Influenza is usually a mild seasonal disease, but in 1918-19 a strain of influenza that may have originated in the United States killed tens of millions. In Influenza: The Hundred Year Hunt to Cure the Deadliest Disease in History (Touchstone, 2018), Jeremy Brown, MD, an emergency physician and director of the Office of Emergency Care Research at the National Institutes of Health, explains that pandemic and discusses what might prevent a reprise.

Why was 1918-19 so bad? The virus was so different from previous influenza viruses, victims’ immune systems couldn’t recognize it and

fight it. Additionally, we believe that some patients’ immune systems overreacted to the virus and attacked the body’s own healthy lung cells. This caused severe lung damage and made victims vulnerable to a secondary bacterial pneumonia which was likely the real killer. In 1918, there were no antibiotics to treat these bacterial infections. The virus multiplied rapidly in the crowded living conditions of the time, and unprecedented numbers of young soldiers were living in cramped barracks and traveling in ships’ holds on their way to Europe. Within months, the pandemic had gone all over the world.

Where did the pandemic originate? The 1918 virus originated in birds, then jumped into an intermediary host, probably pigs, and then to humans. Haskell County in western Kansas may have been ground zero around January 1918. Army recruits from there mustered at Camp Funston near Manhattan, Kansas, 300 miles east. Sickness broke out at Funston in March 1918. Then the disease spread from camp to camp before breaking out into the civilian population in the United States and Europe. Pandemic influenza had two waves. the first was less severe and ended around June 1918. But the virus returned in October and hit every continent except Antarctica. Some experts, trying to explain the rapidity of the disease’s spread, believe a less virulent bird flu virus had jumped to humans in France in 1916 and had two years to spread before mutating into its deadly form. Still others believe the second wave started in June 1918 in South China, where the new virus may have mutated in domestic fowl and infected people, including the 140,000 Chinese workers brought to France during the Great War to dig trenches and clear battlefields.

The pandemic burned itself out. Why? The most likely explanation is that eventually everyone who could be infected had either died or recovered. People who were unaffected or had mild cases either had strong immune systems or had been exposed previously, possibly to a similar flu strain that caused a large outbreak in 1898. The 1918 virus may have killed many young soldiers because they were born after that 1898 epidemic and so did not develop immunity.

Explain the hunt for the “dead” 1918 virus. In 1951, a virologist’s chance remark about the possibility that the 1918 virus might have survived in bodies buried in permafrost intrigued Johan Hultin, a graduate student at the University of Iowa. Hultin traveled to Brevig Mission, a remote Inuit village in Alaska, seeking bodies of flu victims that had remained frozen since burial. Although he found the lung samples he was looking for, Hultin was never able to grow the flu virus from them. Then in the early 1990s, Jeffrey Taubenberger, a pathologist at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, realized that the 1918 virus might be found in tissue samples preserved from the autopsies of soldiers who had died in the pandemic. Taubenberger finally identified a sample of the virus on a slide of lung tissue from Army Private Roscoe Vaughan, and he published his breakthrough in 1997. Johan Hultin, then 72, decided to return to Alaska some 50 years after his failed expedition there. At Brevig Mission, Hultin found frozen specimens. He mailed them to Taubenberger, who finally had enough samples to reconstruct the entire genome of the 1918 virus.

Why was it important to resurrect the 1918 virus? Although we discovered the genetic makeup and shape of the 1918 virus, that does not tell us why the virus was so lethal. To know that, you need to watch it infect animals; ferrets and guinea pigs are used. Only through these experiments with the resurrected virus can scientists see it in action, understand how it works, and hopefully find a cure.

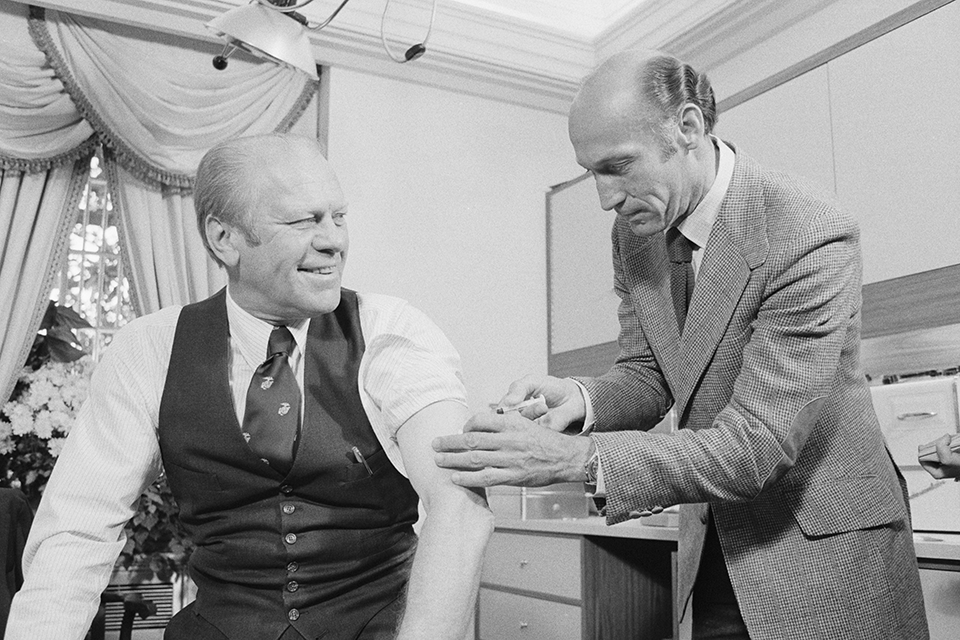

Explain the 1976 swine flu outbreak. That year, soldiers at Fort Dix in New Jersey came down with an unknown flu strain. One man died. The Centers for Disease Control identified the 1976 flu strain as a descendant of the 1918 virus and believed that the virus had jumped

to humans from pigs. None of the sick soldiers had had contact with swine. Public health officials worried that this flu could spread like the 1918 virus. A vaccine was quickly formulated, and the CDC recommended that all Americans be inoculated. President Gerald Ford accepted the recommendation but drug companies, worried about side effects, pressed the government to indemnify them against lawsuits. Sure enough, reports came in that right after vaccination some people had become ill or had a heart attack or stroke. However, statistically, every day a number of people are going to have a heart attack whether they’ve had a flu vaccination or not. People connected dots that were not there. The vaccine program was widely criticized and the CDC’s head was forced out.

Annual flu shot—yes or no? Public health officials recommend that every year all Americans over age six months get a flu vaccine. Influenza, however, is a shapeshifter. It mutates quickly into strains the body doesn’t recognize. In a good year, if scientists have projected correctly about which strains will be circulating that season, the vaccine is only 50 percent effective. The 2017-18 vaccine was 20 percent to 40 percent effective. In the United Kingdom and much of Europe, the vaccine is only recommended for the very young, the elderly, pregnant women, and those with weakened immune systems or chronic disease.

Can scientists prevent another 1918? Pessimists say it is only a matter of time before another pandemic occurs. We need to work hard at prevention and be ready to treat a lot of sick people. Optimists say the chances of another 1918 are very small. There have been other pandemics but none remotely close to 1918 in magnitude. Today we have antibiotics to cure secondary bacterial pneumonias and we have vaccines that are at least somewhat effective. But both sides agree that to prevent another influenza catastrophe, we need to study the 1918 virus, learn how it caused its damage and how it spread so quickly.