When the guns along the Western Front fell silent on Nov. 11, 1918, most of the world breathed a huge sigh of relief. The war that many had believed would last but a few months had ground on for four years, devastated much of Belgium and northwestern France, toppled Russia into revolution, dissolved the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires, killed at least 16 million people (six million of them civilians), and wounded 20 million more. At that time it was by far history’s worst conflict.

When the guns along the Western Front fell silent on Nov. 11, 1918, most of the world breathed a huge sigh of relief. The war that many had believed would last but a few months had ground on for four years, devastated much of Belgium and northwestern France, toppled Russia into revolution, dissolved the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires, killed at least 16 million people (six million of them civilians), and wounded 20 million more. At that time it was by far history’s worst conflict.

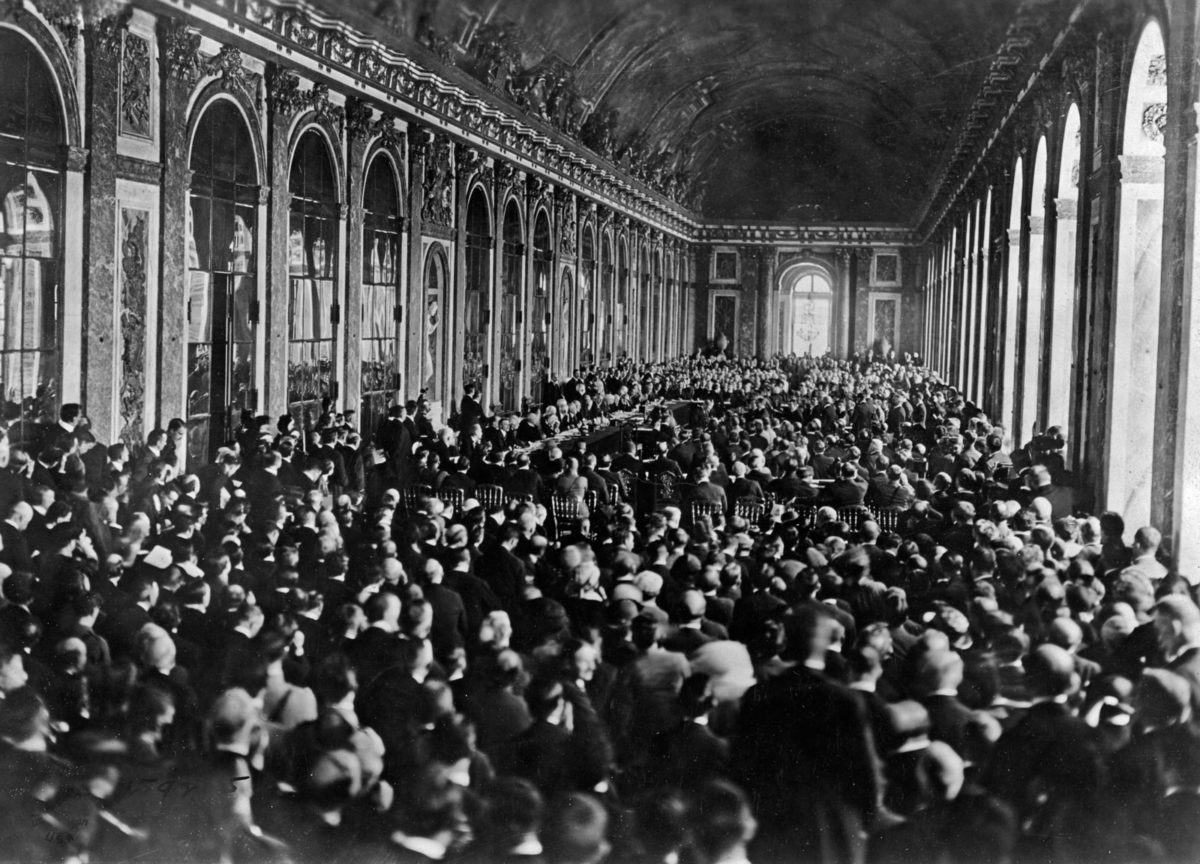

Given its scale, many hoped that the Great War would live up to British essayist H. G. Wells’s 1914 epithet: “the war that will end war.” But how to craft a peace that could achieve this lofty aim? At the very least, the negotiators who gathered in the gaudy palace at Versailles hoped to forge a settlement as durable as the 1815 Congress of Vienna. That effort had restored Europe in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars and inaugurated the “Long Peace” that spared Europe a state of general war for nearly a century.

The peacemakers failed, of course, and the Versailles settlement became, as Marshal Ferdinand Foch, supreme commander of the Allied armies, dolefully predicted, a mere “armistice for 20 years.”

But could the Treaty of Versailles have succeeded? Could a second world war have been averted? The opinion of Williamson Murray, one of today’s foremost military historians, is an emphatic no. Good counterfactuals depend on plausible “minimal rewrites” of history, otherwise they are sterile exercises devoid of meaningful insight. In Murray’s view, no minimal rewrite of the Versailles settlement is possible.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Could it have been more lenient toward germany?

At Versailles, two issues predominated. The first: what to do about Germany? Two basic responses were possible. A lenient peace based on no annexations or indemnities, as President Woodrow Wilson posited in his famous “Fourteen Points.” Or, a punitive peace that rendered Germany incapable of making mischief. A purely Wilsonian settlement was out of the question; popular opinion in Great Britain, France, and elsewhere simply would not have accepted it. Instead, Wilson threw much American diplomatic clout into the establishment of a League of Nations intended to settle disputes peacefully. This proved a quixotic venture.

France, the western great power that had sustained the brunt of German malice, was most intent on defanging German military strength (a goal it achieved), and on securing enough in reparations to offset the tremendous financial and human price it had paid. The incongruity in the second aim, as Murray notes, is that Germany could not possibly pay the massive reparations France sought without regaining its former status as Europe’s preeminent economic power. Consequently, within a few years the Allies adjusted the reparations schedule to allow for full German economic recovery.

Recommended for you

What about the Austro-hungarian empire?

The second major question: what to do about the multiethnic stew created by the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s collapse? Here a second major element in the Wilsonian formula for peace became central: self-determination. Serbian nationalism had helped trigger the Great War; now other ethnic groups’ nationalist aspirations promised to keep Europe in turmoil unless those aspirations were satisfied. For that reason, the Versailles settlement divided eastern and south central Europe into a mosaic of small nation-states such as Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and, above all, Poland.

This had three unhappy consequences. In 1914, Germany had bordered three great powers — France, Austria-Hungary and Russia — which, from a balance-of-power standpoint, stood a reasonable chance of keeping German ambitions in check. After Versailles, Germany directly faced only one great power: jaded and much-battered France. The creation of a Polish corridor to the Baltic Sea, although necessary to make a Polish state economically viable, effectively split Germany in two—an outcome the Germans understandably deemed intolerable. And the principle of self-determination conspicuously excluded Germany: in addition to other territorial losses it was explicitly denied German-speaking areas like the Sudetenland, as well as the right to unite with German-speaking Austria. Germans regarded these sanctions, with reason, as an unjust double standard.

Perhaps the best chance to resolve the Germany problem, Murray avers, was lost when the Allies, rather than fighting on, accepted Germany’s request for an armistice. Ending the war without invading Germany allowed many Germans to conclude that their country had not suffered military defeat, but rather had been “stabbed in the back” by Socialists and Jews. American general John J. Pershing is known to have advocated pushing all the way to Berlin. But the French and British never seriously considered such a course. Instead, they gratefully embraced the opportunity to end the war at once. Given the horrific losses they had already sustained, it is impossible to imagine them doing anything else.

Was Versailles always Doomed?

All in all, Murray concludes, the peacemakers gathered at Versailles were confronted with an impossible task. They could not reconcile the various stakeholders’ aspirations, the pressures of popular opinion, and the conflicting principles that haunted the conference table. The title of the essay in which Murray makes his argument is thus highly apt: “Versailles: The Peace without a Chance.”

Unlike other “what if” scenarios, in which the key lesson is that a slight change here or there could have altered the result, a counterfactual analysis of the Versailles settlement yields a strikingly different insight. It strongly suggests that a second general European war was inevitable from the moment that the Great War ended. Marshal Foch, then, was more correct than he knew. Not only did the Versailles settlement prove to be nothing more than an armistice for 20 years — it could never have been anything else.

With this column, “What If…” ends a nearly seven-year run. Look for Mark Grimsley’s new column, “Battle Films,” beginning next issue.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.