On Oct. 20, 1740, Emperor Charles VI of the Austrian Hapsburg monarchy died, and his eldest daughter, Maria Theresa, assumed the throne, with husband Francis Stephen as nominal co-ruler. Two months later Frederick II of Prussia—pouncing on the contentious issue of female succession—demanded Maria Theresa cede him all or part of the Bohemian duchies of Silesia in exchange for his support of her sovereignty. In so doing, the Prussian king had grossly underestimated the 23-year-old empress, who, though inexperienced, proved a quick learner and of no mind to cede one of her realm’s most mineral-rich regions to a bully she dismissed as “that evil man.” Frederick invaded Silesia, Maria Theresa dispatched a 20,000-man army under Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg to eject him, and the War of the Austrian Succession was on.

Prussian troops swiftly occupied most of Silesia, and Frederick sent them into winter quarters expecting Maria Theresa to accept his fait accompli. Neipperg, however, marched around the main Prussian force to relieve the besieged city of Neisse. Frederick moved north to intercept him, only to find the Austrians encamped at Mollwitz, in position to cut off his lines of supply and communication. On the morning of April 10, 1741, the Prussian king, having learned of the enemy’s position from captured Austrian soldiers, advanced through snow and fog to within a mile of Neipperg’s camp. Instead of ordering an immediate charge, however, Frederick—in battle for the first time—took some 90 minutes to form his estimated 22,000 troops into two lines, compounding that error by miscalculating the distance to the Oder River on his right and deploying some units behind a bend in the river that kept them out of the fight. Initially surprised to find the Prussians at his rear, Neipperg had plenty of time to turn his battle lines 180 degrees, and by 1 p.m. both sides were ready to engage.

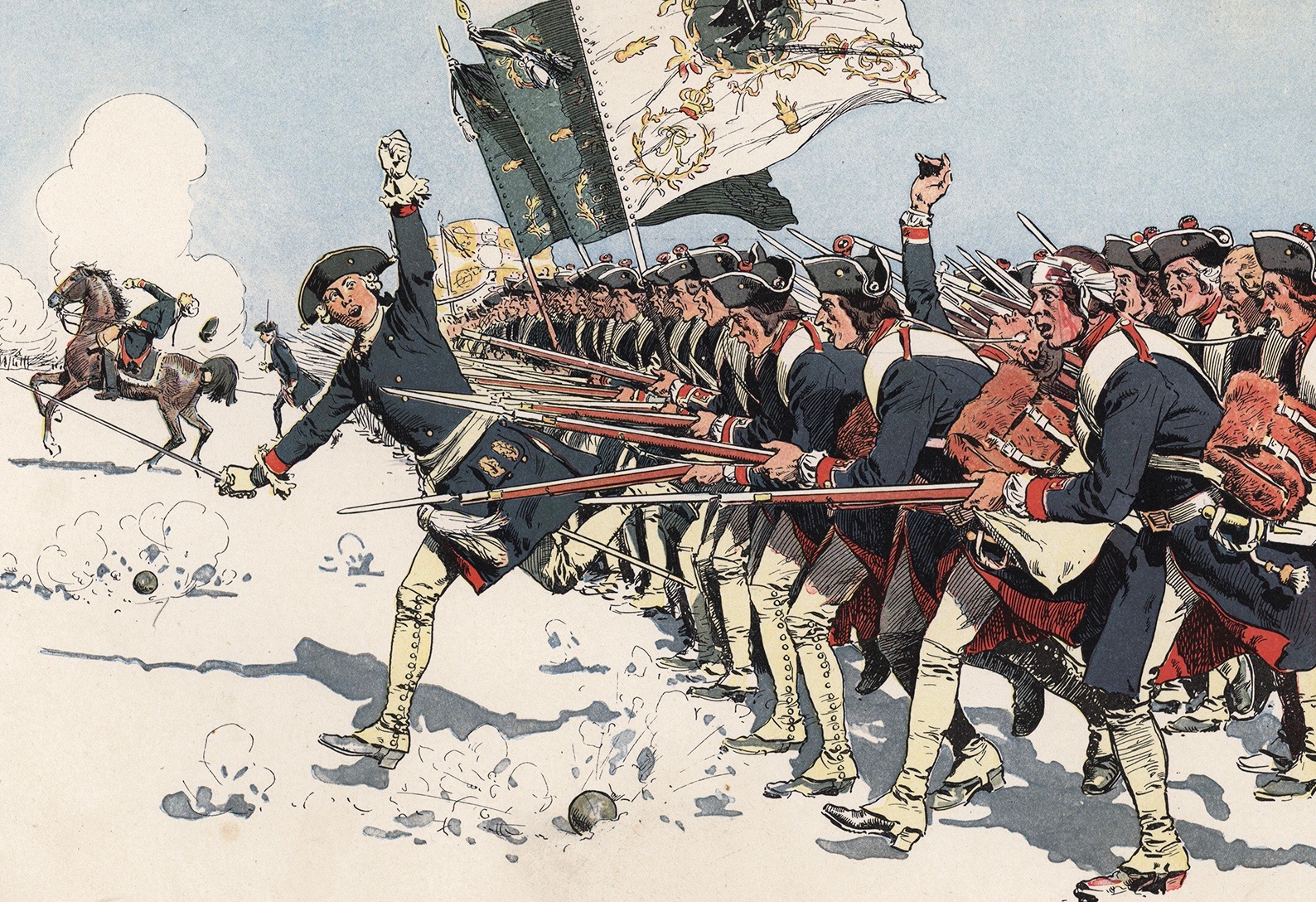

Neipperg struck first with a charge by six cavalry regiments—upward of 4,500 troopers under Lt. Gen. Carl von Römer—into the strangely stationary cavalry on the Prussian right, scattering it and then crashing into the Prussian infantry. Anticipating the worst, Frederick’s veteran general, Kurt Christophe Graf von Schwerin, advised the king to quit the field. As he did so, Frederick was nearly caught and shot.

Meanwhile, the Prussians had rallied to stop the Austrian horse and drop Römer with a shot to the head. Schwerin’s infantry commanders on both wings were also dead, but when an officer asked where they should retreat, the brash Prussian general reportedly replied, “We’ll retreat over the bodies of our enemies.” He soon restored order, and after his troops beat back a second Austrian cavalry attack on his left flank, he ordered a general advance. The well-drilled Prussian foot soon drove the Austrians from the field, handing the absent Prussian king—later to be known as Frederick the Great—his first victory.

Lessons:

Defer to experience. After sending Frederick off, Schwerin restored order in the Prussian ranks, turned the tide of battle and helped his king through a tough combat initiation.

Discretion is not always the better part of valor. Almost killed while retiring from the field, Frederick vowed never to leave his troops again—a promise he kept for the rest of his illustrious career.

Seize the initiative. After the near disaster at Mollwitz, Frederick issued a general directive: “The Prussian army always attacks.”

Learn from failure. Frederick made mistakes but proved as quick a study as his rival. “Mollwitz was my school,” he later admitted.