Out of war springs peculiarly named traditions — from “zappings” to The Brush-Off Club — humor often becomes ties that bind.

Add to that the “short snorter,” and no, we promise it has nothing to do with vodka shots nor the use of any white powder.

The term dates from the 1920s with its use reaching a climax during the Second World War. Although “short snorter” originally meant a smaller serving of alcohol, it soon referred to the signing or signer of a $1 bill. How?

“The origins of the short snorter remain uncertain,” writes the National WWII Museum, “but we do know that the practice of swapping signed dollar bills predated World War II and was initially an esoteric ritual performed by pilots. Alcohol generally followed.”

Evidence points to 1925 as the origins of the short snorter club. According to the museum, stunt aviator Jack Ashcraft failed to bring his fair share of alcohol to a post-circus barnstormer party. The following day, to assuage (or swindle) fellow aviator Clyde Pangborn, Ashcraft:

“… let Pangborn in on a sneaky scheme of his own design. ‘Gimme two bucks,’ Ashcraft demanded before his superior could admonish him. Pangborn searched his suit and forked over a dollar bill and a piece of stage money. The sly pilot signed the fake bill ‘Short Snorter No. 1,’ dated and handed it back to his boss, and pocketed the real one. ‘Now you’re a short snorter,’ Ashcraft asserted.”

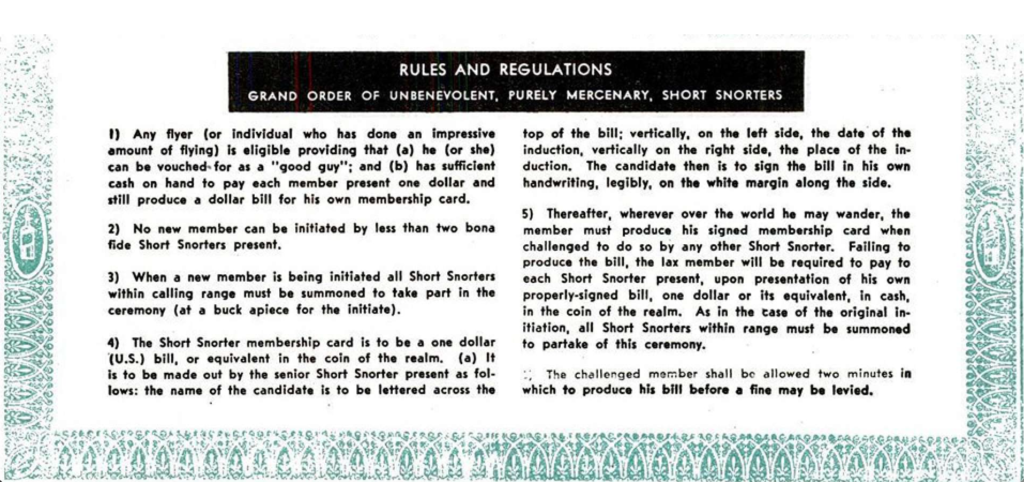

From there, the cheeky swindle spread among other aviators and was eventually dubbed the Grand Order of Unbenevolent, Purely Mercenary, Short Snorters.

Soon after, a codified set of rules and regulations were put into place, including bylaws such as: Any flier (or individual who has done an impressive amount of flying is eligible providing that (a) he (or she) can be vouched for as a “good guy”; and (b) has sufficient cash on hand to pay each member present one dollar and still produce a dollar bill for his own membership card.

As the United States was drawn into World War II, membership to the once elite club exploded, and members of the military who fought by land or sea were no longer exempted.

Writer John Steinbeck lamented the club’s swelling membership, writing in a dispatch from North Africa to the New York Herald Tribune in 1943 that “The original half of the joke has been lost. Serious and intelligent gentlemen sign one another’s bills with an absolute lack of humor.”

Short snorters became a tangible piece of the war. Once a soldier, airman, or sailor filled up their dollar bill with signatures, they would tape another one on — including whatever foreign currency happened to be available at the time.

“Short snorters told the stories of the servicemen and women, where they traveled, the battles they fought in, and the people they met along the way,” according to Atlas Obscura. “How many bills were included in each snorter was also part of the status symbol. For a long time, the longest was believed to be owned by one Captain John L. Gillen, measuring a reported 100 feet, or about 200 bills. But In 1993, a 172.5-foot short snorter came up for auction, breaking Gillen’s record. Dietrich’s short snorter fetched over $5,000 at auction in 2017.”

Famous short snorter members included Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower — whose own collection included over 90 signatures — and Winston Churchill, who had been inducted by the American general.

Others included first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and actress Marlene Dietrich, whose short snorter was signed by Ernest Hemingway and Gen. George S. Patton (who was also a member).

While membership to the Grand Order reached the upper echelons of the Allies, it also marked personal moments from a personal war.

Delbert Zane Schlemmer of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment jumped with the 82nd Airborne Division behind enemy lines in the wee hours of June 6, 1944. Fellow paratroopers subsequently signed Schlemmer’s “snorter,” as did Pierre Cotelle, the Norman farmer on whose property Schlemmer landed, according to the National WWII Museum.

And despite Steinbeck’s distaste, the short snorter has become a physical reminder from a time when war engulfed the world.