Precious household goods and objets d’art disappeared after Yankees plundered the city. Some pieces were returned.

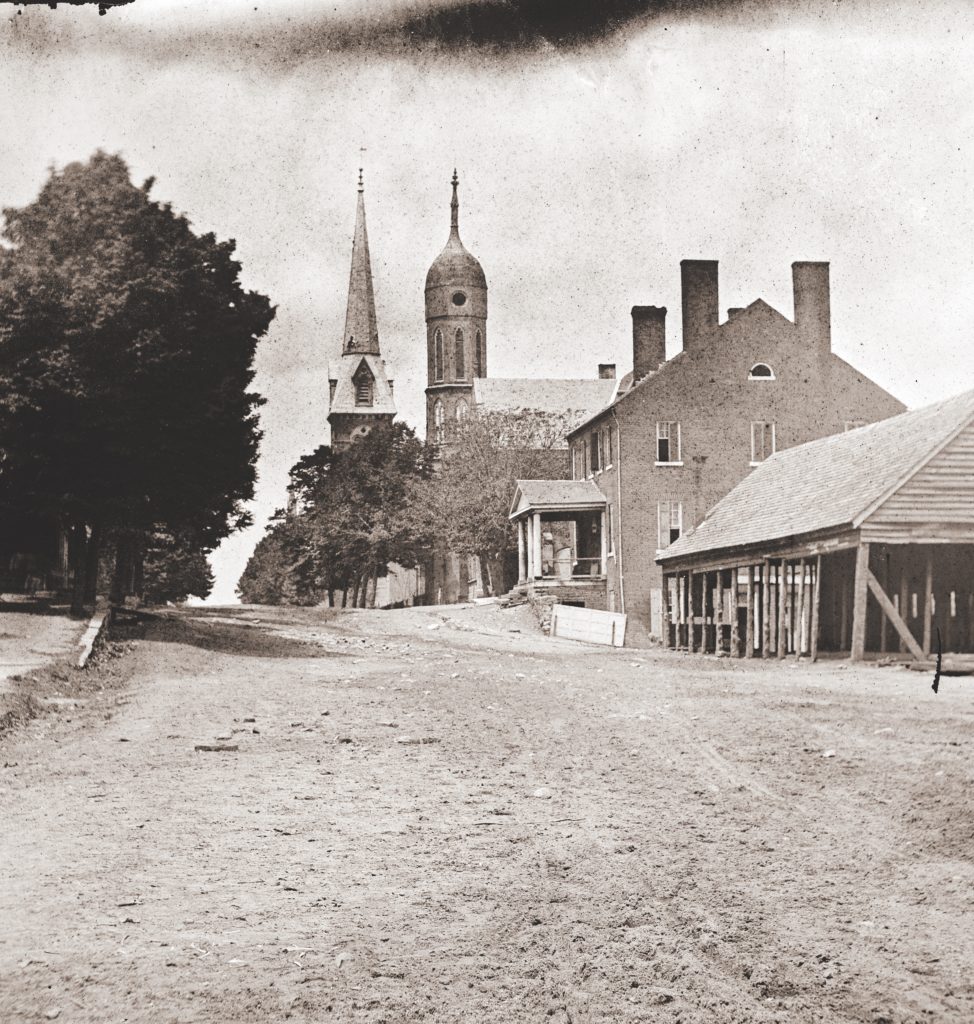

Before Fredericksburg became a vast graveyard for the Army of the Potomac, the Federals bombarded and plundered the Virginia town on the Rappahannock River. “Vandals” and “base savages,” a Southern newspaper called the Yankees, who left few private residences or businesses there unscathed December 11-15, 1862. A Mississippi regiment was so incensed by destruction wrought by “Lincoln’s abolition hordes” that soldiers donated $651 to Fredericksburg’s citizens. In Staunton, Va., two young ladies collected $850 for the town’s unfortunate sufferers.

During their occupation, Union soldiers dragged pianos from houses and absconded with silverware, rare books, paintings, and even fashionable women’s clothing. Glassware was broken and scattered. Family pictures were mutilated and destroyed. Beds and bedclothing were carried off. Dresses, men’s clothing, letters, sheet music and more were tossed into the streets or ground into mud.

“With bare-faced impudence,” a Virginia newspaper reported, a Union prisoner told how his company used looted furniture for campfires. Another POW bragged about sacking a bookstore, “tearing the books to tatters and scattering them into the streets.”

A Pennsylvania officer rationalized the looting. “This was not due to pure vandalism, although war creates the latter but to the feeling of hatred for the miserable rebels who had brought on the war and were the cause of our being there,” he wrote. The argument for plundering, the officer added, was: “Somebody will take it, and I might as well have it as the other fellow.”

Unsurprisingly, a Richmond newspaper correspondent offered a scathing assessment of the Yankees’ behavior:

“…[E]verything that could not be easily removed was most wantonly destroyed, and every portable article taken away [is] to be sent home to friends and adorn, perhaps, private collections and take conspicuous positions among parlor ornaments in Yankee households as reminders of the achievements of the Grand Army in its fourth attempt to take Richmond.”

Indeed, some of the loot was sent north by Federals. Here are stories of valuables filched from Fredericksburg…and where they may be found today.

No Sanctity

Not even Fredericksburg’s churches were immune from damage and looting. St. George’s Episcopal on Princess Anne Street was struck by at least two dozen rounds during the Union bombardment on December 11. Yankees also stole from a hiding place in the rafters a four-piece silver communion set—a flagon, two chalices, and a paten (communion plate). The holy items were a gift to the church in 1827.

Before the Federal army retreated across the Rappahannock River, Lieutenant Frederick L. Hitchcock of the 132nd Pennsylvania Infantry spotted another Federal soldier—a “scamp,” he called him—carrying off the flagon. “Fortunately, he did not belong to our regiment,” Hitchcock recalled. “Our chaplain took it from him and had it strapped to his saddle-bag. His purpose was to preserve it for its owner if the time should come that it could be returned. But in the meantime its presence attached to his saddle made him the butt of any amount of raillery from both officers and men.”

At an unknown date, one of the chalices was retrieved from a Federal soldier in the street by St. George’s sexton. In 1866, the church received the flagon in the mail. The return address: “New York Police Department.” In 1869, the paten was discovered in possession of a New York man, reportedly a “candidate for high public office.” On behalf of St. George’s, a rector in a church in New York offered to purchase it, but the man refused to sell. Then negotiations with St. George’s, according to a 20th-century Virginia newspaper account, became “rather heated.”

When the plate possessor was threatened with exposure in New York newspapers, he reluctantly agreed to return it. He planned to do it in person. Better not, St. George’s parson told him, because the Yankee’s safety could not be guaranteed.

Through less tedious negotiations, the other communion chalice was returned nearly 69 years after it was swiped. In April 1931, a Massachusetts woman alerted St. George’s officials she had the prized relic. An inscription on the chalice pointed her to the church: “Presented by John Gray, Esq., to the Episcopal Church St. George’s Parish Fredericksburg, Virginia A.D. 1827.”

“I understand it was found in the rafters of your church during some war and was found later by a distant relative of mine and eventually got into my hands.” Lillian A. Thayer, daughter of a Civil War veteran, wrote in a letter to St. George’s. “I think the world of it, but I’m writing to find out that if your church is still in existence, would the head of the church care enough about it to offer me a reward for it?”

A widow with two children, Thayer said she had been offered $80 for the chalice by a friend who collected antiques. She would, though, accept $50 from the church for it because, “I would rather you have it of course.”

In a sternly worded response, the Rev. Dudley Boogher of St. George’s wrote:

“The Holy Communion service, of which this cup was a part, was stolen by Federal soldiers from a hiding place in the rafters of St. George’s Church during the siege of Fredericksburg in the Civil War. It of course is still the property of the church as the inscription which you state is engraved on it clearly indicates. Of course, this piece could be secured through process of law. To secure it that way would not be pleasing for any of us.”

The church agreed to pay Thayer $50, “a very liberal reward,” Boogher noted. St. George’s received the chalice from Thayer in the mail that June.

“It certainly is a great sacrifice to me to give it up,” the widow wrote to Boogher, “especially for such a small amount when I have been the person to have taken such good care of it. However, I hope the church will no doubt appreciate it after its absence of so many long years.”

Even in the 20th century, the communion set was a target of thieves. It was stolen in 1980, but the set was found shortly afterward in a nearby alley. About a decade later, it was stolen by someone who broke into the church. A reward was offered, and the set was eventually recovered in the home of a Virginia man.

Now usually kept under lock and key, the communion set remains in use at Sunday services at St. George’s.

Brothers in Arms

Fredericksburg’s Masonic Lodge No. 4 is steeped in history. During the Revolutionary War, George Washington was among its 95 Masonic brothers who served in the Continental Army. The first president, whose boyhood home was a ferry ride across the Rappahannock from town, took his first Masonic oath on a Bible in Fredericksburg in 1752.

During their occupation, Yankees plundered the red-brick Masonic headquarters on Princess Anne Street. Although the Washington Bible escaped their clutches—it was stashed away in Danville, Va.—the Masons’ records and other valuables were stolen or destroyed. Among the treasures that disappeared was a Masonic “jewel,” a small ornament of crossed silver keys that belonged to the lodge’s treasurer.

In April 1884, the ornament was returned to Lodge No. 4 by William Lines, a Union veteran who became a Mason after the war. At Fredericksburg, he served as a sergeant in Battery C of the 5th U.S. Artillery. The Pennsylvanian had hoped to return the loot in 1872, but he received no reply from the Fredericksburg postmaster about his query regarding its ownership. Another attempt by Lines at an unknown date also was fruitless.

“A few days previous to the battle,” Lines explained in the letter with the jewel, “some recruits joined us, but as they had not been drilled, were left in the rear at the battle, and during the time that Fredericksburg was in our hands, they took part in the looting of the town.” One of the looters, Lines said, gave the jewel to him.

“Should this prove to be one of No. 4’s jewels, and the lodge’s minutes show its return by me,” Lines added, “please have the minutes so worded as to show the facts as to how it came in my possession. For obvious reasons, I do not want to go upon record as a pillager of private property.”

The Masons’ secretary, according to a contemporaneous newspaper account, sent a “most fraternal reply with the sincere thanks of the lodge.” In 1894, six months before his death, Lines visited with the Masons in Fredericksburg, where he was treated with the “highest consideration.”

The Masons display the jewel in their museum at Lodge No. 4.

European finery

When a newspaper correspondent entered Douglas Hamilton Gordon’s house on Princess Anne Street, he saw marauding Yankees “divesting themselves with rich dresses found in the wardrobes.” Some tried on bonnets, “surveying themselves before mirrors,” which were later pitched out the windows and “smashed to pieces.”

Gordon, whose personal estate was valued at $560,000 in 1860 (about $17 million today), was the richest man in the Fredericksburg region. But his house, seriously damaged by Union artillery, was fairly plain.

Besides the destruction caused by Union soldiers, an ornate statue of a knight was stolen from Gordon’s vast art collection.

The Gordons had procured the impressive piece—a 33-inch bronze replica of a European statue—decades earlier in Italy.

Nearly a year after the battle, Anne Thomas, Mrs. Gordon’s sister-in-law, overheard a Federal soldier talking about the statue in Baltimore, where troops were camped near her home. According to Thomas, the soldier said it was the best thing he saw plundered in Fredericksburg. Seeking the statue’s return, she contacted President Abraham Lincoln’s physician, Robert King Stone.

An acquaintance of Stone’s in the War Department told him the statue was traced to 69th Pennsylvania Lt. Col. Joshua T. Owens, who had purchased the plunder from another Union soldier. “The Penna Colonel said he valued it, at $2000, on account of its intrinsic value, as a piece of art & besides, because it was so peculiarly obtained!” Stone quoted the official in a letter to Thomas. The statue eventually ended up at the War Department in Washington, D.C. When Owens attempted to claim it there, an official declined his request. The officer took his case to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who, apparently flabbergasted, considered taking away Owens’ commission.

Stanton issued an order for the return of the bronze, its marble pedestal missing, to Mrs. Thomas. In 1992, the statue was donated to the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond, where it may be viewed today. Douglas Gordon’s house on Princess Anne Street still stands; it has been used by various businesses over the past several decades.

Dance With the Devil

In 1862, 38-year-old William Warren, a well-to-do merchant, lived with his family at the corner of Amelia and Caroline streets, a little more than a city block from the tanning yard he operated on the Rappahannock River. His house was severely damaged during the Federals’ bombardment and looted by Union soldiers. An 1838 edition of Dialogues of Devils, which chronicled the “many vices that abound in the civil and religious world,” was among the books stolen from Warren’s library.

Dialogues ended up with Cyrus Snow Crain, a 37-year-old private in Company D of the 44th New York. “Taken from the deserted house of a wealthy citizen of Fredericksburg, Va. where books [and] furniture were scattered about in profusion,” he wrote on a blank page inside the book. “Preserved as a memento of the occupancy of that city by our troops Dec. 13th, 14th, 15th 1862.” Crain kept Dialogues for the remainder of his wartime service.

For the well-educated Warren, who also was involved in the cotton, iron, and grocery businesses, the war brought financial ruin. His personal estate, according to the 1860 census, was worth $12,000—an impressive sum at the time.

At an unknown date, Warren moved with his wife, Mary, to Richmond, “where he soon won recognition as a business man of fine abilities and sterling worth.” In 1870, he went to work for a bank as a bookkeeper and discount teller, among other roles, positions that spanned decades. It was a giant step removed from his previous station in life.

After his wife’s death in 1874, Warren moved in with a daughter and son-in-law in Richmond. There, on November 22, 1900, he was struck by a dray at Tenth and Broad streets while on his way home from work. Three days later, he died from his injuries at his daughter’s house. The 74-year-old Virginian was buried in his hometown of Fredericksburg.

“Our brother was a man of aesthetic nature and refined tastes, with a decided literary bent, which he occasionally indulged in excursions into the field of poetry, with no mean success,” a newspaper obituary noted about Warren.

For Crain, the Civil War dragged on. He spent part of the winter of 1863 at the 5th Corps post hospital at Windmill Point, the largest military hospital in the Fredericksburg area. On a blank page in the back of Dialogues, Crain even wrote scathing reviews of Windmill Point:

“These scribblings were offered to while [sic] away time while in the hospital at Windmill Point, Va., a bleak promontory on the Virginia side of the Potomac, a few miles below Acquia [sic] Creek. The sick and wounded were hastily taken here before the necessary preparations were completed; as consequence many died [and] others suffered much.”

And on another page:

“Would…the people north know how the government treated its sick soldiers at Windmill Point there would be a storm.”

Crain became regimental chaplain in March 1863 and was discharged from the Army a year later.

In battered condition, Dialogues of Devils may be found in Rockville, Conn., in the New England Civil War Museum, a former Grand Army of the Republic hall. How it got there is a mystery.

Crisis of Conscience

Nearly 23 years after he served in the Union Army at Fredericksburg, Thomas Burke—“a man of warm heart and unquestioned courage”—died of pneumonia at a hospital in Hartford, Conn. At the end of his life, the man renowned for his escapes from Confederate POW camps suffered from financial hardship.

“He had not the business turn that would give him success,” the Hartford Courant reported in the 50-year-old veteran’s front-page obituary in April 1885, “and he saw hard days which he took quietly and without complaint.” Burke, whose wife had perished in a boarding house fire 13 years earlier, was buried with military honors.

A frame-maker when he enlisted in August 1862, Burke apparently had a good eye for fine art. On the walls of his residence in Hartford, the Courant noted he had “works that another man would have sold easily and at high prices, but very often remained with him some time and then went back to their former owners.”

During the war, Burke added at least one painting to his art collection: a beautiful oil painting titled “The Saviour at the Garden of Gethsemane.” It was looted from the house of Juliet Neale, a 62-year-old divorcée and one of Fredericksburg’s leading citizens. The painting was given to her by a “distinguished French nobleman.” The soldier who made off with it was none other than Burke himself—a man who, according to his obituary, was known for his “ample and spontaneous” charity. (Neale’s house on Caroline Street, used as a Federal hospital, still stands.)

Burke’s wartime service was full of hardship and derring-do: On September 17, 1862, he escaped the bloodbath at Antietam, the regiment’s first battle of the war, without physical injury. At Fredericksburg, the 16th Connecticut was held in reserve, seeing little action. Captured with most of the rest of the regiment at Plymouth, N.C., on April 20, 1864, he spent six months in various Confederate prisons.

As a prisoner, Burke attempted two breakouts. The second one, in November 1864, succeeded, as he and seven others escaped “with only rags to cover them, and nothing for their journey” from a stockade in Columbia, S.C. They eventually made their way to the Atlantic Ocean, where they were rescued by a Union blockader. Burke and his fellow escapees were given new uniforms—their “tattered, vermin rags were thrown into the sea”—and furloughs to visit home.

Perhaps it was during his furlough that Burke admired his ill-gotten goods: the painting from Neale’s house. It’s unknown how the artwork reached Connecticut. Burke had the painting in his possession until 1880, when he sold it or gave it to Charles H. Owen, who had served as a major in the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery.

Early in the 20th century, Owen decided to return the purloined painting to its rightful owner. In a front-page story under the headline “Relic of the War” on November 26, 1901, the Courant wrote about Owen’s effort:

“Correspondence with Fredericksburg has revealed that the painting was taken from the home of Mrs. Juliet A. Neale, who had bequeathed the house and its contents to her niece, Mrs. H. Mcd. Martin, who is living. Mrs. Martin remembers the picture well as it hung in the house of her aunt.”

The painting had been “obtained” by Burke in Fredericksburg during the war, according to the Courant, which added that “for a time [the painting] was mislaid and recently it was recovered.” A day after the Hartford newspaper’s report, the Richmond Dispatch picked up the story, describing the painting as “valuable” and a “beautiful picture.”

Days later, “The Saviour at the Garden of Gethsemane,” albeit damaged, finally was returned to Neale’s heir more than 39 years after it was stolen. “Before it came into my hands it had been cut from the frame, rolled tight and cracked,” Owen wrote in a letter to Neale’s niece. “It has been oiled several times to preserve it, but experts say it can never be restored to its original appearance.”

Sadly, Neale’s painting again is missing. While aware of the long-ago media coverage of its return to Virginia, Neale’s historically minded descendants in Fredericksburg are unaware of its whereabouts.

John Banks, an America’s Civil War contributor based in Nashville, Tenn., is the author of Connecticut Yankees at Antietam and Hidden History of Connecticut Union Soldiers. This story appeared in the March 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.