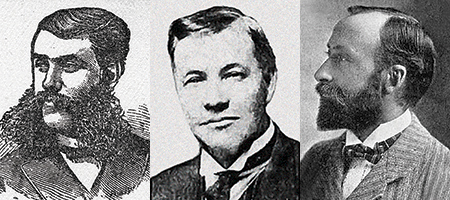

David, John and Charles Swartz—three country boys raised in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley in the wake of the Civil War—came to the Texas frontier to seek their fortunes. As professional photographers they found fame if not fortune. Over the course of four decades they changed both the art and business of photography in significant ways while chronicling life in the Lone Star State. Their personal lives were something else, the stuff of dime novels, marred by tragedy, marital problems, bankruptcy and mental illness.

David, John and Charles were among the 11 children born to Philip and Susan Swartz between 1844 and 1864. David, the seventh child, was born in 1854; John, the ninth, followed in 1858; and Charles, the youngest sibling, was born in 1864. Parents and children alike worked in the family mills (flour and lumber), a necessity even before the war, as Philip Swartz did not own slaves. At some point each of the brothers decided that mill work was not the life for him and hit the road. David went first, heading north to Dayton, Ohio, where he tried his hand at portrait photography and took up with Nellie Barnum, a distant relative of traveling showman P.T. Barnum with her own strong Bohemian streak. She, too, was a photographer, which in part explains David’s attraction to her. The lovers soon struck out for Texas, where they worked as itinerant photographers, traveling from small town to small town and offering their services to the locals. That worked until they arrived in staid Cleburne in 1879 and locals discovered they were living together unmarried. When the rumors made it into the local paper, the pair hurriedly left town. On Sept. 1, 1880, the chastened couple tied the knot in Austin. Four years later they landed in Fort Worth, a town emerging from its frontier roots with a population of little more than 8,000—big enough to provide steady employment for three working photographers even before the Swartzes arrived. David Swartz’s first studio was in Hell’s Half Acre, Fort Worth’s red-light district. He relocated uptown as soon as he was able.

Swartz advertised heavily in the newspapers and undercut competitors’ prices. He also did more than just take pictures; a traditional artist, he rendered portraits in several mediums and made reproductions. Among the latter he produced popular life-sized portraits of Texas legends Sam Houston and David Crockett from original paintings. In letters to his family back home in Virginia he talked up his success.

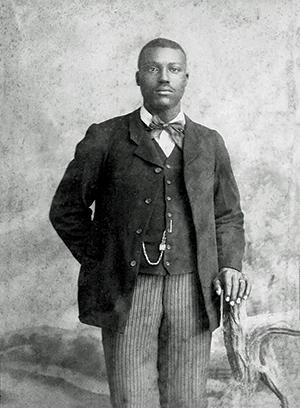

David’s rosy picture of life in Texas persuaded John to head west in 1885. He apprenticed under his big brother (doing business as D.H. Swartz & Bro.) before striking out on his own and opening a studio some 65 miles to the north in Gainesville. Over time John proved an even better photographer than David, though big brother considered himself an artiste and entrepreneur first and a photographer second. John thrived in Gainesville and while there fell in love with one Lydia B. “Blanche” Buck, whom he married in 1895. The couple soon returned to Fort Worth, John renting studio space at 705½ Main (the “½” meaning upstairs). It would remain his business address over the next 18 years and make history in late 1900. John had learned well from his big brother, for he, too, advertised heavily in Fort Worth and surrounding communities. Of note were his social views, quite broad-minded for the place and time. He actively solicited the “colored trade,” advertising to black residents in the Colored City Directory. He may not have been a trailblazer, but he was certainly enlightened in his racial attitudes.

Little brother Charles was the last to land in Fort Worth, coming for a working visit in 1890 to see whether his brothers’ glowing reports were true. Impressed, he returned home to the Shenandoah Valley only long enough to marry his sweetheart, Virginia “Jennie” Heagy, and await the birth of the couple’s first child, Charles Jr. The growing young family then moved to Fort Worth. In time it became clear Jennie was not as smitten with life in Texas as her husband. She pined for home. Like John before him, Charles apprenticed with his brothers before opening his own studio in 1899, just one block from David’s.

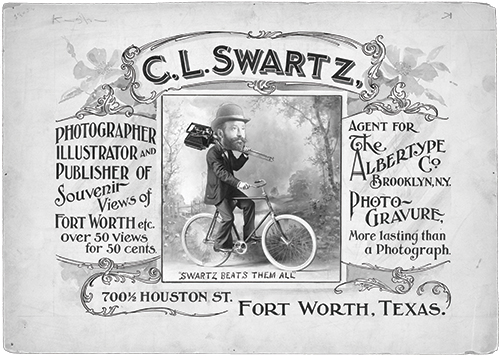

For a brief time in the late 1890s all three brothers were working in the same town as friendly rivals. Charles distinguished his work by advertising himself as a “view artist,” meaning he specialized in outdoor photography—street scenes, architecture, bird’s-eye views, etc. He became a familiar sight around town, peddling his bicycle along the dusty streets, heavy box camera balanced precariously over one shoulder. Like his brothers before him, he also advertised relentlessly, in the city directory and newspapers and by printing up and passing out business cards. Charles’ personal life may not have been as rosy as that of his brothers. In February 1904 Jennie gave birth to their second child, Louise May, but a year and a half later she returned to Virginia with the children. They never saw Charles again.

On the business side the Swartz brothers experienced ups and downs. They practiced photography in the heyday of cabinet cards—studio photographs mounted on fancy card stock with logos on the front and advertising on the back. The cabinet card had replaced the older carte de visite, which functioned more as a calling card than a picture for display. Cabinet cards became fancier and fancier, bigger and bigger, providing steady employment for professional photographers catering to the middle and upper classes.

Decades would pass before historians came to recognize the Swartz brothers’ photographic legacy, as their work lay scattered among countless collectors and repositories

The business changed dramatically around the turn of the 19th century after Kodak rolled out handy personal box cameras preloaded with film. No longer limited to paid studio sittings, everyone could be his own photographer. The Swartz brothers adapted, adding film developing to the services they offered. David and Charles also mass marketed their work in the form of cheaply bound souvenir viewbooks. In 1890 David self-published Photographs of Fort Worth, a sampling of the photographs and drawings he sold from his studio. He put out a second printing in 1899, while New York–based Albertype Co. published a third edition in 1917 without his involvement. All three used David’s 1880s images.

Fortune continued to smile on Charles. It didn’t hurt that he was a favorite of Mrs. Henrie Gorman, society grande dame and founding editor of The Bohemian, Fort Worth’s literary magazine, in which his work appeared. In 1901 Charles published nearly 100 of his photographs in Views of Fort Worth, Texas. He earned a royalty on each 50-cent book, though he surrendered all rights to Albertype. Charles also followed his big brother’s earlier example by turning some of his best images into picture postcards, a correspondence medium just catching on.

In the late 1890s David suffered a series of financial setbacks that drove him out of business in 1900. He moved his wife and three sons back East to Ohio to be near Nellie’s family, but his marriage fell apart anyway. He returned to Texas alone, settling in Dallas and reinventing himself as “Doctor” David Swartz, a purveyor of “medicines and toilet preparations” for women. As always he proved an entrepreneur par excellence and made ambitious plans to expand.

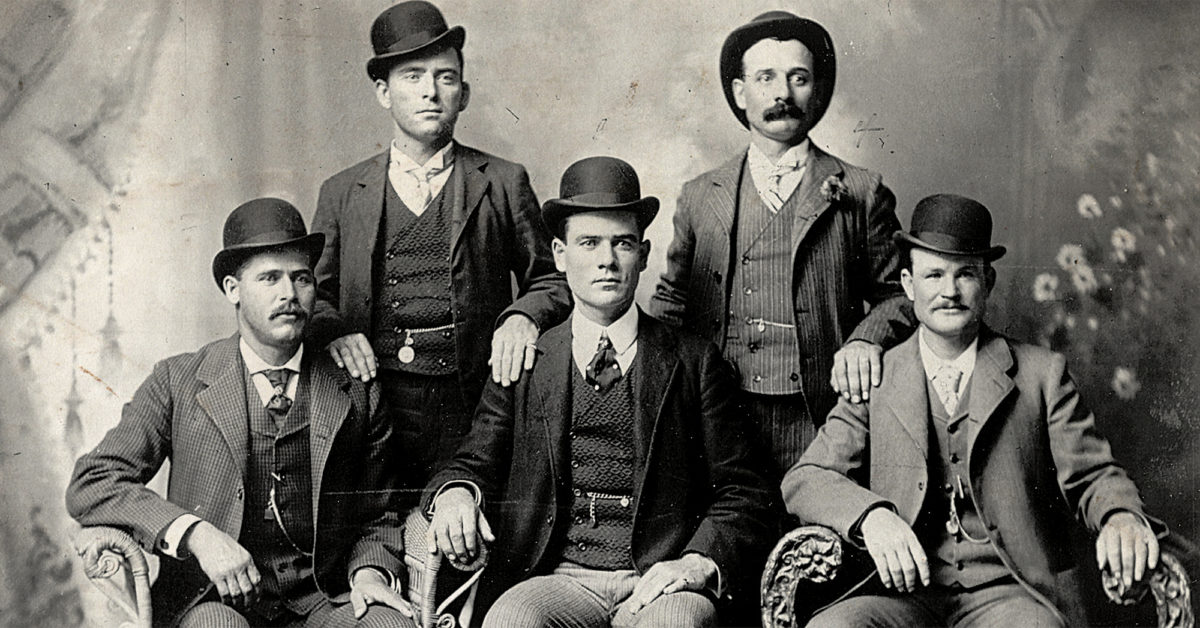

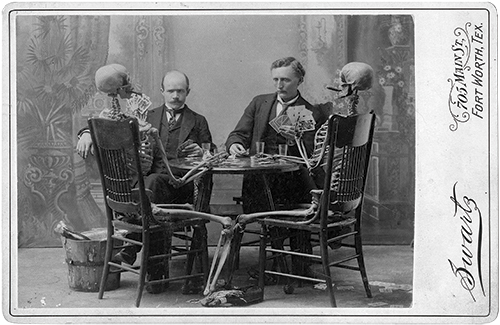

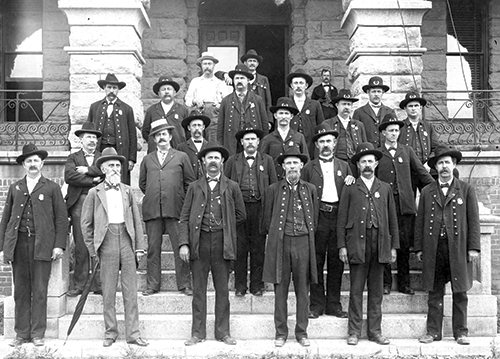

John and Charles remained in Fort Worth and in the photography business but followed different paths. Charles fell on rocky financial times that forced him to downsize and take on more contract work. John remained a studio photographer, and his best work won numerous professional awards. An unexpected highlight of his career came on Nov. 21, 1900, when five well-dressed strangers strolled into his Main Street studio seeking a group portrait. John had no idea they were members of the notorious outlaw gang known as the Wild Bunch, come to Fort Worth to lie low after having robbed a bank in Winnemucca, Nev. John posed the five against a studio backdrop and took multiple photographs for each to keep. But he retained at least one image for promotional display. That photo caught the eye of passing Fort Worth police detective Charlie Scott, who recognized two members of the gang and got word to the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. By then the quintet had skipped town. The portrait they left behind went on to become an iconic image in Western outlaw history, garnering its creator name recognition.

Charles’ life ended tragically in the fall of 1905, soon after Jennie had returned to Virginia with their two kids. That October 6 he was on the south side of Fort Worth, having accepted a commission to photograph an industrial plant. Arriving on scene, he had set up his camera atop a railroad embankment and busied himself clearing the foreground when he heard an approaching train, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (“Katy”) Flyer. Rushing to save his camera, Charles was struck by the Flyer and died on the spot of massive internal injuries. Jennie and children did not attend the funeral. He was buried in Fort Worth’s Oakwood Cemetery. A city court appointed John executor of Charles’ estate and guardian of his brother’s children. He later became Jennie’s guardian, after her family committed her to an asylum in Staunton, Va. She died there in 1913. Until the children attained their majority, John continued to look after their interests.

Charles had set up his camera atop a railroad embankment and busied himself clearing the foreground when he heard an approaching train, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (“Katy”) Flyer. Rushing to save his camera, he was struck by the Flyer and died on the spot of massive internal injuries

Meanwhile, John’s own life was not going so well. First his business hit the skids. Then, in 1912, wife Blanche took the kids and moved in with her parents in Los Angeles. That same year John sold out to George Bryant and went to work for the new studio owner. Blanche and John subsequently divorced, and he lost touch with his children. A few years later he relaunched his photography business, hanging on until 1918, when he moved back to Virginia. He was the last working photographer among the brothers. The 1930 census, the last in which he appears, describes him as a farm laborer living in the household of older brother Lemuel and wife, a couple that had lost their own son to suicide by shotgun in 1916. John died on Jan. 17, 1937, and is buried in Mount Jackson, Va.

David sought in vain to reconnect with Nellie before moving to southern California for his health. He spent his waning years in poverty, dying at Los Angeles County Hospital on Nov. 26, 1918. Nellie had his body shipped to Dayton, Ohio, for burial

With their remains scattered nationwide and their work scattered to the four winds, the Swartz brothers faded into history. So obscure did they become that some historians (like this one) mistakenly conflated the three into one mythical person, “John David Charles Swartz.” Only in the last few years has the trio emerged from the shadows, starting with a retrospective exhibition of their work at the Fort Worth Public Library in 2013.

The Swartz brothers deserve to be remembered for more than just their soap opera lives, for they had a lasting influence on their chosen field and on Fort Worth history. Over the course of nearly four decades they took thousands of images of people, places and events, only a few hundred of which have been identified. Without those pictures Fort Worth’s visual history would be immensely poorer. Their pictures chronicle the city and its people, offering a window into how residents lived around the turn of the century.

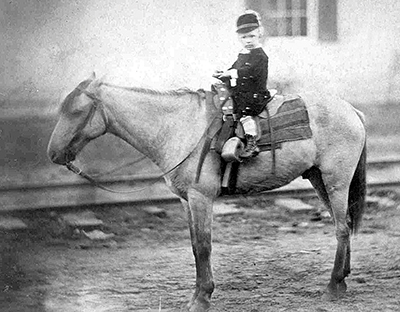

Among the Swartzes’ known images are portraits of single young men and women dressed to the nines and staring resolutely into the camera. It seems likely at least some of those portraits were swapped as part of the mail-order bride business that flourished in the frontier West, as no potential bride or groom was likely to commit to marriage without getting a look at her or his future mate. Scores of baby pictures snapped by the Swartzes have survived. The infants, often posed in christening gowns, remain largely unidentified, but the importance of that niche to the professional photographer’s bottom line is readily apparent. The same has long been true of pictures of children. What proud parent isn’t happy to fork over money to a studio photographer for a timeless image of their little darling(s)? The brothers left a trove of photos of Fort Worth families, most formally posed in a traditional grouping centered on the patriarch.

The Swartzes also left dozens of portraits of black and Hispanic residents. Such images are rare for three reasons. For one, minorities comprised no more than 8 percent of Fort Worth’s population in the late 19th century. For another, white photographers (i.e., virtually all studio photographers of the era) did not as a rule seek out such customers. Finally, working-class folks, which included virtually all minorities, did not have the disposable income to spend on such luxury items as studio portraits.

On the business side the Swartzes proved creative, adaptable entrepreneurs (see sidebar, opposite). They used the media of their day to advertise aggressively and offered countless specials and promotions to get foot traffic into their studios. Relentless marketers, they displayed their work in the windows of banks and saloons where the greatest number of passersby would see it. They multiplied the value of their work by printing the images in viewbooks and on postcards. Neither David nor Charles achieved lasting financial security, but they remained on the cutting edge of the business, and as they expanded operations, the brothers trained the next generation of photographers by hiring assistants (aka “technicians”).

On the technical side they brought the latest innovations in photography to the heartland. On election day 1888 David used the new “magic lantern” technology to put on a public slide show, The Fort Worth Gazette having hired him to chronicle the presidential campaign in photos to a rapt audience. He also anticipated modern-day office supply stores by offering copying services if one brought in an existing photograph or painting. Doing business as the Lone Star Copying House, he advertised “duplicates cheap,” subsequently rendering portraits of Crockett, Houston and President Benjamin Harrison, though none of the three had visited Fort Worth.

By the time the last Swartz brother left Fort Worth in 1918, dozens of professional photographers and film developers had filled the void. Few even noticed John’s departure. The Swartzes were no longer news. Decades would pass before historians came to recognize their photographic legacy, as their work lay scattered among countless collectors and repositories. Would Mathew Brady be a household name had his iconic Civil War images remained scattered from hell to Georgia in private hands instead of finding a place of honor in the Library of Congress? The Swartz brothers’ gallery of work should be held in similar regard. WW

Fort Worth author Richard Selcer is a frequent contributor to Wild West and often writes articles and books set in his hometown or Dallas. This article is adapted from his 2019 book Photographing Texas: The Swartz Brothers, 1880–1918, which is recommended for further reading. This article was published in the August 2020 issue of Wild West.