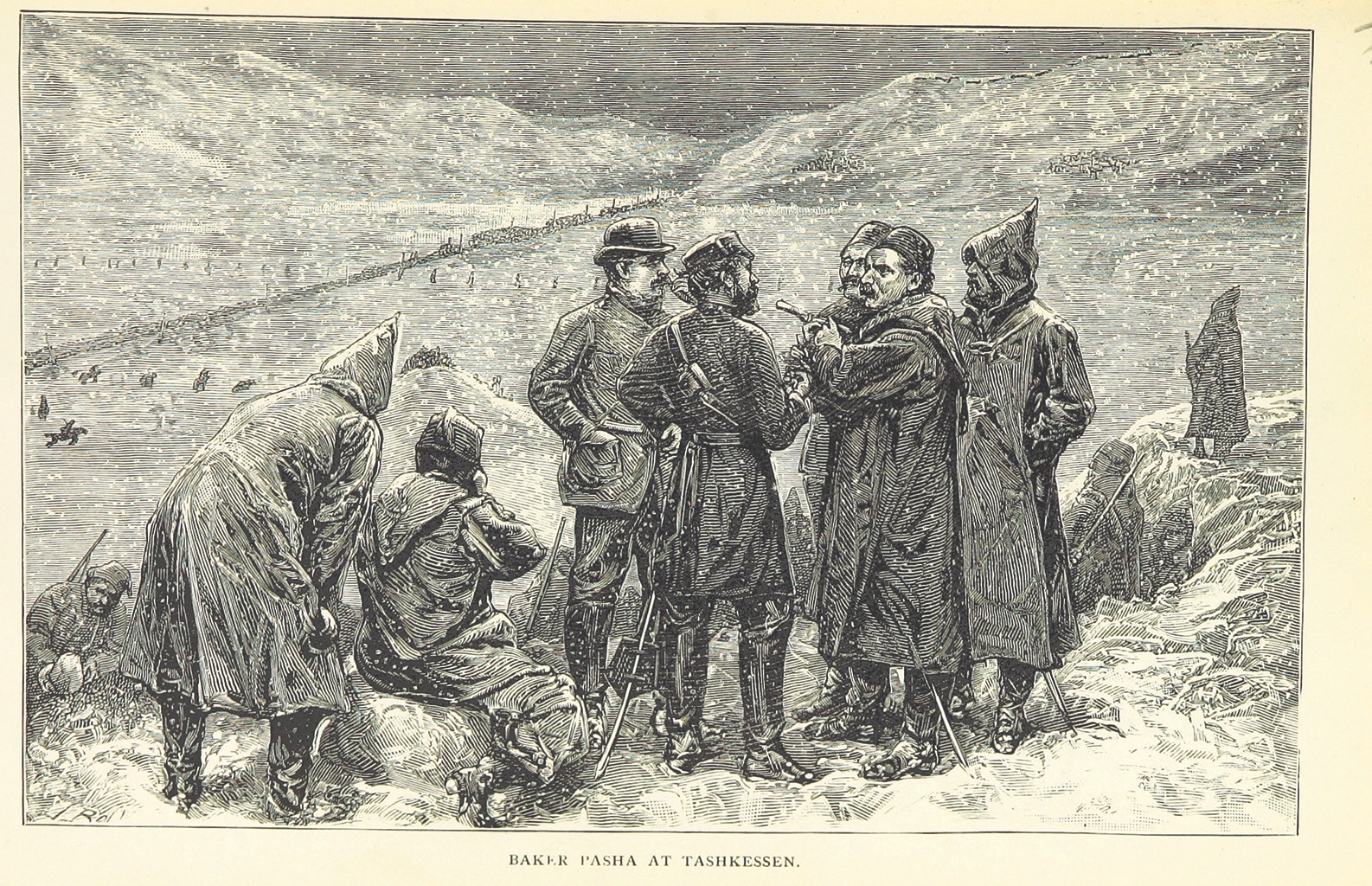

On Dec. 31, 1877, amid the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, some 25,000 Russian soldiers under General Joseph Gourko advanced on the Bulgarian village of Tashkessen. Waiting for them from the vantage of three knolls were a few thousand bedraggled Ottoman soldiers under Valentine Baker, a disgraced expat British officer. Sent to delay the advancing Russians, Baker’s Turks faced desperate odds.

The Russians had made slow progress in Bulgaria since declaring war on the Ottoman empire that spring. But their capture of Plevna in early December after a five-month siege freed up tens of thousands of troops, with whom the Russians renewed their southern offensive toward Constantinople, the Ottoman capital. By month’s end Gourko’s army had outflanked Turkish defenders in the Balkan Mountains, leaving in its wake Shakir Pasha’s entrenched army of 16,000 hungry, poorly supplied soldiers. Guided out of the mountains by local Bulgarians, Gourko’s columns raced toward Sofia to cut off Shakir’s line of retreat. The pasha’s only hope of escape was Baker’s delaying force at Tashkessen.

The Englishman conspicuously marched his Ottoman troops back and forth to dupe the enemy into thinking he had a much larger force. Reluctant to assault Baker’s line until reinforcements arrived, the Russians held off for four critical days, providing Shakir precious time to evacuate his army. Meanwhile, the pasha sent reinforcements to Baker, boosting the latter’s strength to nearly 3,000 men.

When pressed, Baker planned to fall back to the head of Tashkessen Pass. There he would wedge his battalions into the gap, much as Spartan King Leonidas’ 300 had done at Thermopylae in 480 bc. He hoped the stronger position and broken ground leading to it would sufficiently delay the Russian advance.

On December 31 Gourko’s 25,000 Russians tried to force their way past Baker’s left flank, just as Persian King Xerxes had at Thermopylae. Baker extended that flank and managed to hold position. When Russian numbers proved overwhelming, Baker ordered his battalions back as planned, with his cavalry covering the withdrawal. The advancing Russians fell into disarray while climbing the broken terrain toward the pass. On reaching Baker’s second line they renewed their attacks, but they were disjointed and lacked sufficient artillery support, nullifying their advantage.

The Turks withstood repeated assaults. Finally, after 10 hours of fighting, Baker and his surviving troops slipped away in darkness to rejoin Shakir’s army, which had fled south. Though Baker had suffered some 800 casualties, he had spoiled Gourko’s chance to destroy Shakir’s army.

The war ended in March 1878 with a Russian victory, and the action at Tashkessen was all but forgotten. In an 1892 lecture on Tashkessen to the Military Society of Ireland, British Col. Sir John Frederick Maurice said “In my judgment a knowledge of the facts of this little incident is in itself much more valuable to an officer than any theories we can lay down about it.”

Take the initiative, even on the defensive. Baker didn’t allow the Russians to dictate his strategy; he forced them to alter theirs.

Know the ground. Baker had passed through Tashkessen before the battle, and his decision to withdraw to its hilly terrain offset the Russian superiority in numbers.

Every moment gained is time lost to the enemy. Baker did everything he could to buy time for Shakir’s retreat, ensuring the larger force’s survival.

Resourceful leadership goes a long way. Baker’s energy and determination enabled him to successfully carry out his delaying action