It was perhaps the politest “battle” in human history.

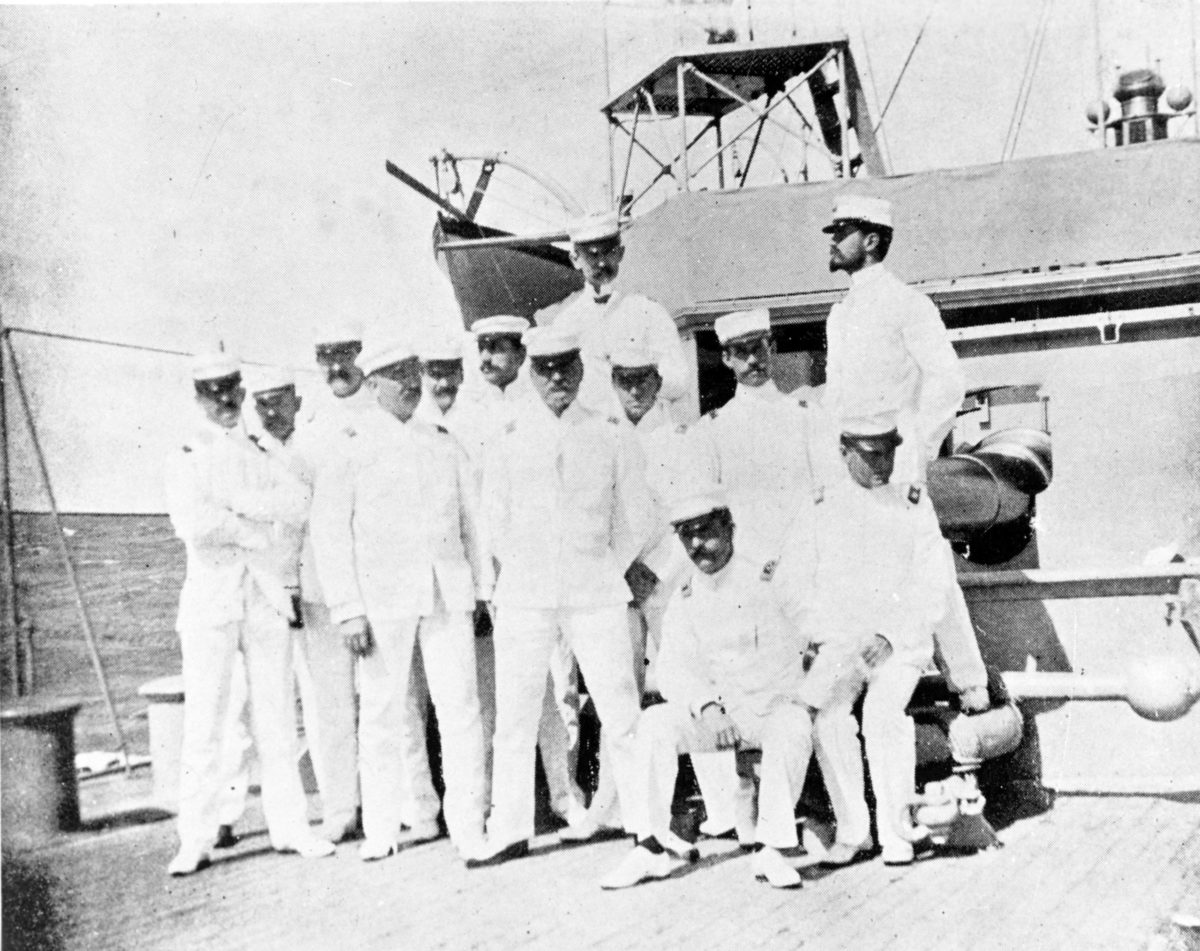

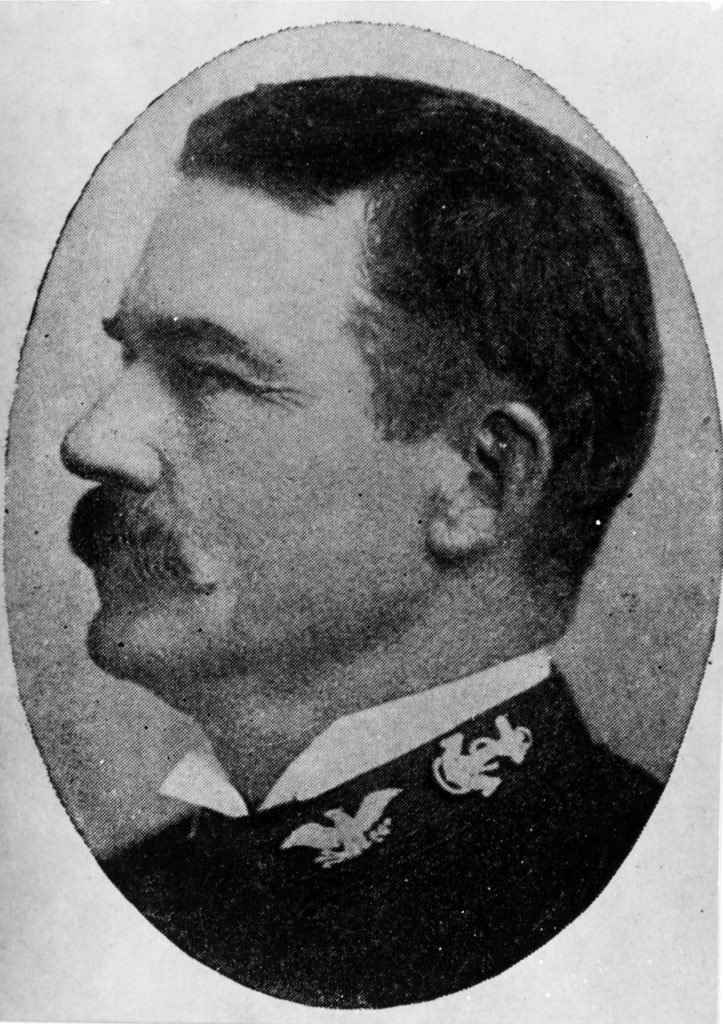

Upon entering Guam’s harbor on June 20, 1898, instead of experiencing the expected whizz of bullets and the booms of a cannonade, U.S. Navy Capt. Henry Glass and his crew aboard the re-commissioned cruiser USS Charleston were greeted on the beaches by curious residents who mistook Charleston’s warning shoots as a salute.

No one had bothered to tell the residents on the island that they were at war.

The small, neglected island under Spanish rule hadn’t received a message from Spain since April 14, 1898 — a full month before hostilities broke out between their protectorate and the United States.

That did not stop the Americans from attempting to seize the far-flung Spanish holding.

MISSION TO GUAM

Earlier that month, upon receiving orders from Secretary of the Navy John D. Long “to stop at the Spanish Island of Guam … [and] use such force as may be necessary to capture the port,” the Charleston, with Glass at the helm, steamed toward the Spanish-held island.

One sailor recalled, “When the news of our destination and object was learned aboard the Australia there was considerable excitement, of course, and the cause of many pow-wows as ‘What about Guam and where is it anyway, and what do we want of it?’”

A POLITE DISCUSSION ABOUT WAR

Once they arrived in Guam, the Americans were hankering for a fight and had Manifest Destiny on their minds. So the Americans began bombarding the fort at Santa Cruz.

Ironically, however, their act of violence was mistaken for a salute of respect, and the Spanish authorities on the island raced to obtain artillery to return the perceived salutations. As Guamanian officials approached the Charleston by way of rowboat, they were shocked to learn that a state of war existed between the United States and Spain and that they were now technically prisoners of war.

Glass then dispatched Lt. William Braunersreuther to meet with governor, Juan Marina Vega, and collect the surrender of the small Spanish garrison. According to Naval History and Heritage Command, Marina Vega was taken aback that he had to go on board the American vessel, as such an action was forbidden by Spanish law.

“I regret to have to decline this honor and to ask that you will kindly come on shore, where I await you to accede to your wishes as far as possible, and to agree to our mutual situations,” Gov. Vega responded.

Vega, however, eventually acquiesced, along with surrendering his small Spanish garrison to the Americans.

LEFT IN QUESTIONABLE HANDS

Glass, eager to sail on to Manila posthaste to join Commodore George Dewey’s fleet placed the island in the hands of Francisco Portusach, a 30-year-old naturalized U.S. citizen.

The former janitor was in the right place at the right time. Portusach’s only qualifying attribute was that he was an American, but that was enough for Glass, and he placed the island — and U.S. interests — in Portusach’s less than capable hands.

Unsurprisingly, after Glass’ departure, Portusach was unable to solidify his position as governor and was overthrown by Spaniard Jose Sisto, a former public administrator. Sisto, too, had a short reign and was quickly overthrown by the native Chamorro population.

The 1898 Treaty of Paris formalized the handover of Guam as a U.S. territory, which it remains today.