The annals of the Second World War are filled with fateful battles: the Battle of Britain, the Battle of Stalingrad, the Battle of the Bulge. But few were as significant as a battle of which few have ever heard: the “Battle of the Potomac,” where civilian and military planners wrangled over the best way to mobilize American industry in support of the war effort.

The annals of the Second World War are filled with fateful battles: the Battle of Britain, the Battle of Stalingrad, the Battle of the Bulge. But few were as significant as a battle of which few have ever heard: the “Battle of the Potomac,” where civilian and military planners wrangled over the best way to mobilize American industry in support of the war effort.

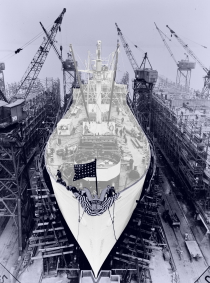

During the war, the United States functioned exactly as President Franklin D. Roosevelt promised it would: as the free world’s “Arsenal of Democracy.” Between July 1940 and September 1945, American shipyards and factories produced 2,261 major warships, 66,055 landing craft, 297,000 aircraft, 86,000 tanks, and 2 million trucks. It not only equipped its own forces but produced a quarter of all weapons used by the British Empire, as well as 427,000 trucks and 13,000 combat vehicles used by the Soviet Union. All in all, American output amounted to two-thirds of Allied military production. It exceeded that of all the Axis powers combined.

This prodigious output in so short a time is generally taken for granted. But as sociologist Gregory Hooks points out, “It was not inevitable that the United States would become the ‘arsenal of democracy’ or that the U.S. state would effectively plan the mobilization.” One need only look at the “exceptionally ineffective” American mobilization during the First World War, in which the U.S. government “had neither coordinated nor maintained control of the mobilization.” Far from materially assisting its Allies, the United States had instead equipped much of its force with planes and artillery acquired from Great Britain and France.

American military planners learned their lesson. And ironically, the Great Depression also proved of great assistance, for by triggering massive governmental intervention to contain the disaster, it gave the United States government invaluable familiarity with large-scale economic planning. Furthermore, by creating a labor surplus and an under-utilization of manufacturing capacity, the Depression eased the task of gearing up for war.

At the same time, however, in the late 1930s, through 1941, the U.S. government had to make numerous decisions about how to handle a war economy. Would it rely upon market forces or create a command economy? Would able-bodied men be required to “work or fight”; that is to say, assume jobs in military manufacturing or join the armed forces? To what extent would the country borrow funds to pay for the war? To what extent would it rely upon taxation?

The government made most of these decisions astutely, or at least adequately, and military production climbed even as policymakers fumbled to find the right solutions. Probably no number of errors could have throttled the increase in production outright. But it was still possible to commit blunders serious enough to depress the rate of expansion and delay the moment when the United States could launch decisive military operations against Italy, Japan, and above all Germany. The experience of the War Production Board (WPB) is a case in point.

Established in January 1942, the WPB was a civilian agency formed to coordinate economic mobilization for the war. It was the successor to what historian David M. Kennedy calls a “notably ramshackle, poorly articulated array of mobilization agencies with overlapping and sometimes conflicting missions.” At its helm was Donald M. Nelson, a senior vice president for Sears, Roebuck and Co., whom Roosevelt believed possessed the necessary managerial skill to get all the major stakeholders—big business, small business, labor unions, and the various military appropriations agencies—to pull together in harness. Roosevelt proved mistaken, but it required many months to figure this out.

Chief among Nelson’s opponents were the military appropriations agencies, massive organizations run by tough-minded senior officers who were considerably more skilled at political infighting than the affable, too conciliatory Nelson.

The major players in the War Department—Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Undersecretary Robert Patterson—considered Nelson a lightweight. In this they were joined by Lieutenant General Brehon B. Somervell, head of the Army Service Forces, who not only had scant regard for Nelson but regarded the entire idea of placing civilian war agencies in charge of industrial mobilization as a plot by “leftists to take over the country.”

The heart of the dispute was over who would have de facto control of war production, an urgent matter because the current system was a train wreck in the making. Production control was, of course, the very purpose of the WPB. But procurement agencies like the Army Service Forces adeptly sidestepped the board. Worse, they frequently made contracts for far more than manufacturers could produce with available materials. Manufacturers, in turn, overstated their actual needs so as to get as much of these materials as possible. The effect, Stimson observed, was that of “hungry dogs quarreling over a very inadequate bone.”

With the blessing of the War Department, in May 1942 Somervell proposed to solve the problem by placing production management in the hands of a Combined Resources Board. Although ostensibly chaired by a civilian, the board would really be run by the military and would report directly to the U.S. and British Chiefs of Staff. Nelson saw this for what it was: an attempt to neuter the WPB. He replied that the general was “basically in error.” Industrial mobilization, he insisted, “rested not with the Chiefs of Staff, but with the chiefs of production.” Somervell basically ignored him. At one point Nelson delayed a planned trip to London to meet with his British counterpart. If he left the country, Nelson told a friend, “I’m afraid they’d steal my desk before I got back.”

Poring over stacks of data, economists working for the WPB assessed the dysfunctional planning system with mounting horror. The military thought in terms of outputs such as tanks, artillery, and landing craft. The economists recognized that the real key was inputs: the amount of available strategic materials such as steel, aluminum, copper, and rubber. If the military procurement agencies and manufacturing firms determined the allocation of these materials on the basis of outputs, the United States might end up with tanks without treads, aircraft without spark plugs, warships without watertight hatches.

In September they compiled their findings into a thick report and placed it in the hands of the major planners, including Nelson and Somervell—the former reacting with a smile of vindication, the latter with a snarl of fury. That report inaugurated what became known as the Feasibility Dispute. For two weeks the rival parties had it out with one another, until at length they reached a compromise solution. The military conceded that their ambitious output objectives “ought not be far in front of estimated maximum production,” and Nelson agreed to a Controlled Materials Plan in which both civilians and soldiers would participate. Under the plan, the War Department, Navy Department, Lend-Lease Commission, and other organizations would present their requirements to the WPB. The WPB would then allocate specific quantities of strategic materials to these agencies, which in turn would distribute them among their prime contractors. In charge of this program was one of its main designers, investment banker Ferdinand Eberstadt.

Eberstadt had an authority that Nelson never quite possessed, and took charge in a way that Nelson never could. Within weeks, columnist Drew Pearson could inform his readers that “Eberstadt has more power over the life of the Nation than any one man today except the President.” He held a place “so strategic that practically no civil or military production can proceed without his approval.” More changes in the way the United States organized its vast industrial mobilization would come. But a potentially crippling defect in the process had been averted. America had won the bureaucratic Battle of the Potomac, and with it hastened victory in the military battles ahead.