letters, and pamphlets, he scorned and condemned the expansionist project.

“We find a whole heap of fault with the war in South Africa, and feel moved to hysterics by the sufferings of the Boers, yet we don’t seem to feel very sorry for the natives in the Philippines,” he told a reporter. In a letter to a friend he confessed, “I am distressed because our President [William McKinley] has blundered up to his neck in the Philippine mess, and that I am grieved because this great big ignorant nation, which doesn’t even know the ABC facts of the Philippine episode, is in disgrace before the sarcastic world.” When the War Department, to encourage enlistments, began placing patriotic poems in newspapers, Twain sent one of the poets a note: “Will you allow me to say that I like these poems of yours very much? Especially the one which so vividly pictures the response of our young fellows when they were summoned to strike down an oppressor and set his victim free. Write a companion to it and show us how the young fellows respond when invited by the Government to go out into the Philippines on a land-stealing and liberty-crucifying campaign.” Twain even rewrote “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” to fit what he saw as the tenor of the times:

Mine eyes have seen the orgy of the launching

of the Sword

He is searching out the hoardings where the stranger’s

wealth is stored;

He hath loosed his fateful lightnings, and with woe

and death is stored,

His lust is marching on.

Twain’s writings and speeches of 1900-01 made him the anti-imperialist movement’s highest-profile star. Many anthologies of his work conspicuously exclude these works, possibly due to a censorious impulse that began with his wife. “Does it help the world to always rail at it?” Olivia Clemens asked her husband in a letter. “There is great & noble work being done, why not sometimes recognize that? Why always dwell on the evil until those who live beside you are crushed to the earth & you seem almost like a monomaniac?”

Twain agreed that some of his rants were too extreme for public consumption. Privately he looked forward to a day when he could be “as caustic, fiendish and devilish as possible” and publish tirades that would “make people’s hair curl.” Yet his side was steadily losing the political debate. The Senate ratified McKinley’s treaty making the Philippines an American territory. The Supreme Court ruled in the “insular cases” that American subjects in overseas territories are not entitled to constitutional rights. In the 1900 election, McKinley won a second term with Roosevelt as his new vice president.

The vice presidency, largely a meaningless job, pulled Roosevelt out of the public eye. After taking the oath of office on March 4, 1901, he presided over the Senate for four days, whereupon that body declared its customary nine-month recess. Most lawmakers left Washington. Roosevelt decamped to his Oyster Bay, New York, estate. Occasionally he made speeches, always returning to familiar themes. On September 5, the vice president told an audience in Burlington, Vermont, that American rule was “giving to the Philippines a degree of freedom which they could never have attained had we permitted them to fall into anarchy or under tyranny.”

The next day, Roosevelt decamped to Isle La Motte in Lake Champlain, near the Canadian border, where his friend Nelson Fisk, a former lieutenant governor of Vermont, had an estate. Roosevelt was entering Fisk’s home after a fete in the garden when the telephone rang. Answering it, Fisk beckoned Roosevelt inside. Murmurs rippled through the crowd in the yard until Senator Redfield Proctor (R-Vermont) emerged. “Friends, a cloud has fallen over this happy event,” he said. “It is my sad duty to inform you that President McKinley, while in the Temple of Music at Buffalo, was this afternoon shot by an anarchist.” McKinley died eight days later.

“I told William McKinley that it was a mistake to nominate this man in Philadelphia!” Senator Mark Hanna (R- Ohio) fumed aboard the funeral train. “I asked him if he realized what would happen if he should die. Now look! That damned cowboy is President of the United States!”

Twain saw the end at hand. “We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect & of respect for his high office,” he fumed. “We have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully.”

Despondent, Twain wrote a bitter lament. His observations, trenchant then, sound eerily appropriate today.

“It was impossible to save the Great Republic,” Twain wrote. “She was rotten to the heart. Lust of conquest had long ago done its work. Trampling upon the helpless abroad had taught her, by a natural process, to endure with apathy the like at home; multitudes who had applauded the crushing of other people’s liberties, lived to suffer for their mistake in their own persons. The government was irrevocably in the hands of the prodigiously rich and their hangers-on, the suffrage was become a mere machine, which they used as they chose. There was no principle but commercialism, no patriotism but of the pocket.”